Grooves That Tell A Different Story

Toothpick habits were long presumed to explain the grooves, but new analysis of ancient dental marks challenges that idea, pointing instead to instinctive behavior deeply rooted in human ancestry rather than to early attempts at dental care.

Researchers Challenge Century-Old Toothpick Theory

The so-called “toothpick habit” has long been hailed as evidence of early human hygiene. But new research challenges that idea. Those familiar grooves on ancient teeth, once linked to primitive cleaning tools, might instead come from something far simpler—and entirely natural.

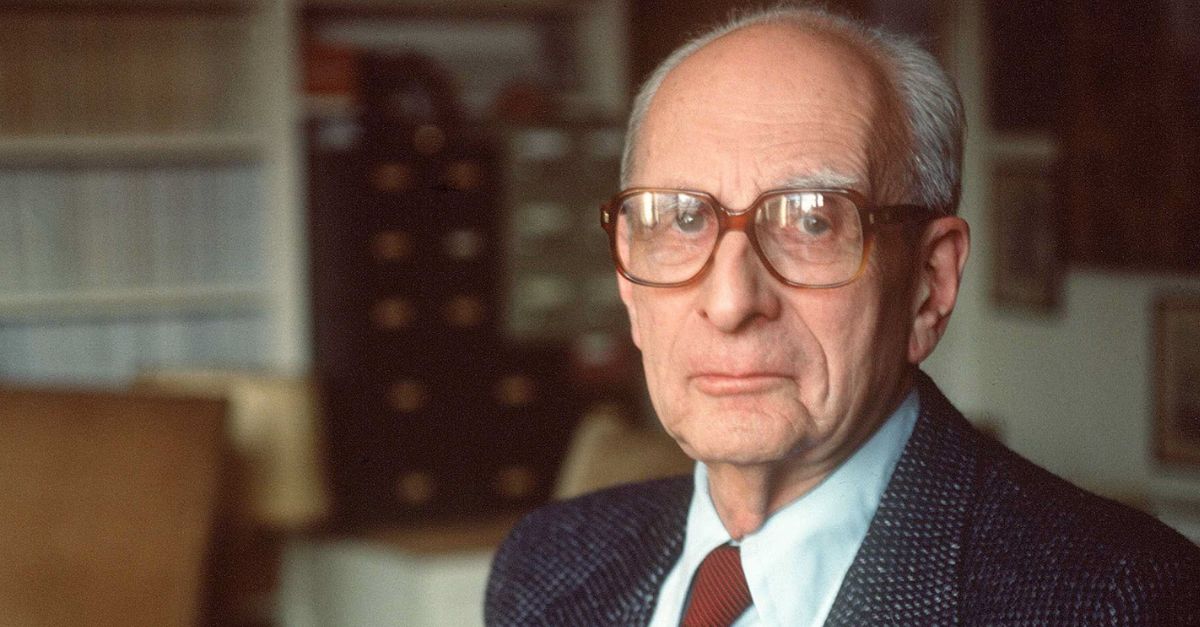

Prof. Israel Hershkovitz, Tel Aviv University, Wikimedia Commons

Prof. Israel Hershkovitz, Tel Aviv University, Wikimedia Commons

Study Examines 531 Teeth From 27 Primate Species

Across fossil and modern collections, 531 teeth from 27 primate species were examined to trace those distinctive marks. The comparison aimed to uncover whether the same patterns seen in early human fossils appeared among our primate relatives.

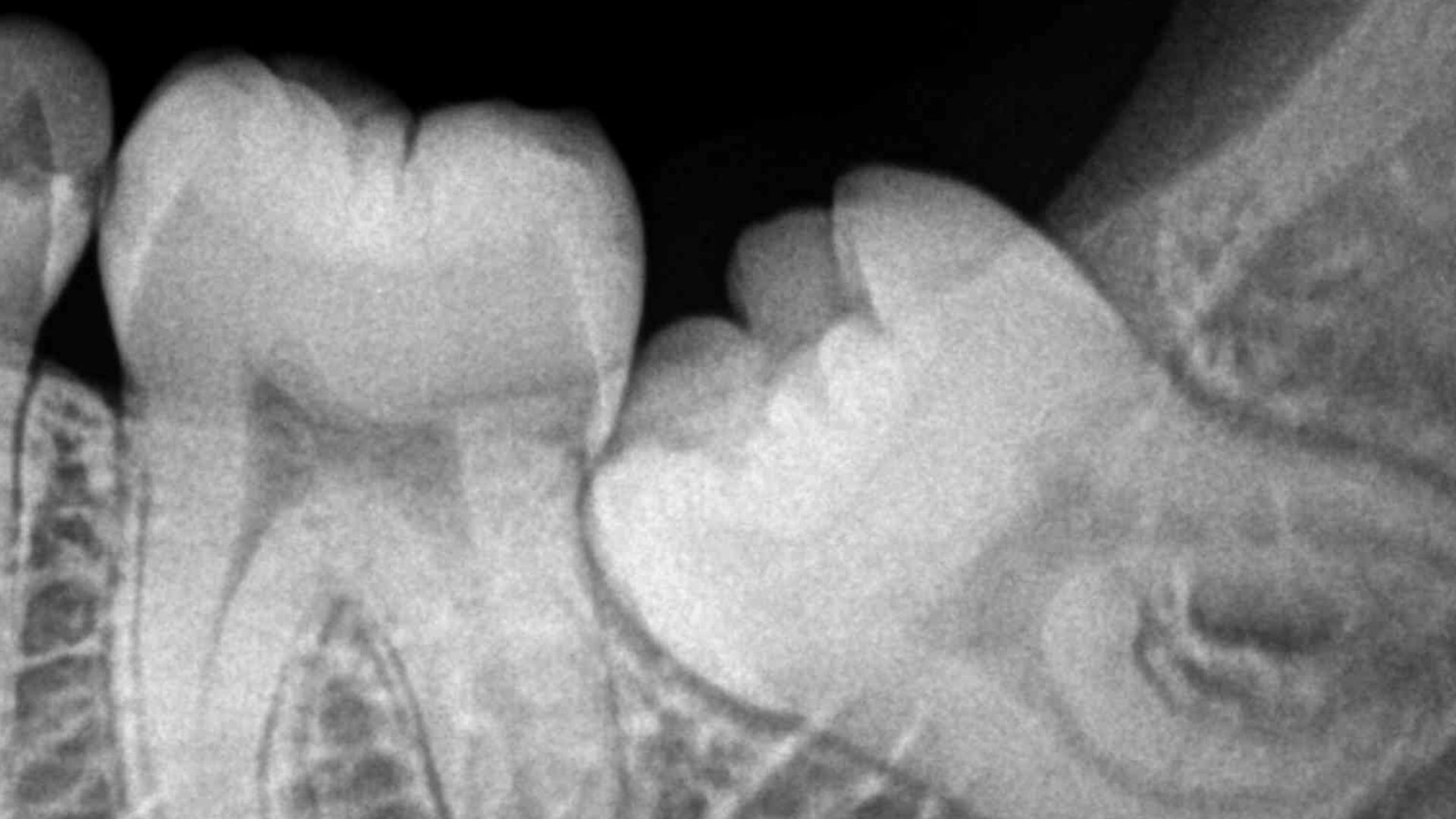

Challiyan at Malayalam Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Challiyan at Malayalam Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Grooves Found In Wild Orangutan Fossils

Among the surprises were deep grooves etched into wild orangutan teeth. These apes never craft tools, so another cause was likely at work. Daily chewing and fibrous plants, not toothpicks, may have slowly carved the lines into their enamel.

Tim Sackton from Somerville, MA, Wikimedia Commons

Tim Sackton from Somerville, MA, Wikimedia Commons

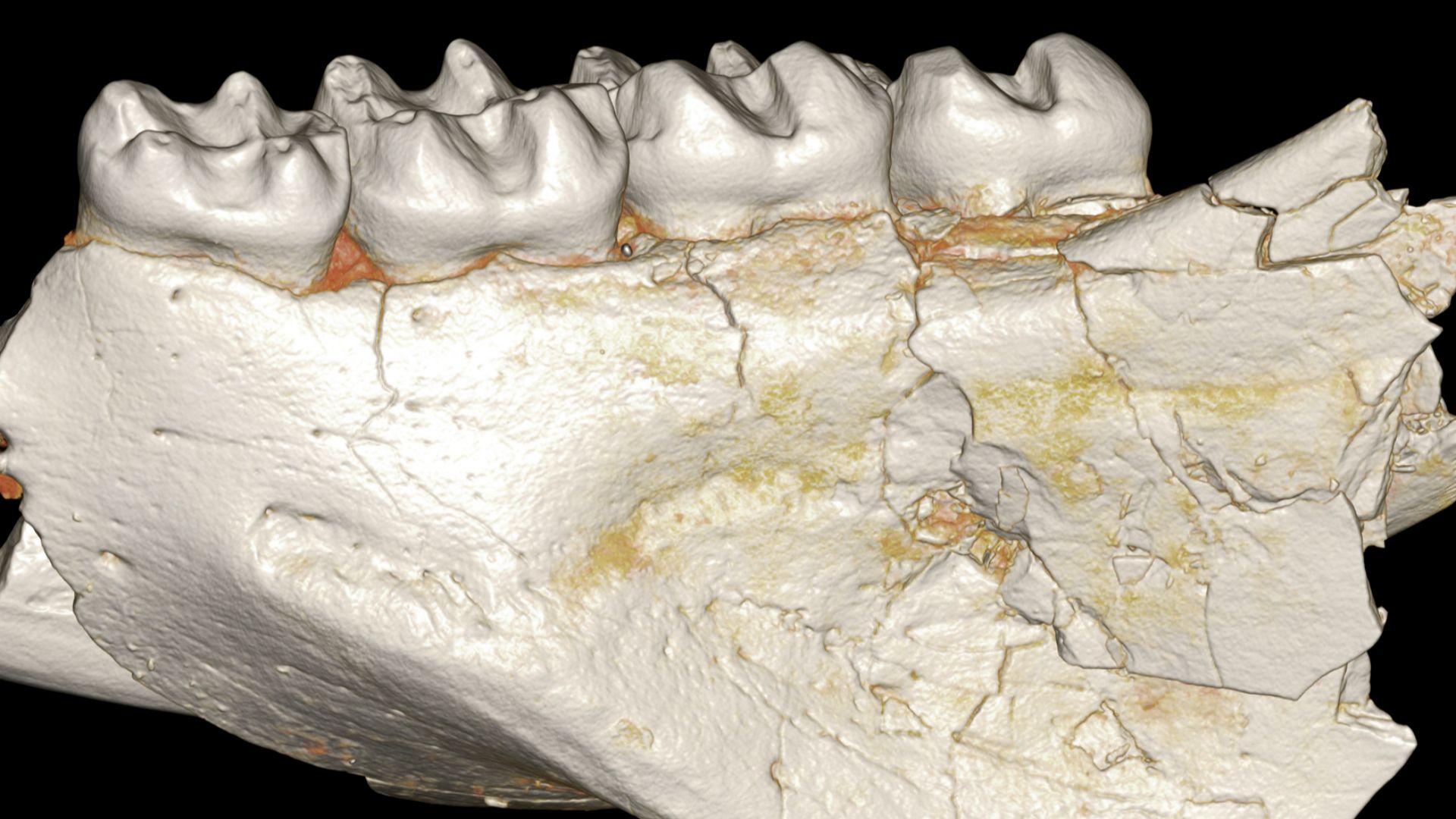

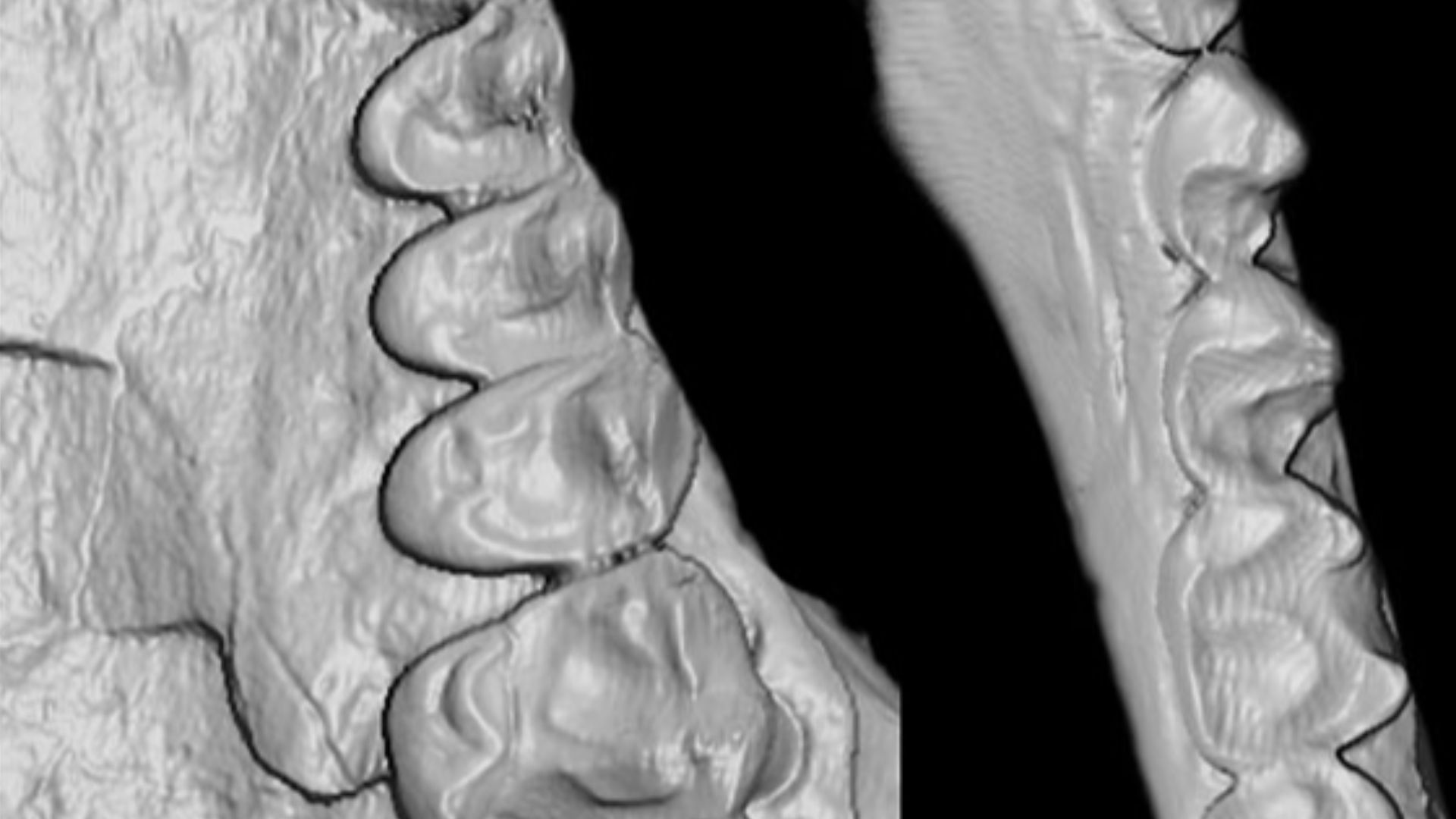

Scientists Use 3D Scanners To Analyze Dental Marks

High-resolution 3D scans captured the angles and depths of each groove in detail. The digital models revealed uncanny similarities between orangutan marks and those once labeled as toothpick wear in human fossils—evidence that questioned decades of assumptions.

Hesham M. Sallam and Erik R. Seiffert, Wikimedia Commons

Hesham M. Sallam and Erik R. Seiffert, Wikimedia Commons

Only 4% Of Primates Show Similar Lesions

Out of hundreds of samples, only about 4% displayed matching dental grooves. That rarity raised a new question: how frequently could such marks appear in nature without any human tools involved?

Amaury Laporte, Wikimedia Commons

Amaury Laporte, Wikimedia Commons

Acidic Fruits May Explain Mysterious Dental Patterns

Enamel softens when exposed to acidic fruit, something many primates eat daily. Repeated contact might have made their teeth more prone to grooves, imitating the effects once blamed on toothpicks but rooted in diet instead of deliberate action.

Natural Chewing Could Produce Toothpick-Like Grooves

Experiments simulating chewing showed that hard seeds, fibrous stems, and gritty soil can leave grooves nearly identical to supposed “toothpick marks”. The findings fit the evidence better than the idea of early humans wielding cleaning tools.

Toby Hudson, Wikimedia Commons

Toby Hudson, Wikimedia Commons

Swallowed Grit May Leave Misleading Marks

Tiny grains swallowed with unwashed roots or soil-coated plants grind against enamel and leave faint scratches. What appears to be deliberate tool use might simply be the residue of meals eaten straight from the ground.

User:Thirunavukkarasye-Raveendran, Wikimedia Commons

User:Thirunavukkarasye-Raveendran, Wikimedia Commons

Vegetation Stripping Behaviors Create Distinctive Scratches

When chimpanzees or baboons strip bark with their teeth, they leave fine, directional scratches much like early “toothpick” marks. Every day feeding behavior, repeated over years, can easily resemble the deliberate work of tools.

Carine06 from UK, Wikimedia Commons

Carine06 from UK, Wikimedia Commons

Cultural Behavior Assumptions Come Under Scrutiny

Archaeologists once viewed these grooves as signs of cultural behavior, as a symbol of intelligence and self-care. Now the evidence suggests something more biological, a reminder that instinctive actions often blur the line between survival and culture.

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument staff (National Park Service), Wikimedia Commons

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument staff (National Park Service), Wikimedia Commons

Modern Primates Do Not Pick Their Teeth

Wild primates clean their mouths with tongues or fingers, not sticks. The observation strengthens the case for natural wear, showing that chewing motions—not grooming habits—could explain the grooves that puzzled experts for generations.

Homo Naledi Debate Mirrors New Tooth Findings

The discussion echoes the debate surrounding “Homo Naledi” fossils, where natural markings were once mistaken for tool use. These parallels remind researchers how easy it is to read intention into what might simply be wear and time.

Patrick Randolph-Quinney, Wikimedia Commons

Patrick Randolph-Quinney, Wikimedia Commons

Abrasive Foods Create Similar Wear Patterns

Roots, bark, and coarse grains grind against teeth just as tools might. Over years of chewing, those materials carve shallow notches near the gumline—patterns that once seemed cultural but may simply record ancient meals.

Evolutionary Dentistry Emerges As New Research Field

From these debates, a new field is taking shape. Evolutionary dentistry merges fossil analysis with modern imaging to study how the environment and biology left their marks long before toothbrushes existed.

Abfraction Lesions Absent In All Wild Primates

The wild primates’s teeth lacked wedge-shaped lesions commonly seen in modern humans. That absence points to differences in lifestyle and stress, hinting that some of our dental problems are recent, not inherited.

Alain Houle (Harvard University), Wikimedia Commons

Alain Houle (Harvard University), Wikimedia Commons

V-Shaped Gumline Notches Remain Uniquely Human

The deep V-shaped notches along the gumline appear only in human remains. Scientists think they’re connected to how our jaws move and how tightly we bite, showing subtle anatomical differences that separate us from our primate cousins.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Forceful Brushing Linked To Modern Dental Problems

Dentists trace similar grooves today to aggressive brushing. Enamel wears away and leaves marks that mirror ancient ones. It’s a curious symmetry where both our ancestors and we leave patterns that tell stories, though for entirely different reasons.

Processed Diets Cause Contemporary Tooth Damage

Soft, processed foods now dominate human diets, yet they bring new problems. Sugars and acids erode enamel faster than tough, fibrous meals ever did. The shift reveals how comfort, rather than hardship, reshapes our teeth.

Misaligned Teeth Rare In Non-Human Primates

Crooked or crowded teeth are uncommon in wild primates, whose tougher diets required constant chewing that kept their jaws broad and well-balanced. As humans softened their food over many generations, jaw structure narrowed, gradually reshaping the way modern faces and smiles developed.

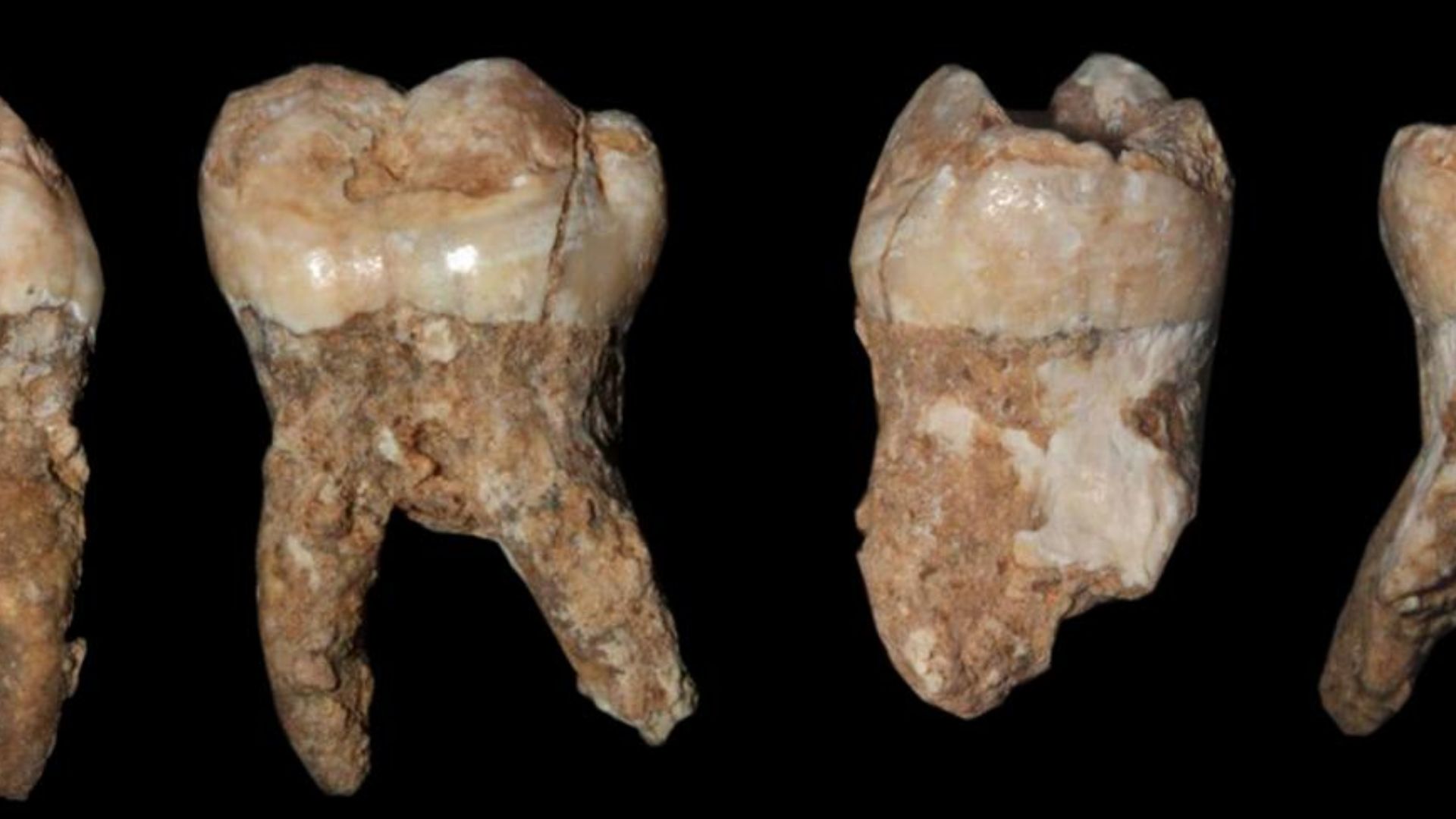

Perry et al., Wikimedia Commons

Perry et al., Wikimedia Commons

Researchers Warn Against Human-Centric Conclusions

Caution remains essential. Viewing fossils only through a human lens risks missing nature’s broader design. Sometimes, what seems intentional may simply be biology at work: a shared pattern, not a message.

U.S. Navy photo by Chief Photographer’s Mate Eric A. Clement., Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Navy photo by Chief Photographer’s Mate Eric A. Clement., Wikimedia Commons

Study Published In American Journal Of Biological Anthropology

The findings, published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology, sparked lively discussion. The evidence invited experts to reconsider daily chewing as a universal behavior that left its mark long before humans understood what it meant.

National Institute of Standards and Technology, Wikimedia Commons

National Institute of Standards and Technology, Wikimedia Commons

Two-Million-Year-Old Fossils Reinterpreted

Some of the oldest fossils once hailed as proof of dental hygiene are being reexamined. Those two-million-year-old grooves likely record ordinary chewing rather than deliberate care, a reinterpretation that reshapes what we thought we knew about our ancestors.

Neanderthal Dental Evidence Requires Fresh Analysis

Similar markings found on Neanderthal fossils are also being reanalyzed. What once seemed to confirm tool use may instead show natural wear. The fossils continue to challenge assumptions about how intelligence and instinct intertwine.

Jakub Hałun, Wikimedia Commons

Jakub Hałun, Wikimedia Commons

Tool Use Claims Need Comparative Primate Data

More comparisons across species are needed to separate deliberate behavior from basic biology. Only with that broader context can future discoveries avoid mistaking survival marks for the earliest signs of culture and better clarify how those patterns first emerged.

Cornelia Schrauf, Josep Call,Koki Fuwa and Satoshi Hirata, Wikimedia Commons

Cornelia Schrauf, Josep Call,Koki Fuwa and Satoshi Hirata, Wikimedia Commons

Cultural Explanations Require Cross-Species Verification

Before claiming culture, scientists emphasize comparison. Shared biology can produce similar marks, reminding us that intelligence isn’t the only force shaping the record of the past.