More Than Just Ancient Walls

Long before modern engineering, Pueblo builders crafted something remarkable. In a remote canyon, they raised a vast complex that still echoes with intelligence and purpose.

Pueblo Bonito Still Holds Over 400 Rooms After A Millennium

When early explorers first saw its stone outlines, they didn't expect most of it to be still standing. But Pueblo Bonito endures. Of the nearly 800 rooms once built, over 400 remain structurally visible today, a millennium after construction began around 828 CE.

Lewis H. Morgan, Wikimedia Commons

Lewis H. Morgan, Wikimedia Commons

Pueblo Bonito Still Holds Over 400 Rooms After A Millennium (Cont.)

Many of the preserved rooms retain original floor plans and wall heights. Their condition allows archaeologists to trace building phases across centuries. Stratified masonry layers and ceiling remnants confirm that these rooms were part of a larger, evolving complex that adapted as it grew.

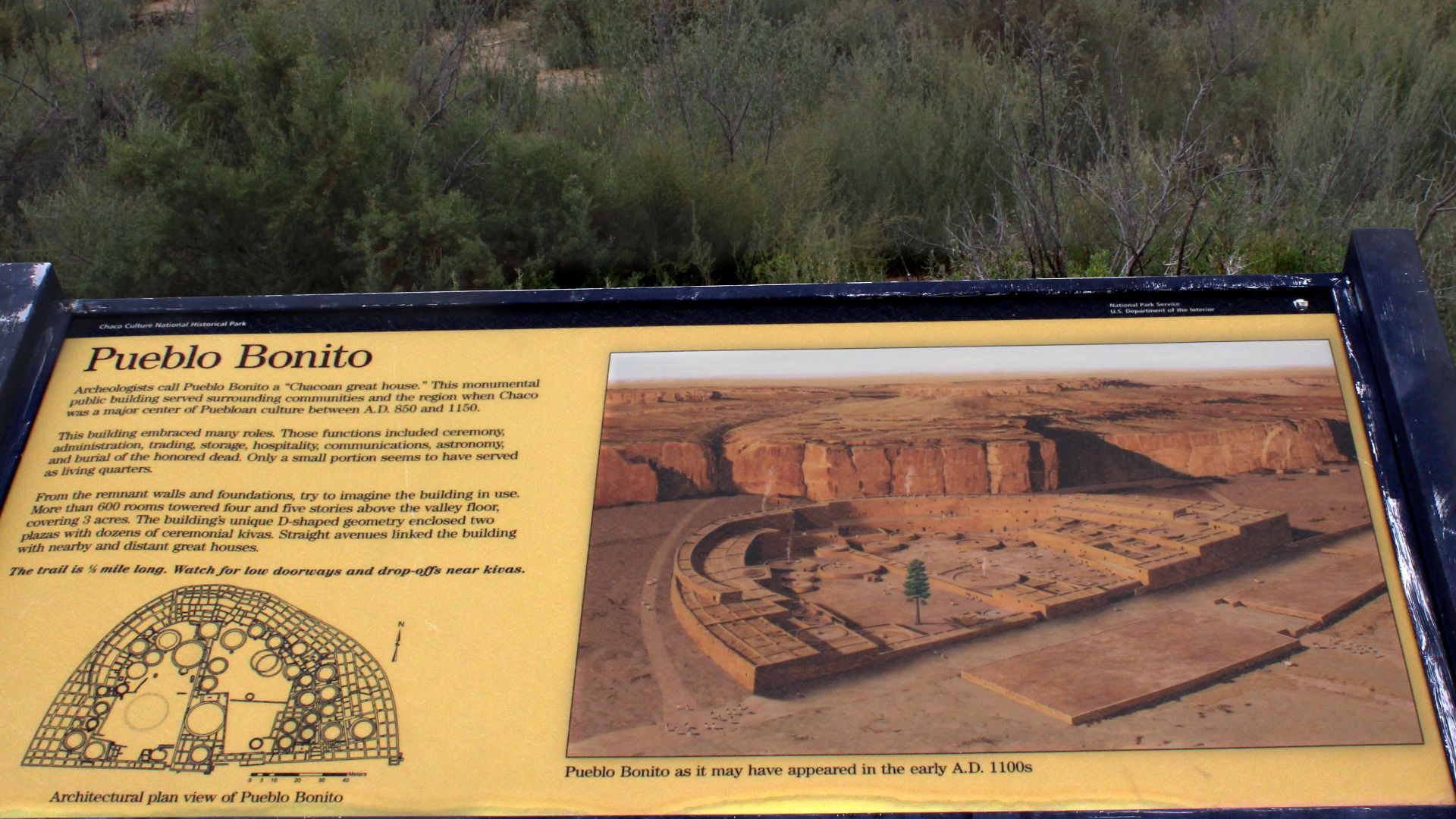

An Urban Scale Complex Built Entirely By Hand

Without metal tools or wheeled carts, ancestral Puebloans shaped an urban-scale compound. Pueblo Bonito sprawls across three acres and contains dozens of plazas and dwellings. It was the largest building in North America until the mid-1800s, entirely quarried and stacked by hand.

An Urban Scale Complex Built Entirely By Hand (Cont.)

Archaeologists estimate that Pueblo Bonito required over 30,000 man-days of labor to complete. Construction involved transporting an estimated 200,000 pieces of sandstone and hundreds of pine beams. Its scale and labor demands suggest centralized coordination and long-term planning that spanned multiple generations.

Its Stone Walls Were Engineered To Last

These walls weren't improvised. Builders layered sandstone using a core-and-veneer masonry system, where inner rubble fill was sandwiched between carefully placed outer slabs, and many walls reached three feet thick. This durable method helped the structure resist centuries of wind and time.

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

The D-Shaped Layout Served A Purpose, Not Just Aesthetics

The massive D-shape of Pueblo Bonito isn't merely a design flourish. Its curvature aligns ceremonial plazas at the open end, while the straight wall anchors multiple room tiers and great kivas. Archaeologists believe that the layout strikes a balance between ritual importance and structural function.

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Room Tiers Rose Up To Five Stories Tall

Some sections of Pueblo Bonito rose well beyond a single level, and these became vertical marvels. Excavations revealed stacked rooms built up to five stories high, which were supported by internal buttressing and massive wooden beams. Such vertical scale is rare among ancient sites on the continent.

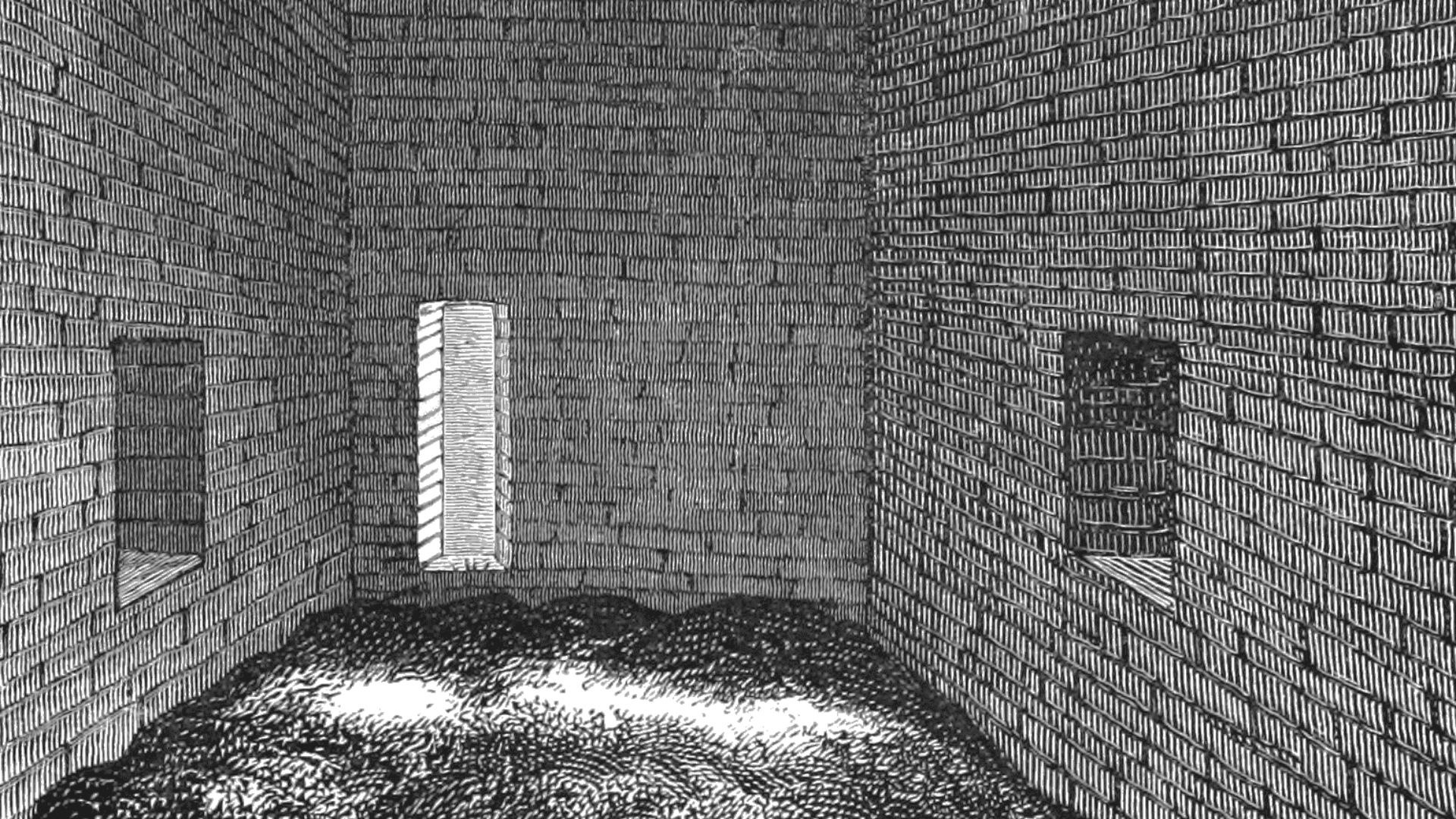

Interior Corridors Were Precisely Aligned

Straight lines cut through complexity, and the builders of Pueblo Bonito oriented interior walls and corridors along true cardinal directions. This alignment, which runs north-south and east-west, was not decorative. It guided daily movement and possibly mirrored celestial events in their worldview.

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Massive Wooden Beams Span Ceilings Without Mortar

Above many rooms, enormous wooden vigas still stretch across space. These beams, made from ponderosa pine and spruce, were cut with stone tools and placed precisely into sandstone sockets. There were no nails or cement; just gravity and expert fit held them in place.

Steven C. Price, Wikimedia Commons

Steven C. Price, Wikimedia Commons

Kivas Were Built Below Ground For Specific Ceremonial Use

Subterranean and circular kivas were ceremonial chambers built below ground. At Pueblo Bonito, over 30 have been identified, each with a fire pit and ventilation shaft. These spaces likely supported rituals linked to cosmology and the seasonal rhythms of Chacoan life.

Karen Blaha from Charlottesville, VA, Wikimedia Commons

Karen Blaha from Charlottesville, VA, Wikimedia Commons

Kivas Were Built Below Ground For Specific Ceremonial Use (Cont.)

Many kivas included a sipapu—a small hole in the floor symbolizing emergence from the underworld. Bench seating ran along the interior, and rooftops featured entry points accessed by a ladder. Their standardized design suggests shared ceremonial practices across multiple structures within the Pueblo Bonito complex.

SkybirdForever, Wikimedia Commons

SkybirdForever, Wikimedia Commons

Courtyards Enabled Shared Gathering Without Inner Conflicts

Unlike residential areas, the courtyards weren't private. These open plazas acted as gathering points, perhaps for dance or communal feasts. Their central location and separation from living spaces suggest they were designed to bring people together without disrupting household privacy.

John Wiley User:Jw4nvc - Santa Barbara, California, Wikimedia Commons

John Wiley User:Jw4nvc - Santa Barbara, California, Wikimedia Commons

Builders Used Stone Tools Without Wheels Or Metal

The people who built Pueblo Bonito had no chisels or carts. Instead, they shaped stone using hammerstones and carried materials on foot. Axes made of harder rock helped fell trees more easily. Every beam and doorway reflects a labor-intensive, low-tech mastery.

My tools - Uncle_B, Wikimedia Commons

My tools - Uncle_B, Wikimedia Commons

Sandstone Was Chiseled From Nearby Cliffs

Sandstone slabs were trimmed with stone tools and stacked layer by layer to form the foundation of Pueblo Bonito's masonry. Their consistent size, many measuring almost identically, suggests careful design. The canyon itself provided this raw material, with its cliffs offering stone just steps from the construction site.

Timber Was Hauled Over 70 Miles To Reach The Canyon

Tree-ring dating reveals that the beams originated from distant mountain ranges, including the Chuska and San Mateo Mountains. As a result, massive logs, some exceeding 15 feet in length, were transported across desert terrain without the use of wagons or pack animals. This underscores an intentional and organized effort.

They Employed A Repeating Masonry Pattern Still Visible Today

Rows of thin sandstone slabs alternate with wider core sections to form a distinctive masonry style now known as the "Bonito-style". Builders applied mud mortar and inserted chinking stones to stabilize the walls. The result is a durable, rhythmic pattern still visible in surviving structures today.

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Multiple Construction Phases Spanned Over 300 Years

Construction at Pueblo Bonito didn't happen all at once. Early phases, beginning around 850 CE, featured ground-level room blocks. Over time, walls and kivas were added. Tree-ring dating reveals that the complex evolved in at least four major phases over a period of three centuries.

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Terraced Levels Prevented Structural Collapse On Slopes

The terrain of Chaco Canyon wasn't flat, but Pueblo Bonito adapted. Builders created terraced back walls that followed the canyon's natural incline. These tiered levels helped redistribute weight and ensure that stacked rooms didn't collapse under their mass.

Laurie McDonald, Wikimedia Commons

Laurie McDonald, Wikimedia Commons

Construction Followed Solar And Lunar Cycles

Several key walls and windows align with celestial events. The southeast wall marks sunrise on the winter solstice, while interior sightlines frame lunar standstill points—an 18.6-year cycle. These precise alignments suggest that builders timed phases of construction with astronomical significance in mind.

Drainage And Water Collection Systems Were Integrated Early On

Despite its arid setting, Pueblo Bonito included channels and diversion basins to manage rainwater. These features reduced erosion near foundations and may have supported short-term water storage. Their placement indicates that water management was an integral part of the original architectural plan, not an afterthought.

Most Rooms Lack Firepits Or Living Evidence

Though vast in number, the majority of Pueblo Bonito's rooms show no signs of daily domestic use. Less than 10% contain hearths or habitation layers. This absence suggests these spaces served other purposes—possibly administrative or ceremonial rather than residential.

Steven C. Price, Wikimedia Commons

Steven C. Price, Wikimedia Commons

Evidence Suggests Many Rooms Were For Storage

Sealed doorways and residue from stored goods point to long-term storage use. Excavations uncovered remnants of corn and grinding tools inside enclosed chambers. These rooms were likely secured to protect communal food stores and were not inhabited by families.

Dean Cleverdon, Wikimedia Commons

Dean Cleverdon, Wikimedia Commons

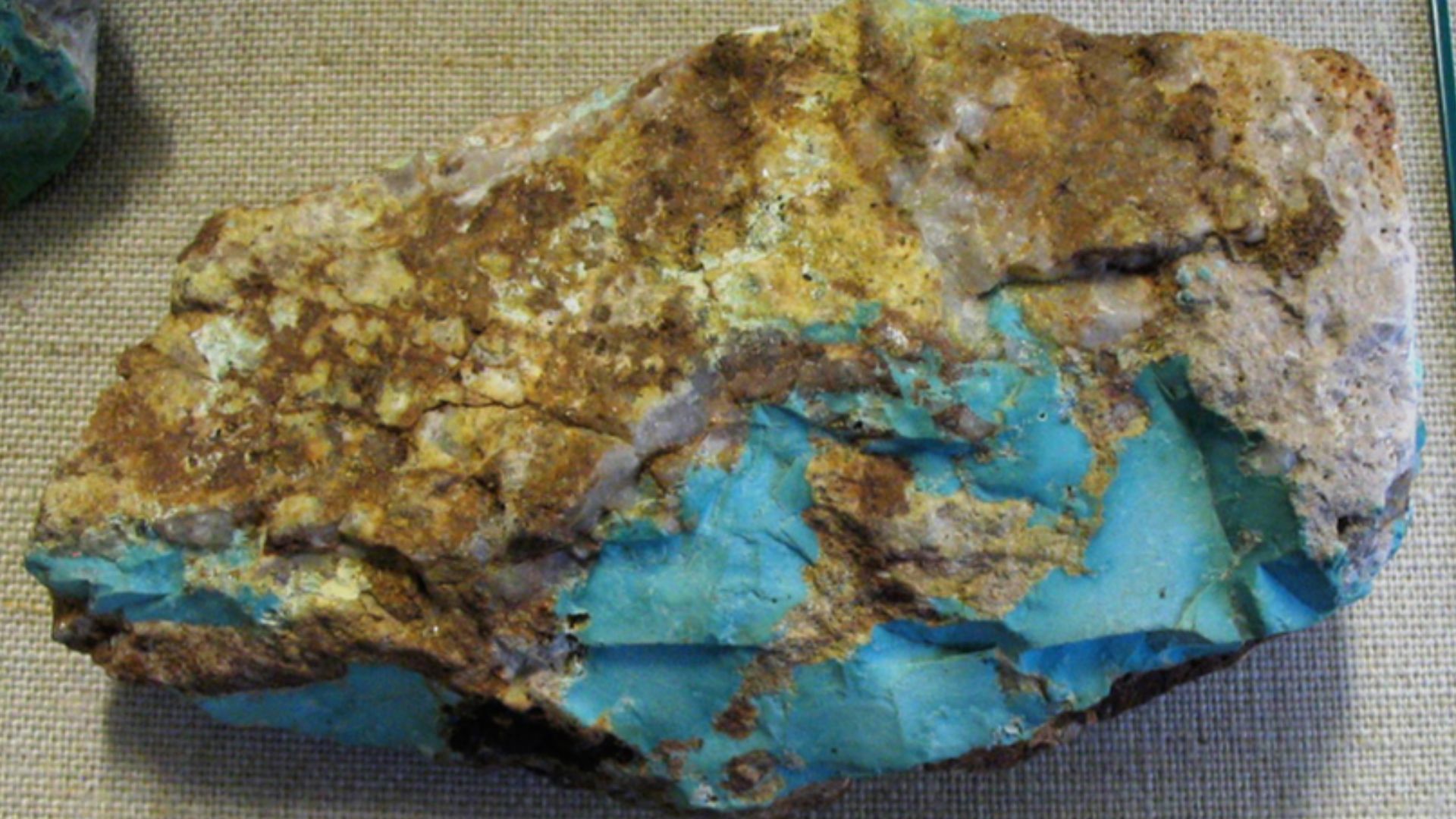

Room 33 Housed Elite Burials With Prestige Goods

In the northwest quadrant, Room 33 revealed two elite male burials interred beneath its floor. Surrounding them were over 11,000 turquoise pieces, copper bells, shell bracelets, and carved wooden flutes. Radiocarbon dating indicates that one burial occurred shortly after 800 CE, while the other occurred centuries later.

Room 33 Housed Elite Burials With Prestige Goods (Cont.)

DNA testing confirmed that both men shared a maternal lineage, suggesting that hereditary elite status was passed through the female line. The longevity of burial use in the same room implies its sacred role in ancestral memory. Additional interments, although less richly adorned, demonstrate that Room 33 continued to be a revered mortuary space for generations.

JacobCarr06, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

JacobCarr06, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Painted Murals And Plaster Indicate Ritual Interior Use

Traces of red and black pigments remain on interior plaster walls. These suggest murals once depicted symbolic imagery tied to ritual or belief. Some rooms feature layered plaster coats, which means they were maintained over generations and possibly reused for repeated ceremonial functions.

Artifacts Include Mesoamerican Macaws And Cacao Residue

Tropical feathers and residues reveal an ancient trade link. At least 17 scarlet macaws were buried at Chaco sites, some in Pueblo Bonito. Vessels also tested positive for cacao, native to Central America, which highlights ties to distant trade networks and perhaps elite or ritual consumption.

Miroyedov Kirill, Wikimedia Commons

Miroyedov Kirill, Wikimedia Commons

Rooms May Have Been Aligned With Ceremonial Pathways

Doorways and interior corridors appear to follow directional logic. Some sequences link plazas to kivas in symmetrical patterns to imply ritual procession routes. The spatial flow between chambers appears too consistent to be random, instead suggesting ceremonial choreography within the site's design.

Specific Room Blocks Reveal Use As Astronomical Trackers

Researchers found narrow wall openings and windows framing solar or lunar points. During winter solstice or lunar standstills, light passes through these features in alignment with cosmological events. This kind of precision suggests that the builders intentionally incorporated celestial observations into their architectural planning.

DNA Traces Show Power Passed Matrilineally

Burials beneath Room 33 offer rare genetic insight. Nine individuals interred over centuries shared a maternal lineage, as determined by mitochondrial DNA. This pattern suggests leadership or elite status was inherited through maternal lines, consistent with practices observed among modern Puebloan descendant communities today.

Status Was Linked To Exclusive Access To Ceremonial Spaces

Not all spaces at Pueblo Bonito were equally accessible. Some rooms were elevated or built with restricted entryways. Archaeological patterns suggest that these rooms were reserved for select individuals, reinforcing a system in which ceremonial access reflected a person's social or religious rank.

Few Cooking Areas Suggest Centralized Food Control

Excavations reveal that there are very few hearths or grinding bins across the vast site. This scarcity implies that food preparation may have occurred in designated zones or was managed communally. Centralized control over meals could reflect shared feasting practices or administrative regulation of resources.

Material Distribution Shows Inequity In Wealth And Access

Prestige items were not scattered evenly. High concentrations of turquoise and imported shells are primarily found in elite burials or restricted rooms. The absence of such artifacts in most residential areas signals clear social stratification and unequal access to luxury materials.

Aramgutang~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Aramgutang~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Ceremonial Events Likely Defined The Social Calendar

Chaco's public spaces—particularly kivas and plazas—were not decorative. Their structure and orientation suggest they hosted recurring events tied to solstices or harvests. These rituals likely helped organize time and maintain cohesion within the regional population.

National Park Service (United States), Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service (United States), Wikimedia Commons

Leadership May Have Been Tied To Cosmic Knowledge

Those who understood sky cycles may have wielded real authority. Alignments built into Pueblo Bonito required astronomical precision, and leaders who could predict solstices or lunar standstills may have gained spiritual legitimacy, thereby blending cosmology with governance in the Chacoan world.

Steve Jurvetson, Wikimedia Commons

Steve Jurvetson, Wikimedia Commons

Over 400 Miles Of Engineered Roads Radiate From Chaco

Straight-line roads carved through mesas and deserts connect Chaco Canyon to distant sites. Some measure over 30 feet wide and stretch across miles without deviation. These engineered paths reflect planning, likely supporting trade and ceremonial journeys across the region.

AlisonRuthHughes, Wikimedia Commons

AlisonRuthHughes, Wikimedia Commons

Over 400 Miles Of Engineered Roads Radiate From Chaco (Continued)

Some segments feature curbs and staircases carved into cliff faces, showcasing advanced construction techniques. The roads often ignore topography by running over ridges instead of around them. Their scale and orientation suggest symbolic importance and a connection to linked sacred territory, as well as settlements or economic centers.

Sites Like Chetro Ketl And Kin Kletso Mirror Bonito's Design

Just west of Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl and Kin Kletso rise with striking similarity. Each features core-and-veneer masonry and kivas positioned by astronomical principles. These parallels show how architectural norms and sacred design elements were replicated across major Chacoan sites.

Chaco Was Central To A Regional Network Of Great Houses

Over 150 known "great houses" spread across the Four Corners area tie back to Chaco. From Salmon Ruins to Aztec Ruins, these satellite communities exhibit Chacoan planning influences. This regional web suggests Chaco functioned not just as a center but as a unifying influence.

Nancymaness, Wikimedia Commons

Nancymaness, Wikimedia Commons

Trade Linked Chaco To Distant Mesoamerican Cultures

Artifacts excavated from Pueblo Bonito include cacao residue and the remains of macaw skeletons. These tropical goods are traced back to Mesoamerica. Long-distance exchange networks brought rare items into the canyon to reinforce Chaco's role as a trade hub that reached far beyond the Southwest.

AlejandroLinaresGarcia, Wikimedia Commons

AlejandroLinaresGarcia, Wikimedia Commons

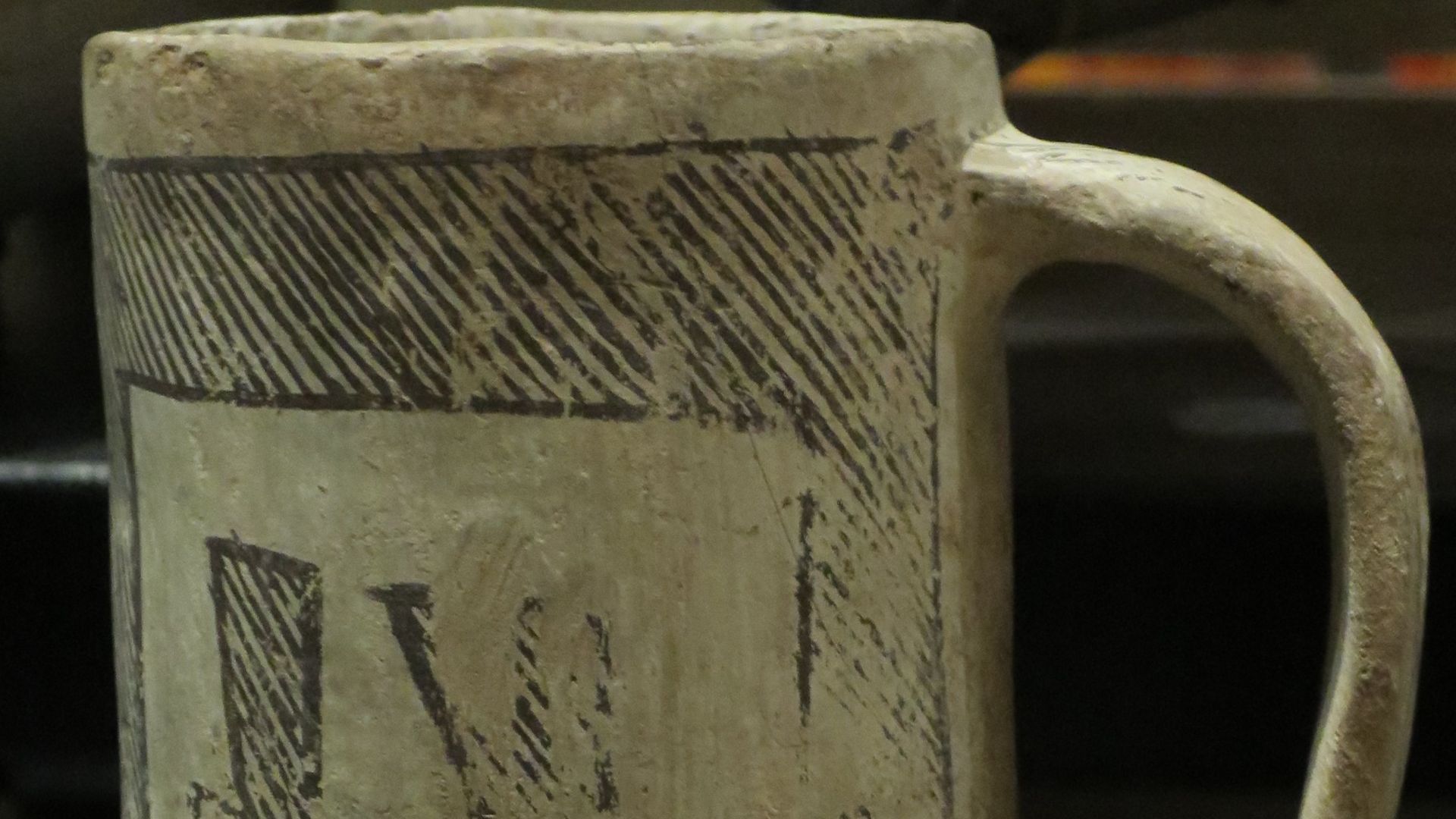

Ceramic Styles Were Standardized Across The Network

"Chaco Black-on-White" pottery appears not just in the canyon but at sites hundreds of miles away. Its spread suggests centralized production or shared cultural practices. Uniform styles and motifs helped visually link outlier communities to Chaco's social and ceremonial identity.

Signal Towers And Shrines Supported Inter-Site Communication

Stone cairns and elevated platforms may have functioned as signaling points using fire or reflective materials. Their placement near road intersections implies real-time coordination between distant Chaco-linked settlements. Archaeologists identified these features on ridgelines and canyon rims by highlighting their strategic visibility across the geography.

Pilgrimage May Have Driven Regional Movement

Not all travel was practical. Some roads lead to unoccupied or symbolic destinations. These paths, paired with monumental entry points, suggest ritual pilgrimage. Seasonal or ceremonial journeys helped reaffirm spiritual and political bonds across the far-flung Chacoan world.

AlisonRuthHughes, Wikimedia Commons

AlisonRuthHughes, Wikimedia Commons

Rediscovery Led To Early Archaeological Mishandling

By the late 1800s, treasure hunters and amateur archaeologists had begun to excavate Pueblo Bonito. These early efforts often lacked proper documentation or preservation. Artifacts were removed in bulk, and detailed site records were rarely kept, which compromised valuable archaeological context.

Pueblo Bonito Became A Protected Site In 1907

President Theodore Roosevelt declared Chaco Canyon a national monument in 1907 under the Antiquities Act. This act marked the beginning of a new era in scientific preservation. Controlled excavations and detailed documentation began replacing destructive extraction methods that had dominated archaeological work in the previous decades.