The Weight Of Wonder

In the ancient world, nobody had cranes or engines, but somehow, these civilizations raised stones the size of buses and built megastructures. They relied on brains, teamwork, tricks, and construction methods that still puzzle engineers today.

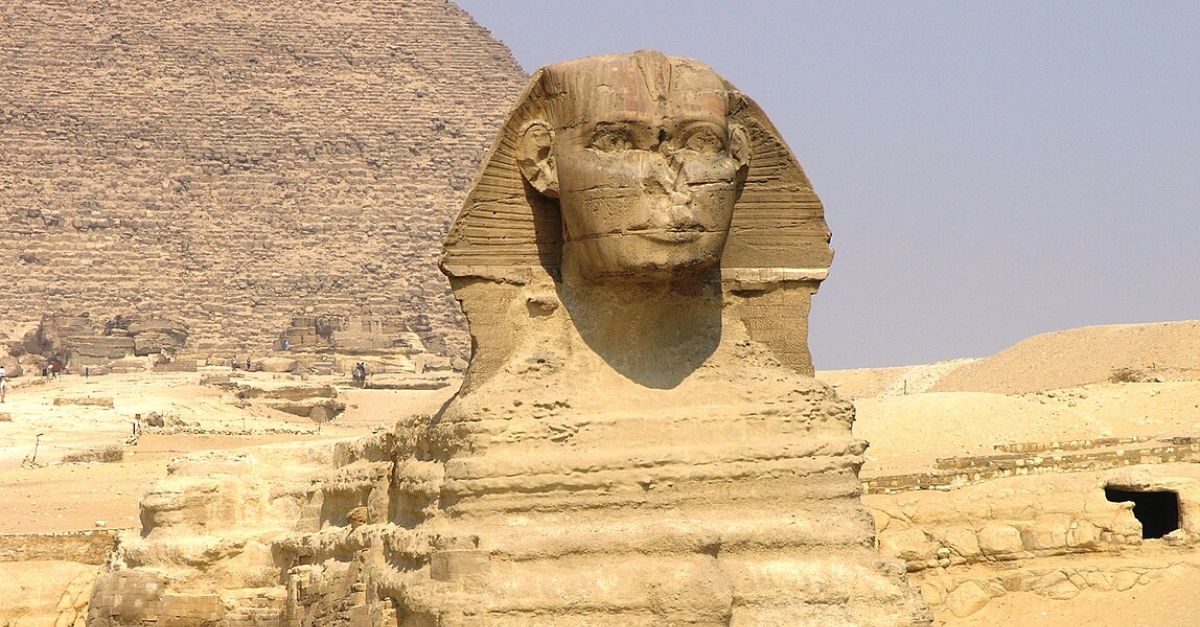

The Egyptian Pyramids, Giza

Thousands of years before cranes, Egyptian workers mastered balance and friction. They dragged limestone blocks on wooden sledges coated with water, which cut the drag in half. Tomb reliefs even show this clever trick, proving pyramid construction was rooted in physics and planning, not mystical power.

The Moai Of Easter Island

Giant stone heads didn’t just stand—they walked. Using ropes and rhythm, islanders “rocked” Moai statues upright along dirt paths. Each controlled tilt brought the figure forward like a slow dance. Archaeologists replicated the process to demonstrate teamwork and timing.

Horacio_Fernandez, Wikimedia Commons

Horacio_Fernandez, Wikimedia Commons

Stonehenge, England

Imagine hauling bluestones 150 miles without machines. Builders likely combined sledges, wooden rollers, and river rafts to cross the terrain. Tool marks near the site hint at coordinated labor crews working through seasons—engineering precision with ancient astronomy.

Mactographer, Wikimedia Commons

Mactographer, Wikimedia Commons

Sacsayhuaman Fortress, Peru

This Andean masterpiece fits together like a puzzle made for giants. Builders carved each block to match its neighbor perfectly—no mortar, just geometry. Using inclined planes and levers, workers locked the stones so tightly that earthquakes couldn’t shake them apart.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

The Temple Of Jupiter, Baalbek

Some stones at Baalbek weigh more than 800 tons. The builders likely used rollers and raised platforms to shift them into place, evenly distributing the pressure. Every block fits with mathematical precision. Roman engineers who expanded the site understood gravity as more than guesswork.

The Great Wall Of China

Stretching across mountains, the Great Wall demanded creative movement of stone and tamped earth. Workers used sledges, pulleys, and human chains to raise sections faster than beasts of burden could manage. The real marvel was the coordination across the terrain that few dared to cross.

Severin.stalder, Wikimedia Commons

Severin.stalder, Wikimedia Commons

Angkor Wat, Cambodia

Sandstone for Angkor’s temples was transported by raft along a network of canals. Each block was quarried miles away, carved with interlocking precision, then ferried downstream. The method saved time and reduced damage. Water, once again, became an ancient builder’s best transportation tool and quiet partner in design.

The Unfinished Obelisk Of Aswan

Still lying in its quarry, this half-carved monument exposes Egypt’s stoneworking secrets. Granite channels along its sides show where workers used dolerite balls to chip and separate it. When cracks appeared, they abandoned it—leaving behind the world’s most detailed record of ancient precision in progress.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

The Lion Gate Of Mycenae, Greece

A massive lintel stone crowns this Bronze Age gateway, lifted using earth ramps and timber scaffolds. Its twin lions symbolize power, but the gate’s endurance reveals skill. Builders balanced the load and weight so precisely that even after millennia, the structure stands perfectly aligned with its mountain view.

Joyofmuseums, Wikimedia Commons

Joyofmuseums, Wikimedia Commons

The Colossi Of Memnon, Egypt

Each colossal statue of Pharaoh Amenhotep III once stood guarding his mortuary temple. Carved from single blocks of quartzite hauled over 400 miles, they reached Thebes via sledges and river transport. Despite floods, quakes, and time, those seated giants still echo ancient engineering confidence.

MusikAnimal, Wikimedia Commons

MusikAnimal, Wikimedia Commons

Ollantaytambo Fortress, Peru

High in the Sacred Valley, workers transported enormous pink granite blocks from a quarry across the river. They built stone ramps and rolled each piece uphill on logs. The precision joints still visible today highlight how perfectly ancient masons combined brute strength with architectural foresight.

Puma Punku, Bolivia

Angular stones at Puma Punku fit together with machine-like precision. Carved andesite blocks, weighing tons, were shaped using copper chisels and sand abrasion. Transported from quarries miles away, these stones show an advanced grasp of geometry and weight balance long before modern tools existed.

Tiwanaku Temple, Bolivia

Near Lake Titicaca, Tiwanaku’s builders moved volcanic stones weighing hundreds of tons across high-altitude terrain. Ramps, ropes, and llama-driven sledges likely aided the process. Each stone’s alignment reflects careful astronomical planning, in which ancient Andean builders linked engineering and cosmology into one enduring monument.

Mhwater at Dutch Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Mhwater at Dutch Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Machu Picchu, Peru

On a ridge above the Urubamba River, workers shaped and positioned stones so precisely that no mortar was needed. They rolled or levered granite blocks into place along narrow terraces. Earthquakes have shaken the Andes for centuries, but Machu Picchu still clings flawlessly to its mountain spine.

RAF-YYC from Calgary, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

RAF-YYC from Calgary, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

The Temple Of Amun, Karnak

Rising obelisks once towered here, hauled upright using sand-filled pits and carefully removed ramps. Each piece of granite, carved in Aswan, journeyed north via canal. The site’s symmetry reflects a mathematical awareness, as ancient Egypt built for perfect balance.

Jorge Láscar from Melbourne, Australia, Wikimedia Commons

Jorge Láscar from Melbourne, Australia, Wikimedia Commons

Gobekli Tepe, Turkey

T-shaped limestone pillars, carved with animal reliefs, were moved by Neolithic hands long before the advent of metal. Stones that weighed several tons were dragged uphill using ropes and leverage. This construction’s circular arrangement hints at ritual precision and cooperation on a scale rare for early human settlements.

Klaus-Peter Simon, Wikimedia Commons

Klaus-Peter Simon, Wikimedia Commons

Hagar Qim, Malta

The workers here used rollers made from tree trunks to transport limestone slabs weighing over 20 tons. The temple’s doorway aligns with the solstice sun, revealing an advanced sense of design. Even after five millennia, its corbelled roof still shows how weight can be tamed by geometry.

Hamelin de Guettelet, Wikimedia Commons

Hamelin de Guettelet, Wikimedia Commons

Borobudur Temple, Indonesia

Over two million stone blocks form Borobudur’s massive structure. Each volcanic stone was quarried nearby, lifted by bamboo scaffolds, and stacked layer by layer. Drainage channels carved into the blocks kept rainwater from eroding them—a subtle yet brilliant feature that shows their architectural mastery.

Persepolis, Iran

The construction workers on this project carved terraces directly from bedrock, then hoisted massive stone columns using ramps and lifting devices. The precision of the joinery highlights experienced craftsmen coordinating large labor teams. Persepolis was a declaration that stone, properly managed, could command both strength and grace.

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Ramesseum Statues, Egypt

These monumental figures of Ramses II were carved from single granite pieces hauled across desert sands. Workers dragged them on wooden sledges greased with animal fat to reduce friction. Their sheer scale turned every movement into choreography.

Marc Ryckaert, Wikimedia Commons

Marc Ryckaert, Wikimedia Commons

Gobekli Tepe Pillar Construction, Turkey

The workers here used hammerstones and limestone chisels to shape the tall pillars, then dragged them across the hill using braided rope. Postholes were carefully positioned in circular patterns. The site’s organization was a complex planning in play, with pillars balancing for stability long before architectural blueprints existed.

Radosław Botev, Wikimedia Commons

Radosław Botev, Wikimedia Commons

Temple Of Jupiter Foundation Stones, Lebanon

The Trilithon blocks at Baalbek each weigh more than 1,000 tons. The workers likely used sledges on rollers with incremental lifting via levers and soil packing. Precision jointing kept the platform stable. The result was a profound grasp of load distribution that rivals modern civil engineering practices.

Lodo from Moscow, Russia, Wikimedia Commons

Lodo from Moscow, Russia, Wikimedia Commons

Tomb Of Khufu Boat Pits, Egypt

Besides the Great Pyramid, ancient workers buried full-sized cedar boats used to ferry massive stones along the Nile. Their preserved hulls show mortise-and-tenon joinery—no nails, just interlocking wood. These vessels represent an early example of logistical planning for the transport of monumental construction materials.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Trilithon Stones, Baalbek

Stacked at the Temple of Jupiter’s base, the Trilithon stones were positioned with minimal gaps. Engineers estimate hundreds of laborers used wooden rollers and counterweights for micro-adjustments. These blocks’s placement was done so well that they remain steady today.

Ralph Ellis, Wikimedia Commons

Ralph Ellis, Wikimedia Commons

Karnak Temple Obelisk Placement, Egypt

To stand obelisks upright, engineers filled sand pits beneath each shaft. Workers removed sand gradually, allowing gravity to lower the base into position safely. This controlled descent prevented fractures, making Karnak one of the best-preserved showcases of ancient mechanical thinking in temple design.