The High Desert

In the wide, wind-carved flatlands of Oregon, a volcanic ring rises like a question. Its walls hold no lava; its past no easy story. Fort Rock stands alone, and its silence tells more than most eruptions ever did.

A Volcano Without A Mountain Chain

Fort Rock rises alone in Oregon’s high desert, over 70 miles from the Cascades, within the Brothers Fault Zone, but not part of a volcanic chain. Unlike typical volcanoes shaped by tectonic forces, this crater formed in isolation and remains a geologically distinct location.

Rvannatta at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Rvannatta at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

The Day Steam Tore Through Earth

It started not with a flame but with a collision. As magma rose beneath the Ice Age water table, it struck cold groundwater by triggering instant superheating. Steam built rapidly and then burst through the surface in an explosive blast. Ash soared, and a wide tuff ring formed, but lava never emerged.

Loren Kerns from Tigard, Oregon, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Loren Kerns from Tigard, Oregon, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Fort Rock Formed Underwater—Inland Water

Long after the “eruption” ended, waves took over. Fort Rock sat surrounded by Lake Fort Rock, an Ice Age body stretching 900 square miles. Terraces on its walls show where water repeatedly lapped against the crater. This motion gradually sculpted volcanic ash into coastal ledges under a now-vanished lake.

Robert P. VanNatta, Wikimedia Commons

Robert P. VanNatta, Wikimedia Commons

This Crater Never Carried Lava

Fort Rock didn't ooze lava. It exploded upward from a single site when magma met groundwater underground. Ash and steam surged out violently to form a wide crater. Its rim hardened into tuff, a rock made of compacted ash. The eruption stopped as abruptly as it had started.

Fort Rock: A unique volcanic landmark, Oregon by Matt.Cook.Oregon

Fort Rock: A unique volcanic landmark, Oregon by Matt.Cook.Oregon

This Crater Never Carried Lava (Cont.)

Tuff, the dominant rock here, lacks the texture and composition of solidified lava. Unlike basalt flows found at nearby sites, Fort Rock's material is crumbly, porous, and light. Its classification as a maar volcano reflects this difference, as it is formed entirely by explosive steam, not molten rock movement.

Forest Service, Wikimedia Commons

Forest Service, Wikimedia Commons

Settlers Named It For What It Looked Like

Long before geologists arrived, settlers gave it a name. In the late 1800s, wagon travelers referred to it as "Fort Rock" because its high, ringed walls resembled a frontier outpost. The name held its own, even though no structure and no military history existed there at all.

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

The Eruption's Signature Still Lingers In The Ash

Ash leaves a longer trail than memory. In nearby fields, geologists have mapped tephra layers linked to Fort Rock's eruption. Distinct sequences of fine ash and coarser lapilli reveal that the explosion occurred in stages, each tied to separate bursts of pressurized underground steam.

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

The Eruption's Signature Still Lingers In The Ash (Cont.)

These tephra deposits are grain-sized, and their mineral content helps volcanologists reconstruct the intensity and frequency of eruptive phases. The ash layers near Fort Rock have been cross-referenced with those in other Basin and Range fields to gain a better understanding of regional volcanic timelines.

Loren Kerns from Tigard, Oregon, USA, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Loren Kerns from Tigard, Oregon, USA, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Oregon's Dry Heart Was Once A Waterbird Haven

Before the land dried out, birds thrived in this area. Fossilized bones and eggshells in nearby lakebeds confirm that grebes and ducks once filled the wetlands. Paleoecological surveys indicate that this region supported seasonal habitats that attracted large flocks of migratory waterbirds during the late Pleistocene.

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

The Hidden Volcanic Field Few Recognize

The Fort Rock–Christmas Lake Valley Volcanic Field includes over 40 eruption sites shaped by explosive steam-driven activity. Among these are maar craters and cinder cones. Though Fort Rock is the most visible, many visitors never realize it's only one part of a larger volcanic system.

John Atherton, Wikimedia Commons

John Atherton, Wikimedia Commons

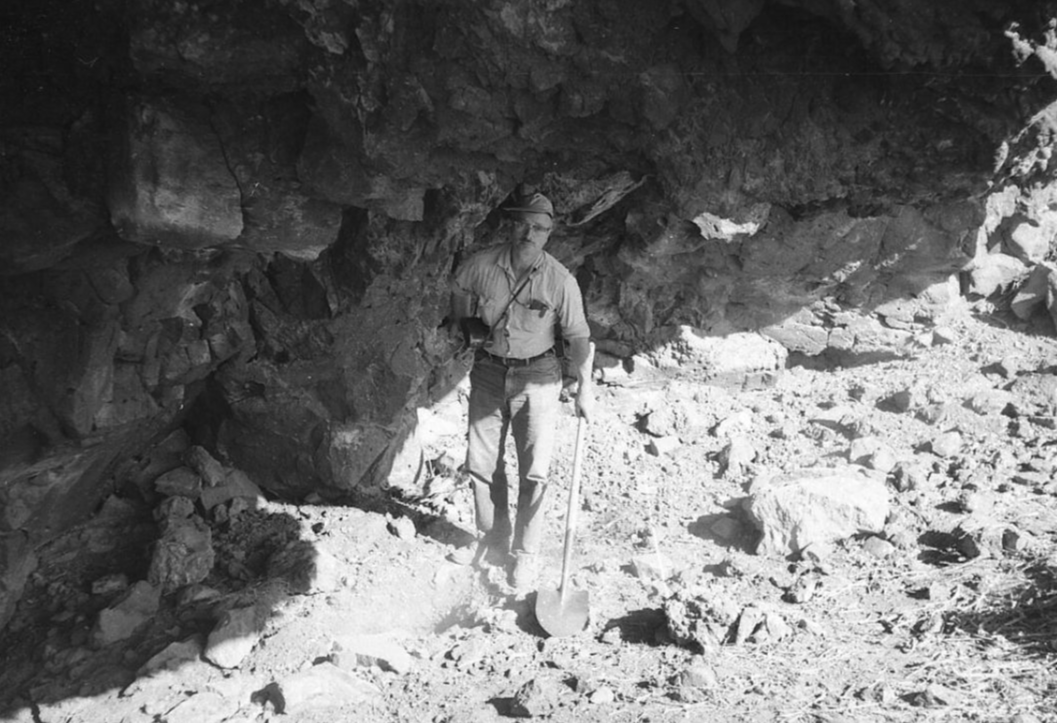

Sandals Over 9,000 Years Old Came From Its Cave

In 1938, archeologist Luther Cressman uncovered sagebrush bark sandals buried in volcanic ash near Fort Rock. Radiocarbon tests later dated them to between 9,350 and 10,500 years ago. The discovery came from Fort Rock Cave, just west of the crater, and revealed one of North America's oldest footwear finds.

John Atherton, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

John Atherton, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cressman's Discovery Rewrote American Prehistory

Many researchers doubted his findings. Cressman had claimed humans lived in Oregon over 9,000 years ago, a timeline few accepted at the time. Later advances in dating confirmed his results and helped reshape migration theories, which showed early people thrived far inland as the Ice Age waned.

Desert Winds Are Slowly Taking It Back

LiDAR scans now show that erosion is winning. Since Fort Rock's eruption, blasting desert winds have chipped at its tuff walls by carving pockets and hollows. The wind hasn't stopped, as its slow persistence, recorded across decades, is reshaping what the eruption left behind.

Desert Winds Are Slowly Taking It Back (Cont.)

Images from the 1940s compared to today reveal collapsing ledges and shrinking rims, most notably on the southern face. Fort Rock's tuff lacks the density of basalt, which makes it fragile. Without vegetation to stabilize the surface, erosion continues—a gradual collapse documented through surveys and historical photography.

John Atherton, Wikimedia Commons

John Atherton, Wikimedia Commons

Fossil Pollen Reveals A Greener Past

Pollen cores from near Fort Rock reveal a time when spruce and cattail once grew in abundance. This plant record points to cooler, wetter conditions. Long before sagebrush took hold, the region was defined by marshy ecosystems during the late stages of the Pleistocene.

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

Camels And Mammoths Likely Watched It Rise

Fossil discoveries in Lake County confirm that Columbian mammoths and dire wolves lived in the region. Radiocarbon evidence indicates their presence during the formation of Fort Rock. This volcano's debut likely occurred as the Ice Age began to loosen its grip on the American West.

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

How Lake Fort Rock Slowly Vanished

As the Pleistocene era came to a close, temperatures rose, and glacial runoff decreased. Evaporation soon outpaced inflow, gradually shrinking Lake Fort Rock, and what remained were salt flats and cracked playa. Its disappearance was a long withdrawal that erased hundreds of square miles from the ancient basin.

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

Indigenous Memory Preserves A Different Narrative

Northern Paiute oral traditions recount stories of water hills and receding lakes—imagery that resonates with the ancient setting of Fort Rock. Though the site itself goes unnamed, the narratives align with known climate shifts. While science defines the field by eruptions, Indigenous stories frame it through memory and change.

Materialscientist, Wikimedia Commons

Materialscientist, Wikimedia Commons

Its Crater Had No Sacred Use On Record

Unlike Crater Lake, which holds a sacred legacy for the Klamath people, Fort Rock does not. Archaeologists have found no ceremonial structures or petroglyphs inside its ring. So, if you go to visit, you’ll be met with an interior filled with dust and no signs of spiritual tradition.

Zainubrazvi, Wikimedia Commons

Zainubrazvi, Wikimedia Commons

Its Nearest Neighbor Blew Even Bigger

Just 25 miles away, another eruption left a deeper scar. Hole-in-the-Ground is a maar crater nearly one mile wide and over 500 feet deep. Though larger in scale, it lacks Fort Rock's iconic ring wall, which remains its most recognizable feature on the Oregon desert floor.

Loren Kerns from Tigard, Oregon, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Loren Kerns from Tigard, Oregon, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Early Route-Markers Used It As A Compass Point

Before signs and maps, settlers followed what they could see. Fort Rock's distinctive ring served as a landmark for travelers crossing the Oregon Outback. Journal entries from mail riders and wagon caravans in the 1880s describe it as a fixed point of orientation across the wide, empty terrain.

brx0 from Portland, USA, Wikimedia Commons

brx0 from Portland, USA, Wikimedia Commons

The Fort Rock Ghost Town Withered With The Water

In 1908, settlers arrived near Fort Rock, drawn by promises of irrigation. The soil was disappointed, and the water kept fading. By the 1920s, most homesteads were abandoned. The town's short life mirrored the land's drying cycle, and all that’s left is a museum along with scattered historical relics.

The Site Was Designated A Landmark But Rarely Seen

Despite its designation as a National Natural Landmark in 1976, Fort Rock receives little foot traffic. Fewer than 10,000 visitors arrive each year. Its isolation and minimal promotion in Oregon's tourism network leave this geological and historical site largely unappreciated.

Maps Misrepresented Its Form For Decades

On early 20th-century maps, Fort Rock appeared warped—often drawn as a crescent, not a ring. Geologists only recognized its true shape after aerial photos became common. Surveyors had missed the full outline, which delayed its correct classification as a maar formed by steam-driven eruption.

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Its Shape Still Casts A Perfect Shadow

When the sun dips low, Fort Rock draws a perfect ring across the desert floor. Drone photography and satellite imagery confirm its symmetry. Despite erosion, its outline remains crisp—an architectural circle cut not by humans but by fire and time.

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons

Kingofthedead, Wikimedia Commons