Who Came Before Us?

The past holds more than our own history. For hundreds of thousands of years, other humans walked the Earth while shaping tools and survival itself. Although rarely spoken about, their presence manifests clearly in fossils.

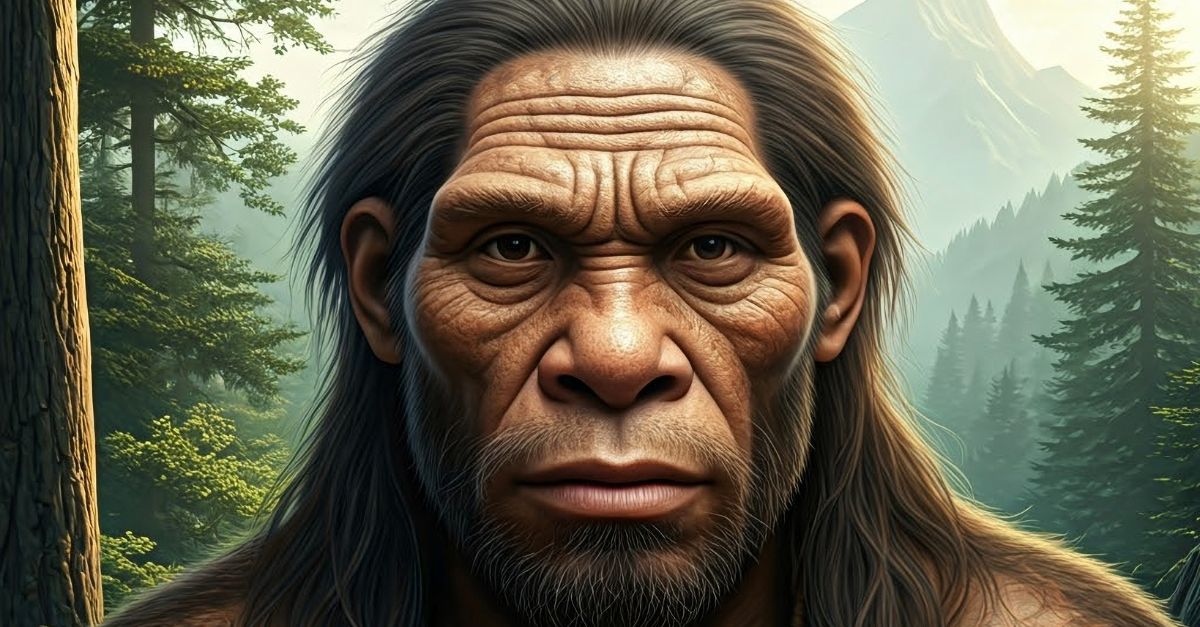

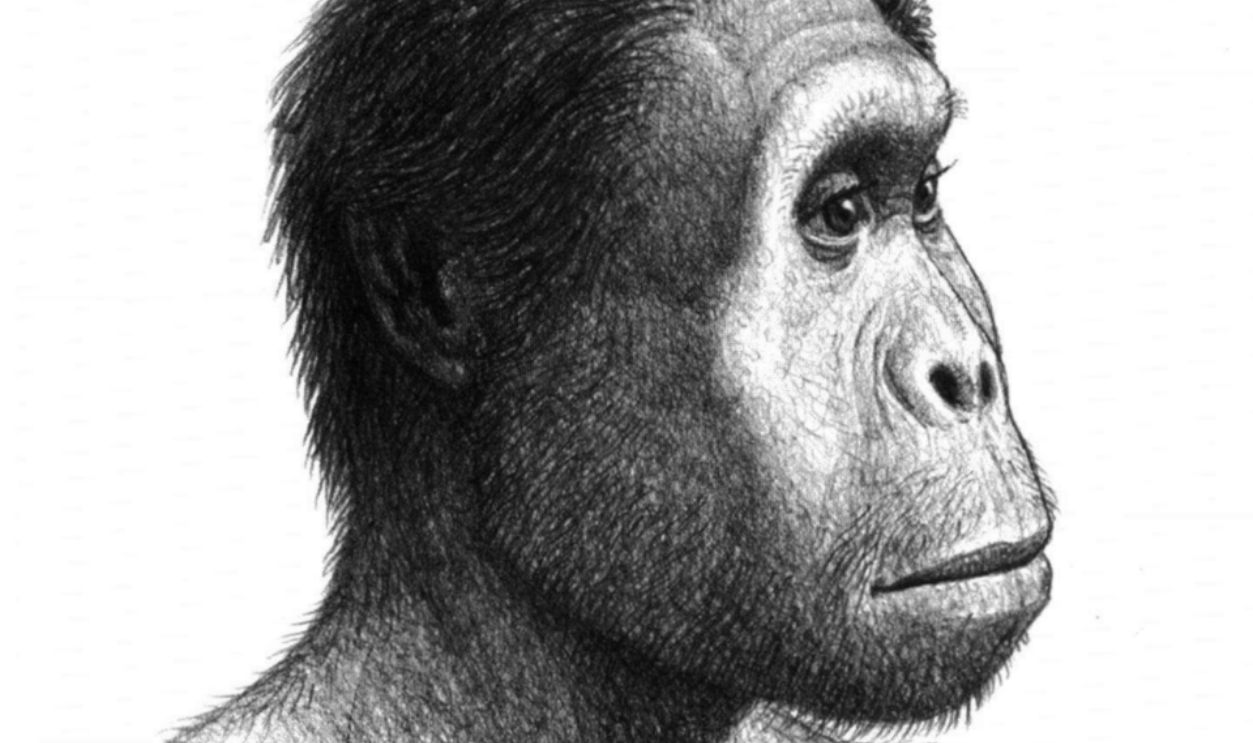

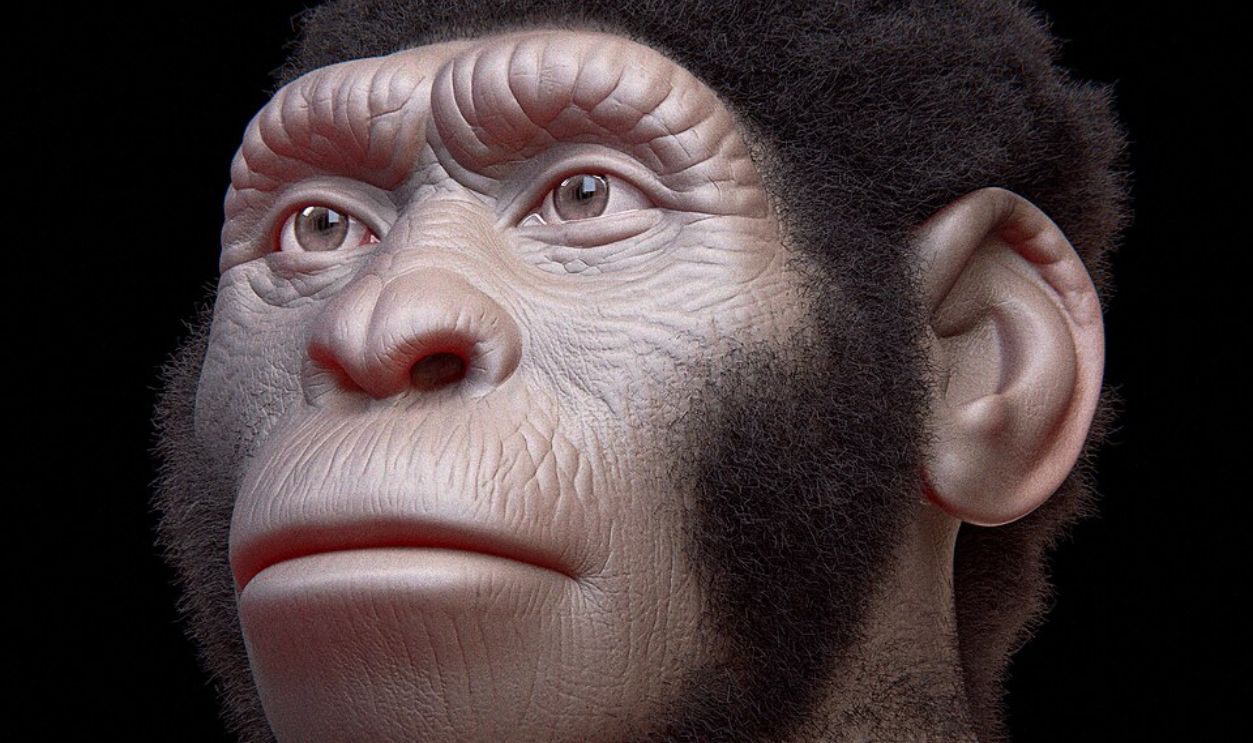

Homo Habilis

In East Africa between 2.4 and 1.4 million years ago, Homo habilis created early tools that left a mark. This innovation came to light at Olduvai Gorge, where Mary and Louis Leakey uncovered choppers and hammerstones used to butcher animals and process tough plants for food.

Homo Habilis (Cont.)

This species also showed brain growth, which ranged from 500 to 800 cubic centimeters. Even more telling, right-hand use appears in tool wear, and their hand bones reveal a precision grip. These signs together point to improving control and cleverness in how they shaped their world.

Cicero Moraes, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

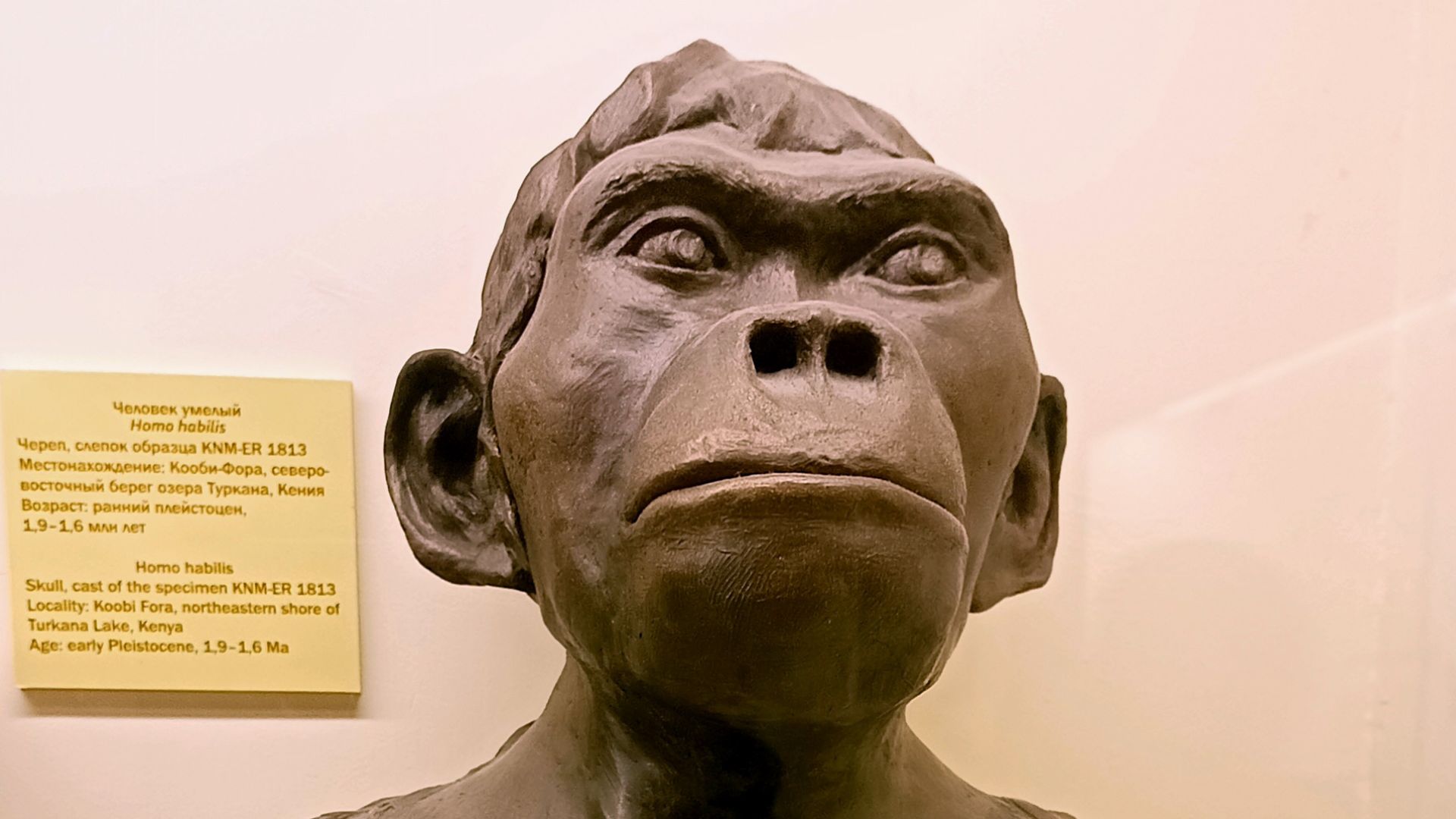

Homo Rudolfensis

Near Lake Turkana in Kenya, scientists uncovered the KNM-ER 1470 skull, dated to about 1.9 million years ago. With its flat face and a braincase around 775 cubic centimeters, the fossil points to a distinct human lineage shaped by unique dietary pressures.

Mauricio Antón, Wikimedia Commons

Mauricio Antón, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Rudolfensis (Cont.)

To support this idea, its broad premolars and thick enamel suggest a diet rich in hard or fibrous foods. Unlike Homo habilis, no stone tools were found nearby. So, scientists rely mainly on dental structure and wear to infer how it likely fed.

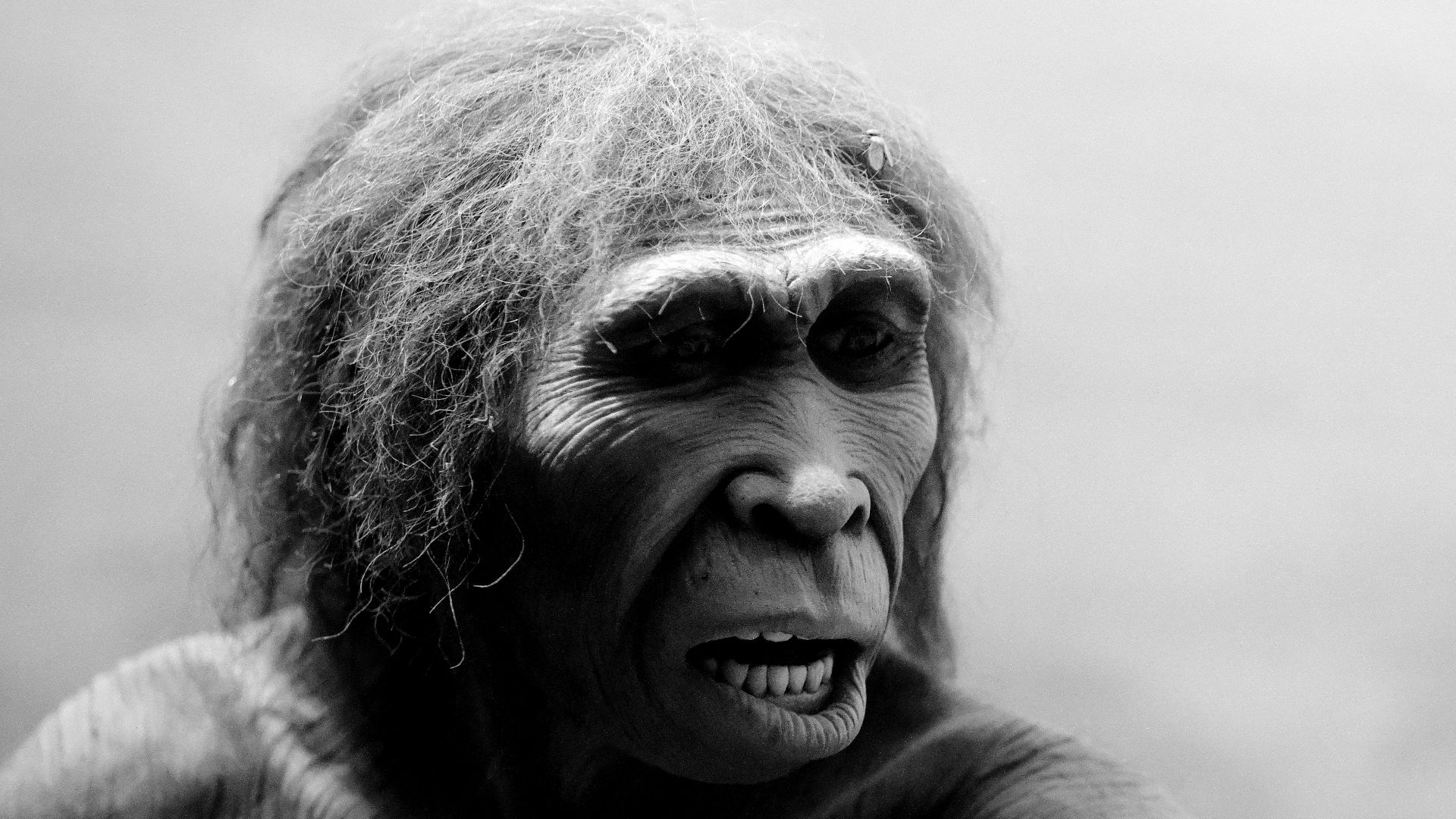

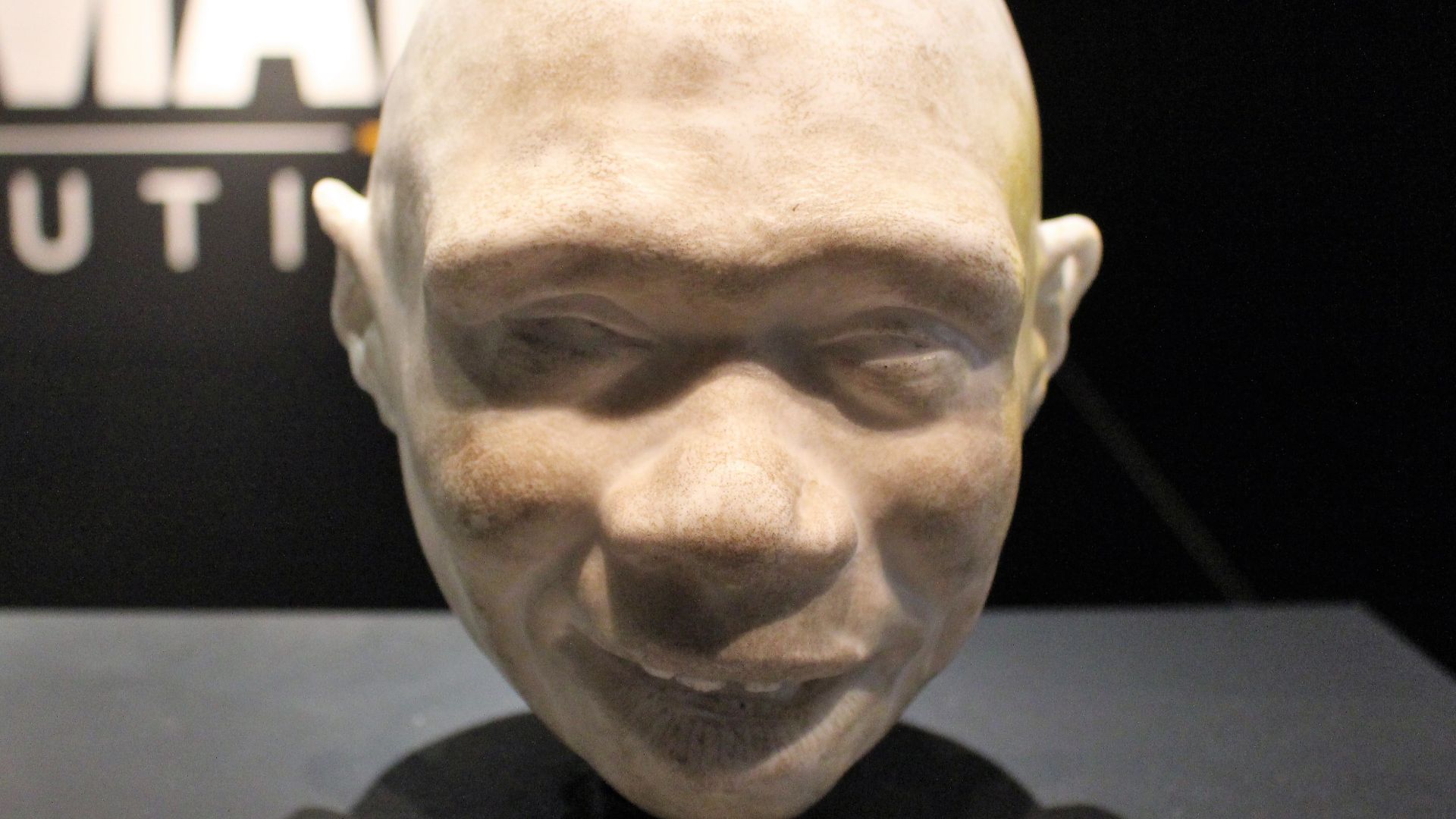

Homo Ergaster

The famous Turkana Boy skeleton, estimated to be from 1.5 or 1.6 million years ago, shows a body built for movement. Standing about 1.6 meters tall with longer limbs, he likely ran well. His brain size averaged 850–860 cubic centimeters, which suggests a growing mental ability in early Homo.

Neanderthal Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Ergaster (Cont.)

Tool use backs that up. Around 1.7 million years ago, they crafted handaxes and cleavers with care by using soft-hammer techniques. These Acheulean tools were a leap from earlier types and matched signs of large-animal butchery that pointed toward more skilled hunting strategies taking shape.

Werner Ustorf, Wikimedia Commons

Werner Ustorf, Wikimedia Commons

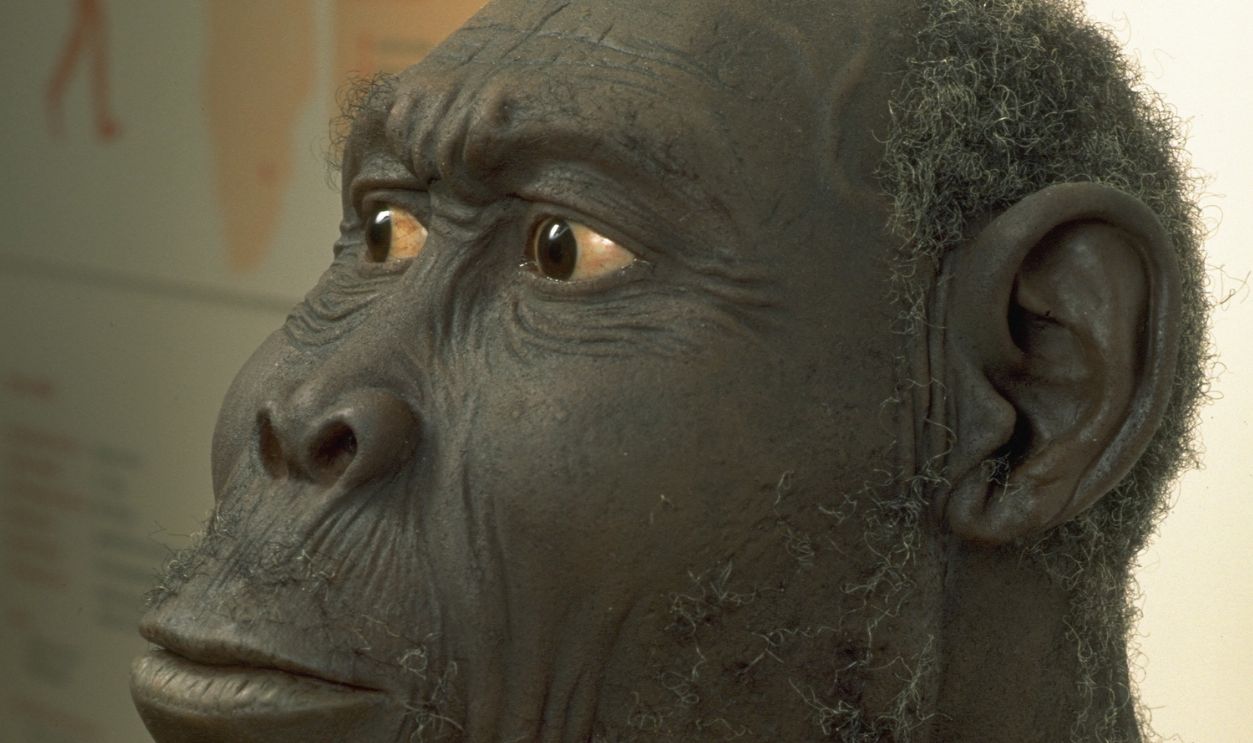

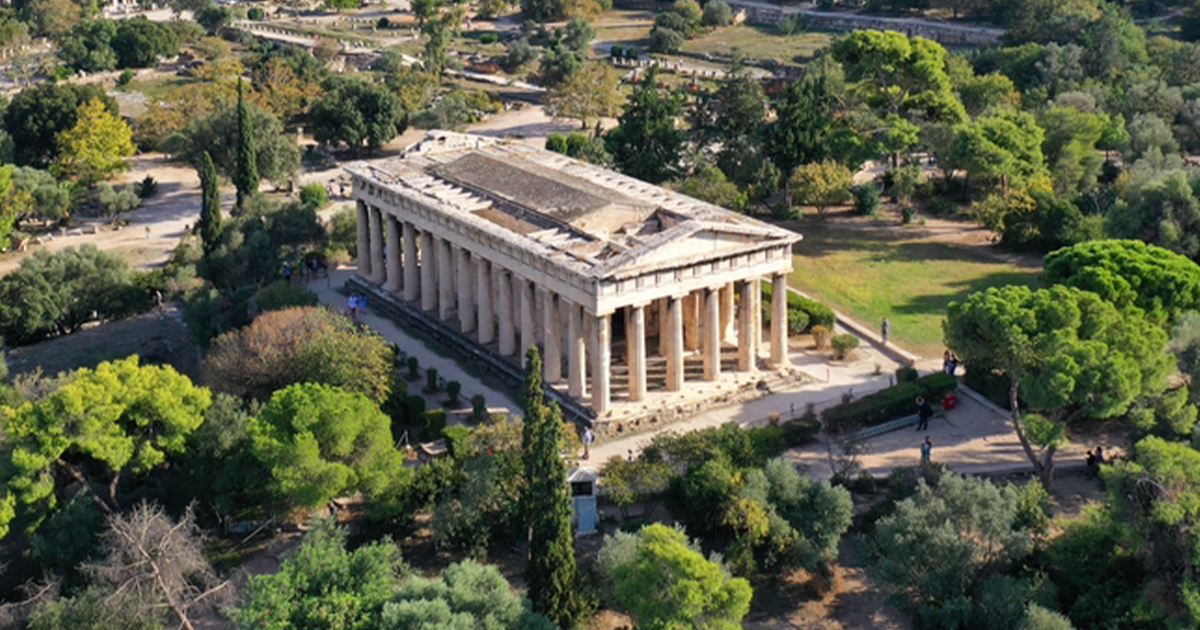

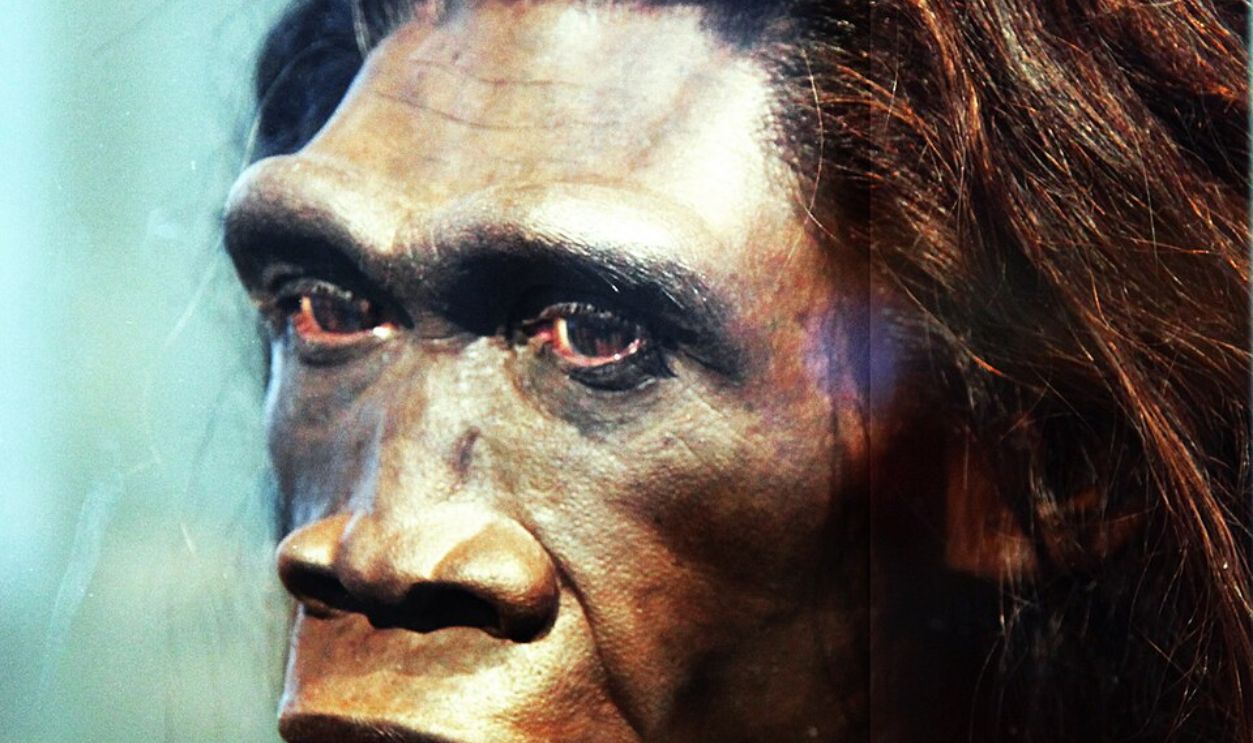

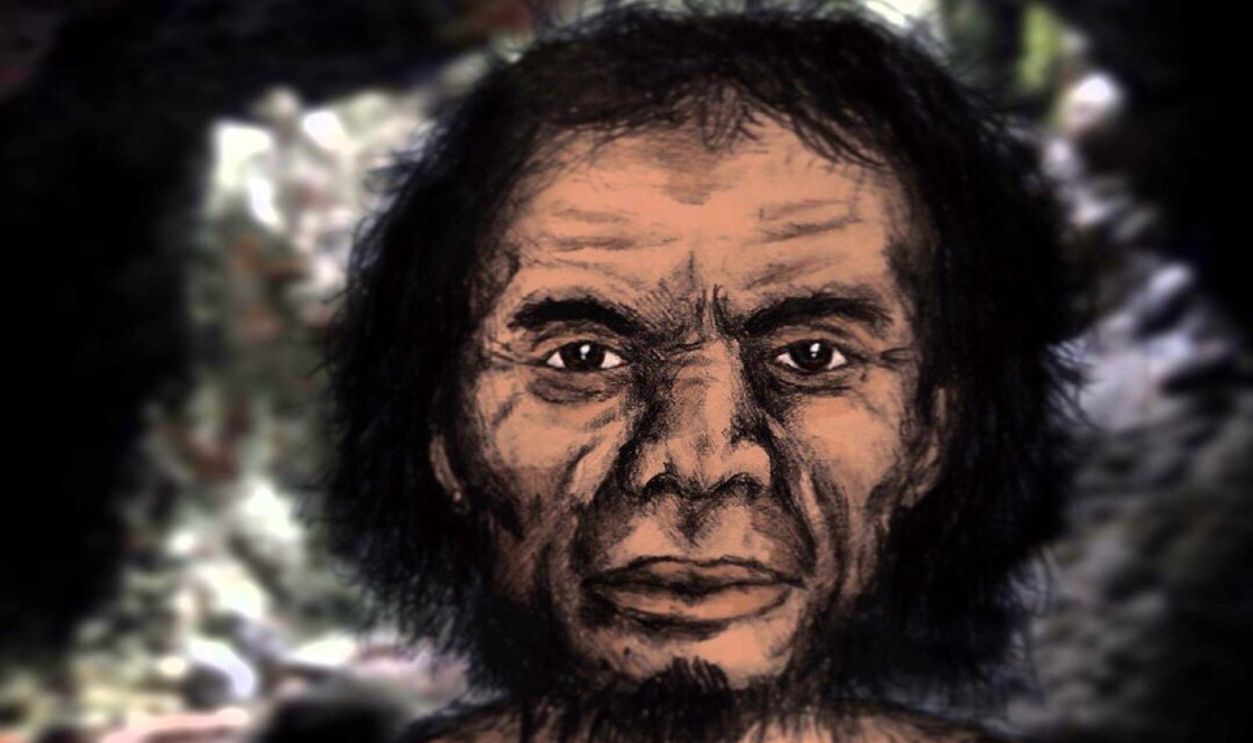

Homo Erectus

With long limbs built for endurance, Homo erectus was made to move. By 1.8 million years ago, they began spreading beyond Africa, reaching places as far as Georgia and Indonesia. Fossil evidence and their rugged skulls—paired with 900 cubic centimeter brains—show a species wired for survival and exploration.

Jakub Halun, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Jakub Halun, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Erectus (Cont.)

While traces of fire appear at Koobi Fora and Chesowanja around 1 million years ago, researchers debate whether it was controlled. Some evidence hints at fire use as early as 1.6 million years ago, but it becomes consistent only after 400,000 years, especially in hearth-rich sites like Israel.

Tim Evanson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Tim Evanson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

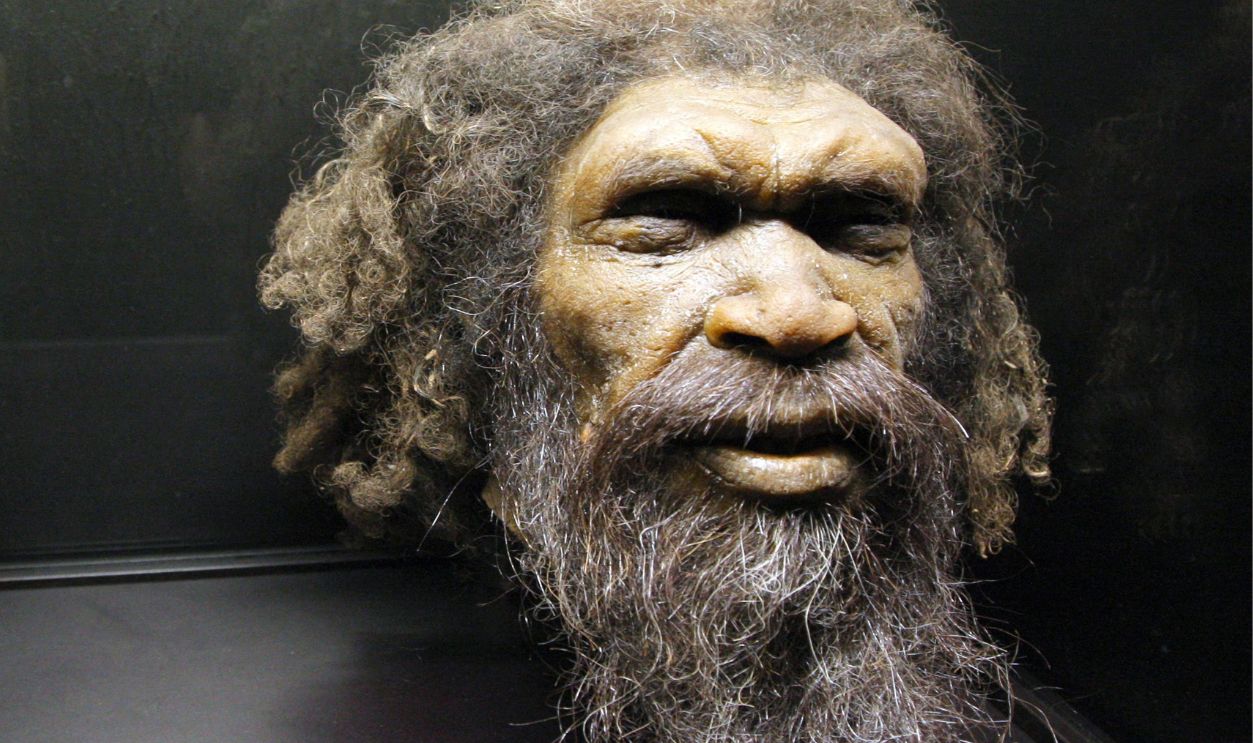

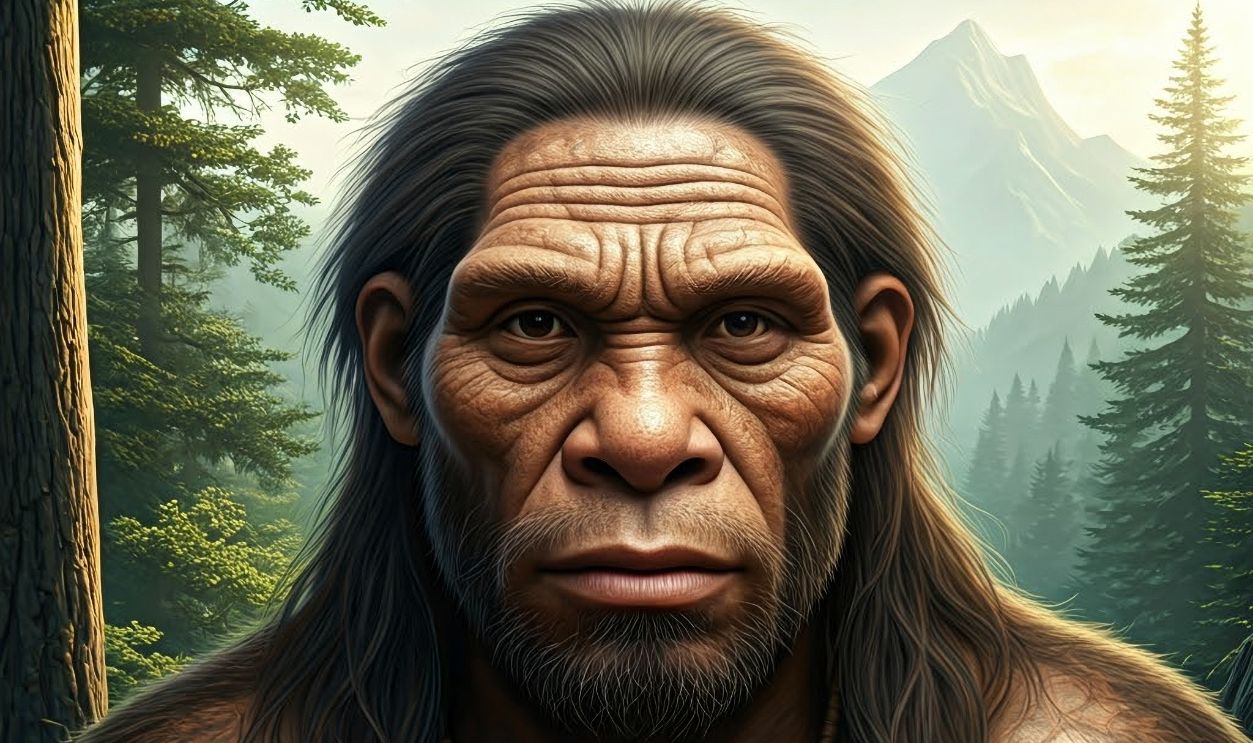

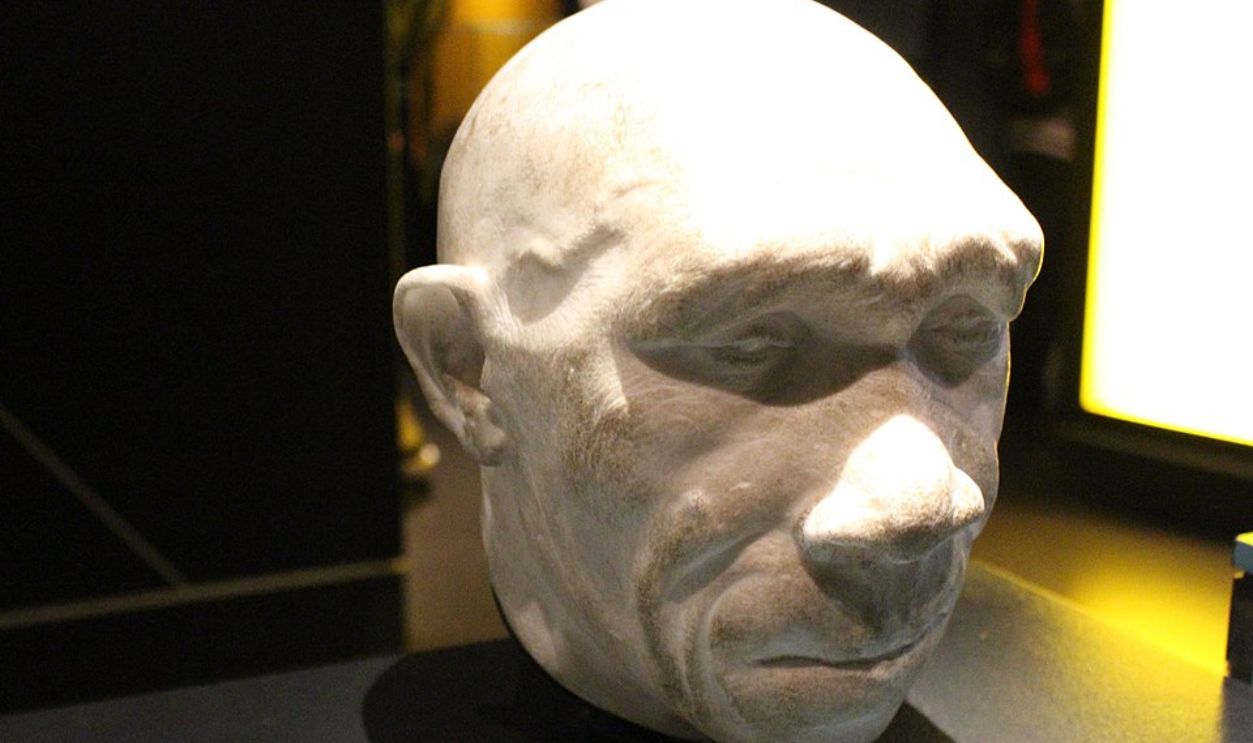

Homo Heidelbergensis

At Germany’s Schoningen site, researchers uncovered wooden spears used around 300,000 years ago to hunt large animals. Homo heidelbergensis was strong and smart, with a brain between 1,100 and 1,400 cubic centimeters. They spread across Europe and Africa between 700,000 and 200,000 years ago.

Emoke Denes, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Emoke Denes, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Heidelbergensis (Cont.)

Clues from France’s Terra Amata site add more detail to the picture. Hearths and possible shelters, estimated to be over 400,000 years old, suggest early domestic behavior. In the same layers, heated ochre and carved stones point to symbolic thinking beginning to take shape.

Cicero Moraes, Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Antecessor

Spain’s Gran Dolina cave revealed fossils of Homo antecessor dated between 850,000 and 780,000 years ago. Their brain reached about 1,000 cubic centimeters, and their face looked strikingly modern. As early Europeans, they seem to link older species with more recent human forms.

Emoke Denes, Wikimedia Commons

Emoke Denes, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Antecessor (Cont.)

Cut marks on bones at Gran Dolina point to nutritional cannibalism, a conclusion that has replaced older, now-disputed theories of ritual defleshing. While their growth patterns echo those of modern humans, researchers caution that symbolic behavior can’t be confirmed without stronger cultural evidence.

Raul Hernandez Gonzalez, Wikimedia Commons

Raul Hernandez Gonzalez, Wikimedia Commons

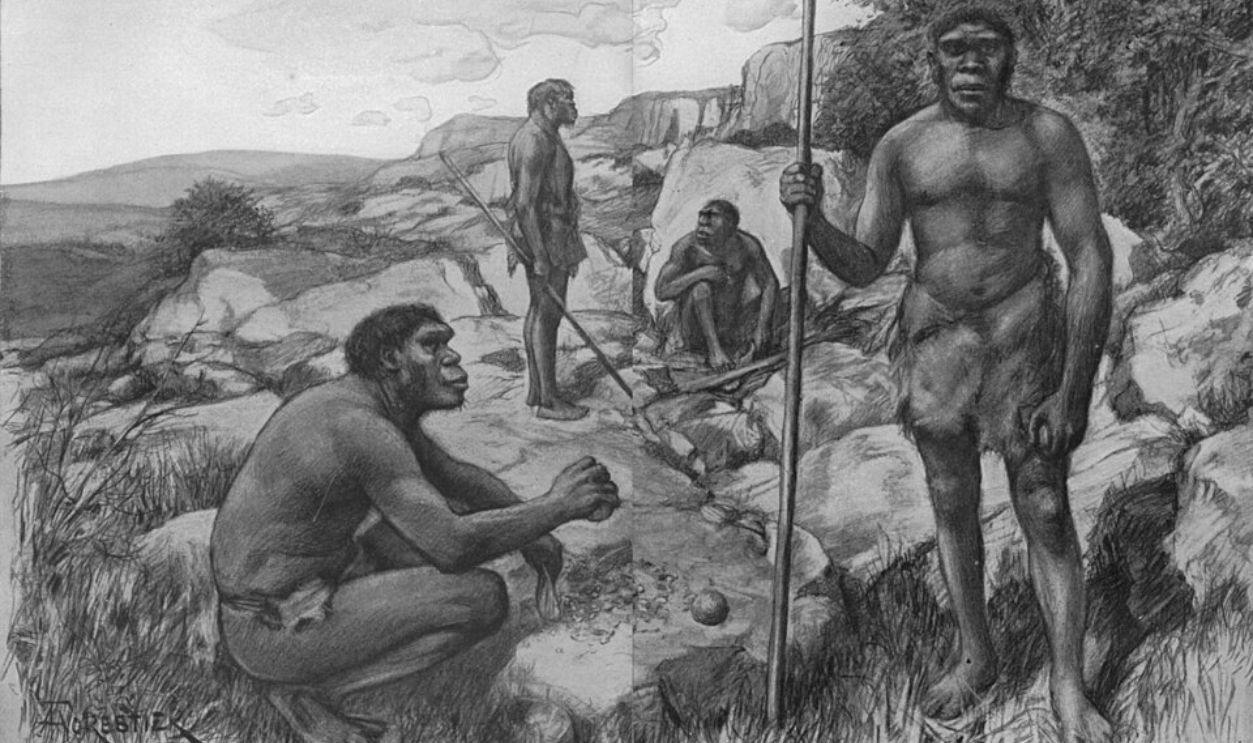

Homo Rhodesiensis

The Kabwe 1 skull, uncovered in Zambia and dated between 324,000 and 274,000 years ago, shows a broad, flat face with a heavy browridge. With a brain volume of about 1,230 cubic centimeters, many researchers consider this hominin a regional form of Homo heidelbergensis.

Amedee Forestier (1845 – 1930), Wikimedia Commons

Amedee Forestier (1845 – 1930), Wikimedia Commons

Homo Rhodesiensis (Cont.)

Supporting this view, the Bodo cranium from Ethiopia—Carbon-dated to roughly 600,000 years ago—shows cut marks linked to prehistoric defleshing. While once thought ritualistic, recent studies suggest symbolic intent remains uncertain, as the marks may reflect practical processing rather than any deliberate cultural behavior.

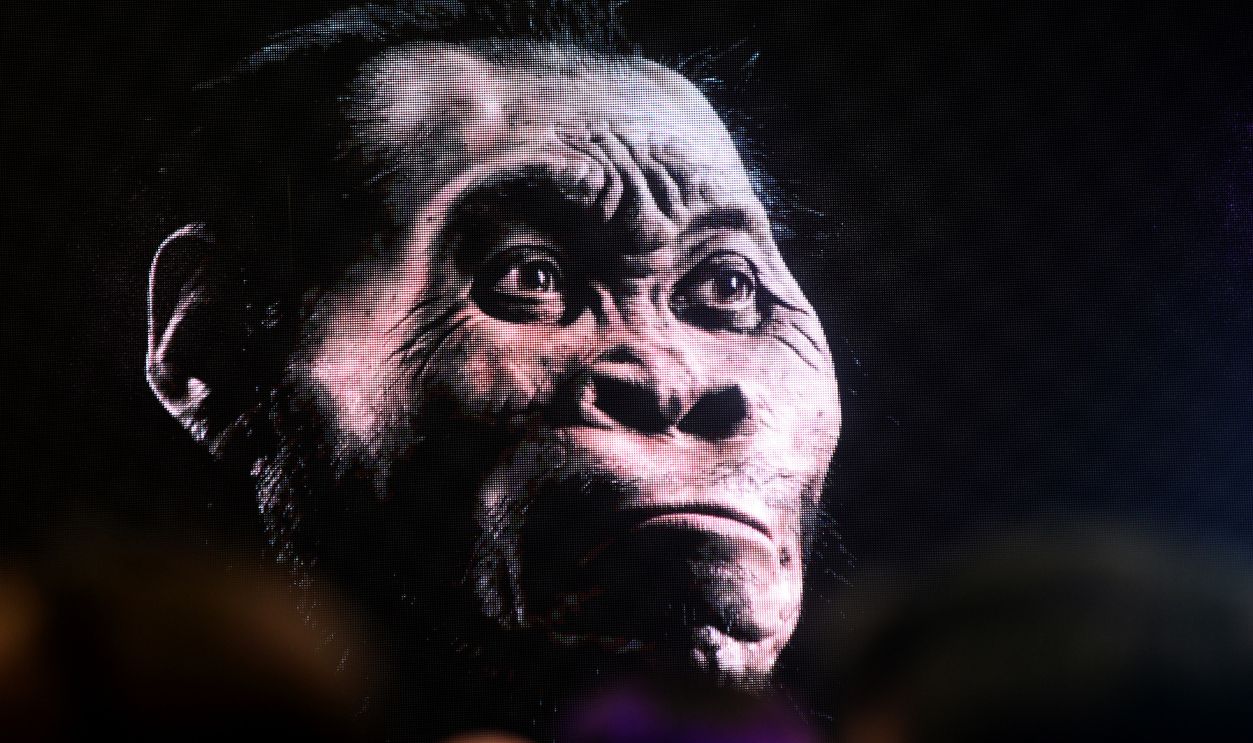

Homo Neanderthalensis

Well equipped for cold and rugged terrain, Neanderthals relied on Mousterian tools and the Levallois method to survive. Their strong builds and large brains, which reached up to 1,700 cubic centimeters, supported this lifestyle. They lived across Ice Age Europe and western Asia for thousands of years.

Homo Neanderthalensis (Cont.)

Inside Shanidar Cave, archaeologists uncovered Neanderthal graves dating back about 70,000 years. Although earlier claims of flower offerings based on pollen have been reinterpreted as likely natural in origin, signs of healed injuries and pigment use still suggest social care and hints of early symbolic thought.

Jakub Halun, Wikimedia Commons

Jakub Halun, Wikimedia Commons

Denisovans

From a Siberian cave, DNA found in a finger bone and teeth uncovered a distinct branch of the human family tree. Although the fossil record is limited, Denisovans lived from about 400,000 to 30,000 years ago, separate from both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens.

Denisovans (Cont.)

Denisovans left behind genetic traces that remain active today. The EPAS1 gene, which helps Tibetans handle low-oxygen environments, came from them. Their DNA also appears in Papuan genomes, and a jawbone on the Tibetan Plateau shows early adaptation to high altitudes.

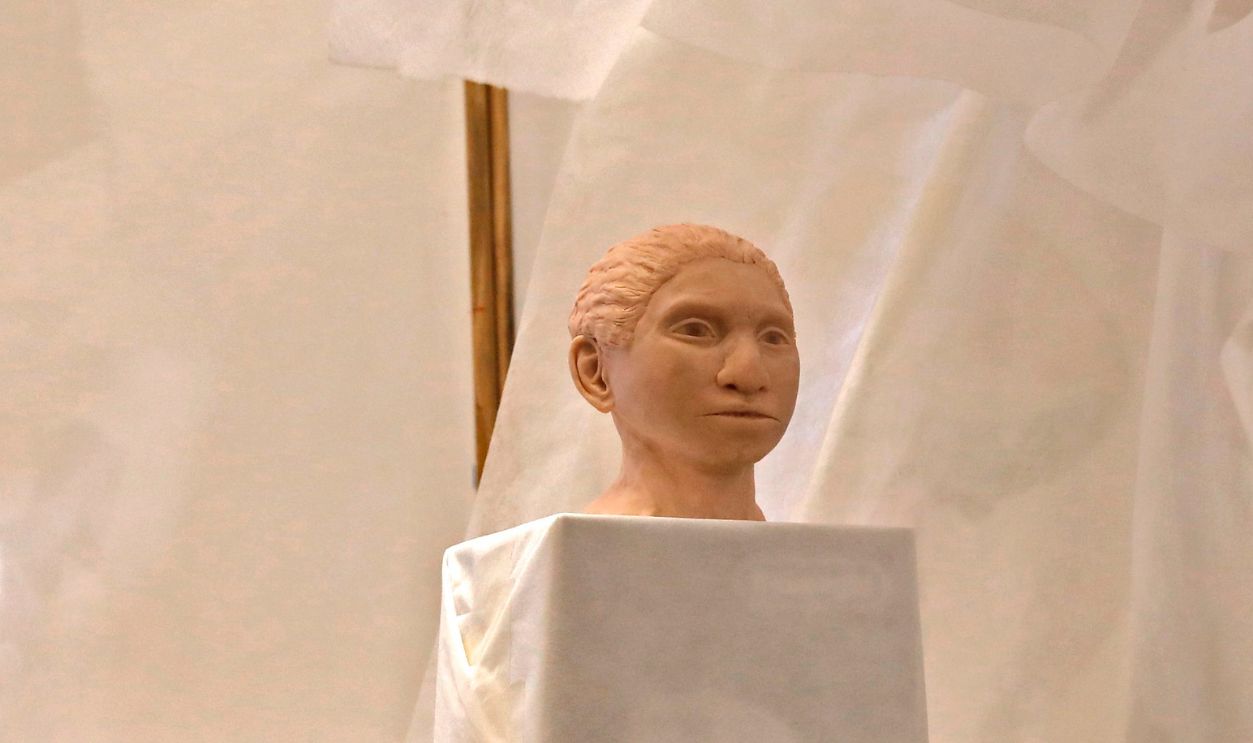

Homo Naledi

Homo naledi blended primitive traits with surprising modern ones, including wrist and foot bones that looked far more advanced than expected. Though their brains measured under 610 cubic centimeters and their shoulders curved like earlier species, their remains—found deep in South Africa’s Rising Star cave—tell a complex evolutionary story.

Cicero Moraes (Arc-Team) et alii, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes (Arc-Team) et alii, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Naledi (Cont.)

Far from the cave’s surface, at least 15 bodies were found in the Dinaledi and Lesedi chambers. Although some proposed intentional burial, a 2024 study in eLife found no sediment or tool evidence to support this, which rejects claims of symbolic behavior or purposeful body placement.

Homo Floresiensis

Just over a meter tall, Homo floresiensis lived on Flores Island between 100,000 and 60,000 years ago. They crafted simple Mode 1 tools and hunted dwarf elephants known as Stegodon. Their small stature and primitive traits suggest island dwarfism, likely evolving from earlier prehistoric human ancestors.

Cicero Moraes et alii, Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes et alii, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Floresiensis (Cont.)

Homo floresiensis hunted small animals and island megafauna using tools that changed very little over 700,000 years. This long stretch of stability likely came from an unchanging environment. With limited external pressures, isolation helped preserve both their physical traits and behaviors across many generations.

Cicero Moraes, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Luzonensis

Fossils found in the Philippines’s Callao Cave revealed a surprising mix of traits in Homo luzonensis. Traced to 134,000–50,000 years ago, these remains suggest that early humans entering Southeast Asia carried both Australopith-like and modern features, which hinted at more complex migration patterns than expected.

mkirader, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

mkirader, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Homo Luzonensis (Cont.)

Curved finger and toe bones suggest they were skilled climbers. And according to uranium-series dating, they may have lived in the cave as early as 134,000 years ago. Their existence supports repeated examples of isolated evolution in early Homo across Southeast Asian islands.

Luzonensis, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Luzonensis, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons