A Medieval Masterpiece With A Prehistoric Twist

In the mid-1400s, a French painter named Jean Fouquet created a remarkable work called the Melun Diptych. Today, it raises an unusual question: could an artist of his time have known about handaxes that were made thousands of years earlier?

The Life Of Jean Fouquet

Jean Fouquet, born around 1420 in Tours, served as court painter to Charles VII of France. He traveled to Italy, absorbed new Renaissance ideas, and introduced them back home. His style ended up combining French Gothic tradition with Italian perspective.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Art In 15th-Century France

During Fouquet’s time, French art was shifting. Gothic styles emphasizing ornament and devotion still dominated, but Renaissance influences from Italy were spreading. Artists began exploring naturalism and human-centered themes, while still working for powerful patrons who wanted art tied to religion and prestige.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Etienne Chevalier: The Patron

Etienne Chevalier was treasurer to King Charles VII, one of the most powerful officials in France. He commissioned the Diptych for his hometown of Melun. As a wealthy statesman, he sought to express both his deep Christian devotion and his social status through this work.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Overview Of The Melun Diptych

The Melun Diptych is a two-part painting, like a book with two facing pages. On one side stands Chevalier with St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr. On the other, the Virgin Mary sits with Christ, surrounded by angels. Together, they create an unforgettable mix of personal devotion and theological symbolism.

Daniel VILLAFRUELA., Wikimedia Commons

Daniel VILLAFRUELA., Wikimedia Commons

St. Stephen And His Patron

On the left panel, Etienne Chevalier kneels in prayer, his eyes turned upward. Beside him stands Saint Stephen. A stone rests on Stephen’s head, recalling the moment of his death—quietly tying Chevalier’s devotion to the story of sacrifice.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

The Symbolism Of Stoning In Christian Art

This detail was not accidental. Stoning often appeared in medieval art because it represented loyalty to faith even when facing death. Stephen’s story was the most famous example, and by placing him there, Fouquet made Chevalier’s devotion appear guarded by a saint who had endured ultimate suffering.

Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, Wikimedia Commons

Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, Wikimedia Commons

The Virgin And Child Enthroned

The right panel presents a striking contrast. Here, Mary sits high on a throne with the infant Christ on her lap. Her pale, marble-like face is calm but distant, as though she belongs to another world, which gives the scene an otherworldly and unsettling aura.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

The Celestial Court Of Angels

The background intensifies this feeling. Rows of angels dressed in blazing red and blue fill the space behind Mary. Their wings overlap in rhythmic patterns, almost overwhelming the eye. Instead of a soft vision of heaven, Fouquet offers a dazzling and unfamiliar spectacle.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Color And Mineral Resonance

The colors of the angels recall not just heaven but also the earthy intensity of minerals and stones. In a world where gems and rocks carried symbolic weight, these mineral-like colors may have heightened associations between his vision and stone objects.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Fouquet’s Stylistic Innovations

Seen together, the two panels reveal Fouquet’s daring approach. The left is grounded in lifelike realism, while the right is filled with dreamlike abstraction. This clash between the earthly and the heavenly created a painting unlike any other in France at the time.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

The Geometry Of The Composition

Fouquet built the Diptych with strong geometric balance. The sharp diagonals and pointed formations, especially in the angel wings, create a jagged, stone-like pattern. The structural geometry mirrors the chipped symmetry of a handaxe, where order emerges from fractured surfaces.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Flemish Painting Connections

Fouquet’s art shows clear links to Flemish masters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden. From them, he learned how to paint lifelike textures and capture light with precision. These techniques gave his portraits a realism rarely seen before in France.

Jan van Eyck, Wikimedia Commons

Jan van Eyck, Wikimedia Commons

How The Diptych Was First Received

When first displayed in Melun, the Diptych was admired as a masterpiece of devotion and innovation. Viewers saw Chevalier’s piety, Stephen’s martyrdom, and Mary’s majesty. It’s speculated that Mary’s appearance was modeled after Agnes Sorel, King Charles VII’s mistress.

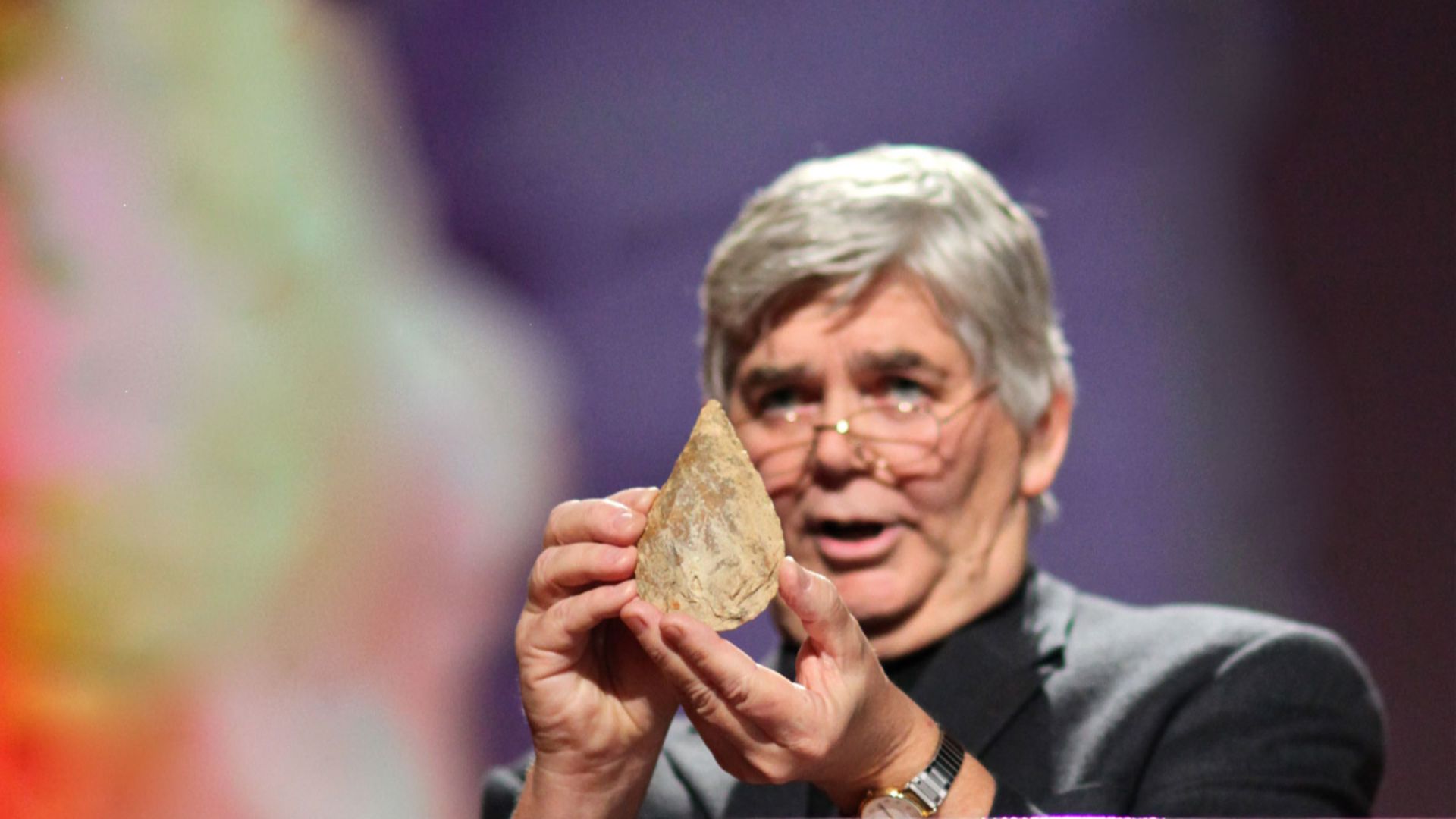

Who Made The Discovery

A study on it began with Steven Kangas, an art historian at Dartmouth, who thought the stone looked familiar. After attending a seminar and teaming up with anthropologist Jeremy DeSilva and Cambridge colleagues James Clark and Alastair Key, they launched scientific analysis.

Kenneth C. Zirkel, Wikimedia Commons

Kenneth C. Zirkel, Wikimedia Commons

Why The Question Was Raised

Kangas noticed that the painted stone beside Saint Stephen didn’t look like a random rock. Its chipped edges and symmetry resembled worked stone. This resemblance raised the question: Could Fouquet, centuries before archaeology, have depicted a genuine prehistoric tool?

Colchester Museums, Caroline McDonald, 2005-03-11 08:51:16, Wikimedia Commons

Colchester Museums, Caroline McDonald, 2005-03-11 08:51:16, Wikimedia Commons

Building The Case Step By Step

Before running formal tests, the team compared the Diptych’s stone with museum handaxes by eye. The visual similarities—shape and flake scars—were striking enough to justify scientific analysis. The similarities were too precise to ignore, pushing the team toward rigorous study.

Scientific Evidence Behind The Claim

Researchers compared the painted stone’s shape and flakes to actual Acheulean handaxes using Elliptical Fourier Analysis. They found a 95% match in shape, similar color variations, and matching flake-scar counts—strong evidence that Fouquet painted a real prehistoric tool.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme, Julian Watters, 2004-09-02 13:29:23, Wikimedia Commons

The Portable Antiquities Scheme, Julian Watters, 2004-09-02 13:29:23, Wikimedia Commons

The Importance Of The Discovery

This discovery pushes the timeline for handaxes’ cultural presence back centuries, before they were understood by science. It suggests medieval viewers may have engaged with ancient artifacts in subtle ways, which turns the art into a hidden record of time.

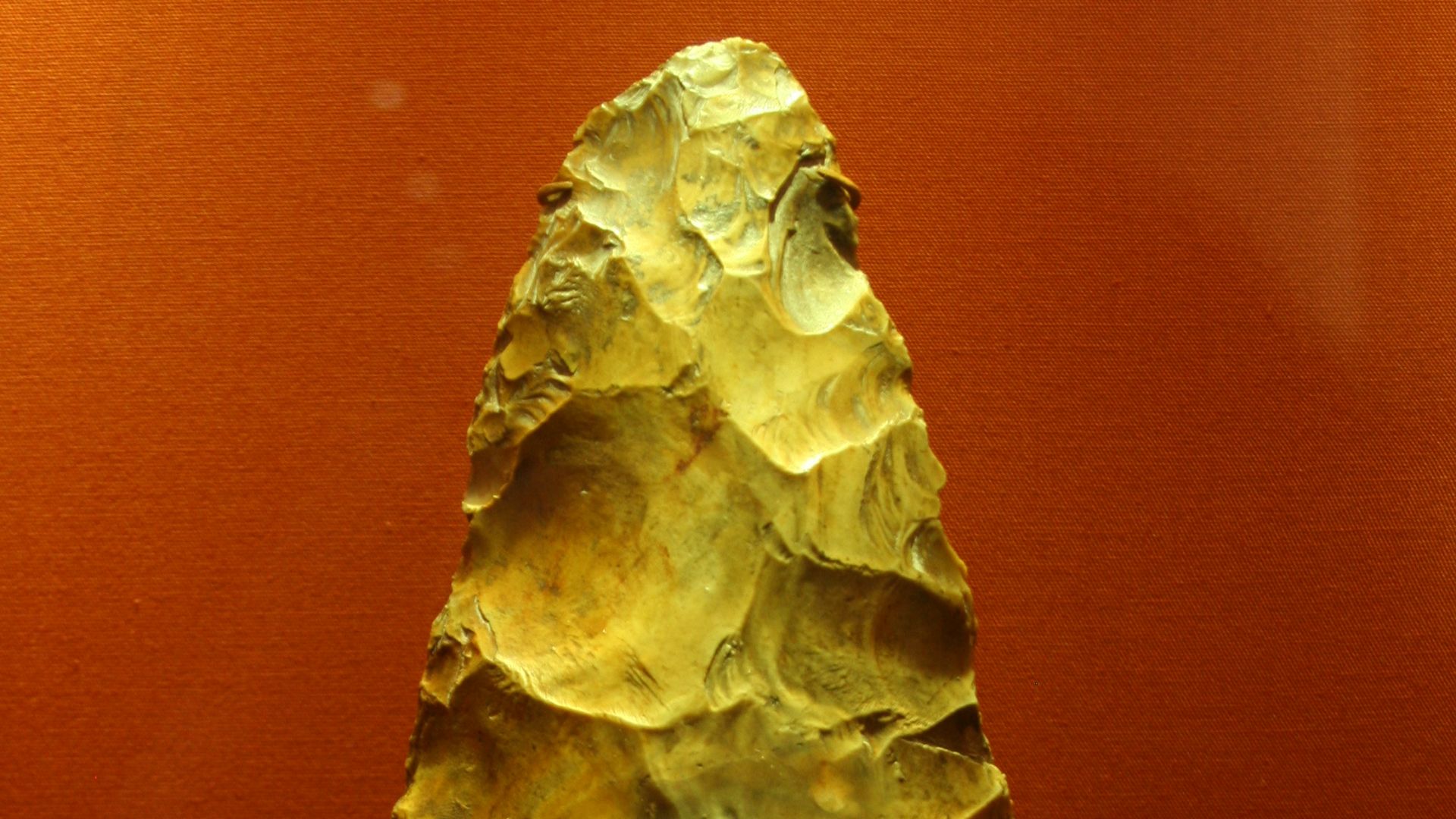

Stone Age Handaxes Defined

Handaxes are some of the earliest tools made by humans and are large, teardrop-shaped stones chipped on both sides to create sharp edges. Archaeologists now know they were crafted hundreds of thousands of years ago, making them far older than written history.

DocteurCosmos, Wikimedia Commons

DocteurCosmos, Wikimedia Commons

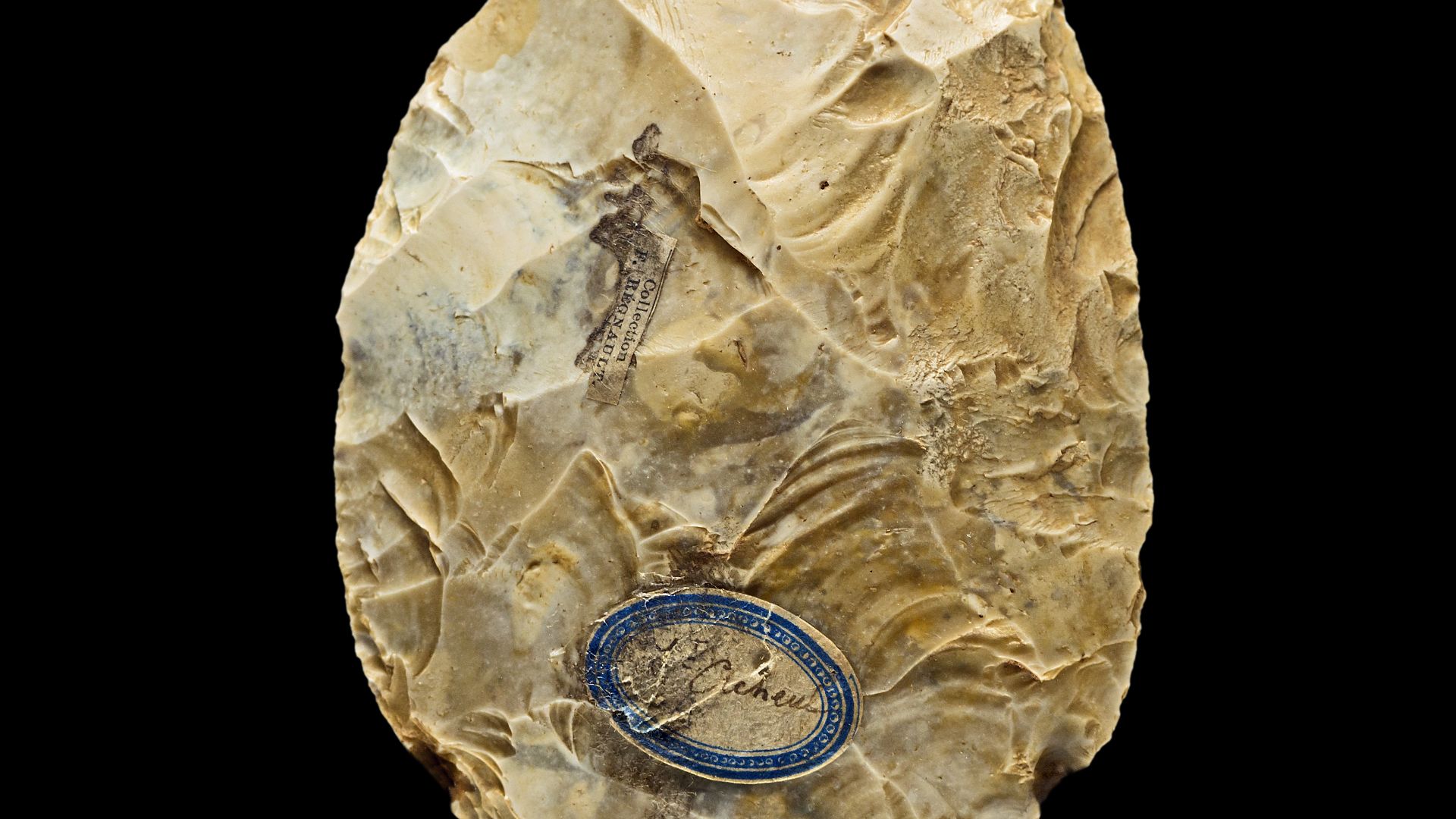

Notable Handaxe Finds

One striking example is the Excalibur handaxe from Atapuerca in Spain, a finely crafted red quartzite tool placed as a grave offering. Another is the Oxford handaxe, found near Wolvercote in England, often displayed as one of the finest Acheulean tools in Europe.

Acheulean Handaxe (Gran Dolina site TD10.1, Atapuerca, Spain) by Paula García Medrano

Acheulean Handaxe (Gran Dolina site TD10.1, Atapuerca, Spain) by Paula García Medrano

What Is An Acheulean Handaxe?

The Acheulean handaxe is one of humanity’s oldest and most widespread tools. First appearing about 1.7 million years ago, it was shaped from stone into a teardrop or oval form. These tools are found across Africa, Europe, and Asia, and mark a shared prehistoric technology.

Why The Acheulean Handaxe Matters

Unlike simple flakes, Acheulean handaxes show deliberate design with symmetry and balance. They reveal early human intelligence and planning. To see such a tool echoed in a fifteenth-century French painting is remarkable, bridging the Stone Age with Renaissance art.

Archaeodontosaurus, Wikimedia Commons

Archaeodontosaurus, Wikimedia Commons

Practical Uses Of Handaxes

These tools were multipurpose. People used them for cutting meat, shaping wood, and even breaking bones to reach marrow. A handaxe was not a weapon of war but a daily survival tool, passed down for countless generations in the Stone Age.

Hand axe - self sharpening - marlstone / limestone by freejutube

Hand axe - self sharpening - marlstone / limestone by freejutube

Handaxes In Folklore

When found in medieval Europe, handaxes were not recognized as ancient tools. Instead, they became part of folklore. Some believed they were made by elves or spirits, others thought they had magical powers, and many treated them as protective charms.

Malcolm Lidbury (aka Pinkpasty) , Wikimedia Commons

Malcolm Lidbury (aka Pinkpasty) , Wikimedia Commons

From Myth To Prehistory

It was not until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that scholars began questioning these legends. By the nineteenth century, scientists finally proved handaxes were prehistoric tools. This discovery reshaped human history, but it came long after Fouquet’s world had passed.

The Thunderstone Belief

Writers such as Pliny the Elder described ceraunia—stones believed to fall from the sky during storms. Medieval Europeans inherited this idea, calling them “thunderstones” and keeping them as charms against lightning. In reality, many of these so-called thunderstones were prehistoric handaxes, their true origin completely misunderstood.

Dimitris Kamaras from Athens, Greece, Wikimedia Commons

Dimitris Kamaras from Athens, Greece, Wikimedia Commons

Medieval Curiosity Collectors

Nobles and scholars sometimes gathered these objects into small collections. They sat alongside various fossils and shells. These “cabinets of wonders” were not kept for scientific purposes. However, they preserved artifacts that linked the natural world with the supernatural.

Cramyourspam, Wikimedia Commons

Cramyourspam, Wikimedia Commons

Could Fouquet Have Seen A Handaxe?

France is rich in prehistoric sites, and many handaxes turned up in fields and rivers. Fouquet could have seen one during his lifetime. Yet if he did, he would not have recognized it as an ancient weapon, only as a mysterious stone. Its meaning would depend entirely on imagination.

photo by Jurvetson (flickr), Wikimedia Commons

photo by Jurvetson (flickr), Wikimedia Commons

Visual Echoes In The Diptych

Some scholars note that shapes in the Diptych, especially the angular forms around the angels, resemble handaxes. Whether coincidence or intention, these echoes make us wonder if Fouquet drew on natural stone forms when creating his extraordinary vision of heaven.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Stone As A Symbol Of Permanence And Faith

Stone represents permanence and faith, enduring through centuries as a symbol of strength. Fouquet may have employed this meaning to show how the solid material world reflects deeper spiritual concepts of unbreakable faith.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

The Materiality Of Stone In Theology

Medieval thinkers also linked stone to the church itself. Cathedrals rose from stone, relics were guarded in jeweled containers of stone, and saints were remembered through the stones of their suffering. The audience at that time would have read these associations into Fouquet's imagery.

Ansgar Koreng, Wikimedia Commons

Ansgar Koreng, Wikimedia Commons

The Church's Control Over Knowledge

Medieval Christianity strictly controlled how people understood the natural world. Church doctrine determined which ideas could be explored and which were forbidden territory. Any object that appeared mysteriously ancient—like chipped stones found in fields—had to be explained within approved theological frameworks.

Jean Bourdichon, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Bourdichon, Wikimedia Commons

Natural Philosophy In The 15th Century

In Fouquet’s time, nature was studied through natural philosophy, always filtered through Christianity. Anything that seemed older than the biblical timeline—such as fossils or unusual stones—was never thought of as human-made. Instead, they were treated as divine curiosities or natural marvels beyond human history.

Limbourg brothers / Barthélemy d'Eyck, Wikimedia Commons

Limbourg brothers / Barthélemy d'Eyck, Wikimedia Commons

Transmission Of Ideas In The 15th Century

Understanding of the past spread slowly. Books were copied by hand, libraries were scarce, and knowledge moved through sermons, manuscripts, or conversation. In this setting, an artist like Fouquet might have encountered fragments of old ideas, yet the notion of ancient tools—like Stone Age handaxes—was unlikely to take clear shape.

Medieval scribe and illuminator, Wikimedia Commons

Medieval scribe and illuminator, Wikimedia Commons

The Diptych As A Meditation On Time

The two panels also contrast different views of time. Chevalier and Saint Stephen belong to the earthly present, while Mary and her angels exist in eternity. By setting them side by side, Fouquet invites viewers to reflect on history and timelessness together.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Did Fouquet Encode Prehistoric References?

Artists of the fifteenth century often layered hidden meanings into their works. Symbols could speak differently to educated viewers and ordinary worshippers. If Fouquet had encountered ancient stones, he may have woven them into his painting, not as science, but as mysterious sacred imagery.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Why We Ask The Question Today

The Diptych invites us to think about how medieval people engaged with objects they could not fully explain. Modern viewers see the possible handaxe and wonder: did Fouquet notice its unusual form, or have we uncovered meanings invisible to his contemporaries?

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Art Historians On Fouquet’s Symbolism

Modern art historians have long debated the painting’s unusual features. Some see the angels’ bright colors as symbolic of heavenly order; others stress their unsettling strangeness. Interpretations differ, but all agree that Fouquet was pushing beyond the conventions of his time.

The Diptych's Hidden Image

In addition to this mystery, in 2023, Monja Schunemann of Chemnitz University revealed a striking visual secret: when the two panels are folded, Etienne Chevalier appears close within the Virgin Mary’s mantle as she nurses the Christ child—an image known as a “lactatio”.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

The Diptych's Hidden Image (Cont.)

In the 15th century, the image of the Virgin nursing Christ symbolized divine nurture and the believer’s closeness to grace. By placing Chevalier within this private scene, Fouquet turned the Diptych into a personal devotion tool.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Folding As Intentional Design

Infrared and compositional studies confirm that Fouquet adjusted Chevalier’s and Saint Stephen’s heads precisely to align with the Madonna’s cloak when closed. This suggests the Diptych was deliberately designed to reveal a sacred private vision, accessible only when folded as originally intended.

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Fouquet, Wikimedia Commons

Survival And Alterations Across Centuries

However, over time, the Diptych was split apart. The left panel is now in Berlin, the right in Antwerp. Frames and settings were lost. Despite these changes, the surviving panels still carry the force of Fouquet’s vision.

Answering The Question

Fouquet could never have known a handaxe’s true prehistoric origin—the concept of deep time did not exist in the 15th century. The real question is ours: how do we interpret such echoes today, and what do they reveal about the layers of meaning in art?

Bristol City Council, Kurt Adams, 2010-07-06 13:59:25, Wikimedia Commons

Bristol City Council, Kurt Adams, 2010-07-06 13:59:25, Wikimedia Commons

Reflections On Art And Deep History

The Melun Diptych reminds us that art can carry mysteries across time. Whether or not handaxes shaped Fouquet’s vision, the question reveals how humans use imagination to bridge gaps in knowledge, turning unknown objects into symbols that speak far beyond their origins.

Northamptonshire County Council, Julie Cassidy, 2014-06-03 12:05:18, Wikimedia Commons

Northamptonshire County Council, Julie Cassidy, 2014-06-03 12:05:18, Wikimedia Commons