A Familiar Story, Now Questioned

For decades, scientists believed one clear story: a single early human species boldly left Africa and spread across the world. But new fossil evidence is quietly rewriting that narrative.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Scientists Mean By “Human Species”

Humans were never alone in the past. Over millions of years, several species lived at the same time, each with different brains and survival skills. Today’s humans are just the last surviving branch of a much larger, extinct family.

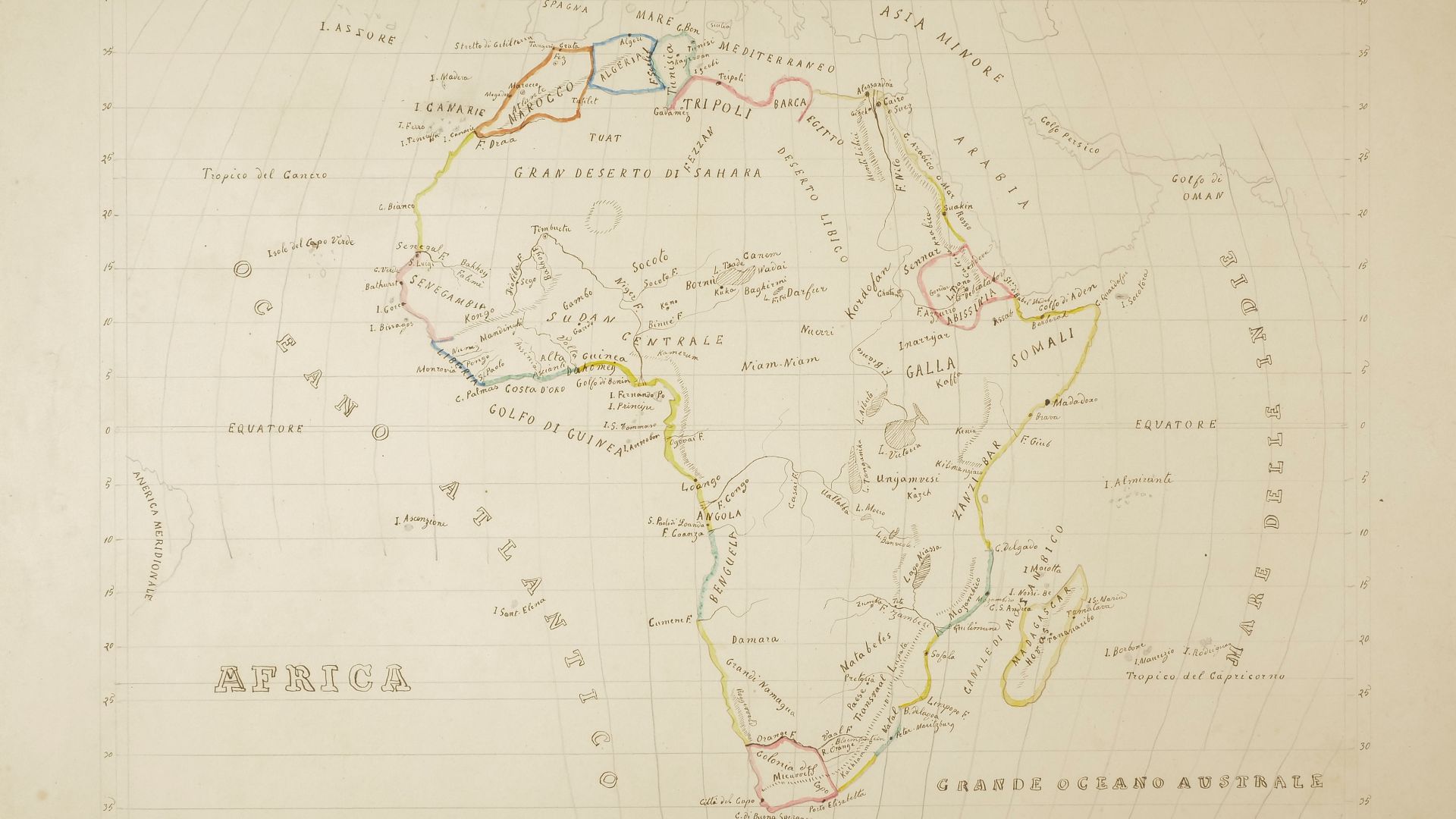

Why Africa Matters In Human Origins

Africa is where the earliest human ancestors evolved. The continent holds the oldest known fossils showing the gradual shift from ape-like ancestors to upright-walking humans. Because of this, scientists long assumed major human migrations must have started there first.

Giorgio Ermanno Anselmi (a cura), Wikimedia Commons

Giorgio Ermanno Anselmi (a cura), Wikimedia Commons

Who Was Homo Erectus?

Homo erectus lived nearly two million years ago and looked more human than earlier species. It had longer legs, a sturdier body, and a larger brain. Fossils reveal that it survived for an extraordinarily long time across multiple regions.

Jakub Halun, Wikimedia Commons

Jakub Halun, Wikimedia Commons

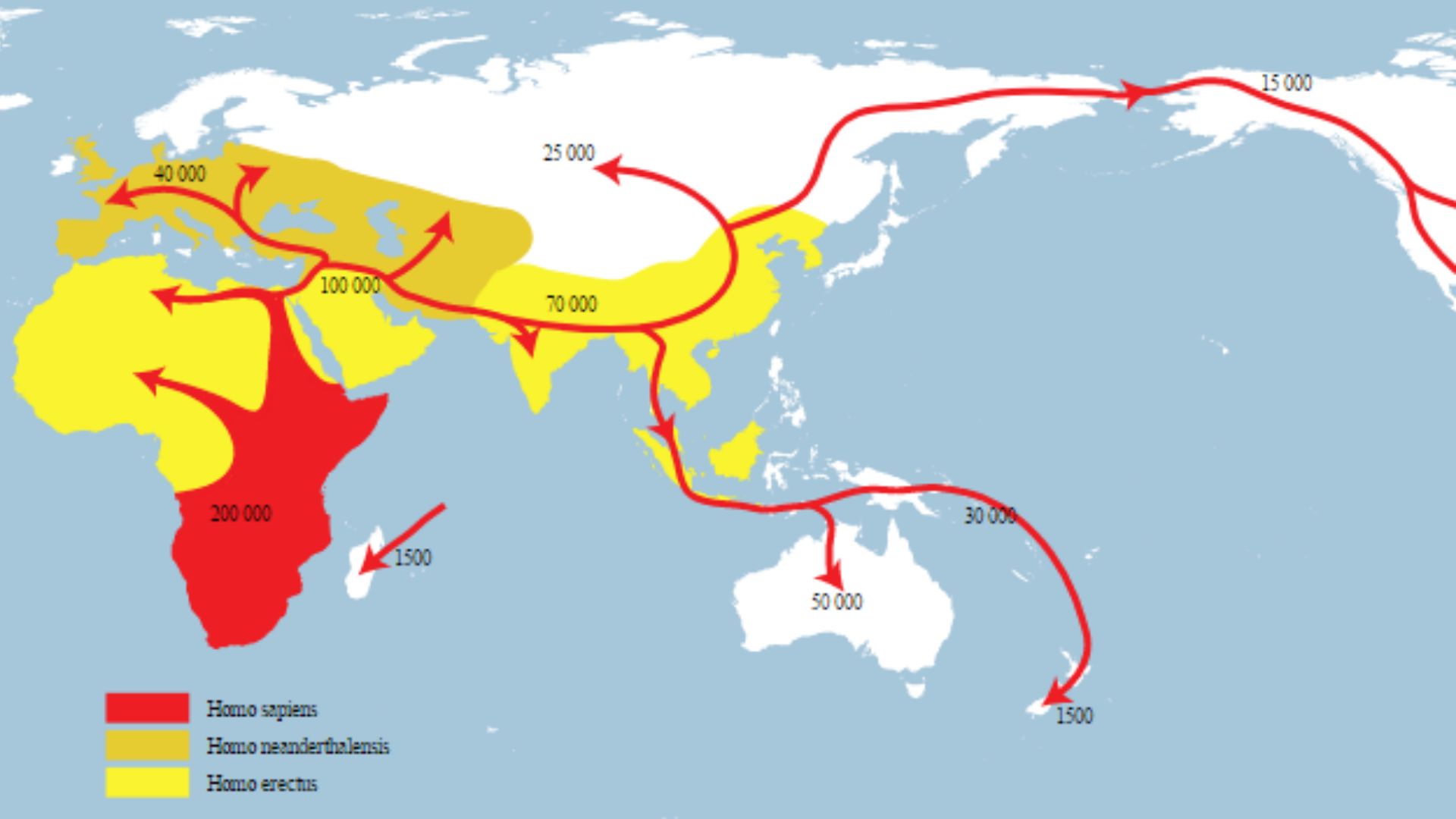

The Classic Migration Theory

The traditional theory dictated that around 2 million years ago, early hominins, possibly including multiple species, left Africa and spread into Asia and Europe. This moment was seen as a major evolutionary breakthrough. It was the first time humans successfully expanded beyond their birthplace.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Why Scientists Believed This For So Long

It made sense because earlier human species seemed poorly suited for travel. They had smaller bodies, smaller brains, and lived mainly in forests. Homo erectus, by contrast, appeared physically prepared to handle open terrain with changing climates and long journeys.

Early Fossils That Seemed To Confirm It

Some of the earliest human fossils found outside Africa, such as at Dmanisi, looked broadly similar to Homo erectus, but newer finds like Graunceanu in Romania, dated over 1.95 million years ago, reveal older and more primitive remains, challenging the idea that only one species made the journey.

Cicero Moraes et alii (Luca Bezzi, Nicola Carrara, Telmo Pievani), Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes et alii (Luca Bezzi, Nicola Carrara, Telmo Pievani), Wikimedia Commons

A Remote Site Changes Everything

That certainty began to fade after discoveries at Dmanisi, a remote fossil site in present-day Georgia. There, scientists uncovered human remains far outside Africa, dated to roughly 1.8 million years ago—a key early site long associated with the first human migration, though newer evidence suggests even older dispersals around 2 million years ago.

Georgian National Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Georgian National Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Fossils As Old As The Migration Itself

If humans were already living beyond Africa this early, it suggests the first journey outward wasn’t led by the most advanced species. Instead, simpler humans—with smaller brains and basic tools—may have wandered into new lands. They survived through the adaptability of their basic needs.

Jean-Pierre Dalbera from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Pierre Dalbera from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

Smaller Brains, Bigger Questions

Brain size was the biggest surprise. Some Dmanisi skulls had brain sizes as small as approximately 33.3 cubic inches—closer to those of much earlier humans than to those of classic Homo erectus. This confirmed that large brains were not required to survive beyond Africa at this early stage.

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Faces That Looked Strikingly Ancient

The skulls revealed flat noses with pronounced jaws, and facial shapes unlike classic Homo erectus. These features resembled those of earlier humans that were thought to have remained in Africa. It raises doubts about whether only one species or even one type made the journey outward.

Wolfgang Sauber, Wikimedia Commons

Wolfgang Sauber, Wikimedia Commons

Too Much Variation To Ignore

As more fossils were compared, scientists noticed striking differences between individuals found at the same site. Skull shapes, jaw sizes, and teeth varied far more than expected, which hinted these humans may not all belong to a single, clearly defined species.

Cicero Moraes et alii (Luca Bezzi, Nicola Carrara, Telmo Pievani), Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes et alii (Luca Bezzi, Nicola Carrara, Telmo Pievani), Wikimedia Commons

Early Humans At Dmanisi Had Diverse Body Sizes

The Dmanisi skeletons reveal noticeable differences in body size and build among individuals living together. Some were shorter and lighter, others stronger. This physical diversity shows early humans thrived with varied bodies while adapting successfully to the same environment.

Artist unknown, Wikimedia Commons

Artist unknown, Wikimedia Commons

Their Teeth Tell A Deeper Story

Teeth preserve exceptionally well, making them powerful records of diet and ancestry. A detailed dental analysis of the Rising Star Cave Homo Naledi specimens found a striking mix—some teeth resembled those of modern humans, while others resembled those of far older hominin species. It suggested overlapping evolutionary traits within a single population.

Cicero Moraes (Arc-Team) et alii, Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes (Arc-Team) et alii, Wikimedia Commons

All These Humans Lived Together

Careful dating revealed these individuals lived during the same short time period, not across thousands of years. That meant the physical differences weren’t evolutionary changes over time—but variation among people living side by side and trying to survive the changes.

Jakub Halun, Wikimedia Commons

Jakub Halun, Wikimedia Commons

No Fire, No Cooking

Unlike later human sites, Dmanisi shows no reliable evidence of controlled fire. These humans probably survived without cooking food or staying warm through fire. It challenges the belief that such abilities were essential for early migration into cooler regions.

Tools Came Straight From Africa

The stone tools discovered were Oldowan flakes, which match those used in Africa. Early humans carried familiar toolmaking knowledge with them as they moved. These reliable tools supported daily survival tasks and proved effective across new environments without requiring major changes.

Survival With Missing Teeth

At Dmanisi, one individual lost nearly all teeth yet lived for years afterward. Healed jawbone remodeling confirms long-term survival. Paleoanthropologists interpret this case as evidence of shared food and sustained social care among early humans before complex cultural systems emerged.

Henry Gilbert and Kathy Schick, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Gilbert and Kathy Schick, Wikimedia Commons

Living Among Dangerous Predators

Animal fossils show saber-toothed cats and other large carnivores shared the landscape. Early humans lived alongside these predators to gather meat when possible. Awareness probably helped them survive in an environment filled with powerful competing animals.

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Robert Knight, Wikimedia Commons

Eurasia Was Not Empty

These fossils show that Eurasia wasn’t a blank terrain awaiting one heroic arrival. Humans were already present locally. This suggests early expansion happened in stages, with small groups surviving and spreading gradually rather than through one dramatic migration event.

naturalearthdata.com, offered to the Public Domain per Terms of Use, Wikimedia Commons

naturalearthdata.com, offered to the Public Domain per Terms of Use, Wikimedia Commons

Thriving In An Unstable Climate

Environmental evidence reveals changing climates across the region. Early humans responded by using a wide range of food sources and adjusting their behavior as conditions shifted. Their ability to remain flexible and responsive supported long-term survival as they expanded into new environments.

Moving Along Natural Pathways

Geography guided early humans along valleys, rivers, and grasslands linking Africa to Eurasia. Groups may have moved in small stages while tracking water and animals. Over time, these steady movements carried people across regions and expanded humanity’s presence beyond its original homeland.

Javier Puig Ochoa, Wikimedia Commons

Javier Puig Ochoa, Wikimedia Commons

Where Homo Erectus Still Fits

Fossils show that Homo erectus or closely related forms spread farther and lasted longer than many early hominins, reaching parts of Asia to survive for over a million years. Their success came later, suggesting they were among the most enduring, though debates continue on species distinctions.

Questions Scientists Are Still Chasing

Researchers continue debating how many human groups left Africa early, how closely they were related, and whether they mixed. New fossils and improved dating methods may clarify these relationships, but for now, early human migration remains an open and active scientific puzzle.

Yulia Kolosova, Wikimedia Commons

Yulia Kolosova, Wikimedia Commons

Why This Discovery Truly Matters

Understanding who left Africa first reshapes how we define success in human evolution. Survival didn’t depend on being the strongest or smartest. It depended on coping with uncertainty—showing that human history was shaped by persistence long before progress or innovation.

Ryan Schwark, Wikimedia Commons

Ryan Schwark, Wikimedia Commons