Engineering So Good The Spanish Had To Have It

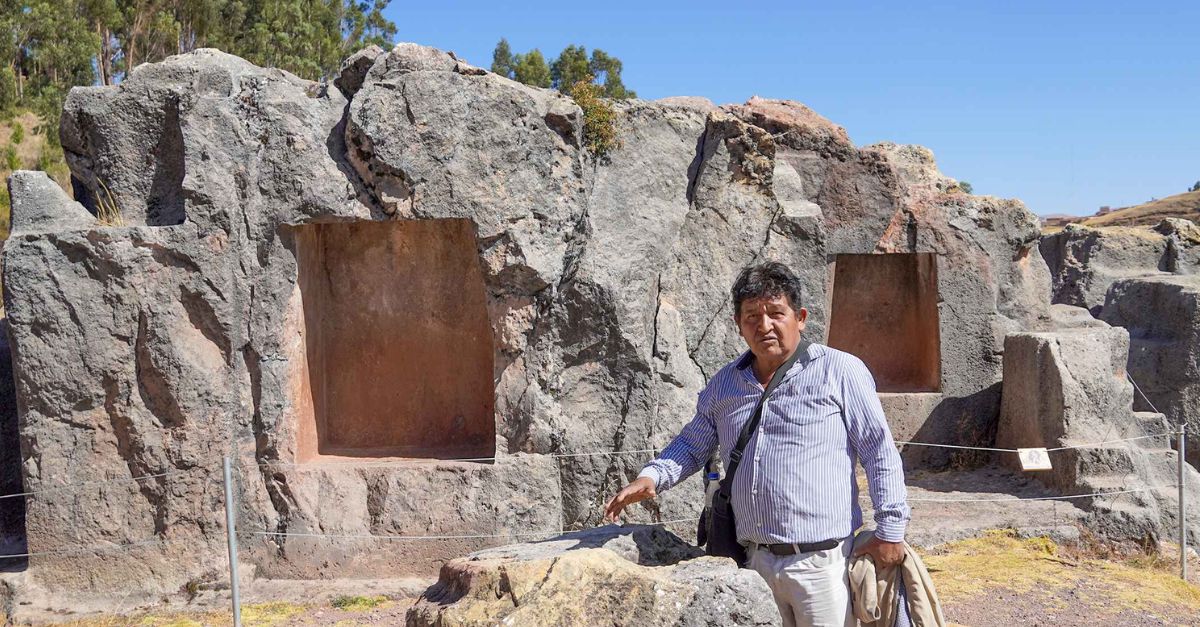

High above Cusco, colossal stones fit together so seamlessly you couldn’t slip a blade between them. This is Sacsayhuaman, the Inca fortress that defies time and explanation. And guess what? Spaniards wanted a piece of it.

Introducing Sacsayhuaman

Sacsayhuaman served as both a mighty fortress guarding Cusco and a ceremonial hub. But let’s just take a few (or many) steps back. How did it all unfold? Who built it? And how were the Spanish involved? To fully grasp this, we must go back to the very beginning.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Starting With The Origins Of The Killke Culture

Before the Incas, the Killke settled Cusco (900–1200 AD), leaving stone foundations, pottery, and walls. These remains show construction began centuries earlier. Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui, in the 15th century, expanded and formalized architecture like Sacsayhuaman, but he built upon foundations laid long before his reign.

Incialemantos, Wikimedia Commons

Incialemantos, Wikimedia Commons

Pachacuti Had A Vision For A Fortress

Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui was the transformative ninth ruler of the Inca Empire (reigned 1438–1471). He was credited with turning a modest kingdom centered in Cusco into a vast imperial power stretching from Ecuador to northern Chile. Pachacuti meant “the turn of the world” and yupanki “honorable lord” in Quechua.

Cuzco School, Wikimedia Commons

Cuzco School, Wikimedia Commons

Pachacuti Was A Big Deal

This man led and orchestrated sweeping reforms and conquests, which included reorganizing governance, expanding infrastructure, and commissioning the iconic site of Machu Picchu. Pachacuti also elevated the cult of Inti, the sun god, and established the Inti Raymi festival to mark the Andean new year.

Cyntia Motta, Wikimedia Commons

Cyntia Motta, Wikimedia Commons

Selecting The Hilltop Site Overlooking The Sacred City

According to Inca oral tradition and chroniclers like Pedro Cieza de Leon, Pachacuti envisioned Cusco as a puma-shaped city, with Sacsayhuaman forming the "head" on the high plateau to the north. Commanding a panoramic view of Cusco, the chosen hilltop offered tactical superiority.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Location Really Mattered

Location mattered: defenders could anticipate threats while priests observed the heavens. The high position fused military strategy with cosmic symbolism, and this turned the site into a masterpiece of practicality and spirituality. After location selection came material sourcing.

Martin St-Amant (S23678), Wikimedia Commons

Martin St-Amant (S23678), Wikimedia Commons

Quarrying Limestone Blocks Came From Nearby Sources

If you look at the structure today, you’ll be amazed at how these massive rocks came to be. They resemble typical drywall stones, but on a much larger scale. The estimated weight was 128 to 200 tonnes each. These stone blocks were quarried from Rumicolca, about 22 miles away.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Transporting 200-Ton Stones Without The Wheel

Moving stones over 100 tons tested every limit. Without wheels or animals, 6,000 laborers hauled blocks using leather and cabuya ropes. Overseers timed the effort with chants, guiding stones across hills. Oral lore even speaks of a colossal stone abandoned mid-journey, still visible today.

The Role Of The Mita Labor System In Construction

At least 20,000 workers rotated under the mita system to bring provisions and build huts near the site. Tasks were divided: quarrymen, haulers, foundation diggers, and woodcutters. Rotations meant no group worked endlessly. Collective labor turned vision into enduring stone.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Bronze Tools And Hematite Hammers In Stone Shaping

The artisans also had to get the shape right. So, the Incas shaped Sacsayhuaman’s massive stones using bronze chisels, stone hammers, and wooden wedges soaked in water to split the rock. Without iron tools, they relied on pecking and precision to fit andesite and limestone blocks tightly.

All Hands Were On Deck

About 4,000 specialists were dedicated solely to quarrying. Craftsmen carved grooves, polished joints, and achieved fits so exact that a coin couldn’t slip through. The artistry stunned Spanish chroniclers, who doubted human strength could achieve such mastery.

Filipe Fortes, Wikimedia Commons

Filipe Fortes, Wikimedia Commons

The Zigzag Walls Symbolizing Lightning

Walls stretched 330 paces in length and 200 in width, rising in zigzag tiers resembling lightning bolts. Some stones measured over twelve feet wide and twenty feet long. These walls weren’t only defensive—they embodied Viracocha’s cosmic energy, to bind warfare and worship into stone.

User:Colegota, Wikimedia Commons

User:Colegota, Wikimedia Commons

Earthquake-Resistant Engineering In Design

Foundations were carved into living rock to create a base so solid that chroniclers claimed it would “endure as long as the world itself”. Joints fit so tightly, and the inward-leaning walls absorbed seismic shock, allowing the structure to survive centuries of Andean earthquakes.

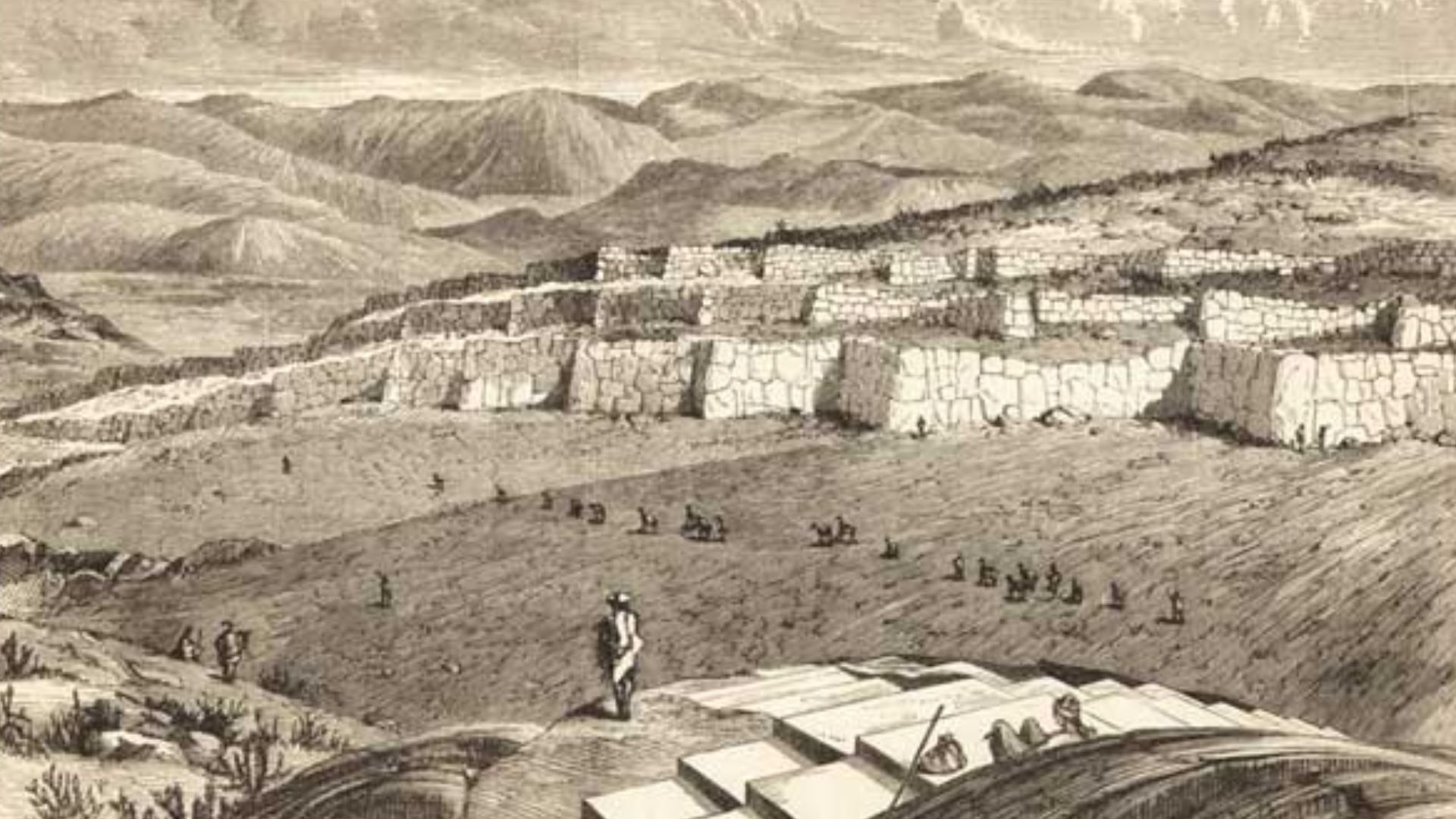

Building Three Towering Structures On The Hill

The fortress crowned Cusco with three towers. Chroniclers described spiral stairways and multiple levels, with some chambers underground. Their dazzling scale made them defensive watchtowers and royal storehouses. This lot crowned the fortress with grandeur that towered above the lion city.

Integration Into Cusco’s Puma-Shaped City Layout

Cusco was designed in the form of a puma, an animal sacred in Andean cosmology. Later traditions and interpretations credit Pachacuti with visionary planning. Sacsayhuaman completed the puma’s form, its fortress-head commanding the valleys—an urban design uniting landscape, empire, and celestial beliefs.

McKay Savage from London, UK, Wikimedia Commons

McKay Savage from London, UK, Wikimedia Commons

The Fortress As The “Head” Of The Puma

With Sacsayhuaman crowning Cusco, the puma gained a head of stone. Towers formed its ears, zigzag walls its jagged teeth. Standing there today, you see ruins—but also a symbolic predator frozen in architecture. This was once someone’s vision, and it finally came to life.

Luis Padilla, Wikimedia Commons

Luis Padilla, Wikimedia Commons

Defensive Strategy During The Inca Empire

The fortress combined terraces, gates, and commanding walls into a defense system admired by the Spanish who came later. Entrances overlapped, so one wall commanded another. Archers and stone throwers could trap enemies in any deadly attack, and the attackers would never see it coming.

The Major Features Of Sacsayhuaman

The most iconic feature of Sacsayhuaman is its zigzagging triple-tiered walls. At the heart of the fortress stood Muyuq Marka, a circular tower believed to serve ceremonial or astronomical functions. Though only its base remains today, chroniclers described it as a multi-level structure with water channels and sacred significance.

Nearby…

Sallaqmarca and Paucamarca—two rectangular towers—provided surveillance and strategic defense, forming a triadic system that guarded the complex’s highest points. Carved into the bedrock was the Inca Throne, a series of polished stone seats where the emperor may have presided over rituals or military reviews.

Mx._Granger, Wikimedia Commons

Mx._Granger, Wikimedia Commons

There Were More Structures

Adjacent to the Throne was the Rodadero, also known as Suchuna, a smooth, natural outcrop used for ceremonial sliding and possibly water flow; its playful surface still attracts visitors today. Among the most mysterious features were the tunnels, notably the Chinkana Chica, the “small chincana”.

Recent Discoveries Point To The Tunnel’s Existence

Archaeologists like Jorge Calero and Mildred Fernandez have used ground-penetrating radar and acoustic testing to map a network of tunnels stretching about 1.09 miles (approximately 1,750 meters). These tunnels feature stone-lined walls and multiple branches leading to places like Callispuquio, Muyuq Marka, and San Cristobal.

The Chinkana Chica Tunnel Is Open To The Public Today

Accessible to the public, Chinkana Chica offers a tactile glimpse into the legends of underground labyrinths. In contrast, the other tunnel, the Chinkana Grande, remains sealed off, rumored to stretch beneath Cusco and connect sacred sites like Qorikancha. This one was closed for safety reasons.

Construction Went On For Decades

Sacsayhuaman was largely completed in the mid-to-late 15th century, during the reigns of Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui (1438–1471) and his son Tupac Inca Yupanqui. Construction likely spanned decades. And the final touches and expansions may have continued into the reign of Huayna Capac (1493–1527), just before the Spanish arrived.

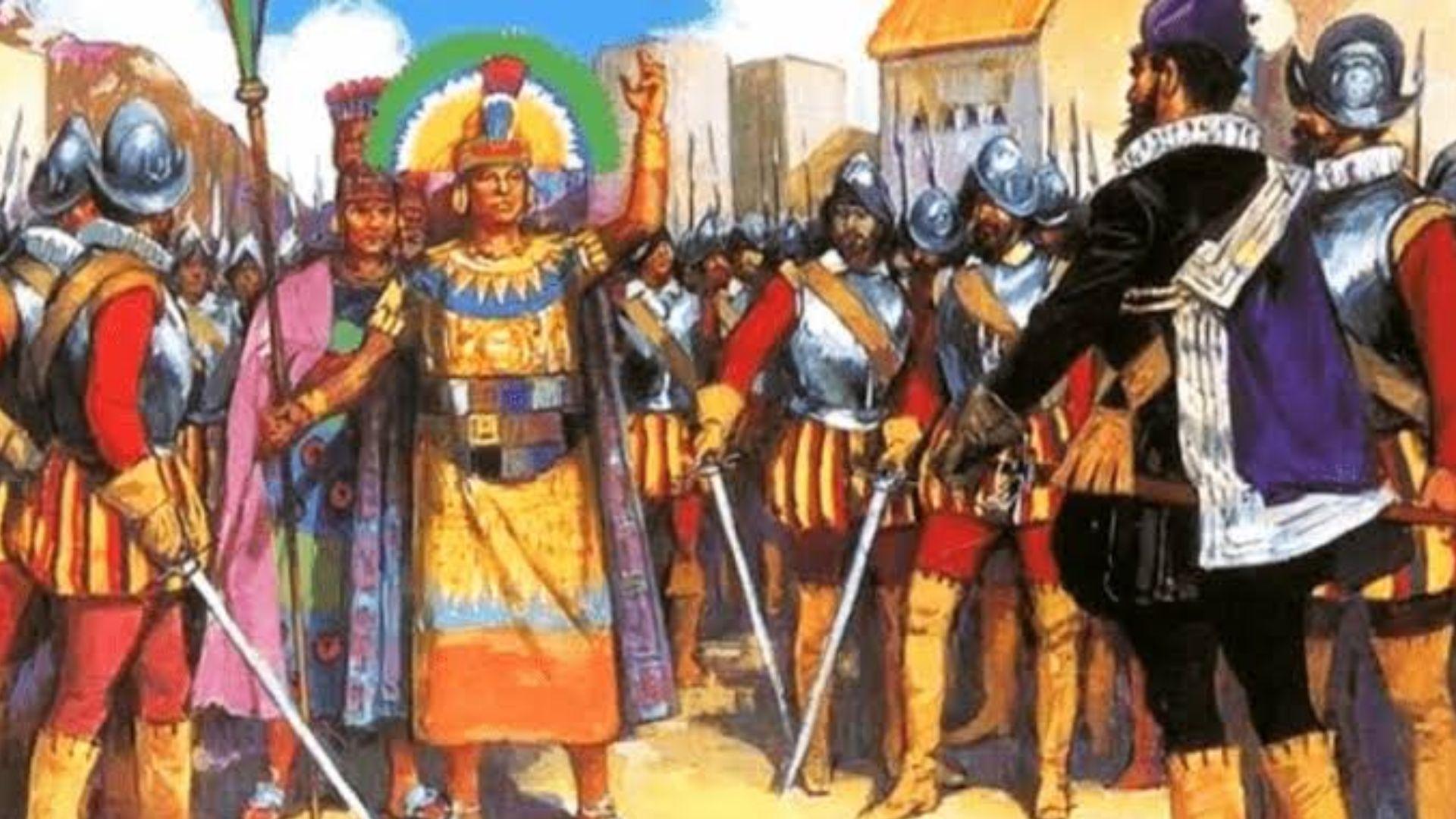

The Spanish Arrival

The Spanish, led by Francisco Pizarro, first made contact with the Inca Empire in 1526 during exploratory voyages along the Pacific coast. However, their formal arrival and conquest began in 1532, when Pizarro landed in northern Peru with a small force of around 168 men.

Julio Vila y Prades, Wikimedia Commons

Julio Vila y Prades, Wikimedia Commons

The Inca Empire Wasn’t Doing So Well Then

At that time, the Inca Empire was weakened by a brutal civil war between brothers Atahualpa and Huascar, which made it vulnerable to external threats. So, Pizarro seized this opportunity, capturing Atahualpa at Cajamarca in November 1532. By 1533, the Spanish had marched into Cusco and began consolidating their rule.

How They Consolidated Their Rule

The Spanish consolidated their rule over the Inca Empire through a multifaceted strategy that combined military dominance, political manipulation, cultural imposition, and economic control. After executing Atahualpa in 1533, they installed puppet rulers like Tupac Hualpa and Manco Inca to legitimize their presence while undermining native authority.

Juan Lepiani, Wikimedia Commons

Juan Lepiani, Wikimedia Commons

They Completely Took Over

They repurposed the temples and palaces into colonial institutions, often building churches on top of sacred Inca sites to assert their religious and symbolic dominance. To maintain control, they forged alliances with rival Andean groups—such as the Huancas and Chachapoyas—who had grievances against the Inca elite.

Millais, John Everett (Sir) (1829 - 1896) – artist Details on Google Art Project, Wikimedia Commons

Millais, John Everett (Sir) (1829 - 1896) – artist Details on Google Art Project, Wikimedia Commons

The Siege Of Cusco Started In 1536

A volatile mix of betrayal, oppression, and strategic opportunity triggered the Siege of Cusco in 1536. After being installed as a puppet ruler by the Spanish, Manco initially cooperated in the hope that the Spanish would help preserve some autonomy. But…

Francisco López de Gómara, Wikimedia Commons

Francisco López de Gómara, Wikimedia Commons

It Did Not Pan Out As He Had Hoped Because…

The conquistadors—especially the Pizarro brothers—humiliated and imprisoned him, treating him more like a servant than a sovereign. Once released under the pretense of organizing religious ceremonies, Manco escaped to the Yucay Valley, where he rallied tens of thousands of warriors from across the Andes.

Margaret Duncan Coxhead, Wikimedia Commons

Margaret Duncan Coxhead, Wikimedia Commons

The Timing Was Critical

Why? Because the Spanish were still relatively few in number, and their grip on the empire was fragile. Manco saw a chance to reclaim Cusco. On May 6, 1536, his forces launched a coordinated assault that targeted Sacsayhuaman first to gain the high ground.

Cusco School, Wikimedia Commons

Cusco School, Wikimedia Commons

Betrayal Was The Fuel To This Fire

The siege was a symbolic uprising against colonial domination, sparked by personal betrayal and fueled by widespread indigenous resentment. What followed was a long siege, one of the last great military efforts by the Incas to resist colonial domination.

How The Great Siege Of Cusco Panned Out

All the warriors Manco Inca had assembled stormed Sacsayhuaman, and they briefly recaptured the fortress by hurling flaming projectiles at Spanish positions. This battle, unexpected by many, echoed across the Andes.

The Initial Success

Inca forces quickly overwhelmed the outskirts and recaptured Sacsayhuaman. How did they do that? They bombarded Spanish positions with flaming projectiles and cut off supply routes. As you know, without supplies, one stands down, right? Wrong!

The Spanish Retaliated

Led by Hernando and Gonzalo Pizarro, the conquistadors mounted a brutal counterattack. This counterattack was successful because they retook Sacsayhuaman after fierce fighting, which also included hand-to-hand combat and scaling walls under fire.

Margaret Duncan Coxhead, Wikimedia Commons

Margaret Duncan Coxhead, Wikimedia Commons

Prolonged Stalemate

Most sieges are short, but not this one. This one lasted nearly 10 months, with the Spanish trapped and sending desperate pleas for reinforcements. Manco’s forces used guerrilla tactics and even trained with captured Spanish weapons to get what belonged to them.

Collapse And Withdrawal

By March 1537, facing superior cavalry and dwindling supplies, Manco withdrew to Ollantaytambo, then later to Vilcabamba, where he established a Neo-Inca state that resisted Spanish rule for decades after. After the collapse of the Siege of Cusco in 1537, Spanish rule not only remained but deepened.

Mx._Granger, Wikimedia Commons

Mx._Granger, Wikimedia Commons

The Failed Uprising Marked A Turning Point

The Incas lost their last real chance to reclaim the imperial capital, and the Spanish began transforming Cusco into the administrative and religious center of their new colony. What follows is what the Spanish did after the siege.

They Reinforced Control

The Spanish received reinforcements from across the Americas, and this solidified their military presence in Peru. They also repurposed Inca temples and palaces—most famously building the Church of Santo Domingo atop the sacred Qorikancha—to assert religious and cultural dominance.

fractales222, Wikimedia Commons

fractales222, Wikimedia Commons

Political Consolidation

In 1542, Spain established the Viceroyalty of Peru, formalizing colonial governance and placing Cusco under direct royal administration. Still, even after Manco Inca had retreated to Vilcabamba and founded a Neo-Inca state, the Spanish waged campaigns to isolate and eventually destroy it, culminating in the execution of Tupac Amaru in 1572.

They Even Dismantled Stones For Colonial Buildings In Cusco

This is one of the most striking examples of cultural repurposing in colonial history. After the Spanish suppressed Manco Inca’s rebellion and secured control of Cusco, they began dismantling parts of Sacsayhuaman and other Inca structures to reuse the finely cut stones in their own colonial buildings.

What Happened To The Stones

Sacsayhuaman became a quarry because the Spanish authorities treated the fortress as a public source of building material. The precision-cut blocks were often inserted into colonial buildings without the same engineering finesse, and this created a visual patchwork of styles.

The Left The Megaliths Because They Were Too Heavy To Move

The heavier stones were too large for even the most determined Spaniards to repurpose. They abandoned them instead. These massive blocks now define the fortress’s silhouette, proof that Inca ingenuity produced works that even conquest could not erase.

Ongoing Excavations Expanding Historical Knowledge

Today, archaeologists continue to unearth hidden chambers, foundations, and artifacts. Every season adds new context and deepens understanding of Inca society. Imagine soil revealing secrets after centuries—it proves Sacsayhuaman isn’t frozen in time, but an active puzzle still giving up its stories.

Preservation Efforts Against Tourism And Erosion

Heavy tourism and natural erosion threaten the fortress’s longevity. Protective measures include restricted access and careful restoration. Visitors are even urged to tread lightly. Safeguarding Sacsayhuaman ensures future generations also marvel at its grandeur, not just read about its past.

Sacsayhuaman Today: Living Heritage Of The Andes

Sacsayhuaman is alive with rituals, festivals, and research. It bridges past and present, Inca ingenuity and modern curiosity. When you wander its stones, you feel a sense of continuity, a living heritage still pulsing at the heart of the Andes. And now, you know how history unfolded here.