New Zealand's Māori People

The Māori people of New Zealand have a long, proud heritage and culture. They are the second-largest cultural group in New Zealand, after European New Zealanders, and despite all efforts by colonial powers, the Māori remain a strong part of New Zealand's history. Let's explore the history of the Māori and where they are today.

A Disputed Arrival Timeline

According to carbon dating, the Māori first came to New Zealand's North Island between 1250 AD and 1275 AD, likely by canoe voyage from Polynesia. However, some suggest that the Māori were present on the North Island for the volcanic eruption of Mount Tarawera in 1315 AD.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Origins Of The Māori

No credible evidence exists that anyone else settled in New Zealand before the Māori did. Studies of Māori genealogy suggest that their ancestors stretch back 5,000 years to the Indigenous people of Taiwan, the Austronesians. It's thought that the Māori are a part of Polynesians that settled in countries like Tonga, Samoa, Hawai'i, Tahiti, and (eventually) New Zealand.

Josiah Martin decd 1916., Wikimedia Commons

Josiah Martin decd 1916., Wikimedia Commons

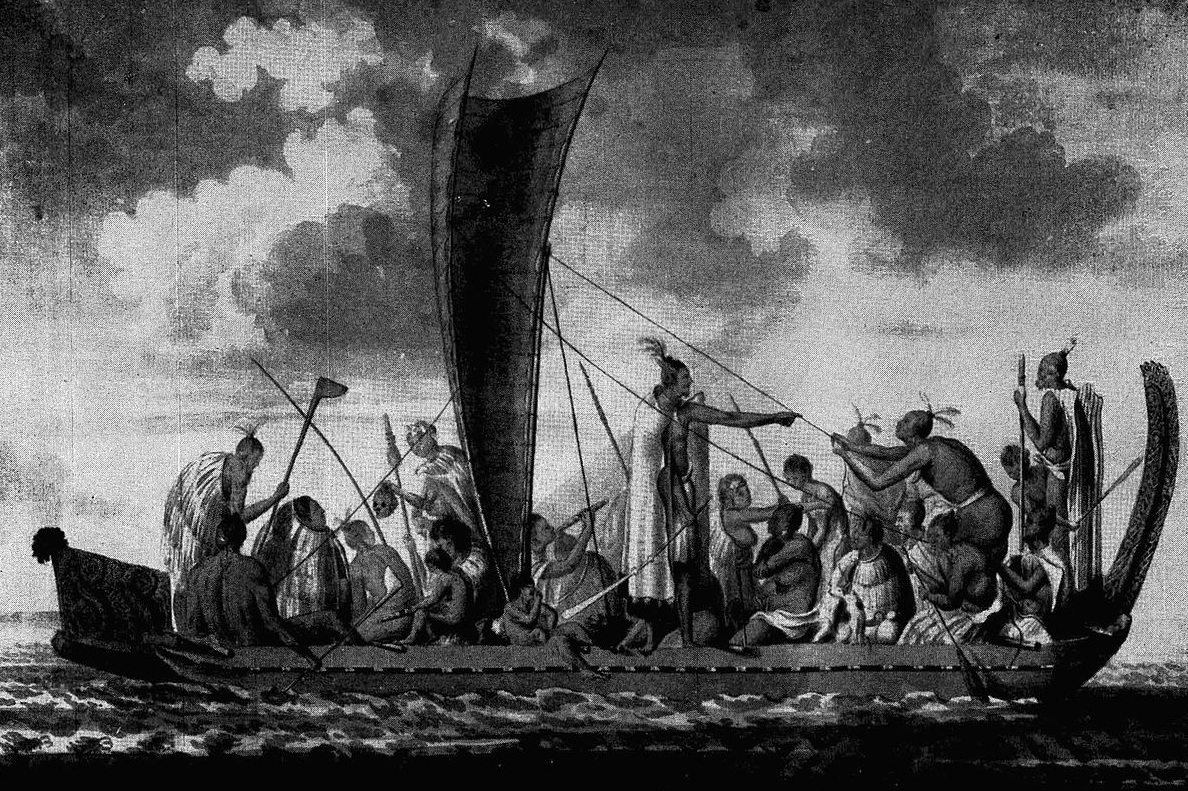

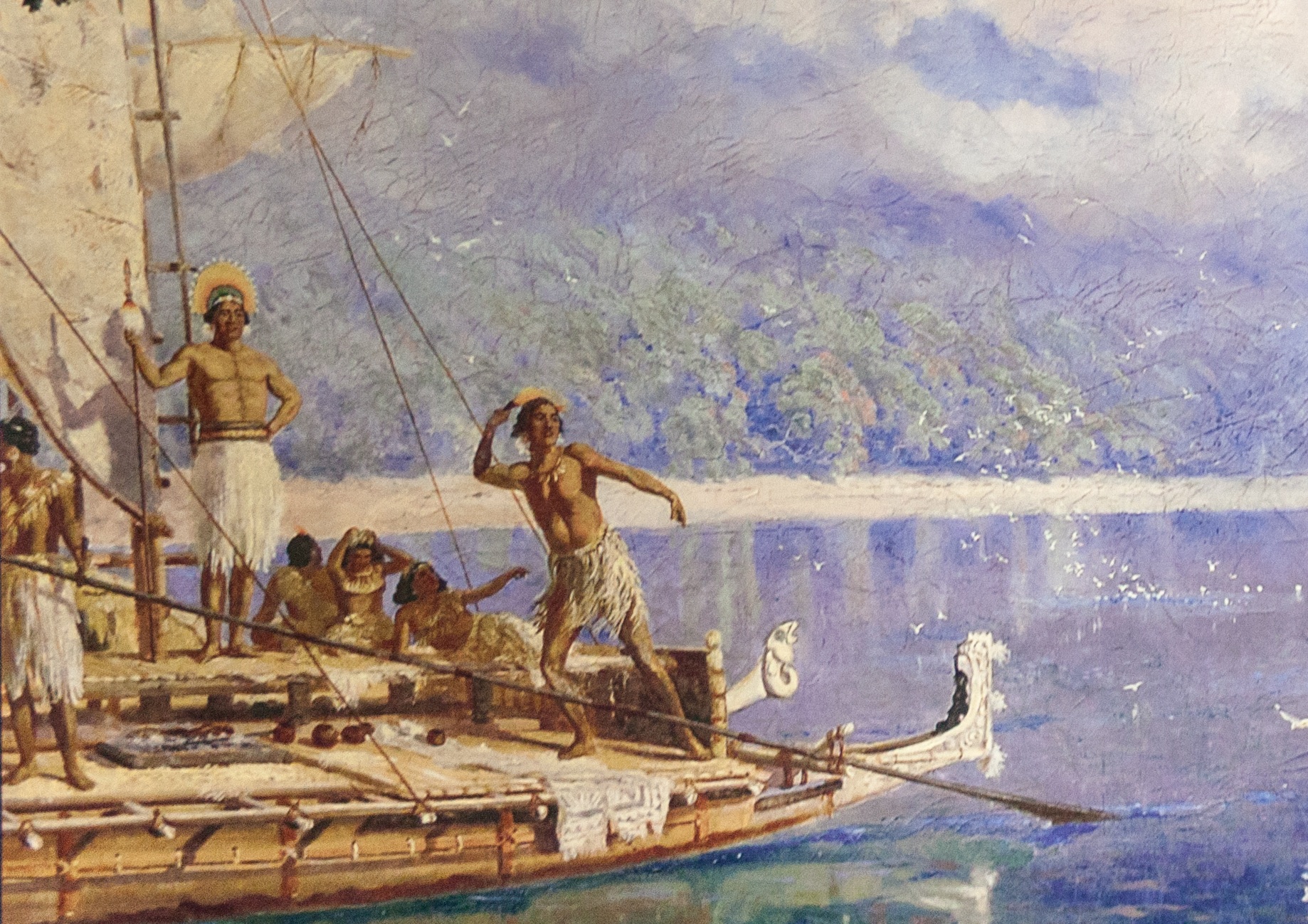

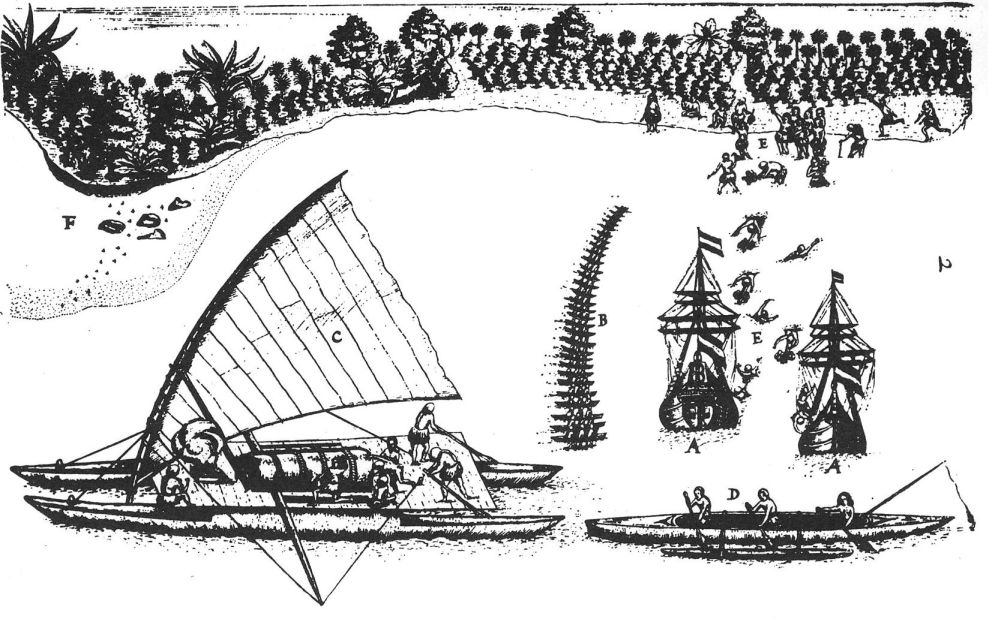

A Voyage From Polynesia

Māori oral tradition and carbon dating put their arrival around 1350 AD as part of a planned mass migration from other parts of Polynesia, to the North Island of New Zealand. These voyages were undertaken in "waka," large ocean-going twin-hulled canoes.

Isaack Gilsemans, Wikimedia Commons

Isaack Gilsemans, Wikimedia Commons

The Legend Of Ui-Te-Rangiora

According to the New Zealand ethnologist Stephen Percy Smith (who translated the Polynesian language of Rarotongan into English), legendary Polynesian explorer Ui-Te-Rangiora may have paddled his canoe as far south as Antarctica in 650 AD, reaching "a place of bitter cold where rock-like structures rose from a solid sea".

A. Buchan, S. Parkinson or J. F. Miller, Wikimedia Commons

A. Buchan, S. Parkinson or J. F. Miller, Wikimedia Commons

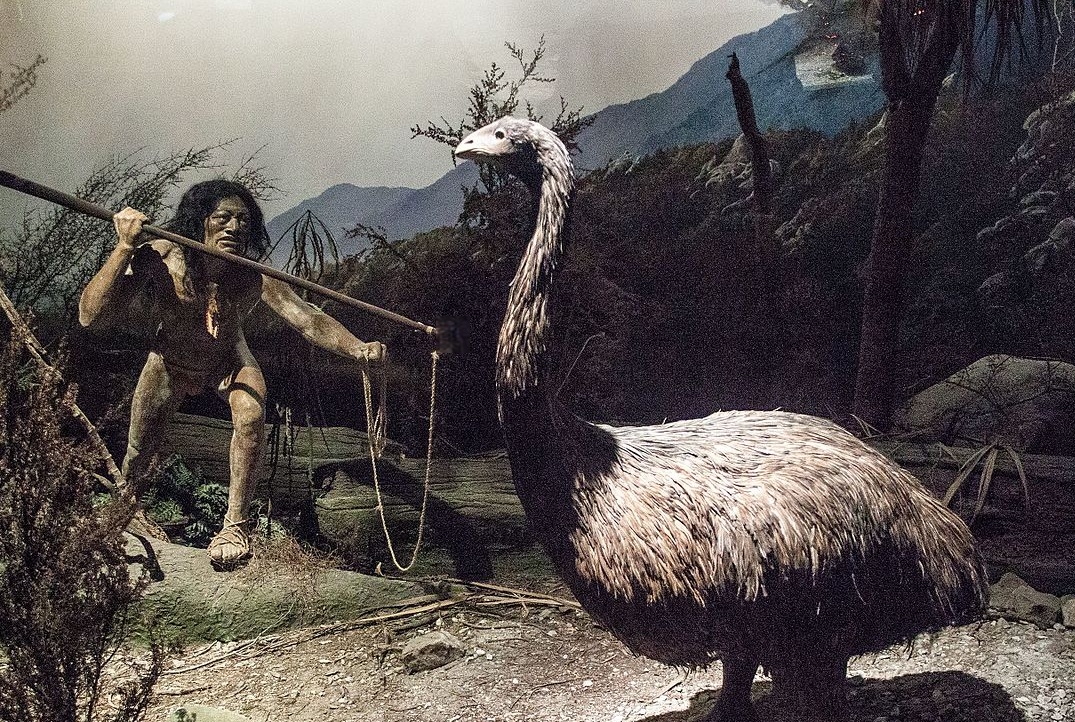

The Moahunter Period

The Moahunter is the earliest studied period of Māori history dating from arrival on the North Island to about 1500 AD. This period included the study of how the Māori lived. The Moahunter period is mostly associated with the creation of classic Māori jewellery like reel pendants. It is followed by the Classic period, which began in 1500 AD.

Kenneth Watkins, Wikimedia Commons

Kenneth Watkins, Wikimedia Commons

An Early Māori Diet

Studies of the Moahunter period conclude that the early Māori settlers to New Zealand ate an almost exclusively bird-based diet, specifically the now-extinct Moa, a flightless bird that bears close skeletal resemblance to the ostrich or emu. Other large birds and fur seals were also included in the Māori diet.

Extinct Within 100 Years Of Contact

Unfortunately for the poor Moa, they became extinct within 100 years of human contact. The extinction of the Moa gave way to the Classic period of Māori habitation in New Zealand.

Hutchinson, H. N.; Knight, Charles Robert; Smit, Joseph; Woodward, Alice B.,Wikimedia Commons

Hutchinson, H. N.; Knight, Charles Robert; Smit, Joseph; Woodward, Alice B.,Wikimedia Commons

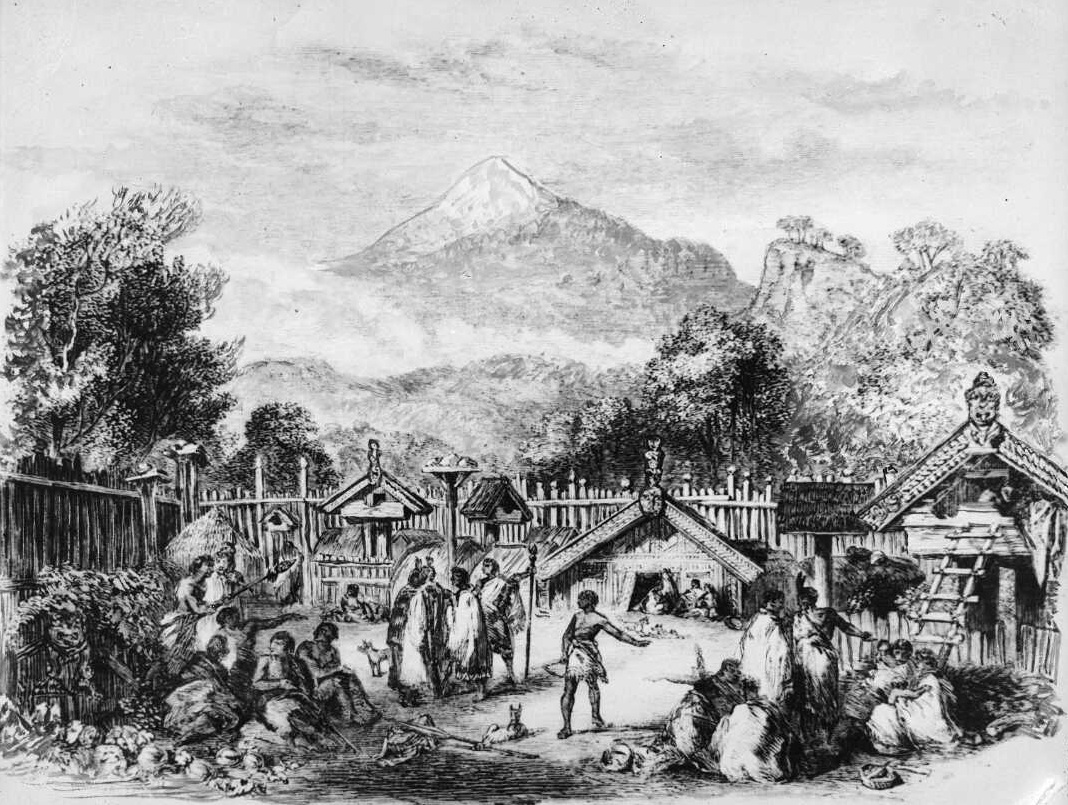

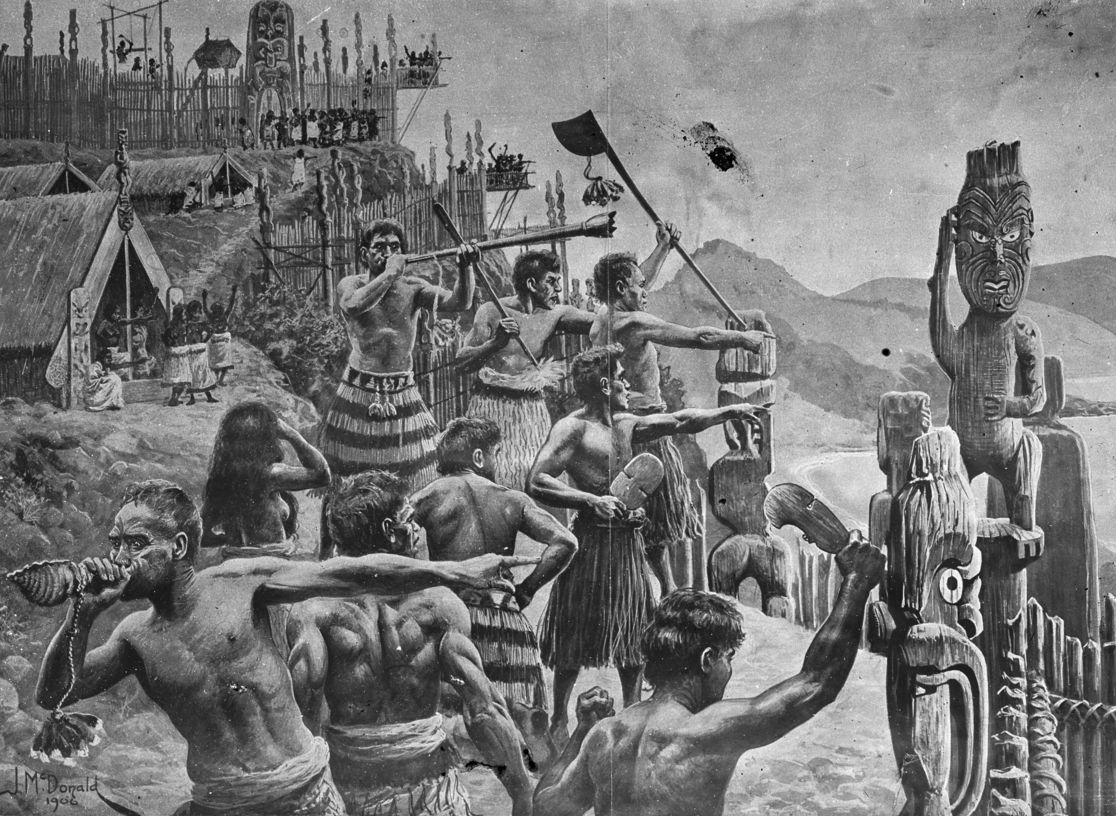

The Classic Period Begins

The period of Māori history known as the Classic period began after 1500 AD, this is when the Māori began developing warfare skills and finely carved greenstone spears as weapons. The Māori also started carving war canoes, and began developing fortified villages and settlement areas that propagated farming and contained food sources.

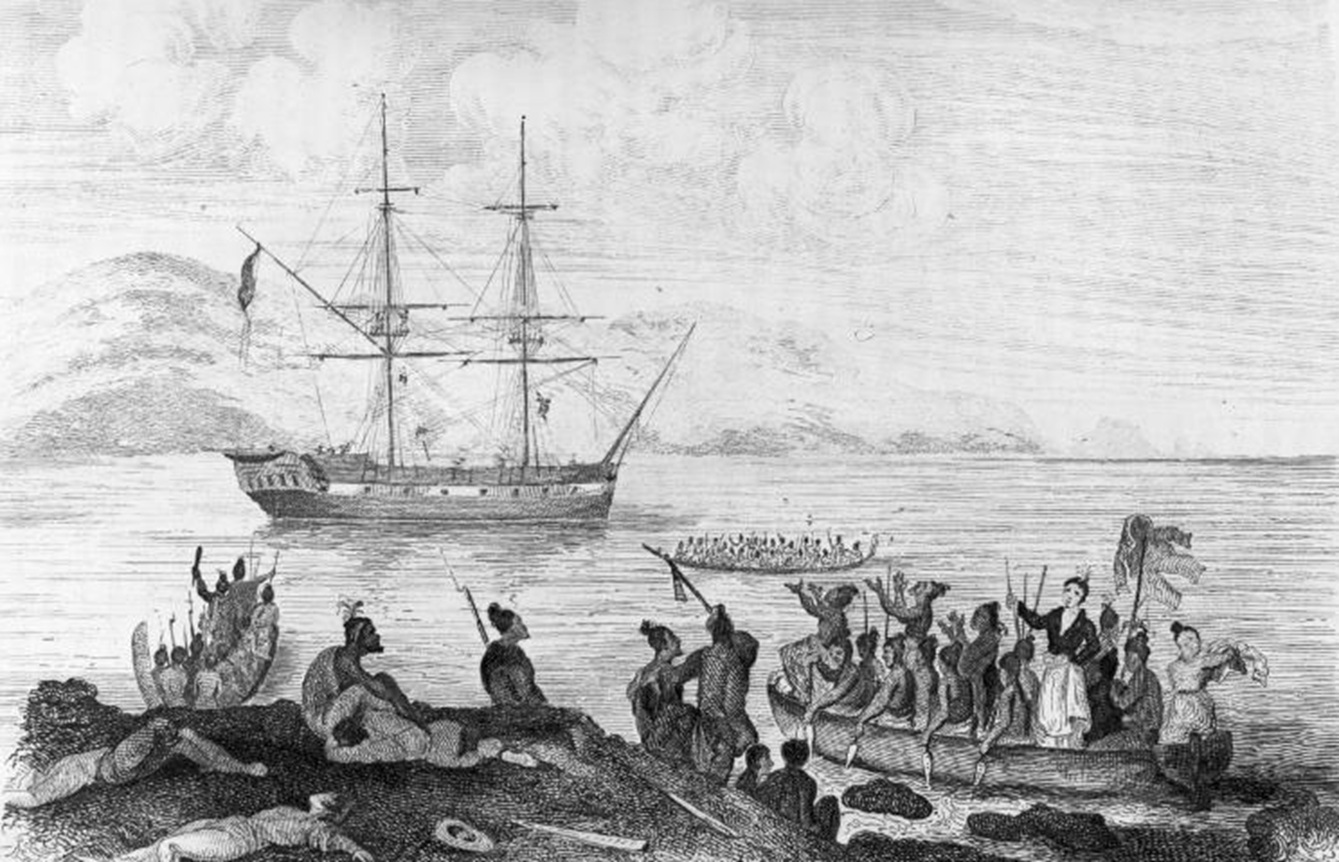

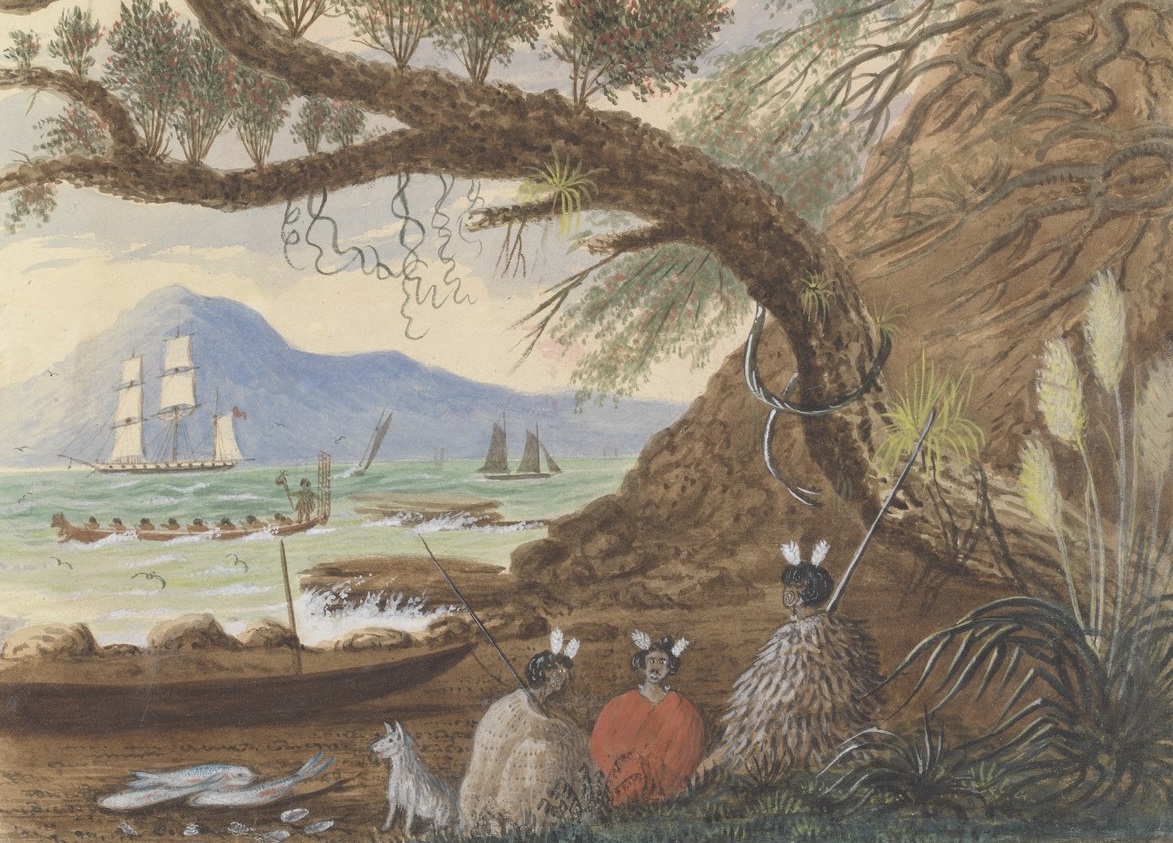

Abel Tasman Arrives In New Zealand

While Captain James Cook gets plenty of plaudits for mapping New Zealand and other lands in the region, the first Māori contact with Europeans came in 1642, when Dutch explorers, at the behest of the Dutch East India Company "discovered" New Zealand and named it after the Dutch province of Zeeland.

State Library of New South Wales, Wikimedia Commons

State Library of New South Wales, Wikimedia Commons

Meeting The Māori For The First Time

As Abel Tasman's sailors ventured towards the North Island, a group of Maori rowed out in their canoes to meet them. Feeling threatened by the strangers, the Māori attacked a group of Tasman's sailors, causing a brief skirmish between Tasman's vessel and the canoe of Māori. Tasman eventually departed the area, vowing to return.

Isaack Gilsemans, Wikimedia Commons

Isaack Gilsemans, Wikimedia Commons

Contact With The Päkehä

The Māori word for European New Zealanders is "Päkehä". The word likely originated with an old Māori legend of a "mythical, human like being, with fair skin and hair who possessed canoes made of reeds which changed magically into sailing vessels". As when the Europeans sailed to New Zealand, with their backs turned away from them, the Māori only saw their fair skin, leading them to call them "Päkehä".

Isaac Gilsemans, Wikimedia Commons

Isaac Gilsemans, Wikimedia Commons

James Cook Comes To New Zealand

Following the largely unsuccessful voyages of Abel Tasman in 1642, British explorer James Cook sailed to New Zealand in 1769 and met with Māori tribes on the North Island. Over the course of three days after landing, Cook's men shot at least three Māori. After Cook left the area, a French privateer, Marion Du Fresne, would land in New Zealand, leading to further confrontations with the Māori.

Nathaniel Dance-Holland, Wikimedia Commons

Nathaniel Dance-Holland, Wikimedia Commons

Marion Du Fresne Is Attacked

In 1772, despite the first few months of Du Fresne's arrival being marked by good relations with the Māori, Marion Du Fresne and 26 of his men were killed by a Māori war party. This increasingly worsened relationships between the Māori and Europeans who, by the late 18th-century, had begun to settle in the area.

National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons

The Boyd Massacre Of 1809

Since the passing of Marion Du Fresne, many skirmishes between the Europeans and Māori had broken out. Yet none were worse than the Boyd Massacre of 1809, when a group of Māori took the lives of between 66 and 70 sailors from the British ship, Boyd. The Māori attack was a retaliation for the whipping of their chief.

Louis Auguste Sainson, Wikimedia Commons

Louis Auguste Sainson, Wikimedia Commons

The Adoption Of European Norms

Although the Māori oral tradition remains strong today, it wasn't long before the Māori adopted writing as their primary form of communication and began converting their oral stories into written form. Furthermore, the European introduction of the potato was an agricultural revolution for the Māori, as was the introduction of the musket.

Charles Heaphy, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Heaphy, Wikimedia Commons

The Musket Wars

Eventually, this led to intertribal conflict between different groups of Māori: one that wanted to keep their traditions alive and not assimilate at such a rapid pace with the Europeans, and others who were more welcoming of European traditions. These skirmishes between different Māori tribes were known as The Musket Wars.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

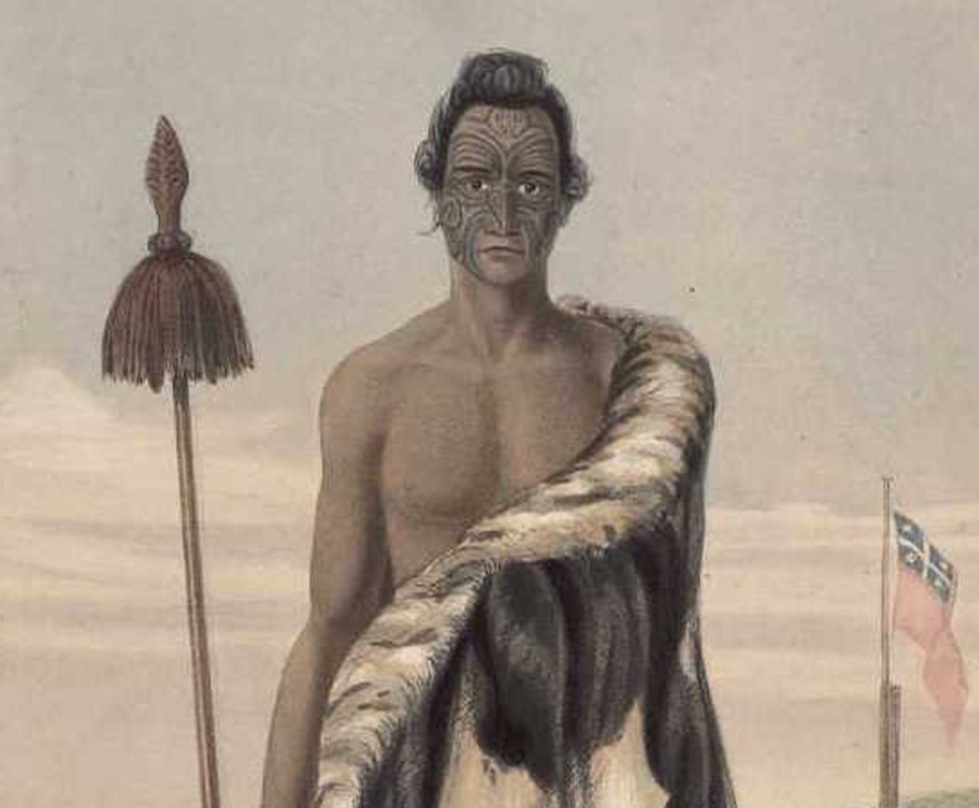

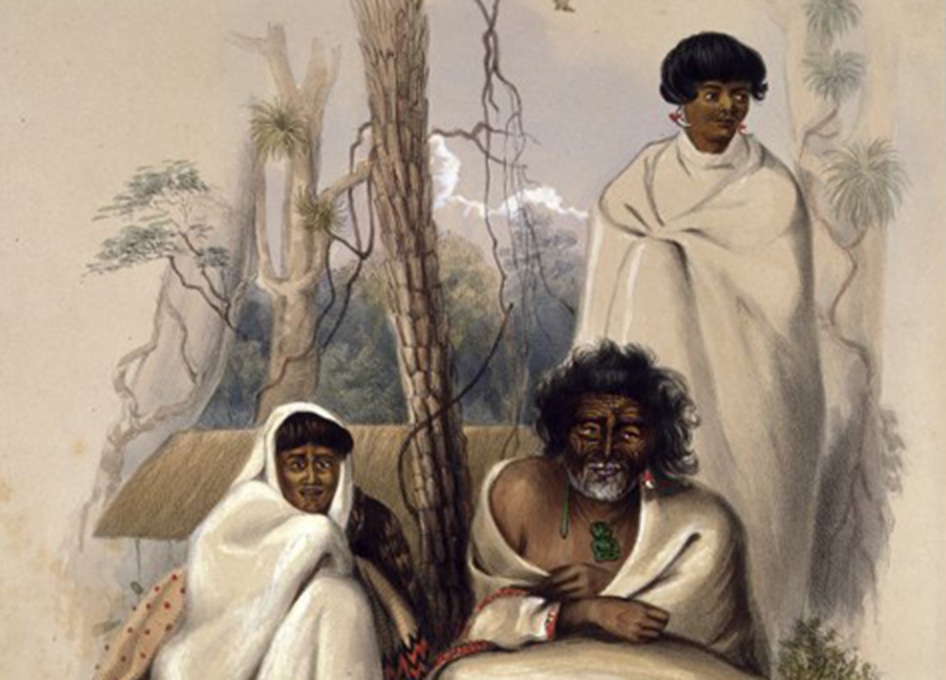

Warfare & Disease Bring High Mortality Rates

Unfortunately for the Māori, intertribal warfare and diseases like smallpox, influenza, and measles led to a decimation of the population. Estimates place the total percentage of lost Māori between 10 and 50% of the original Māori population.

George French Angas , Wikimedia Commons

George French Angas , Wikimedia Commons

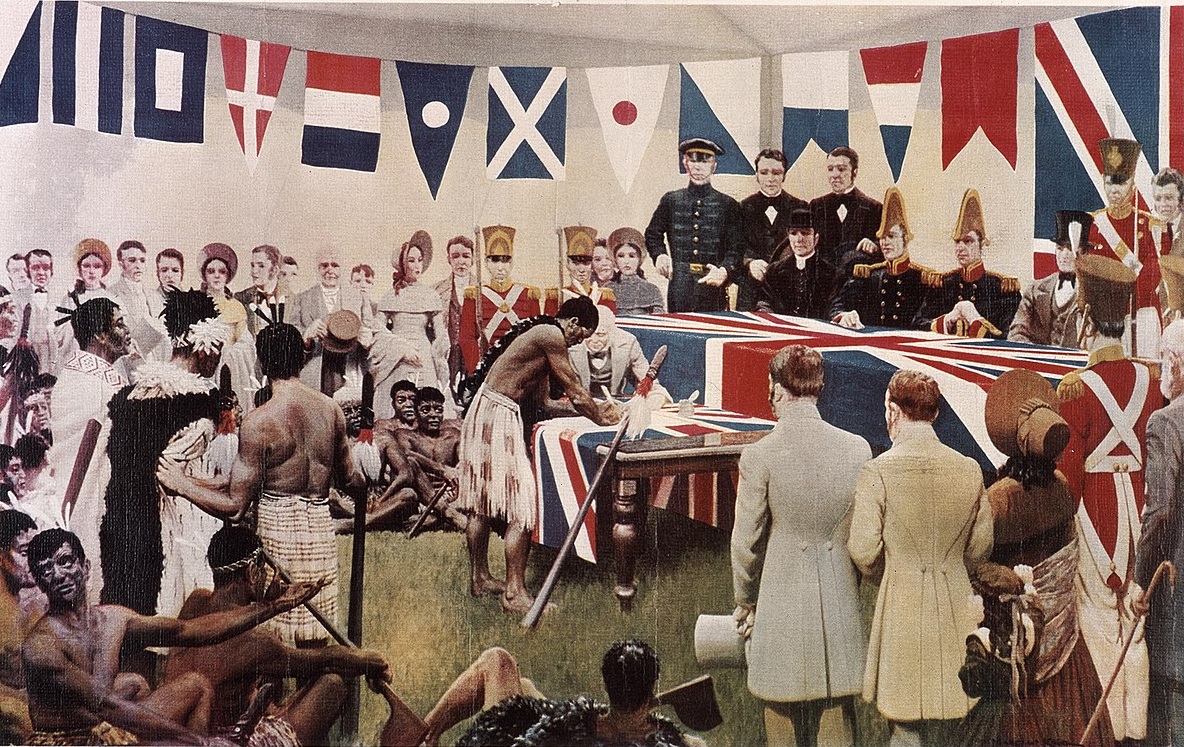

The Treaty Of Waitangi

The first semblance of Māori statehood and rights under British rule happened in 1839, when the British government sent Royal Navy Captain William Hobson to negotiate a treaty between the Māori and the British who had, by then, inhabited large parts of New Zealand. This was known as the Treaty of Waitangi.

Archives New Zealand from New Zealand, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Archives New Zealand from New Zealand, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Treaty Of Waitangi Gives Māori Rights

The negotiations between the Māori and Captain Hobson took several years, with Hobson having to make repeated trips to New Zealand. Eventually, by February 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was agreed upon, giving the Māori people rights as British subjects, and guaranteeing them property rights and tribal autonomy.

Archives New Zealand from New Zealand, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Archives New Zealand from New Zealand, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

British Complete Colonization Of New Zealand

In exchange for these rights and protection of Māori tribal autonomy, the British were granted the right to annex New Zealand as a British colony. Signed by the Crown and 500 Māori chiefs, the Treaty of Waitangi completed the British colonization of New Zealand.

Internet Archive Book Images,Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images,Wikimedia Commons

A See-Sawing Early Colonial Period

The early years of British colonization of New Zealand were marked by mainly positive relationships between the Crown and the Māori, with the latter setting up businesses, supplying food and other products for domestic and overseas trade. Despite this, several small conflicts soon sprang up throughout the country, leading to a much bigger conflict: the New Zealand Wars.

Archives New Zealand from New Zealand, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Archives New Zealand from New Zealand, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

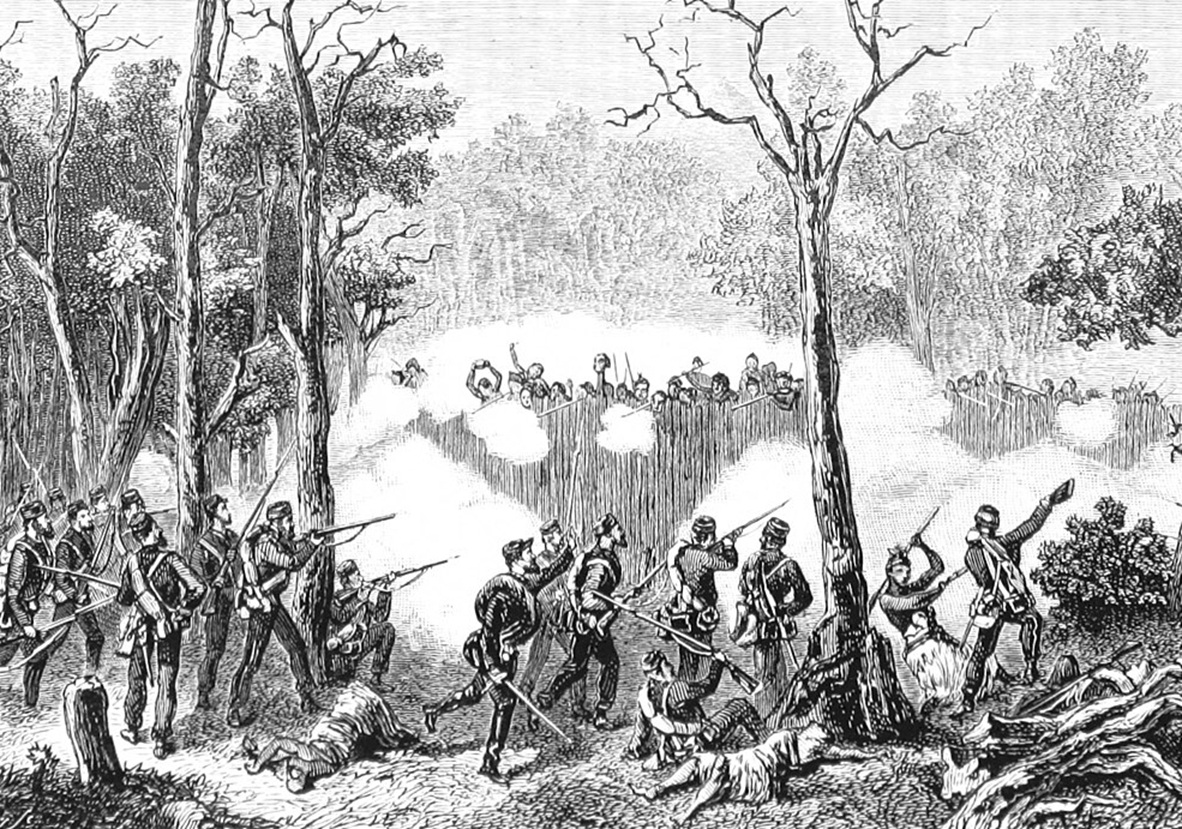

The New Zealand Wars

The New Zealand Wars divided the Māori. These were a series of skirmishes fought between 1845 and 1877, between British colonial forces and their Māori allies, and the rest of the Māori of New Zealand. The result was the confiscation of Māori land as punishment for what the colonial government deemed "rebellions".

A Court Case Decimates Māori Rights

The Treaty of Waitangi for 37 years, until 1877, when a wealthy Māori leader, Wi Perata, took the Bishop of Wellington to court over an alleged breach of the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. Unfortunately, the court ruled in the Bishop's favor. Even worse, it declared the treaty a simple nullity to domestic law, as it had been signed by "primitive barbarians".

Nathaniel Danceuploaded, Wikimedia Commons

Nathaniel Danceuploaded, Wikimedia Commons

The Dog Tax War

Further small conflicts followed that 1877 court case, culminating in the Dog Tax War of 1897. The precursor to the bloodless conflict was the imposition of a half-crown (roughly 50 cents) tax on every dog in the city of Hokianga. This was seen as an affront and many refused to pay, citing an infringement of treaty rights. Eventually, a series of armed protests sprang up. These were eventually de-escalated by a Māori representative without a shot being fired.

Charles Emilius Gold, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Emilius Gold, Wikimedia Commons

The Native Land Court Is Established

Following the Dog Tax War, a Māori Land Court was established in New Zealand (it still exists today) as a means of transferring Māori land from communal ownership to individual titles, paving the way for European settlers to offer to "buy" Māori land from the individual land owners, rather than needing to get the permission of the collective, as they had before.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

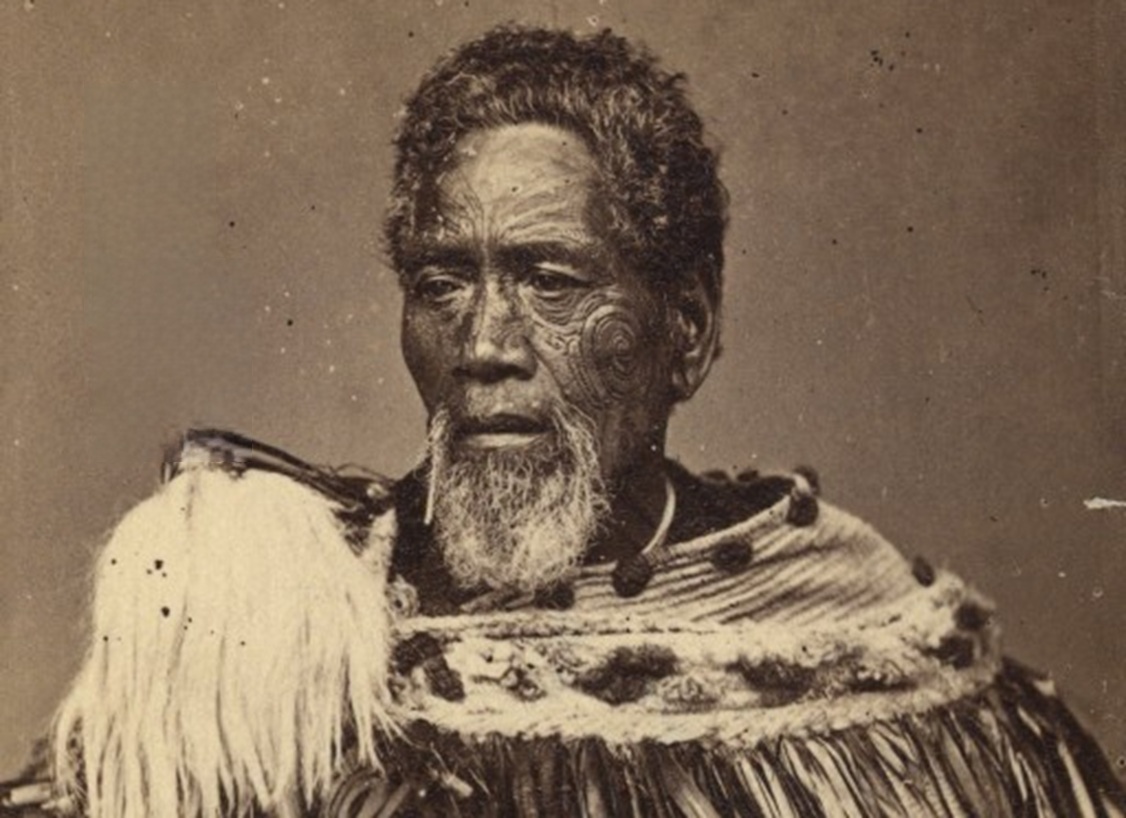

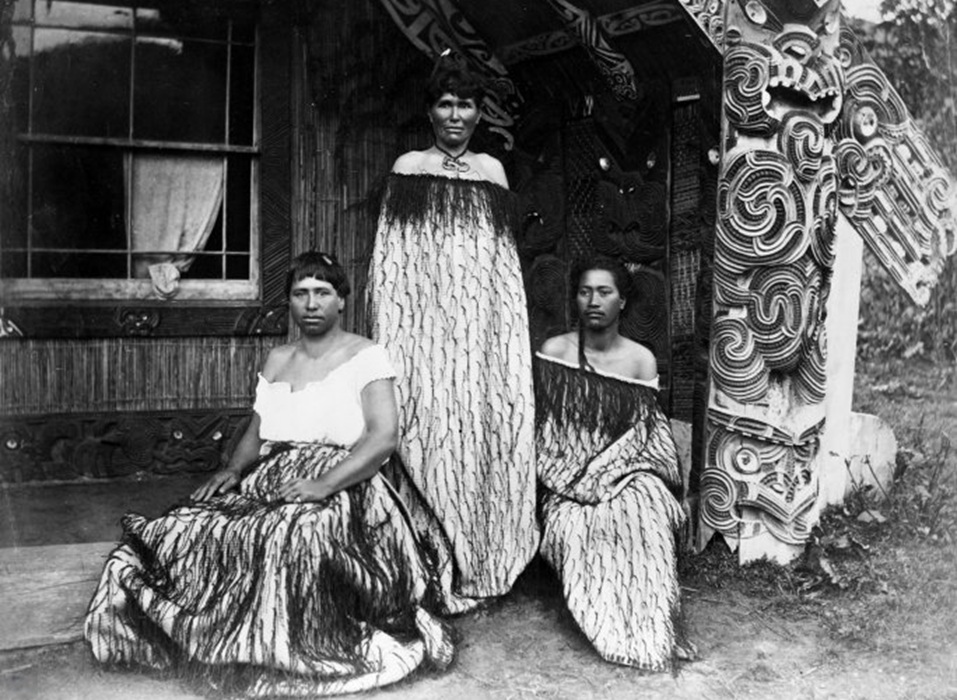

Decline Of The Māori In Early 20th Century New Zealand

As the early 19th century loomed, the Māori population in New Zealand was steadily declining and various colonial laws and policies expedited the decline of the Māori population by essentially forcing them to conform to the norms of the colonial government.

Elizabeth Pulman, Wikimedia Commons

Elizabeth Pulman, Wikimedia Commons

A Drive Toward Assimilation

In a census conducted in 1896, it was discovered that the Māori numbered 42,113, meanwhile the European settler population of New Zealand had ballooned to over 700,000. Seeing this as an increasing problem, Māori in various parts of New Zealand moved toward establishing their own government.

Keedwell, Ruby, Wikimedia Commons

Keedwell, Ruby, Wikimedia Commons

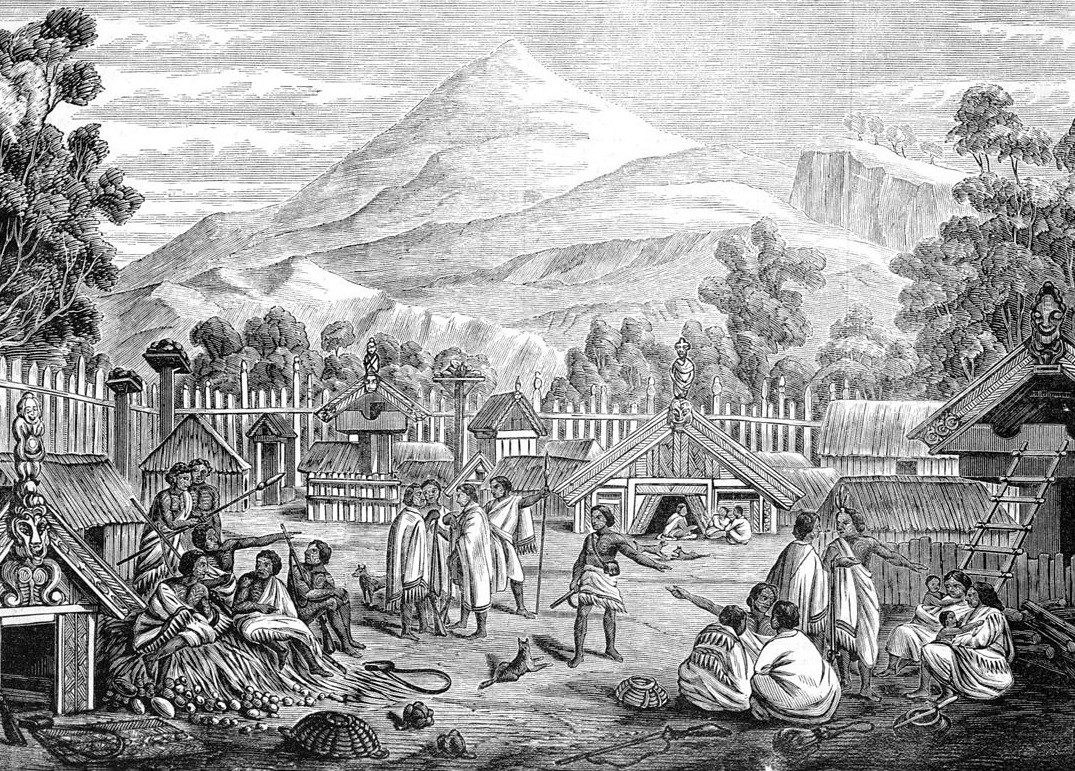

The King Movement

A harkening back to the days of old, before European contact and the decimation of the Māori population, the King Movement saw a group of Māori on the North Island begin setting up their own microstate. This included a police organization, a council of state, and a judicial system. They elected Te Wherowhero to rule as King.

George French, Wikimedia Commons

George French, Wikimedia Commons

The Reign Of Potatau I On North Island

The Māori of the North Island were finally free from the yoke of colonial oppression, having essentially set up their own state. The inaugural Māori king, Potatau I ruled from 1858 until 1860, ruling over a Māori monarchy of sorts, designed to directly combat the British crown and reassert ownership over Indigenous land.

![]() Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam, Wikimedia Commons

Special Collections of the University of Amsterdam, Wikimedia Commons

Māori Infighting & The First Taranaki War

Many Māori liked the British and were friendly with the colonial government, selling them lands and products, as mentioned above. However, many (like Potatau I) were not. In 1860, new immigrants coming to New Zealand from Britain began to flow into the North Island, leading many Māori to want to sell. One Māori, Te Teira of Taranaki, sold his land to immigrants without the consent of his tribe, precipitating an internal conflict known as the First Taranaki War.

Godber, Albert Percy, Wikimedia Commons

Godber, Albert Percy, Wikimedia Commons

The Fire In The Fern Engulfs The North Island

Although named after a fire, "The Fire In The Fern" is what the British called the final war between the colonial government and the Māori forces. Hostilities engulfed the entire North Island from 1864 to 1872, eventually being settled with yet another treaty.

Ebenezer and David Syme, Wikimedia Commons

Ebenezer and David Syme, Wikimedia Commons

The Tohunga Suppression Act Of 1907

In 1907, the colonial government passed the Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907. This was aimed at prohibiting Māori healers from practicing their methods, suppressing the Māori language in schools and generally erasing the Māori culture from existence. The act was sometimes enforced with capital punishment.

National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons

The Māori Take Sides In World War I

Despite various attempts by the colonial government to reduce the Māori population to near zero, it rebounded in the lead up to World War I, which saw the creation of the Māori Pioneer Battalion, for which 2,227 Māori signed up to join. By the end of the war, 336 Māori had been killed in action.

Archives New Zealand from New Zealand, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Archives New Zealand from New Zealand, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Devastating 1918 Influenza Pandemic

The 1918 influenza pandemic devastated much of the world, killing an incredible 60 million people. The Māori suffered greatly during this: a lack of access to primary healthcare and their treatment as second-class citizens (essentially) by the government of New Zealand resulted in a death rate that was 7.3 times higher than that of European New Zealanders.

J.A. Gilfillan, E. Walker, Day & Son, Wikimedia Commons

J.A. Gilfillan, E. Walker, Day & Son, Wikimedia Commons

The Māori Contribution To WWII

As in WWI, the Māori answered New Zealand's call at the onset of the Second World War, making up the 28th Māori Battalion, which saw action in Greece, Italy, and North Africa. By the end of the war, over 16,000 Māori had given their lives for their country. One Māori soldier, Te Moananui-a-Kiwa Ngārimu, won a Victoria Cross for his bravery on the battlefield.

Davies L B (Lt), Wikimedia Commons

Davies L B (Lt), Wikimedia Commons

The Cultural Revival Of The Māori

In the post-World War II era, the Māori have experienced a cultural revival, with Māori being recognized as the the second official language of New Zealand in 1987. Additionally, the New Zealand government and the Māori people began formal proceedings to return stolen Māori land to its rightful owners.

Broddi Sigurðarson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Broddi Sigurðarson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Current State Of The Māori In New Zealand

As land returns continue, the Māori have also been granted 29 seats in New Zealand's 120-seat Parliament, and many Māori-language schools, known as "kōhanga reo", have popped up. Now, there are 29 Māori MPs, two Māori TV channels, and 21 Māori radio stations. Although New Zealand and the Māori have a long way to go to heal relations, meaningful land reclamations are an important first step.

You May Also Like:

The Creepiest Abandoned Attractions

Sources: