The Pitcairn Islands

The Pitcairn Islands are a group of volcanic islands in the middle of the South Pacific, nearly equidistant from both New Zealand and Chile—and they’ve got a past so dark that it seems to have foreshadowed the current controversies the islands face.

What Are The Pitcairn Islands?

The group is made up of four islands: Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie, and Oeno Islands. They are the only British Overseas Territory in the Pacific Ocean. Though it became a British colony in 1838, there were people on the islands long before that…

The First Residents

There’s evidence that the first settlers on the Pitcairn Islands were Polynesians who lived on Pitcairn and Henderson Islands in the 11th century. They may have traded items with people on Mangareva Island nearby, including basalt and obsidian for coral and pearl shells.

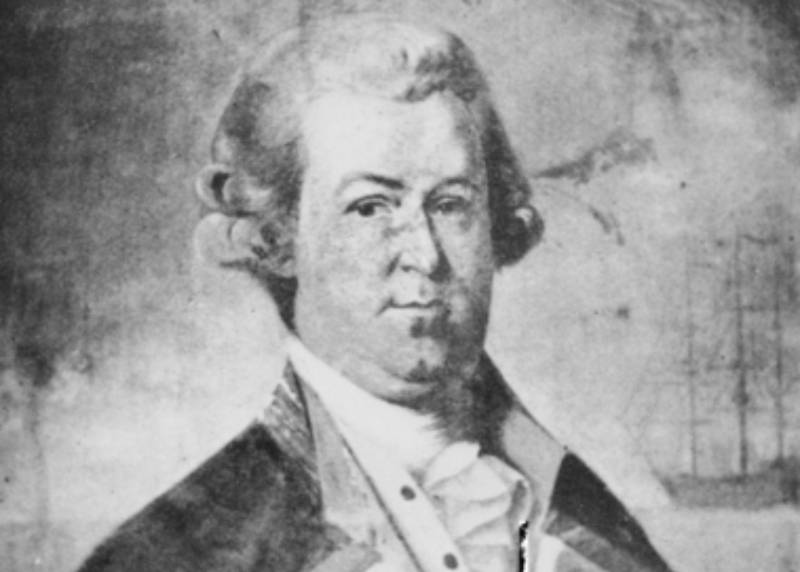

Sir John Barrow, Wikimedia Commons

Sir John Barrow, Wikimedia Commons

A Self-Contained Paradise

However, the Pitcairn Islands mostly had a self-contained economy at this time. They used the basalt to make adzes, which are tools used in agriculture and woodworking. These were exemplary examples of the tools. The Pitcairns seemed quite idyllic—and then something went horribly wrong.

The Vanishing

Life thrived on the Pitcairn Islands for four centuries—and then suddenly, it disappeared. It likely had something to do with their relationship with Mangareva Island, which lost its population and culture after deforestation. After that, it was a ticking doomsday clock…

State Library of New South Wales, Wikimedia Commons

State Library of New South Wales, Wikimedia Commons

A Decimated Society

There were also civil conflicts in that area at the time which affected trade routes and vanquished natural resources. Without the support of Mangareva Island, the population on the Pitcairns dwindled and eventually went extinct…or so it seemed.

Escape To Easter Island

It’s possible that the remaining inhabitants on the Pitcairn migrated to Easter Island, as there are similarities in language and tool styles between the two cultures. Though the islands are some 1,900 kilometers apart, modern historians tried to recreate the journey and were able to do it in just 17 and a half days.

Ian Sewell, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ian Sewell, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Deserted Island

In January of 1606, a Portuguese explorer rediscovered the Pitcairn Islands, which by that time were totally uninhabited. Then, in 1767, a British team led by Captain Philip Carteret came across the empty island and marked down its coordinates.

Jersey Museum and Art Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

Jersey Museum and Art Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

Who Were The Pitcairn Islands Named For?

Captain Carteret decided to name the first island Pitcairn after teenaged crew member Robert Pitcairn, who was the first to spot it from their ship. Though he gave it his name, Robert never stepped foot on the island, as its high cliffs prevented the crew from stopping there—and he ultimately ended up on the ill-fated ship Aurora, which was lost at sea three years later.

Makemake, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Makemake, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Bounty Comes To Pitcairn

The Pitcairn Islands had been uninhabited for nearly two centuries, but not long after Captain Carteret and his crew rediscovered them, another group of people came along—and this time, they decided to stay.

Dan Kasberger, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dan Kasberger, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mutiny On The Bounty

It might be the most infamous mutiny in history, and it’s one of the reasons why we know about the Pitcairn Islands today. After Fletcher Christian led a group of crewmen against the Bounty’s captain in 1789, many of the crew headed either to Tahiti or the Pitcairn Islands—and they were forever changed as a result.

Robert Dodd, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Dodd, Wikimedia Commons

All Aboard

Fletcher Christian first went to Tahiti aboard the Bounty and picked up some passengers along the way. He’d heard about the Pitcairn Islands via Captain Carteret’s reports. Fletcher gathered eight Englishmen, one Scot, six Polynesian men, and 12 Tahitian women on the Bounty and set sail for the Pitcairn Islands.

Trailer screenshot, Wikimedia Commons

Trailer screenshot, Wikimedia Commons

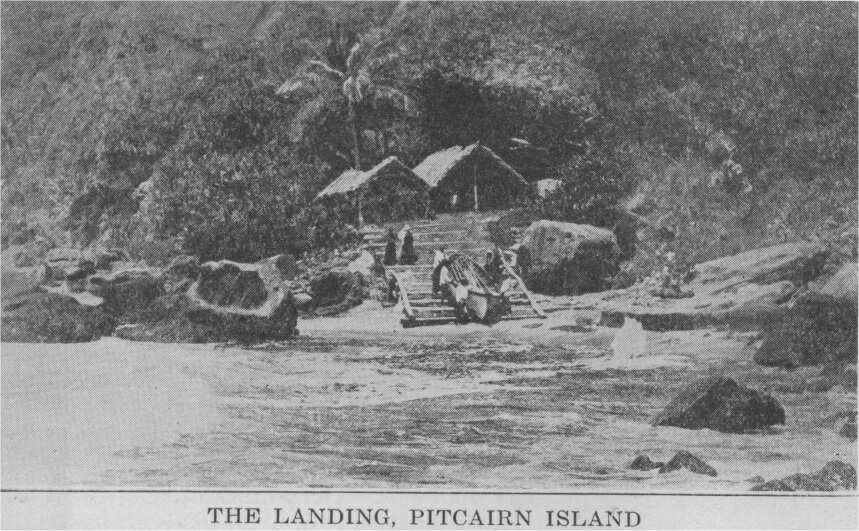

A Safe Haven

Christian knew that he faced prosecution if the Captain he’d betrayed were ever to track him down, and the Pitcairn Islands proved to be a perfect safe haven. They disassembled the ship to use the materials on the island and burned what remains before heading inland, where they couldn’t be spotted by passing ships, thanks to the high cliff walls.

Makemake, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Makemake, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A New Life

The Pitcairn Islands had everything that a bunch of castaways could need—food, water, and fertile land. There were also leftover carvings from the islands’ first society, including worship sites, tiki carvings, and tools. Soon enough, Christian had a child with one of the Tahitian women.

But this idyll didn’t last…

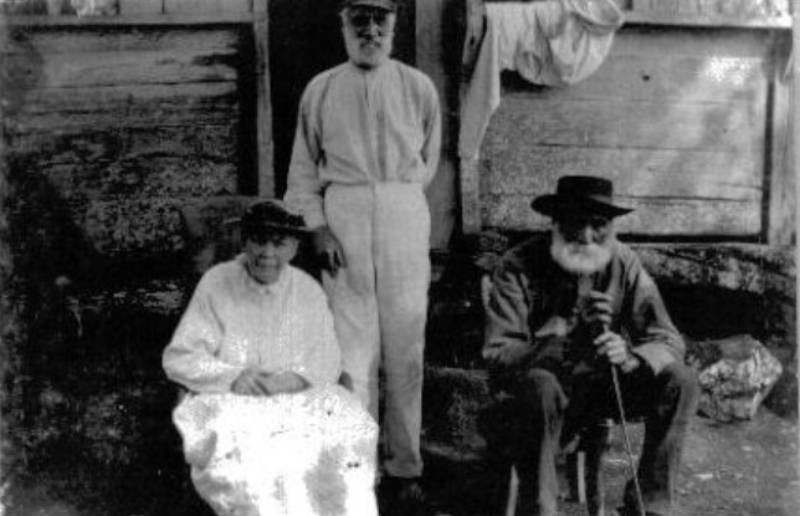

Pitcairn Islanders, Wikimedia Commons

Pitcairn Islanders, Wikimedia Commons

An Island Divided

Though the Europeans and the Polynesians co-existed peacefully at first, eventually, tensions mounted between the two groups over the way the Europeans treated others. Originally, both groups had worked together to keep things going, but over time, the mutineers stopped contributing. On top of that, they had other problems.

Seventh-day Adventist Church, Wikimedia Commons

Seventh-day Adventist Church, Wikimedia Commons

Happy Hour

One of the mutineers had figured out how to distill brandy and built a still, which the Europeans took advantage of—to the detriment of their daily tasks. This, along with romantic rivalries, also resulted in terrifying outbursts between the two groups. Eventually, a line was drawn—and it was too late to go back.

A Mutiny Against The Mutineers

Eventually, four Polynesian men made a plan to get rid of the mutineers. On September 20, 1793, they set their plan in motion. By the end of it, five Europeans and four Polynesians had lost their lives—a significant part of the Pitcairn Islands’ small population.

Admiral Edward Gennys Fanshawe, Wikimedia Commons

Admiral Edward Gennys Fanshawe, Wikimedia Commons

The Aftermath

Though two of the remaining Europeans managed to create a détente, the consequences of what had happened on September 20 reverberated throughout the colony. Paranoia reigned. One man took his own life. The brandy flowed. But as the years passed and the population of the first set of settlers dwindled, the people of the Pitcairn Islands had a second chance.

Michael John Nicoll, Wikimedia Commons

Michael John Nicoll, Wikimedia Commons

The Next Generation

One of the mutineers, John Adams, took the Bible from the Bounty and began to teach the children and women. Some 15 years after the second “mutiny,” contact was reestablished with Britain after two of their ships happened by the islands. There was a chance that they might take action for the mutiny on the Bounty—but once they saw how well the society was functioning, they decided to let it be.

J.A. Moerenhout, Wikimedia Commons

J.A. Moerenhout, Wikimedia Commons

From Anarchy To Order

After this tumultuous period, the society on Pitcairn became a model of order and moderation. Eventually, the last surviving mutineer, Adams, passed on. In his absence, a visiting British-Chilean sailor took over, along with help from one of the first children born on the island.

Makemake, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Makemake, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

You Can’t Go Home

In 1831, a number of the Pitcairn Islanders who were originally from Tahiti asked the British government to return to their home, as they were worried about overcrowding. Unfortunately, they didn’t like what they found: "immorality, saloons, vile dances, gambling, and scarlet women."

Admiral Edward Gennys Fanshawe, Wikimedia Commons

Admiral Edward Gennys Fanshawe, Wikimedia Commons

Leadership Problems

Within six months, the Tahitians who’d survived their brief sojourn back home asked to go back to Pitcairn—but the troubles didn’t stop. An American pretending to be British had himself elected leader, only to enact a totalitarian regime. Eventually, the Pitcairnese kicked him off the island—and looked back to the British for guidance.

Mutiny To Capitulation

Ironically, the people of Pitcairn Island, which had begun as a mutineers’ colony, ended up becoming a British colony—the first in the Pacific—in 1838. Even more remarkably, they were the second country in the world to give women the right to vote. But as the population grew, so did the problems.

Seventh-day Adventist Church, Wikimedia Commons

Seventh-day Adventist Church, Wikimedia Commons

Pitcairn To Norfolk

Queen Victoria offered the people of Pitcairn Island the chance to move to a bigger island, Norfolk Island, a former penal colony. Though all 163 left, roughly one-third returned within two years—and the consequences were disastrous.

Steve Daggar, CC BY 3.0 , Wikimedia Commons

Steve Daggar, CC BY 3.0 , Wikimedia Commons

Back Again

In the time that the Pitcairnese were gone, a group of shipwreck survivors had briefly lived on the island and vandalized some homes and the grave of John Adams. Additionally, France had nearly attempted to annex the island, not realizing it was a British territory.

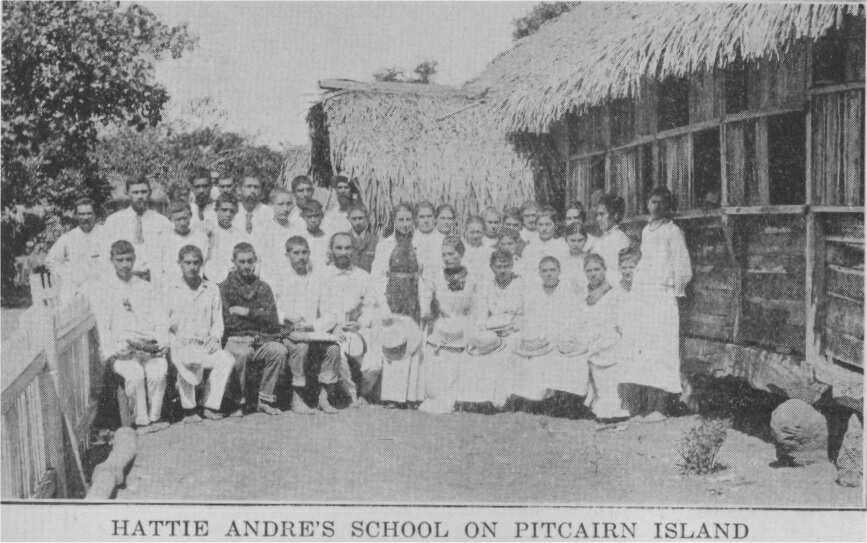

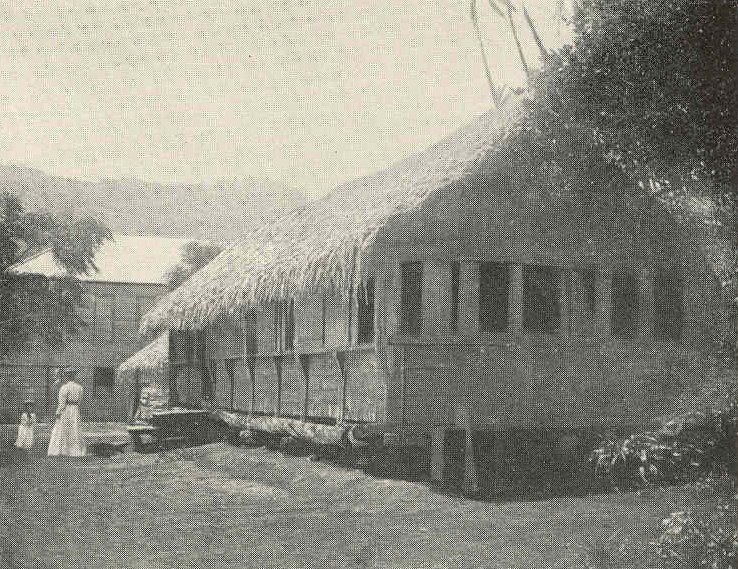

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

From Singular To Plural

Pitcairn Island received support from Britain in the form of food, building materials, and other gifts. On top of that, Britain also annexed the three other islands nearby: Henderson, Oeno, and Ducie. In 1937, the population peaked at 233. But since then, things have gone downhill.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Feast & Fallow

In the years that followed, the population dwindled as people left for New Zealand and Australia. And as fewer deliveries from Britain made their way to the Islands, their residents began to sell off pre-European artifacts and Bounty memorabilia to collectors to support themselves.

Henning Axt, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Henning Axt, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Pitcairn Islands Now

The population of the Pitcairn Islands as of 2021 was 47 people, and the primary sources of income for the island are landing fees and tourism. Unfortunately, the Islands have also been tainted by scandal.

Paradise Lost

In 2004, the Pitcairn Islands were rocked when 13 current and former residents were charged with sex-related offenses—including the mayor and magistrate of the Islands. Six were convicted, and the British government had to actually establish a penal institution on the Islands so they could serve their sentences.

History repeated itself in 2010 when another mayor found himself in hot water for similar reasons.

Makemake, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Makemake, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Deep Legacy

Over 60% of Pitcairn Islanders are descendants of the Bounty mutineers and Polynesians, though the Islands do try to attract newcomers. If you have NZ$30,000 in savings and NZ$140,000 to build your own home, you can apply to live there. However, if that’s a bit much, Pitcairn Islanders welcome visitors via ship for a week or two, stay with a resident, and experience Pitcairn’s local culture.