The Last Uncontacted Tribe of Australia

The Pintupi Nine—once whispered about as Australia’s final uncontacted tribe—shocked the world the day they stepped out of the vast desert, lowered their spears, and revealed themselves after a lifetime in isolation.

Years later, the surviving members are finally breaking their silence. From their deep-rooted traditions to the moment their world was transformed—this is the extraordinary journey they’ve carried alone for far too long.

Who were they?

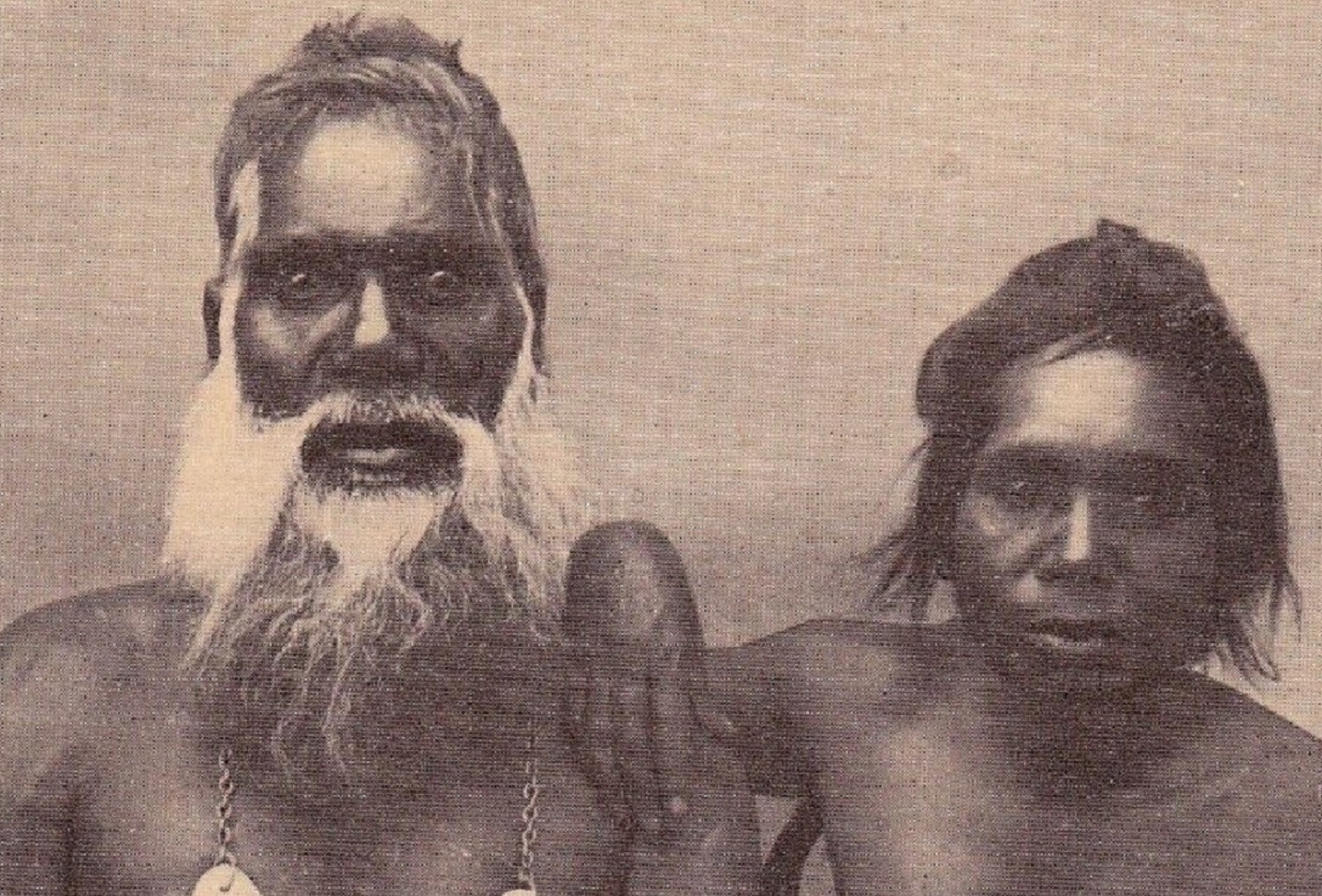

The Pintupi Nine were a group of nine Pintupi people who remained unaware of European colonization of Australia for many, many years.

They’ve become known as, “The Lost Tribe” of Australia.

How big was their tribe?

Much like their group name, The Pintupi Nine, the indigenous tribe consisted of only nine tribe members—which was one family unit.

What was their family unit like?

The nine family members consisted of two co-wives, Nanyanu and Papalanyanu, and their seven children: four brothers and three sisters.

The women shared a husband who had passed not long before they emerged from the desert.

Where did they live?

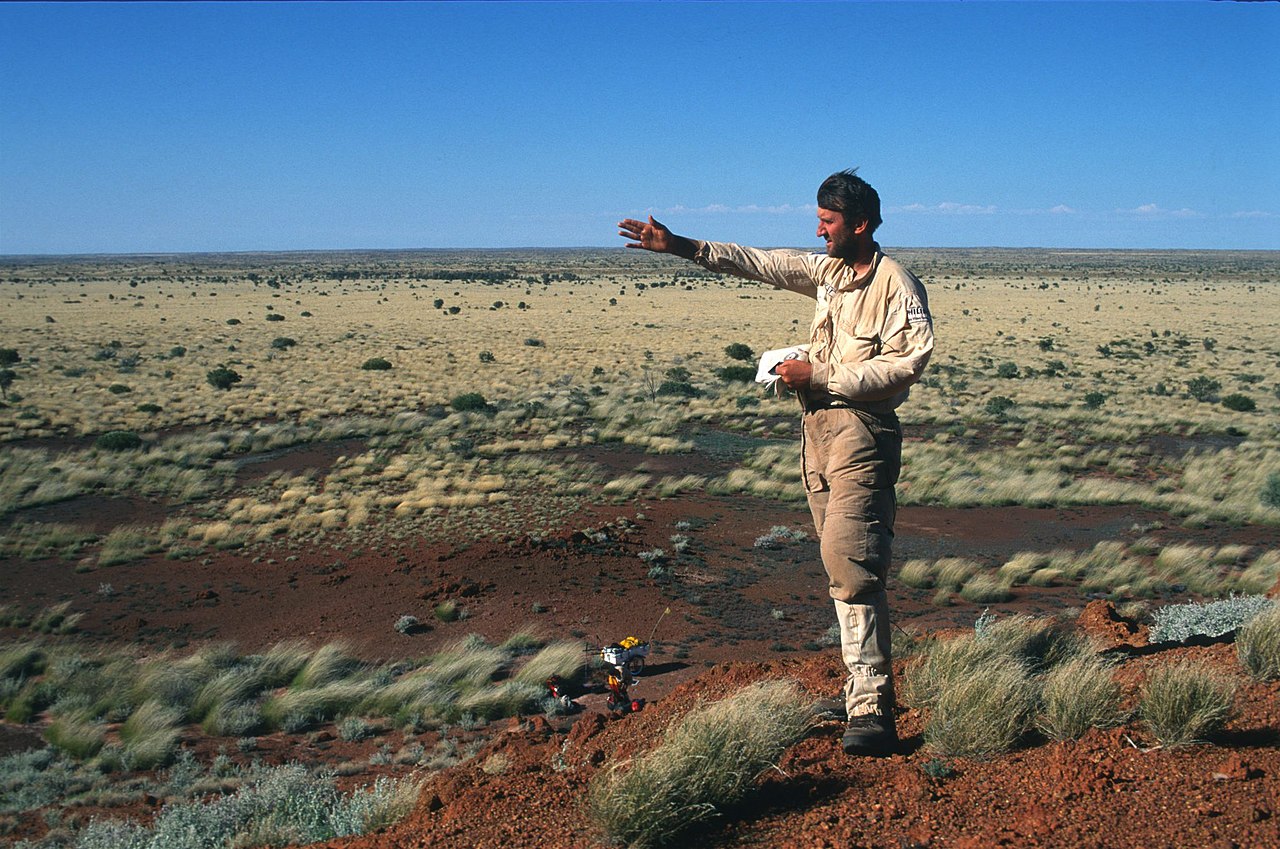

The Pintupi Nine lived a desert-dwelling nomadic lifestyle in Australia's hot Gibson Desert, where the majority of people living in the area were Indigenous Australians.

Fundacja Marka Kamińskiego, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Fundacja Marka Kamińskiego, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

How did they live?

Like many nomadic families before them, they drifted from waterhole to waterhole across the burning desert, “chasing the clouds,” as one survivor recalled—always moving where the rare, life-saving rain chose to fall.

They lived as true hunter-gatherers, carrying generations of knowledge in every step they took across the sand.

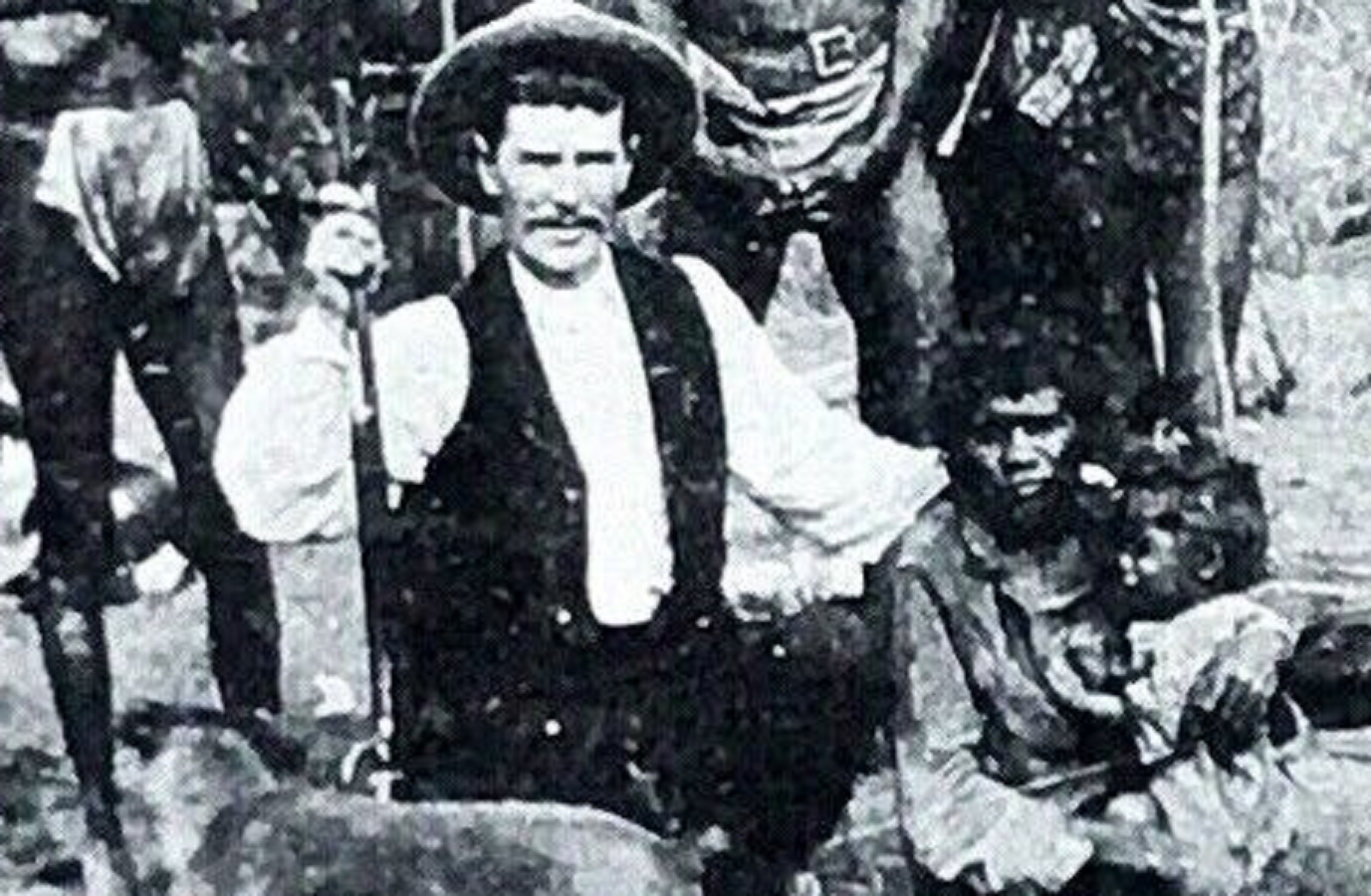

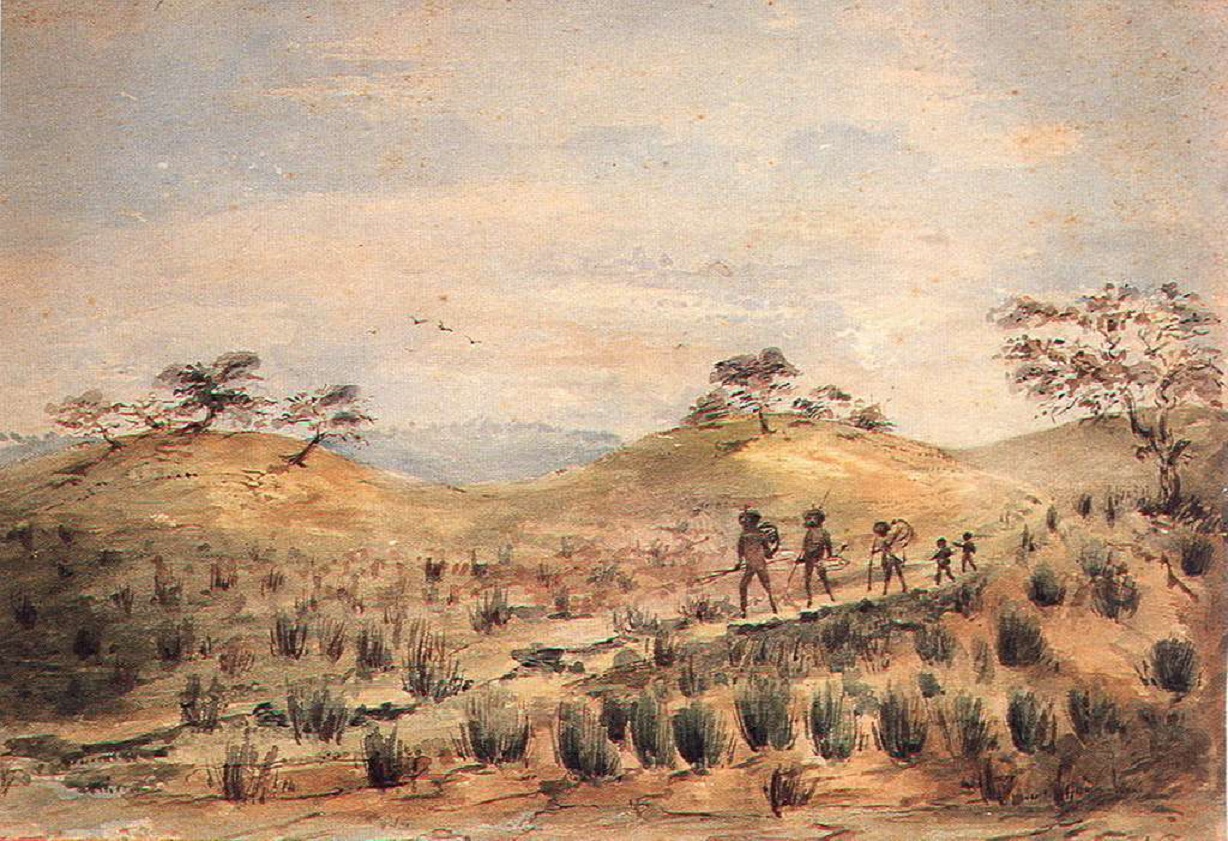

Kathryn Gergett and Susan Marsden Adelaide: A brief History (1996), Picryl

Kathryn Gergett and Susan Marsden Adelaide: A brief History (1996), Picryl

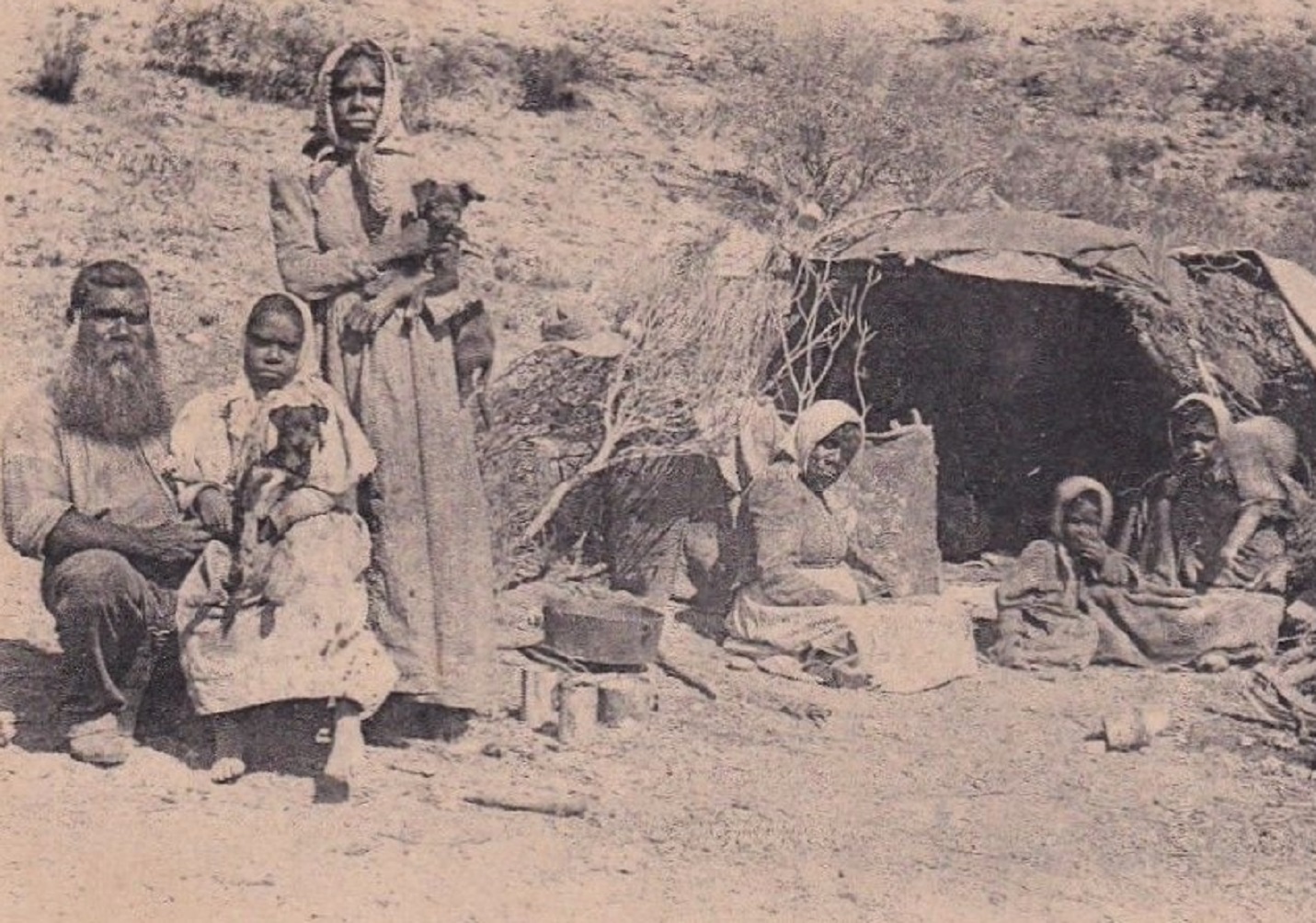

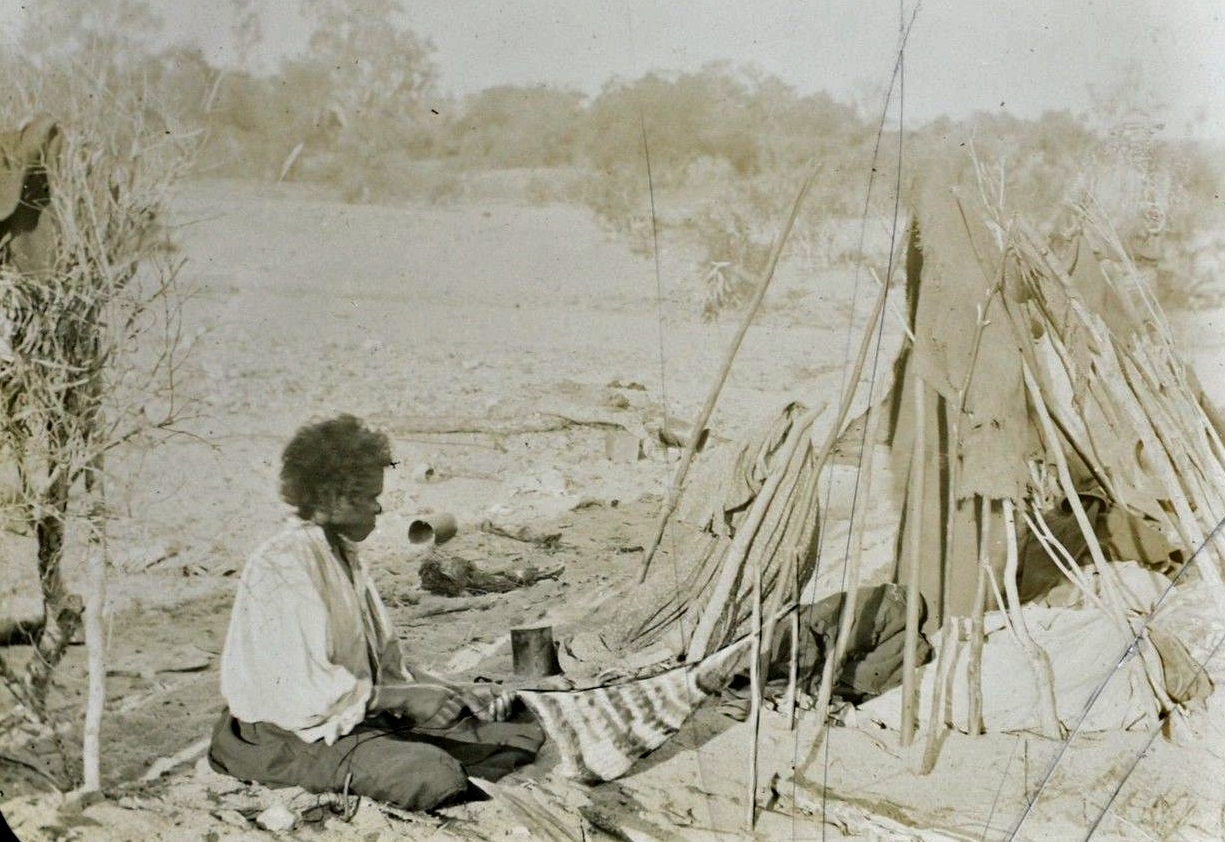

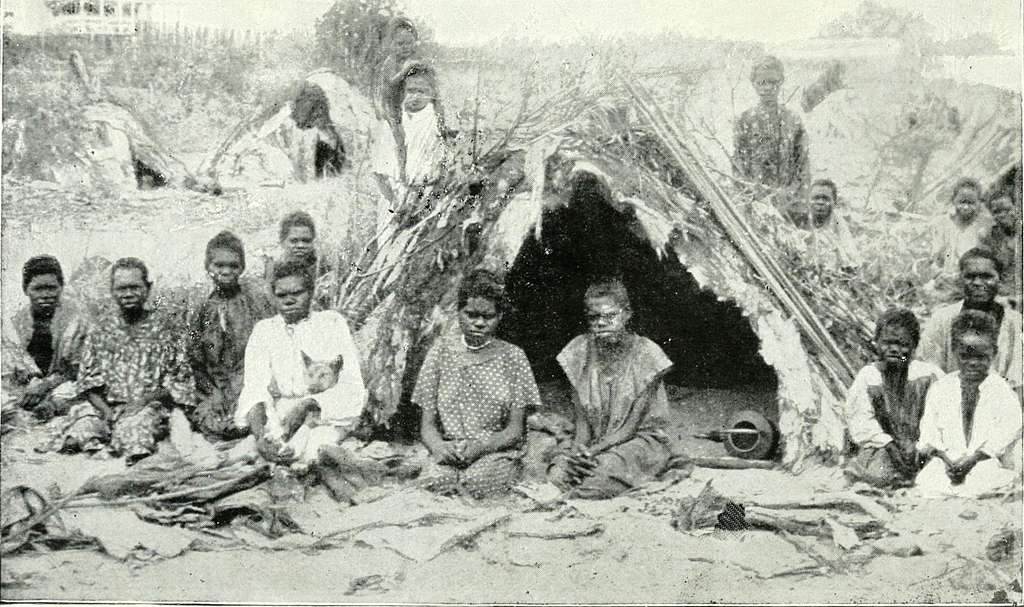

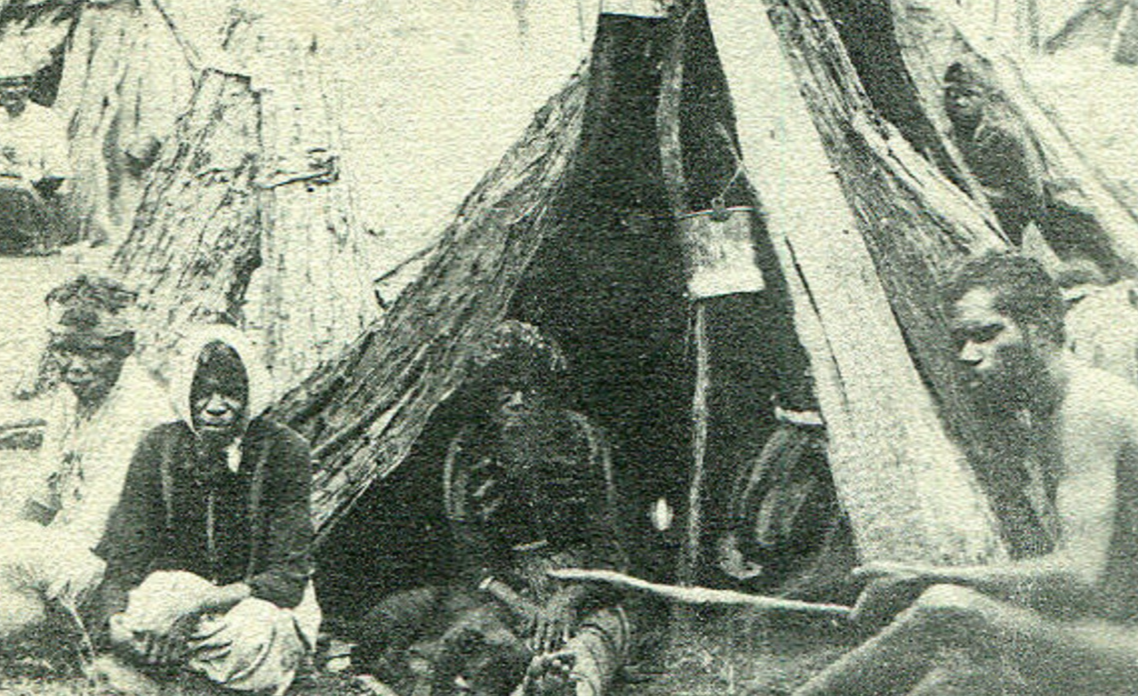

What were their homes like?

Since they moved around a lot, their encampments were built to be very temporary—sometimes they only stayed in one place overnight.

Was anything permanent?

Prior to severe droughts, larger camps were set up near permanent waterholes. But this has not been the case for many decades now.

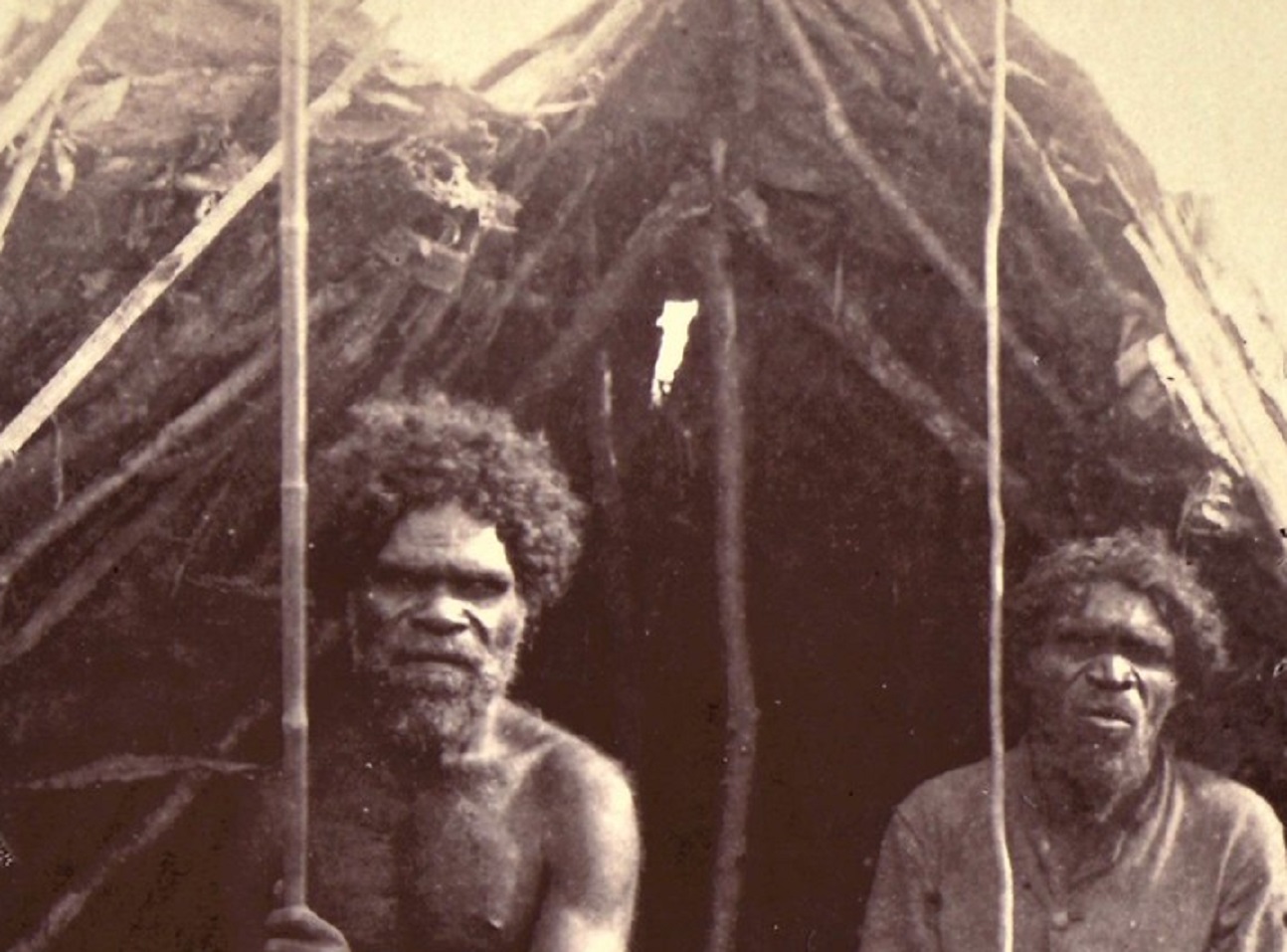

What were their shelters made from?

Traditional camp shelters were a simple windbreak made of brush found in the area.

Did they family sleep together?

Traditional Pintupi camps were segregated by gender and marital status: unmarried men and youths lived in one camp, with single women in another nearby; each husband-wife pair and their young children camped together.

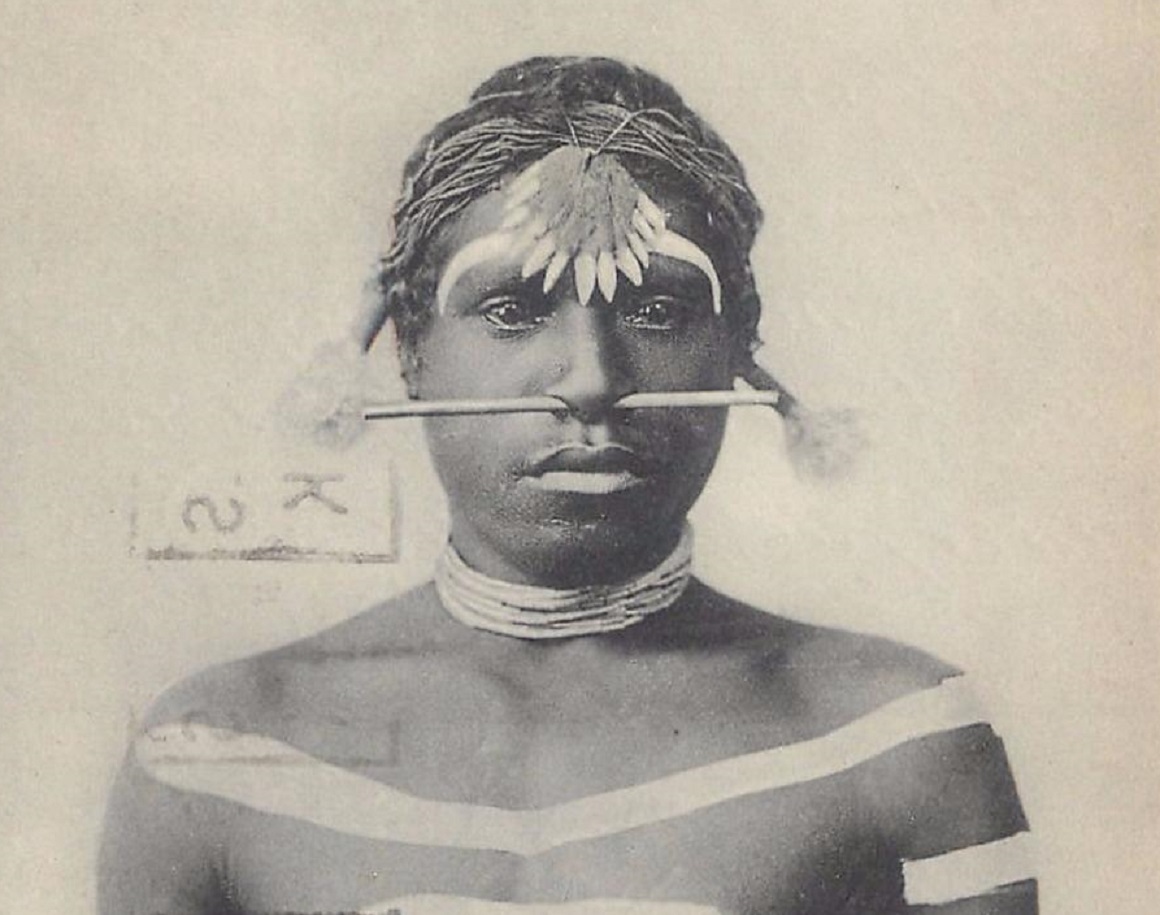

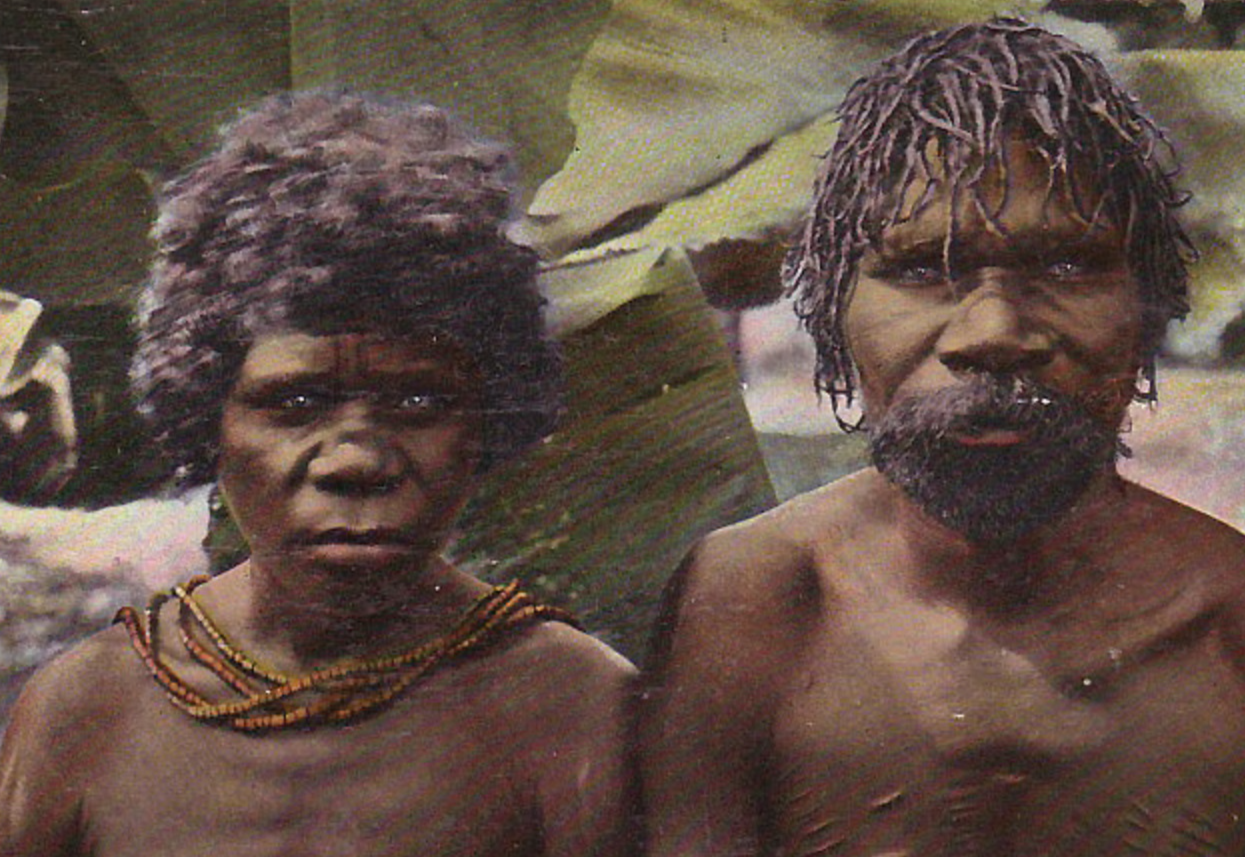

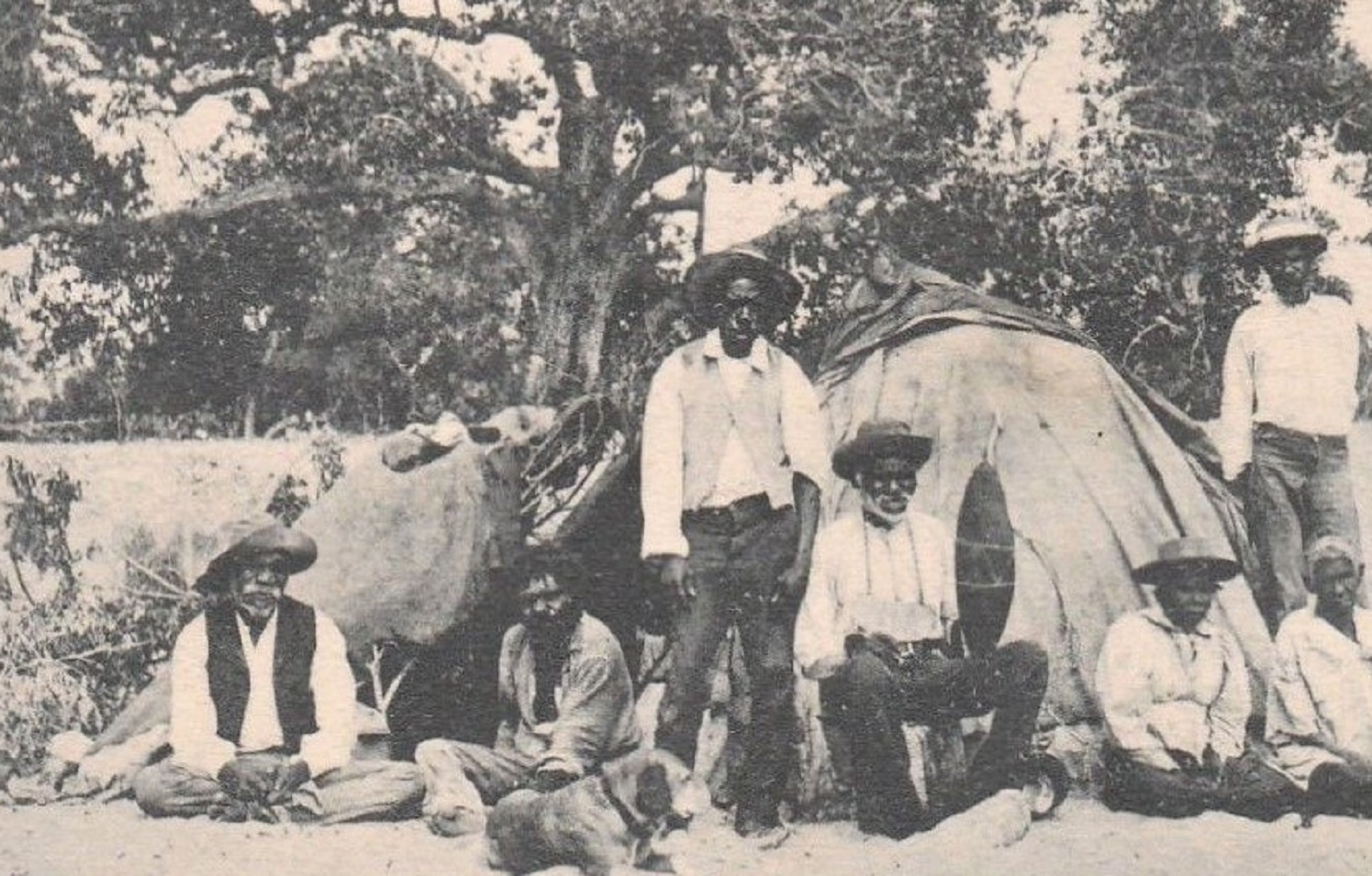

What did they wear?

Traditional Pintupi people lived with little need for clothing. Some wore woven hair-string belts, while others adorned themselves with striking body paintings and elaborate feathered headpieces that carried cultural meaning older than memory itself.

But once colonization swept across their lands, the old ways began to shift. Bit by bit, outside clothing replaced their ancestral adornments—marking the beginning of a transformation they never asked for.

What did they eat?

The Pintupi tribe’s diet consisted mostly of goannas (lizard), rabbits, small cats, and native plants found in their surroundings. Vegetation was limited though due to the dry climate.

Sometimes larger game was hunted, like kangaroos, wallabies, and emus when they were available.

How did they find water?

The Australian desert is very hot and dry, making water extremely limited. The tribe relied on rock and claypan caches in the hills and underground soakage, and wells in the gravel pan and sandy dunes.

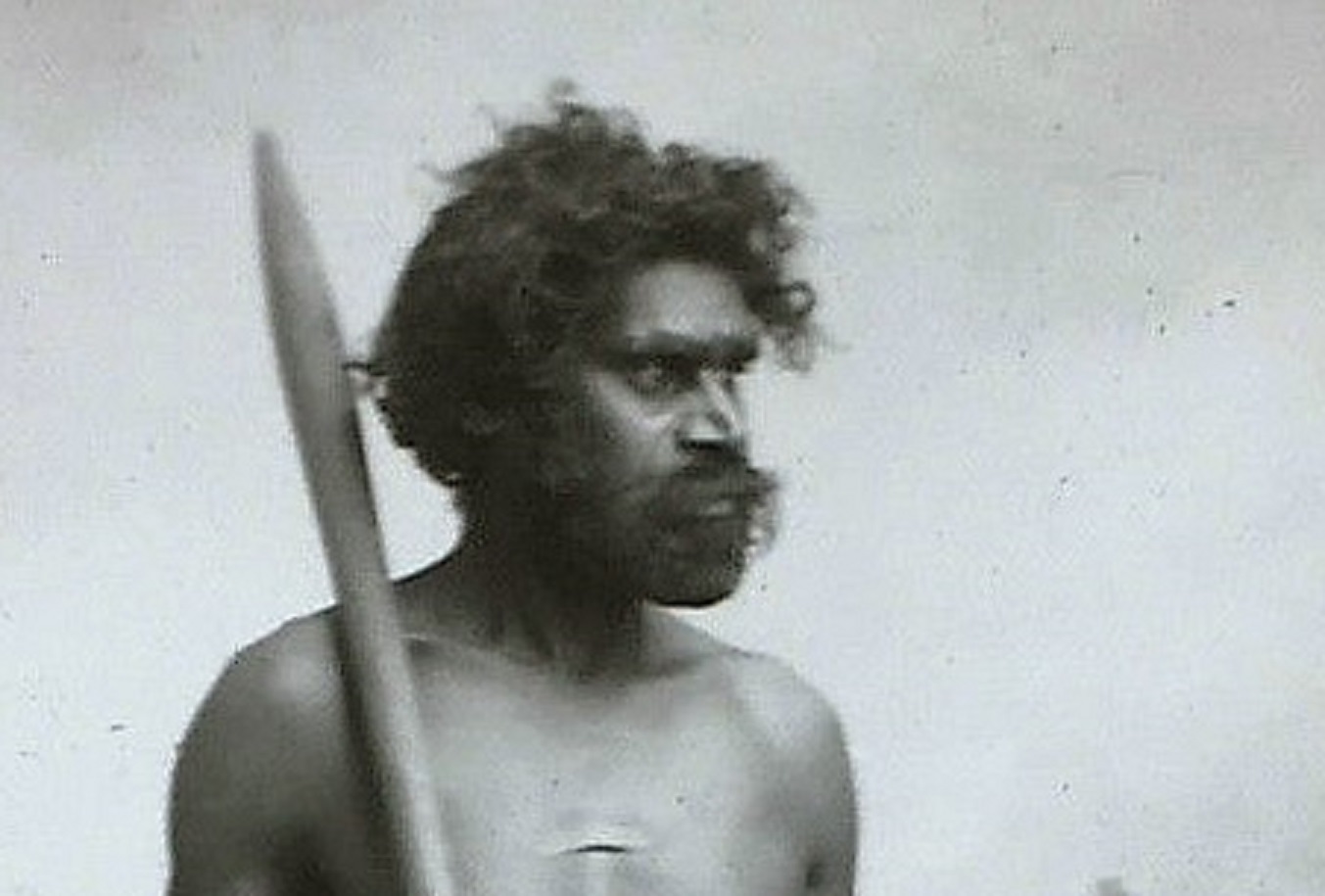

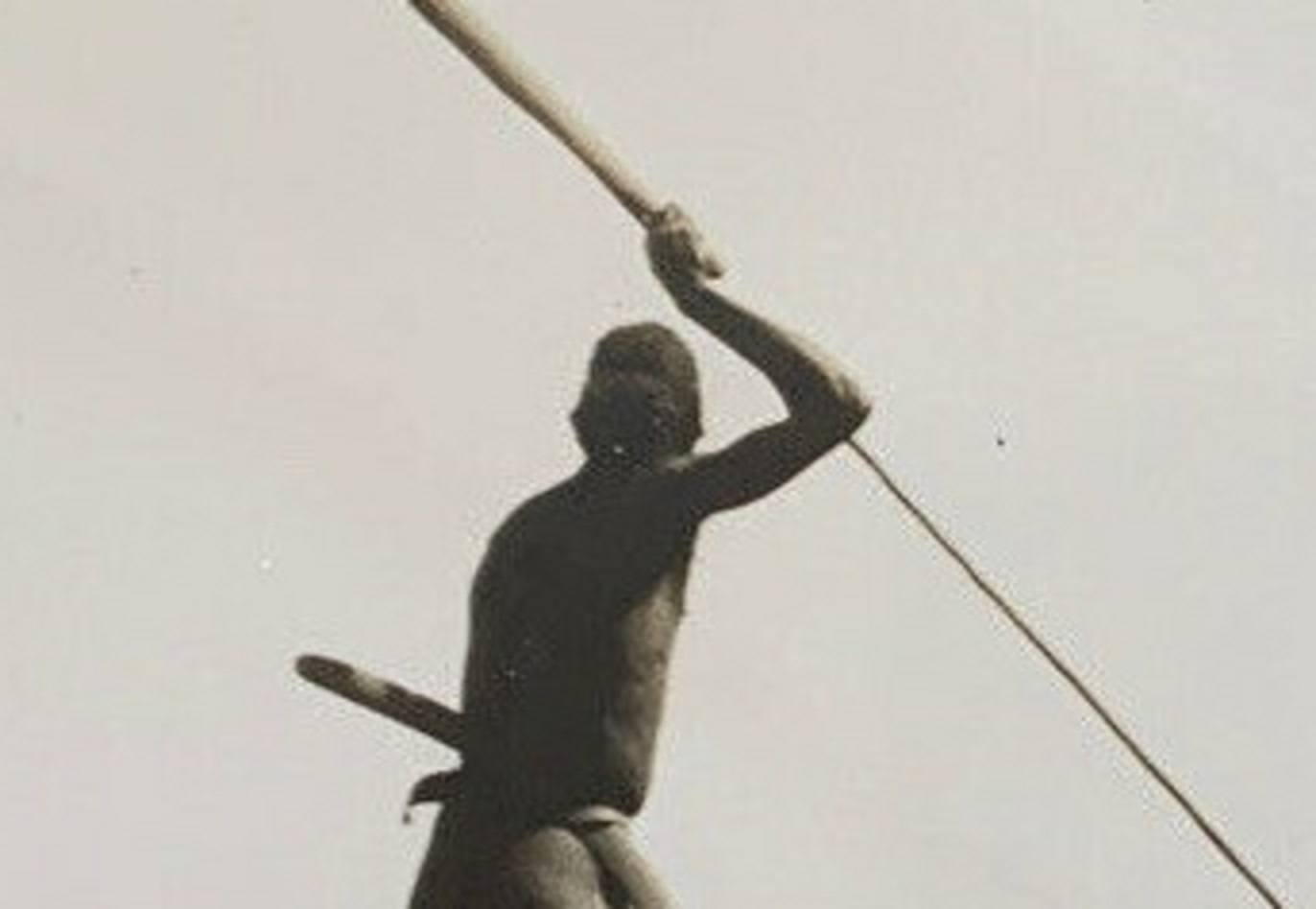

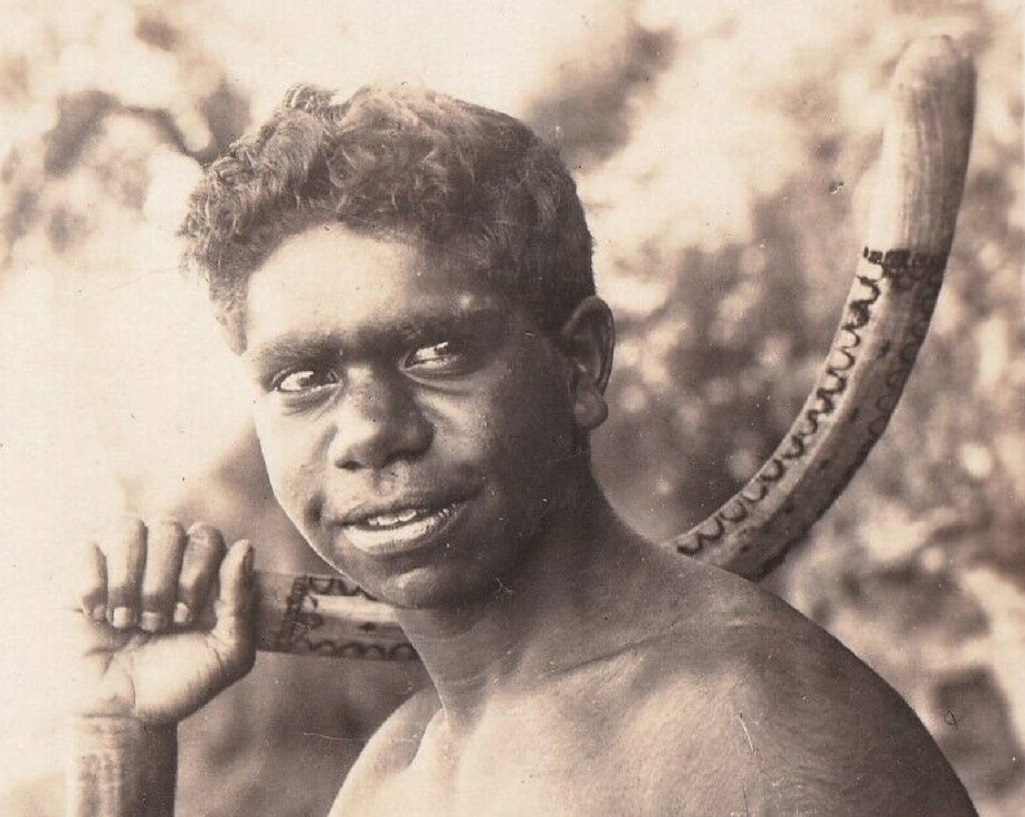

How did they hunt?

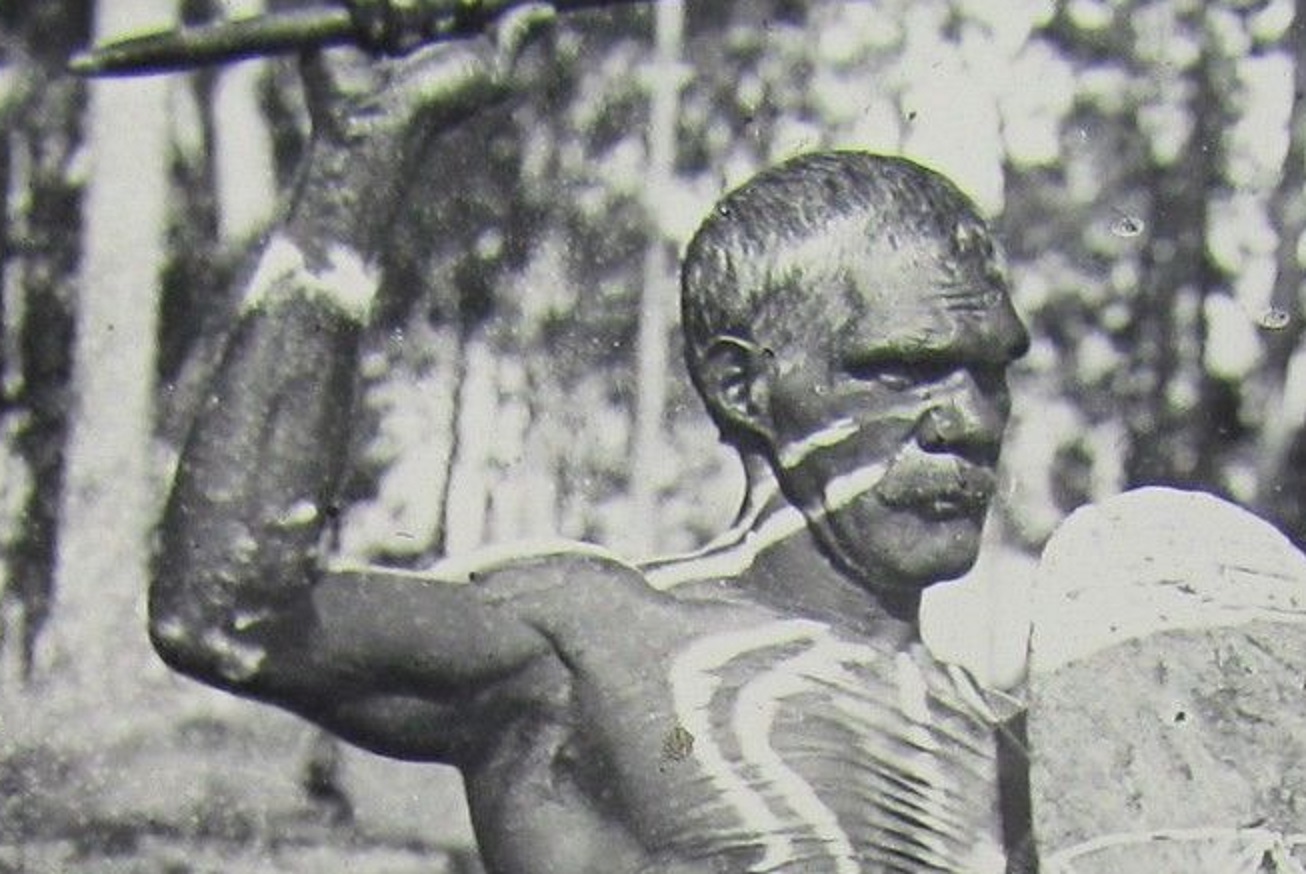

Hand-made wooden spears and spear throwers, and intricately carved boomerangs were used for hunting, as well as protection.

How did they cook?

Their animal meat was prepared by the women and cooked thoroughly over fire. They used “digging sticks” and stone-cutting tools to make their firepits and cooking utensils.

What were the women’s roles?

The women were the heartbeat of daily survival—the gatherers, the cooks, the ones who coaxed life from a harsh land. They spent long hours searching for whatever the desert was willing to give: edible plants, sweet honey, fat grubs, ants, even quick-footed lizards.

When the hunt was over, the responsibility of transforming those ingredients into a meal also fell to them. In Pintupi life, food wasn’t just gathered by women—it was shaped, prepared, and shared through their hands.

What were the men’s roles?

The men were primarily the hunters, and were tasked with tool maintenance. They created and maintained the spears and boomerangs, and built the shelters.

How did they determine land rights?

Traditionally, the Pintupi tribe claimed rights to land and resources as long as they had ties of family or friendship to the land.

Also, their birthplace, or the birthplace of their parents, established rights to use the land.

How was marriage set up?

First marriages were usually arranged by the parents. Once a man reached the marriageable age he would then travel with the camp of his prospective in-laws, contributing his hunting skills.

What happened after they married?

After they married the husband would join the camp of the wife’s parents until the birth of their first child, then they would set up their own camp.

How many wives did the men have?

Polygyny was woven deeply into Pintupi life. It wasn’t unusual for a man to take multiple wives, each one expanding the family’s circle and responsibilities. When a new wife was chosen, she stepped directly into her husband’s established camp—instantly becoming part of his world, his kinship ties, and his daily rhythms beneath the desert sun.

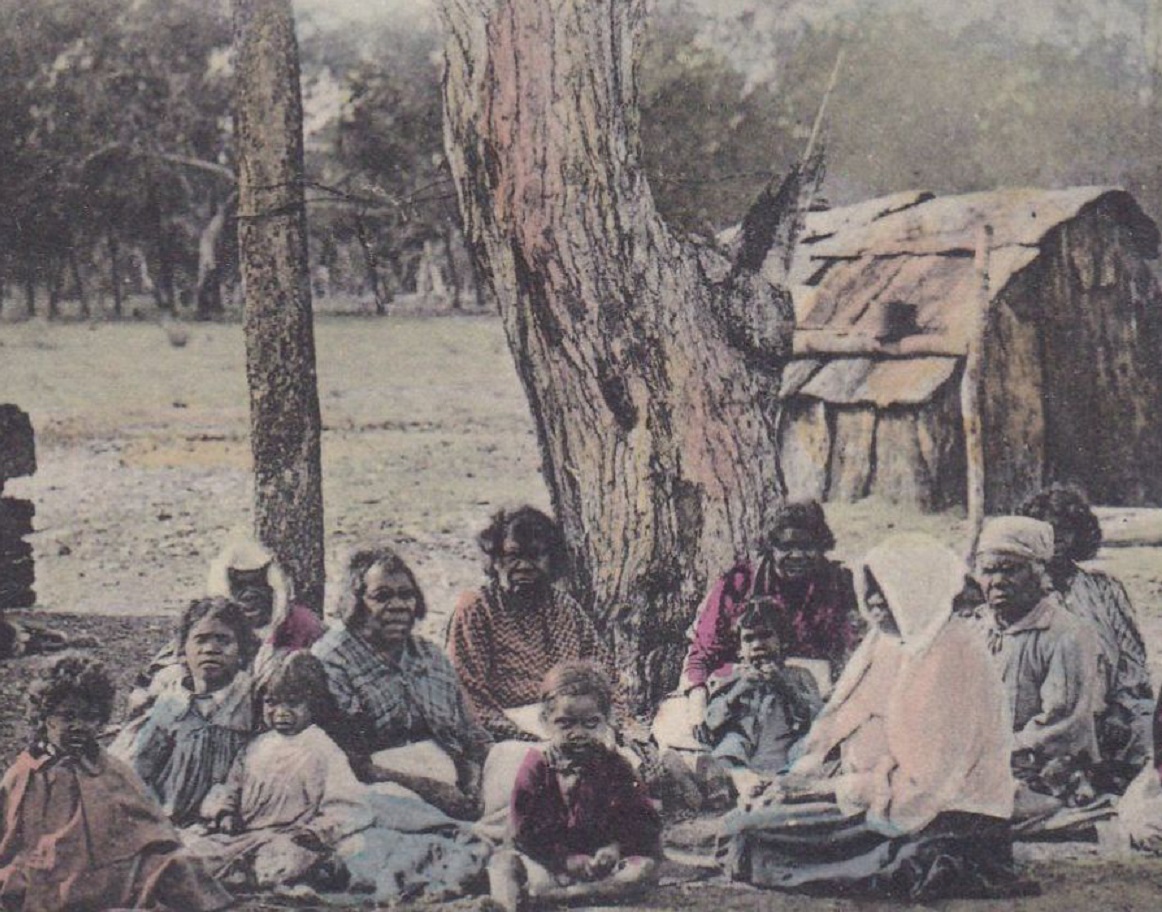

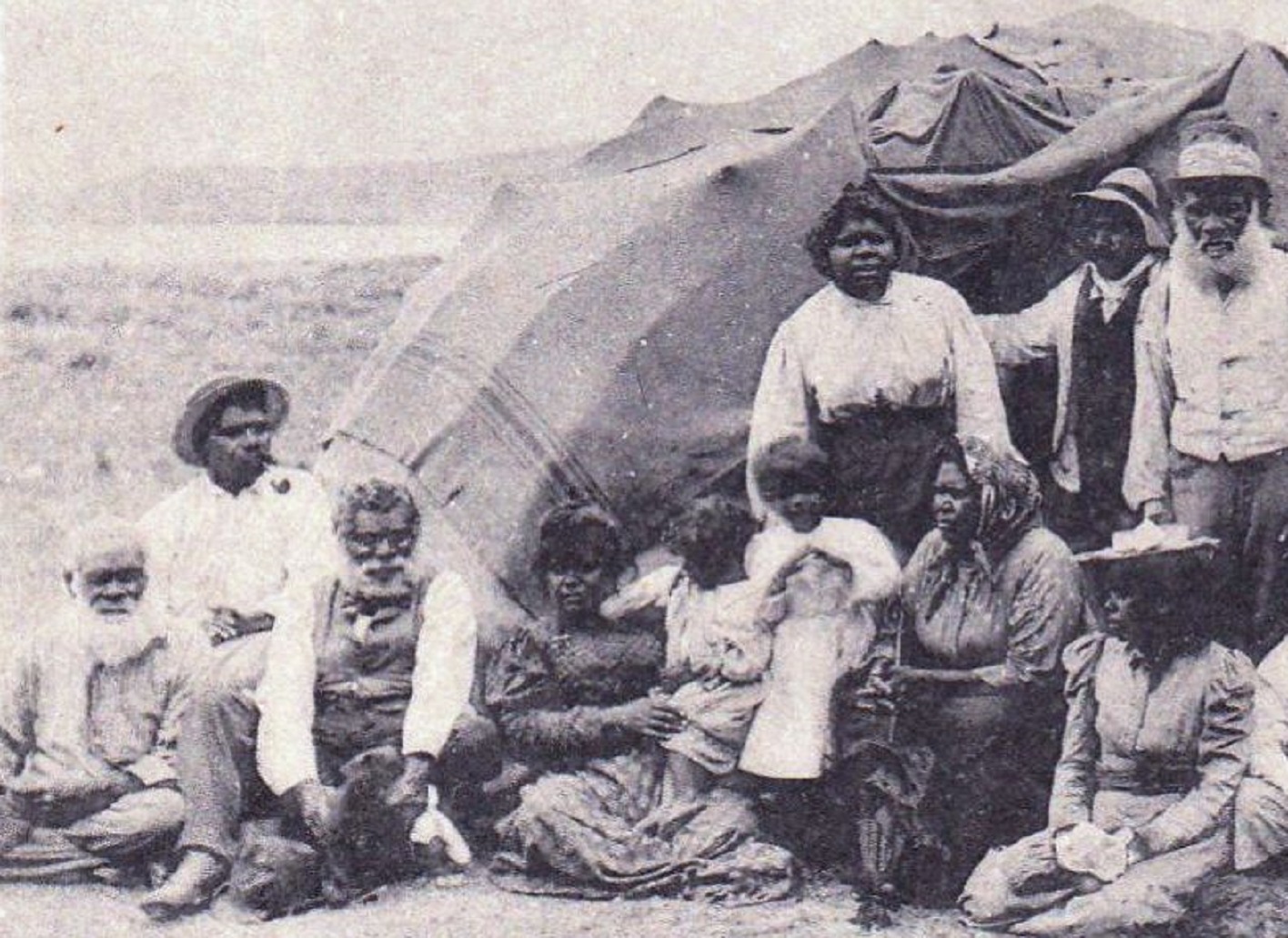

What was child rearing like?

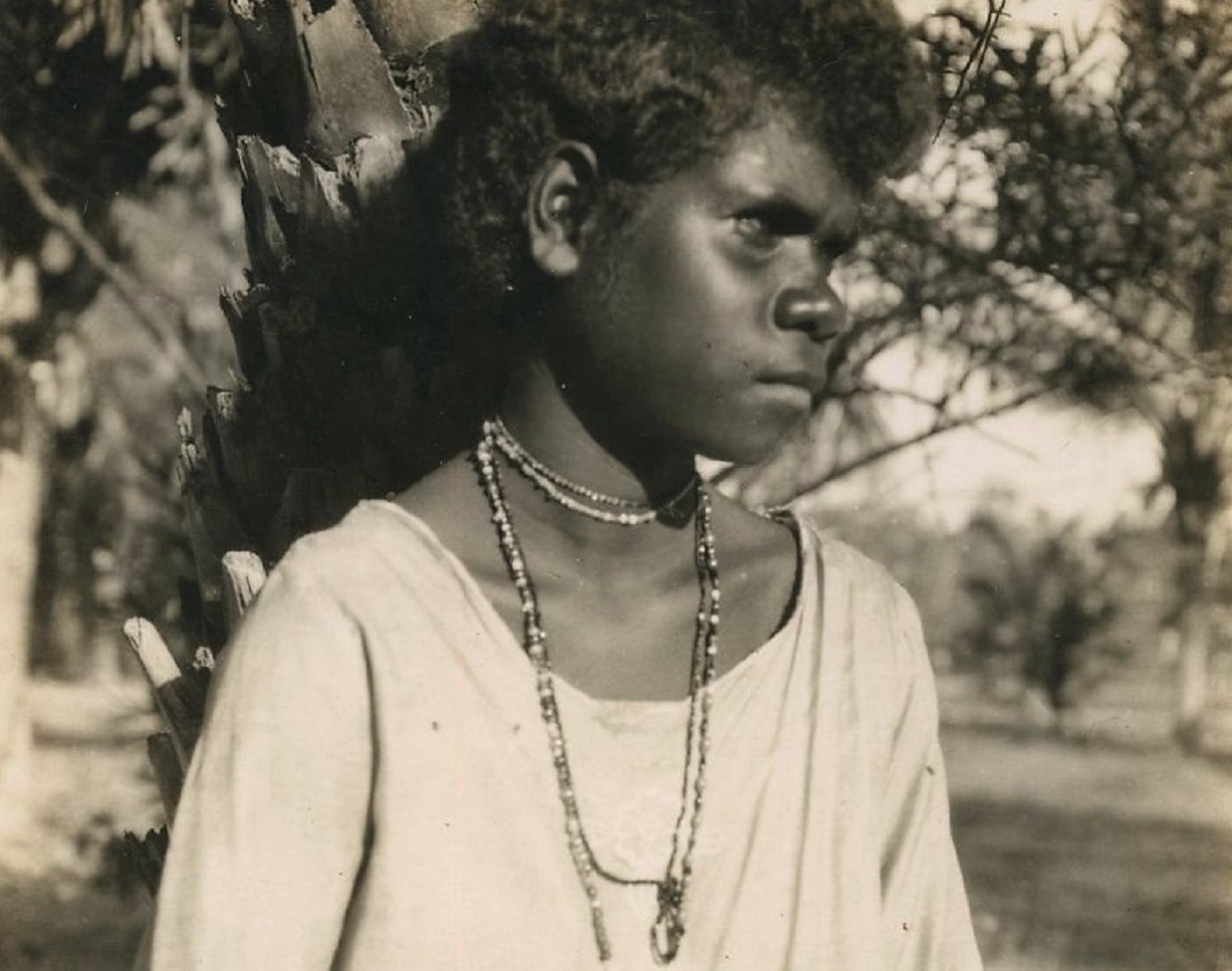

Raising the children was primarily the women’s responsibility, with co-wives taking on the task for all children born into the family unit. Kaye, (Aussie~mobs), Flickr

Kaye, (Aussie~mobs), Flickr

How were the children raised?

The children were treated as very fulfilling to the family. They were important and they were treated as such, but they were also taught early on the principles of sharing and cooperation.

What were the children’s roles?

Children, both male and female, were granted a great deal of freedom while still young. Once boys reached puberty they took part in male initiation rituals.

What was the male initiation process?

Once the young boys reached puberty they began their transformation into manhood, which involved circumcision, and ritual ceremonies.

Afterward, they were expected to start traveling to broaden social ties.

What was the female initiation process?

Girls grew up with little ceremony—at least until marriage, which often came at a young age. Only then were they ushered into the world of women’s responsibilities, taught the skills and secrets that shaped Pintupi womanhood. This transition was marked by a private ritual held solely by the tribe’s women, a sacred moment where elders passed down the knowledge that could not be spoken outside their circle.

Did they have any political organization?

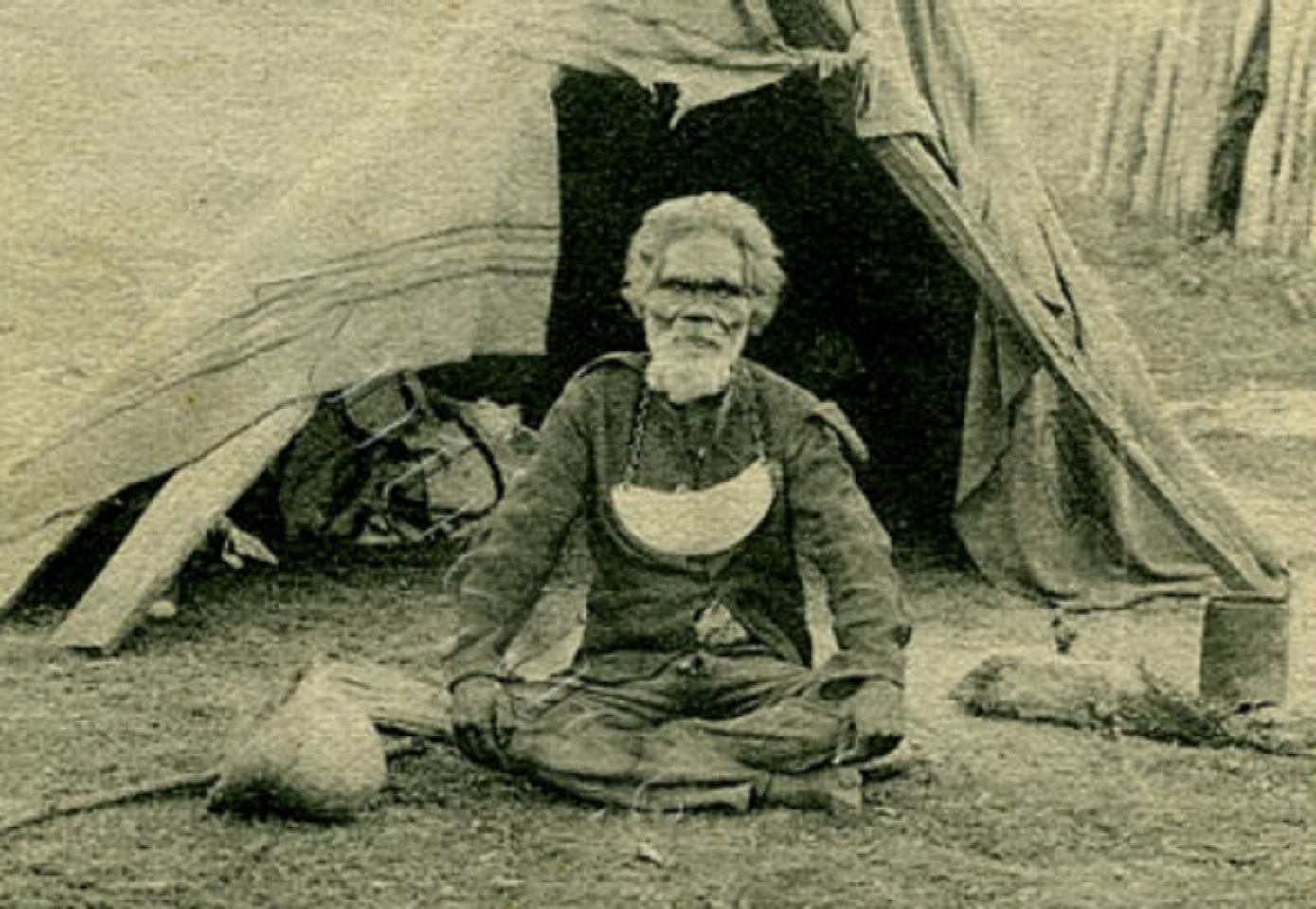

Traditional Pintupi tribes had leaders who were simply just tribe members who had a degree of experience and education through a long life.

What were the jobs of the leaders?

Few decisions in their traditional lifestyle required any sort of intervention. Leaders were primarily there to settle minor disputes and offer lifestyle suggestions.

How do they avoid conflict?

The Pintupi tribes avoided conflict simply by avoiding congregating in large groups. Since their lifestyle was nomadic, this was not a challenge. Family units stayed closely together.

But this does not mean conflict did not arise.

What sort of conflict took place?

Disputes over women were more common than anything else. In such conflicts, the angry individual would seek out their opponent and spear him in the thigh.

What were their religious beliefs?

Traditional Pintupi spirituality revolved around the “Dreaming” (tjukurrpa)—the vast, sacred tapestry that explains how the world was formed, how its laws were set, and how every creature, landscape, and person remains connected. It wasn’t just a creation story; it was the living framework that guided their entire way of life.

What is The Dreaming?

The Dreaming is both past and present. It is believed that the physical features of the world, along with the social order conducted, were created through rituals of their ancestors.

Continued traditional rituals maintain the life the ancestors built.

Do they perform ceremonies?

Various traditional ceremonies were performed in the context of initiations and the maintenance of sacred sites. Ritual secrets were passed down periodically as tribe members got older.

Did they have any ceremonial arts?

The Pintupi’s ritual practices included visual art forms, painted body art, and various dramatic songs, chants, and skits.

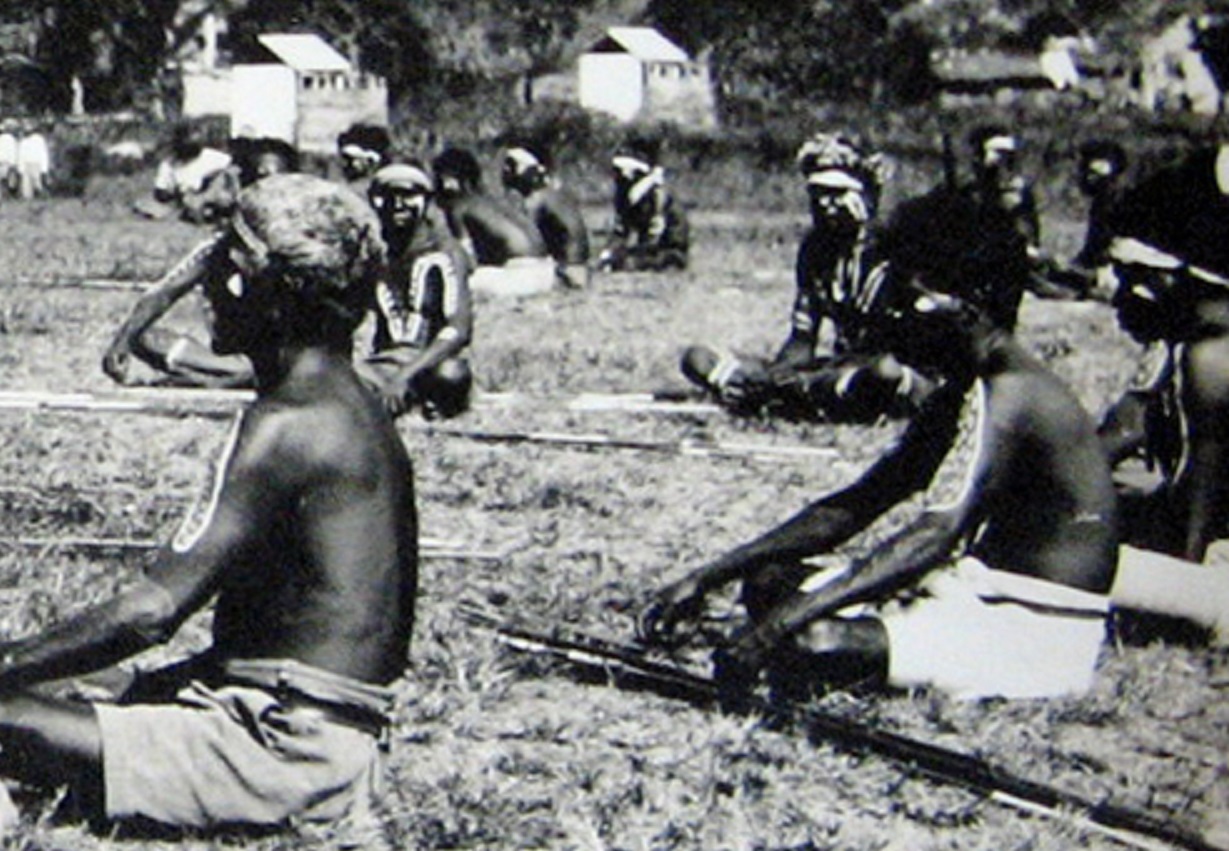

Steve Evans from Citizen of the World, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Steve Evans from Citizen of the World, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

What were their ceremonial colors?

Traditional tribal colors include red, yellow and white, and ceremonial costumes include feathers, grass, and woven materials.

Today, they have ceremonial rituals where these colors are greatly represented.

How did they medicate?

When illness struck, the Pintupi turned to their traditional healers. Curing meant a blend of powerful herbal remedies and sacred acts of sorcery—ancient practices meant to draw out sickness, restore balance, and protect the spirit as much as the body.

What happened when someone passed?

When a tribe member passed, the focus was set on the grieving survivors. The site where the passing occurred was abandoned, and the belongings of the person were distributed among close kin.

The grief though, was powerful.

How did they grieve?

The grieving family members would physically harm themselves as an expression of their grief; and “sorry fights” often occurred.

What were “sorry fights”?

Sorry fights were ritual attacks on the person’s family members for their failure to prevent the passing. Afterward, the body is taken away.

How did they handle the body?

Distant relatives were tasked with this as they believed the closer family members were too grief-stricken to carry out the process properly.

The body was buried in a sacred site determined by the elders.

What did they believe happened in the afterlife?

The Pintupi believed that a person’s spirit lingered long after the body was gone, staying close to its first resting place until a second ceremony—held months later—helped release it.

Only then was the spirit free to rise, drifting “up in the sky” to the next realm, continuing its journey beyond the world of the living.

What happened to the traditional Pintupi tribes?

At sometime during the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Australian government began testing missiles—specifically the Blue Streak missile—in the remote area where the Pintupi tribes lived.

How did the government intervene?

The government decided that the indigenous tribes had to be relocated.

They set up various settlements and began forcing the tribes to relocate, arguing that they were not ready to live in modern society and needed to be re-educated before assimilation into white society.

How did the Pintupi respond?

As a result of this forced colonization, many Pintupi tribes split up into smaller groups and fled, mostly finding refuge in the edge of the desert—which sparked the government to create numerous settlements to “catch” the fleeing tribe members.

Were the tribes completely wiped out?

Though most were eventually found and moved to the government settlements, there was one particular family unit that remained hidden in their native land—the Pintupi Nine.

How long did they survive alone?

The Pintupi Nine—still just a young family at the time—stayed tightly bound to one another, carving out their lives in the vast desert. For another ten years, they moved like shadows across the sand, keeping themselves hidden and steering clear of every trace of the modern world.

Why did they emerge?

In the early 1980’s some of the original Pintupi tribe members found a way back to their traditional lands after suffering years of colonization which resulted in numerous losses of life caused by the introduction of booze, sugar, and disease.

Did the other tribe members make it back?

As the other Pintupi tribes—who came with many modern amenities—were making their way back into their traditional lands, two members of the Pintupi Nine had noticed smoke in the distance, and wandered closer to see who had lit the fire.

Did they make contact?

Upon getting closer to the fire, the members of the Pintupi Nine considered spearing the two men (the outsiders) as they believed them to be bad people.

The outsiders considered the same thing.

Were they known to each other?

The two groups of men who were traditionally from the same tribe, did not know each other and assumed the worst. They had both claimed, “This is my country, my father passed here!”

Did conflict ensue?

The outsiders who approached them were wrapped in modern clothing and carried unfamiliar tools, while the Pintupi Nine stood nearly unclothed, gripping their traditional spears. The contrast was so stark that it left the family stunned, unsure of what kind of people they were encountering.

But as the shock faded, something else crept in—curiosity.

What did they do?

At this point, the Pintupi Nine men offered a traditional Pintupi greeting (a gentle grab of the arm), which was not known to the younger Pintupi outsider.

How did they respond?

The sudden arm grab caused instant panic and the Pintupi outsider fired his piece into the air, assuming the others were evil spirits who roamed the desert at night.

The outsiders then fled on their ATV, leaving the Pintupi Nine men both confused and afraid.

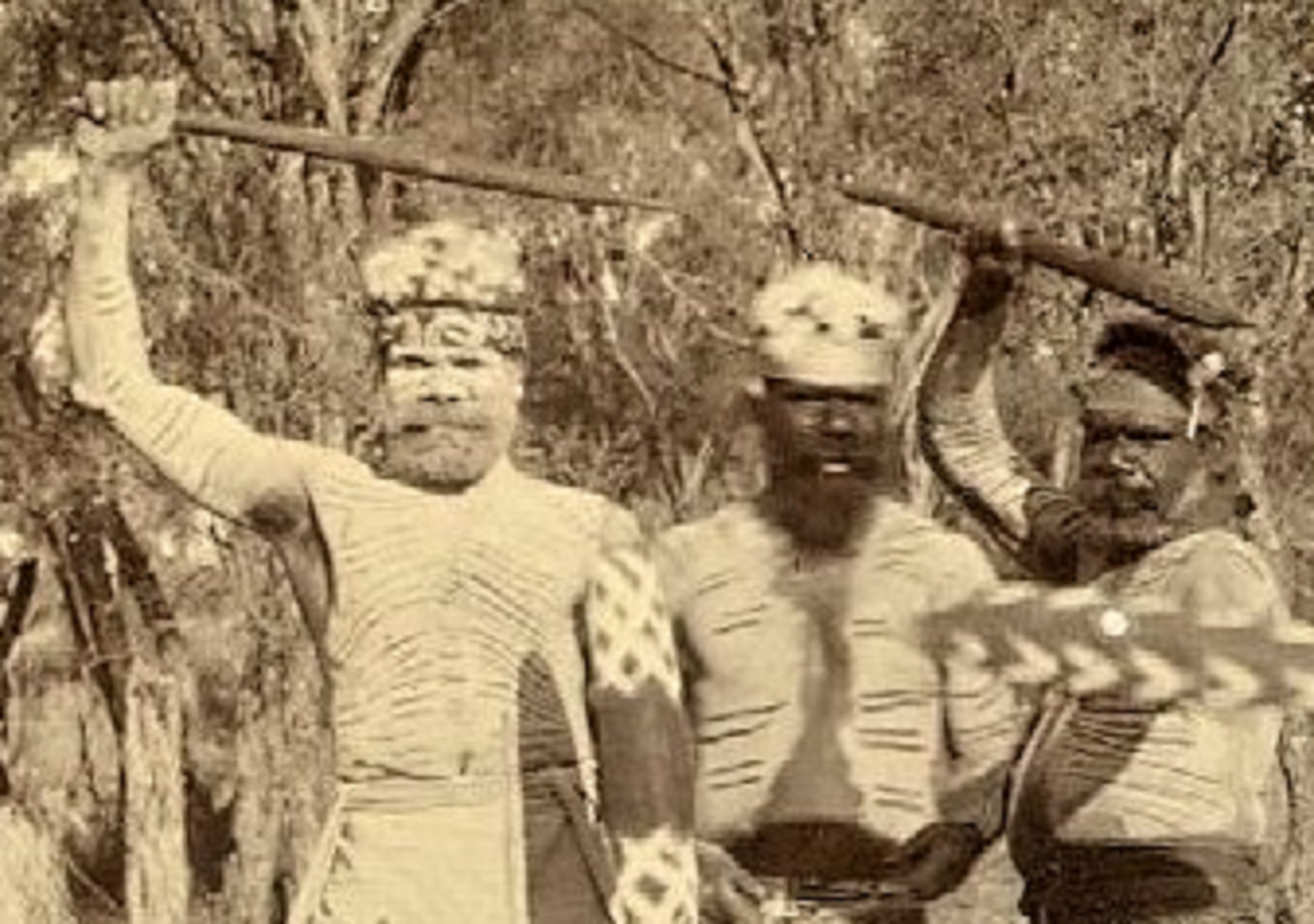

National Parks Gallery, Picryl

National Parks Gallery, Picryl

Where did they go?

The Pintupi outsiders retreated to their colonized village and told their people what they saw, describing the unclothed men and their traditional spears as “featherfoot” –a “spear man” or witchdoctor—in which young modernized Pintupi only know from folklore.

But an elder overheard, and knew exactly who they were talking about.

How did he recognize them?

The Pintupi elder, known as Freddy West, had known the Pintupi Nine family well from pre-contact times.

What did they know about them?

Over the years, elders had quietly discovered footprints and abandoned fire pits out in the desert—small but unmistakable signs that the hidden family, their own blood relatives, were still out there. These clues became whispered proof that the lost Pintupi were alive, surviving in silence just beyond reach.

What did they refer to them as?

The group had referred to the Pintupi Nine as “the lost ones”: a group of the original Pintupi tribe who had never come in with the rest.

How did they respond?

Motivated by pity, and a desperate need to freshen up the gene pool, Freddy West and the other village leaders made the decision to find the “lost” group and bring them in to their village.

Where did they go?

Freddy West and his people had set off to a neighboring colonized Pintupi village to inform them of their findings.

In doing so, they informed someone else.

Who did they tell?

Along the way, they met NT welfare officer Jeremy Long, who was on an expedition to “check on” any remaining Pintupi nomads. Freddy West told the officer about the family who had chosen to remain hidden.

Officer Long brought in Aboriginal Affairs to aid in the search.

How did they find them?

The elders organized a small search party, climbing into motorized vehicles and following the faint trail of footprints across the desert. Step by step, track by track, they closed in—until at last, they caught up with the elusive Pintupi Nine.

What did they do?

Upon finding the group’s camp, they assumed they’d be met with fear, so they undressed themselves before approaching, thinking this would help build trust.

How did the Pintupi Nine react?

Upon approaching, the Pintupi Nine were undoubtably afraid. What was meant to be a peaceful choice, became similar to a kidnapping scene out of a horror movie.

The Pintupi Nine ran around scared as the outsiders grabbed onto them to keep them from leaving.

Why did they run?

The two Pintupi Nine members who had previously met the outsiders were angry as they now knew they were being followed. They knew of the white colonization and had been spending many years avoiding it.

At this point, they knew it was over.

What did the outsiders do?

The Pintupi outsiders attempted to tell the lost group that they had been “living in the bush for too long” and that they were family and should be trusted. They used familiar tribal names to gain recognition.

The Aboriginal Affairs people made a phone call, and the Pintupi Nine were given a choice.

What was their choice?

The Pintupi Nine were apparently given the choice to stay “in the bush” or to go with the others and join their colonized village.

What did they choose?

With the obvious presence of motorized vehicles, clothing, and containers filled with clean water—the Pintupi Nine felt pressured to agree and go back with them.

They set down their spears and put their hands up to surrender.

Where did they go?

The Pintupi Nine reluctantly boarded the vehicles and were taken back to the Pintupi village of Kiwikurra—which was as remote as could be, but still very modernized.

What did they find?

The Pintupi Nine experienced immense culture shock. But before discovering modern amenities, they discovered something else that made them both angry and relieved—a long lost loved one.

Who did they find?

Years prior, after the passing of the family’s patriarch, the Pintupi Nine met with a single nomadic Pintupi man who offered to marry one of the daughters and take her to safety.

That daughter agreed, and promised to come back and find her family—but she never returned.

What did they do?

It had been 22 years since the Pintupi Nine had seen this girl, who was now an adult woman. The siblings raged and attacked her for giving up on them.

As soon as everyone calmed down, their perspective changed greatly.

Did they adapt?

At first, a few of the Pintupi Nine members refused blankets and food, trying desperately to avoid joining the modern world, even though the others were indulging without guilt.

But once they were introduced to sugar, they couldn’t get enough.

Did they stay in the village?

It was only days later when Aboriginal Affairs broke their silence of what they found. And although they had to keep certain things a secret to protect the Pintupi tribes as a whole, the story didn’t take long to erupt.

More and more people showed up for various reasons.

What was happening in the village?

The modern Pintupi village of Kiwikurra was now being visited by various doctors, anthropologists, journalists, and anyone else who wanted a slice of this breaking news story.

This led to a serious infection where all nine of the newcomers became seriously ill.

How did the world respond?

As the story gained international coverage, people from all over the globe responded in outrage. Letters from all over the globe came flooding in accusing the government of forcibly taking the Pintupi Nine from their home, causing their impending demise.

Did the Pintupi Nine survive?

Yes, thankfully they all survived the illness after being given medical treatment. They remained in the village, learning a new way of life—well, except for one of them.

Where did they go?

One of the Pintupi Nine chose not to stay. In fact, the young man simply got up and walked off into the desert without saying a word to anyone. Someone followed for as long as they could until they gave up and turned back.

Why did he leave?

It is believed that the Pintupi Nine were so peaceful that they had very little experience with conflict. So, when one of the sisters was instantly married to another village man, conflict ensued.

Why was there conflict?

The sister was married to a village leader, but she had fancied someone else, which led to a very public spear-brandishing between the two men.

This was traumatizing for the members of the Pintupi Nine—specifically the one who then chose to leave.

Thomas Dick, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Dick, Wikimedia Commons

Where are they now?

The rest of the Pintupi Nine stayed in the village for many years until flooding in 2001 forced them to move to other, more modern settlements where they experienced violence, substance misuse, and many ended up locked up.

Did they all survive?

The two mothers had passed. One back in 1998 from renal failure and the other shortly after the flooding from an unknown illness.

Both had experienced inadequate care before succumbing to their illnesses.

Where did the rest of them end up?

Years after the flood, the village of Kiwirrkurra was reestablished and Pintupi tribe members from various settlements made their way back—accumulating a population of close to 150 today.

Five of the six surviving Pintupi Nine still live in Kiwirrkurra—reaping the benefits of modern society.

What are they known for?

In fact, several of the family members have been recognized for their artistic talent, and now profit off of their traditional art forms as budding artists and teachers.

Do they remember their old life?

The Pintupi Nine very much remember their old life and think of it fondly.

Although they are now enjoying life in the modern world, they very much miss their traditional lifestyle and have said that they’d go back if given the opportunity.