Ancient American brilliance that colonists never understood

Archaeologists keep uncovering structures and systems that disrupt long-held assumptions about early America. These achievements weren’t improvised or accidental; they were engineered with calculation and purpose in ways European settlers failed to grasp.

Cahokia’s Monks Mound

Rising above Illinois’s landscape, Monks Mound represents a monumental earthwork built through coordinated labor and deliberate soil layering. Its immense footprint signals organized leadership and careful planning. Archaeologists view it as evidence of a society capable of complex engineering and long-term vision, qualities early colonists underestimated or ignored.

Clarinetguy097, Wikimedia Commons

Clarinetguy097, Wikimedia Commons

Mesa Verde Cliff Dwellings

Europeans initially misunderstood the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings. Set within sheltered alcoves, the natives used stone masonry, ventilation openings, and strategic placement to moderate temperature year-round. Their multistory layouts reflect planning suited to defense and community organization.

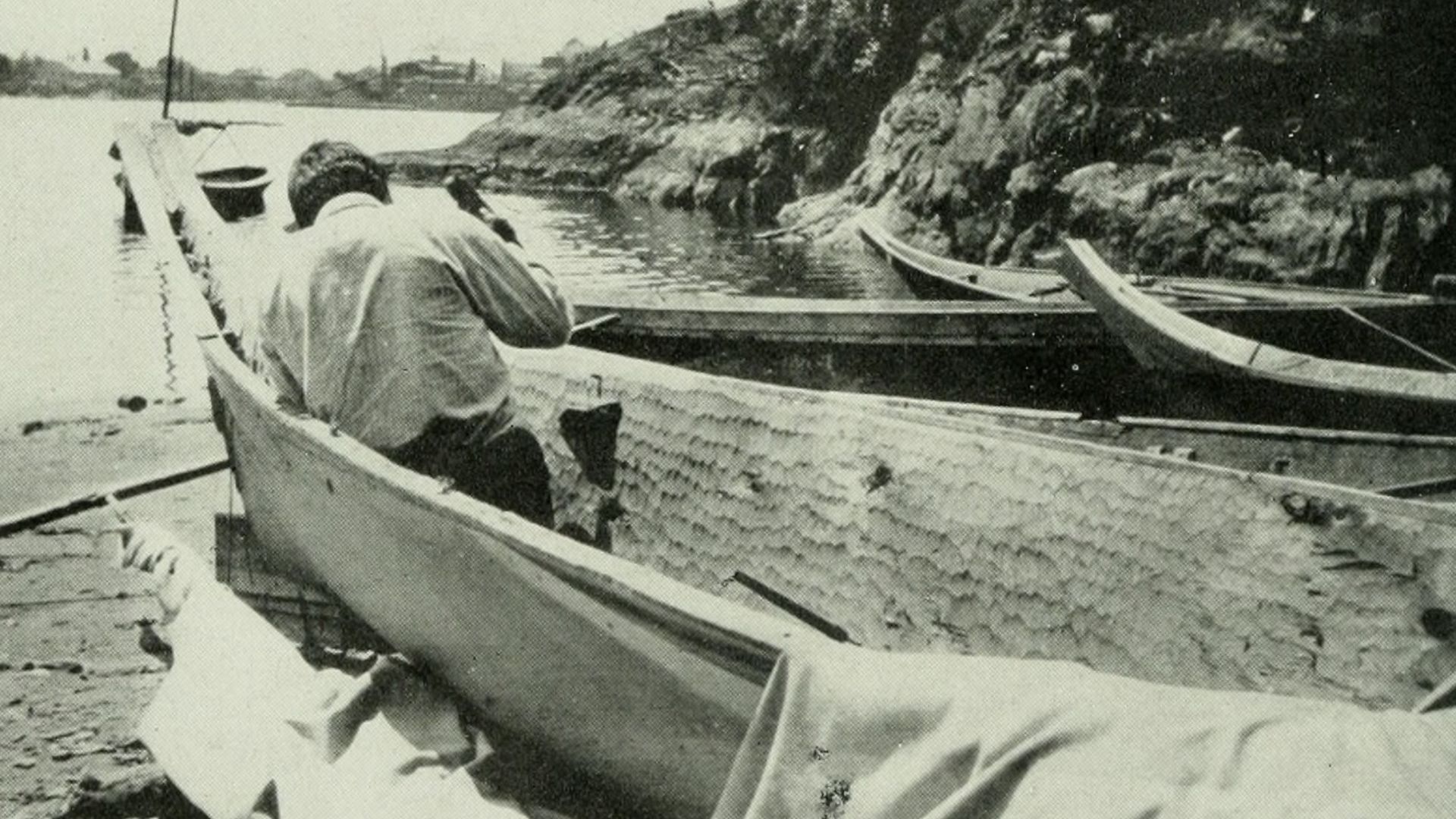

Arctic Kayaks And Umiaks

Kayaks and umiaks drew little serious attention from colonists, yet their lightweight frames and waterproof coverings represented finely tuned marine engineering. Each vessel balanced speed and maneuverability in freezing waters. Their construction illustrates a long tradition of innovation shaped by climate and precise material understanding.

Fridtjof Nansen, Wikimedia Commons

Fridtjof Nansen, Wikimedia Commons

Serpent Mound

Archaeologists now interpret the Serpent Mound as evidence of symbolic engineering linking the environment, observation, and ceremony in ways early colonists neither recognized nor recorded accurately. Stretching across an Ohio ridge, it followed a curving form aligned to celestial events, including solstice sunsets.

Chaco Canyon Great Houses

Chaco Canyon’s great houses reveal architectural planning on an impressive scale, with multistory rooms and plazas aligned to solar and lunar cycles. Roads radiated outward in straight lines. Excavations show coordinated labor and standardized masonry, countering early narratives.

James Q. Jacobs, Wikimedia Commons

James Q. Jacobs, Wikimedia Commons

Chaco Canyon’s Sun Dagger

At Fajada Butte, the Sun Dagger marks solstices and lunar standstills through beams of light crossing carved spirals. Its precision comes from the intentional placement of rock slabs, not chance. The feature demonstrates detailed astronomical tracking, a skill colonial writers rarely acknowledged.

Greg Willis from Denver, CO, usa, Wikimedia Commons

Greg Willis from Denver, CO, usa, Wikimedia Commons

Tulum’s Coastal Observatory

Connecting cosmology and a coastline settlement into a unified design, Tulum’s round tower stands along Mexico’s Caribbean coast with openings said to be oriented toward equinox sunrise. Its design suggests purposeful monitoring of celestial events that guided ritual and seasonal decisions.

Popo le Chien, Wikimedia Commons

Popo le Chien, Wikimedia Commons

Inca Terracing Systems

Today’s visitors to the Sacred Valley encounter terraces that appear scenic, yet each platform functions as a controlled agricultural zone. Retaining walls, drainage layers, and varied elevations created microclimates for diverse crops. Spanish chroniclers rarely understood the system’s technical depth, leaving later researchers to document its precision.

ErnestoTalav.Montoya, Wikimedia Commons

ErnestoTalav.Montoya, Wikimedia Commons

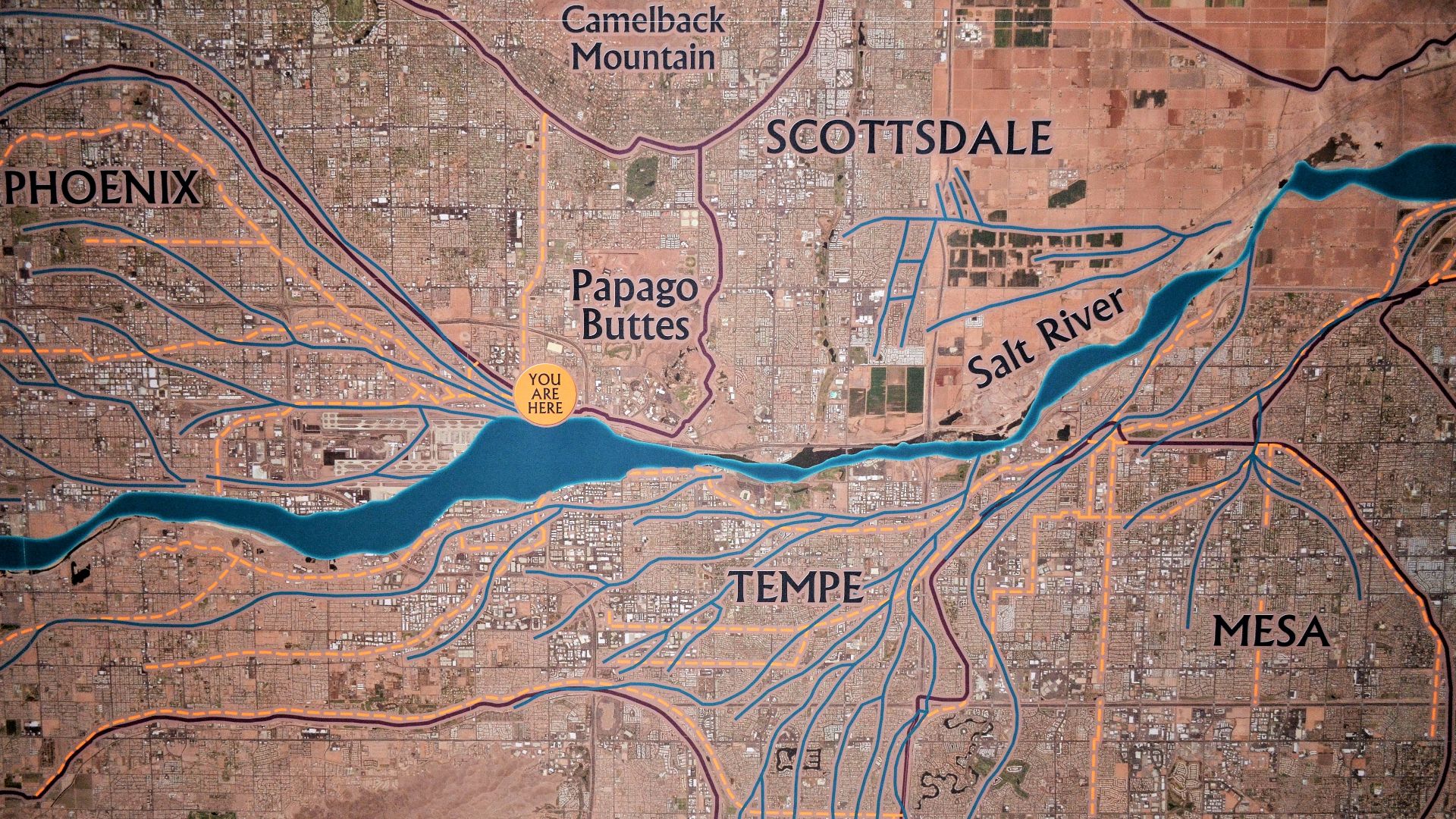

Hohokam Canal Network

The Hohokam constructed hundreds of miles of canals across Arizona’s desert, maintaining consistent gradients that carried water to expansive fields. Sediment profiles show repeated widening and realignment over centuries. Colonists failed to understand the system’s sophistication, yet archaeologists see one of North America’s most enduring examples of large-scale hydraulic engineering.

Scotwriter21, Wikimedia Commons

Scotwriter21, Wikimedia Commons

Cahokia’s Woodhenge

Set within Cahokia’s broader cultural center, Woodhenge functioned as a precisely arranged calendar marking seasonal sun movements. Each post’s placement reflects careful observation rather than coincidence. Researchers see it as firm proof of advanced astronomical knowledge.

James Q. Jacobs, jqjacobs.net, Wikimedia Commons

James Q. Jacobs, jqjacobs.net, Wikimedia Commons

Poverty Point Earthworks

Across northeastern Louisiana, Poverty Point’s curving ridges and towering mounds reveal intensive soil movement and striking geometric planning. Built around 1400 BCE, the complex required coordinated labor on a scale early European writers claimed Indigenous groups couldn’t achieve.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/15308454@N06/ Kniemla, Wikimedia Commons

https://www.flickr.com/photos/15308454@N06/ Kniemla, Wikimedia Commons

Mound City Group Geometry

Geometry becomes unmistakable at the Mound City Group, where Hopewell builders created circles, squares, and broad alignments across Ohio’s terrain. Measurements show consistent ratios that point to shared mathematical practices. These patterns challenge colonial assumptions about Indigenous knowledge.

Newark Earthworks Great Circle

At Newark, the Great Circle stretches across an immense enclosure whose entrances and earthen walls align with ceremonial and astronomical principles. Surveyors note the precision embedded in its layout, which highlights abilities colonial observers overlooked. Its scale shows a community capable of mobilizing labor and integrating cosmology into engineered spaces.

Hohokam Check Dams

Built across desert washes, Hohokam check dams slowed runoff, captured sediment, and directed water to nearby planting zones. Their placement reflects close observation of flood behavior and soil movement. These small but effective structures allowed steady food production in arid terrain.

Don Lancaster and Dr. James Neely, Wikimedia Commons

Don Lancaster and Dr. James Neely, Wikimedia Commons

Ancestral Puebloan Reservoirs

Many early colonists assumed desert communities relied solely on scarce streams, yet excavations at Chaco and Mesa Verde revealed engineered reservoirs that captured rain and runoff. These basins used plastered surfaces and designed inlets, allowing settlements to thrive in unpredictable climates.

Taino Raised Field Agriculture

Archaeologists studying Caribbean sites uncovered Taino raised fields, a discovery that challenged long-held assumptions about limited Indigenous farming systems. These elevated plots improved drainage and soil structure in tropical conditions. Their patterned layouts demonstrate environmental engineering that sustained large communities.

Khajitdadddy, Wikimedia Commons

Khajitdadddy, Wikimedia Commons

Aztec Chinampa Floating Gardens

Visitors to the Valley of Mexico often misinterpret chinampas as natural islands rather than engineered agricultural platforms. Excavations and colonial descriptions reveal layered sediments, boundary stakes, and stabilizing willow trees that created highly productive fields. Their efficiency supported dense populations and showed a level of agricultural planning Europeans struggled to match.

Karl Weule, †1926, Wikimedia Commons

Karl Weule, †1926, Wikimedia Commons

Maya Puuk Region Chultunes

In regions without rivers, Maya builders carved chultunes into limestone bedrock and turned natural geology into water-storage systems. Their bottle-shaped forms and plaster lining indicate careful design for filtration and preservation. Recognition of these features grew as archaeologists mapped settlement patterns.

Magister Mathematicae, Wikimedia Commons

Magister Mathematicae, Wikimedia Commons

Inca Qocha Reservoir Systems

Interest in high-altitude agriculture expanded when researchers documented Inca Qocha reservoirs across Peru’s puna grasslands. These engineered basins regulated water release, reduced frost risk, and supported seasonal herding routes. Their design contradicts colonial claims that Andean communities lacked large-scale environmental planning.

Yuraq-yaku1, Wikimedia Commons

Yuraq-yaku1, Wikimedia Commons

Mississippian Causeways

Across major Mississippian centers, raised causeways connected plazas and platform mounds in deliberate, structured layouts. Their height protected travelers during seasonal flooding and guided ceremonial movement. Excavations show they were engineered features rather than incidental paths.

A. E. Crane, U.S. Department of Transportation, Wikimedia Commons

A. E. Crane, U.S. Department of Transportation, Wikimedia Commons

Northwest Coast Dugout Canoes

Cedar dugout canoes from the Pacific Northwest highlight a level of craftsmanship that early European visitors struggled to recognize. Builders shaped massive logs into balanced, hydrodynamic hulls capable of handling open ocean conditions. These vessels supported trade, travel, and cultural exchange.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Iroquois Longhouse Architecture

Longhouses encountered by early settlers were often mischaracterized as simple shelters, but archaeological and ethnographic work reveals structured ventilation and insulation suited to cold winters. Their elongated design supported extended households while maintaining interior comfort, reflecting a domestic architecture based on adaptation and communal living patterns.

Jaro Nemcok, Wikimedia Commons

Jaro Nemcok, Wikimedia Commons

Inca Suspension Bridges

Reports from early Spanish chroniclers sometimes described Inca suspension bridges with disbelief, assuming woven cables could not support travelers. Modern studies confirm their strength came from braided plant fibers, careful anchoring, and regular community renewal. These bridges connected remote regions and showed engineering that blended materials science with shared civic responsibility.

Aga Khan (IT), Wikimedia Commons

Aga Khan (IT), Wikimedia Commons

Southwest Desert Passive Cooling House Design

Across the arid Southwest, builders used thick adobe walls and strategic orientation to moderate indoor temperatures in ancient cities long before refrigeration existed. These choices created cooler interiors through thermal mass and airflow management. Early colonists missed the deliberate engineering behind climate-responsive homes designed for comfort.

English: NPS Photo, Wikimedia Commons

English: NPS Photo, Wikimedia Commons

California Water-Stone Milling Technology

Bedrock mortars scattered across California’s foothills show a milling system that early settlers interpreted as rudimentary, yet archaeological studies show carefully chosen grinding surfaces positioned near water sources. These features supported large acorn-processing economies for food preparation that balanced efficiency and knowledge of local plant behavior.