The Cherokee

The Cherokee Indians have a rich and complex history in the United States. They were a sophisticated society with a unique language, governance structure, and cultural practices. But when settlers encroached on their land they were met with devastating consequences.

The forced relocation known as the Trail of Tears resulted in the displacement and deaths of thousands of Cherokee people.

Despite this trauma, the Cherokee Nation persevered, rebuilding their community and becoming one of the most successful and influential Native American tribes in the United States.

From their traditional roots to their modern day wins, this is their story.

Who are they?

The Cherokee Indians are the largest Native American group in existence. They originated from the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States.

Traditional Cherokee Language

The Cherokee language is part of the Iroquoian language group—a language family of Indigenous peoples of North America.

As of 2020, almost all surviving Iroquoian languages are severely or critically endangered, with some languages having only a few elderly speakers remaining—the Cherokee language being one of them.

Today, most of the Cherokee speak English.

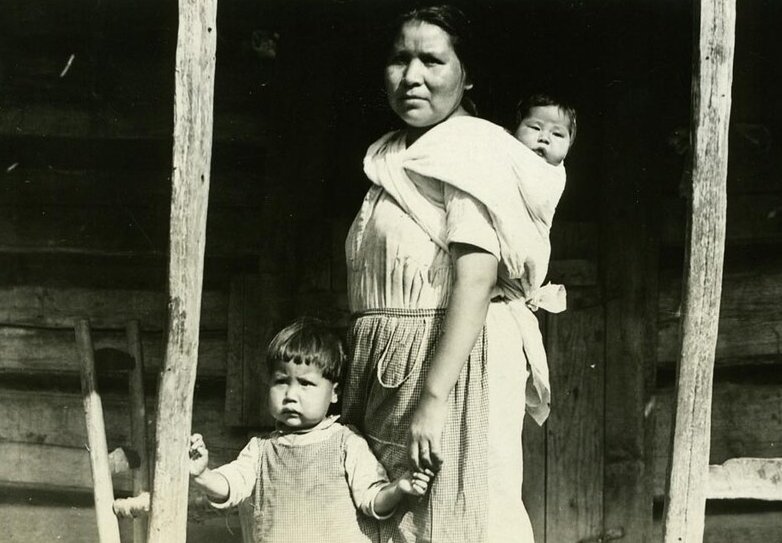

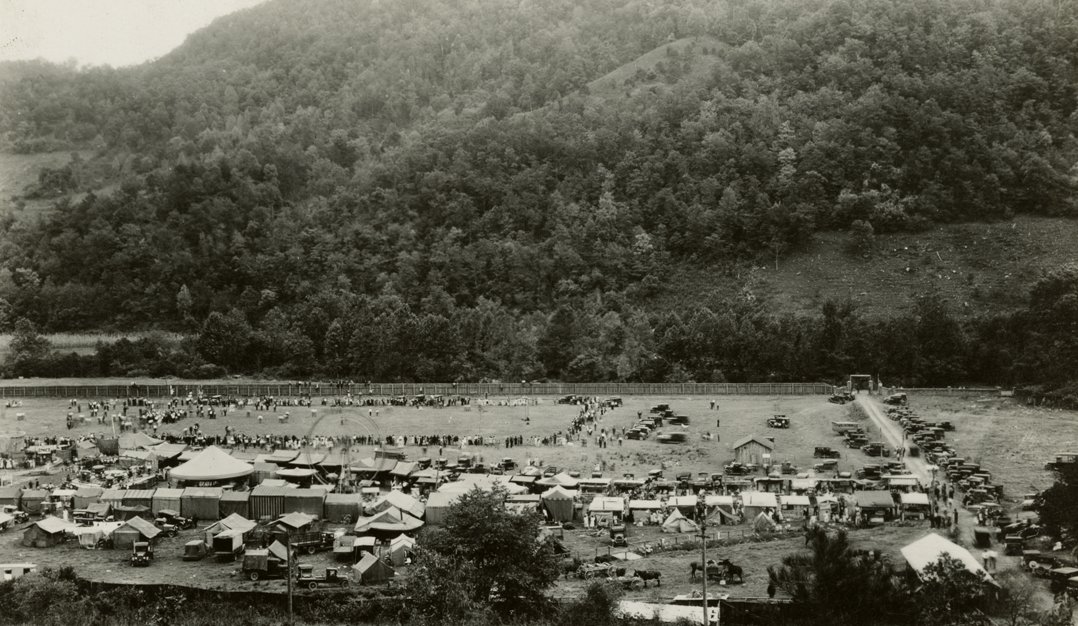

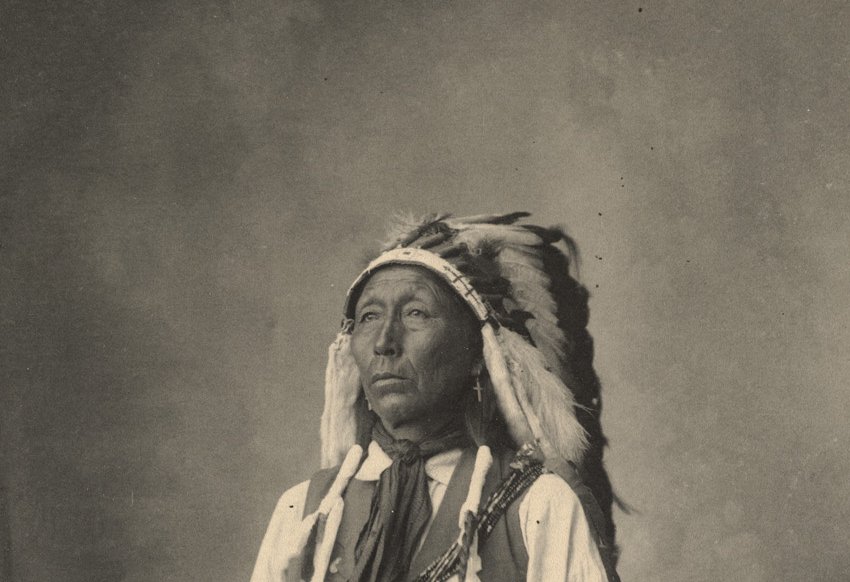

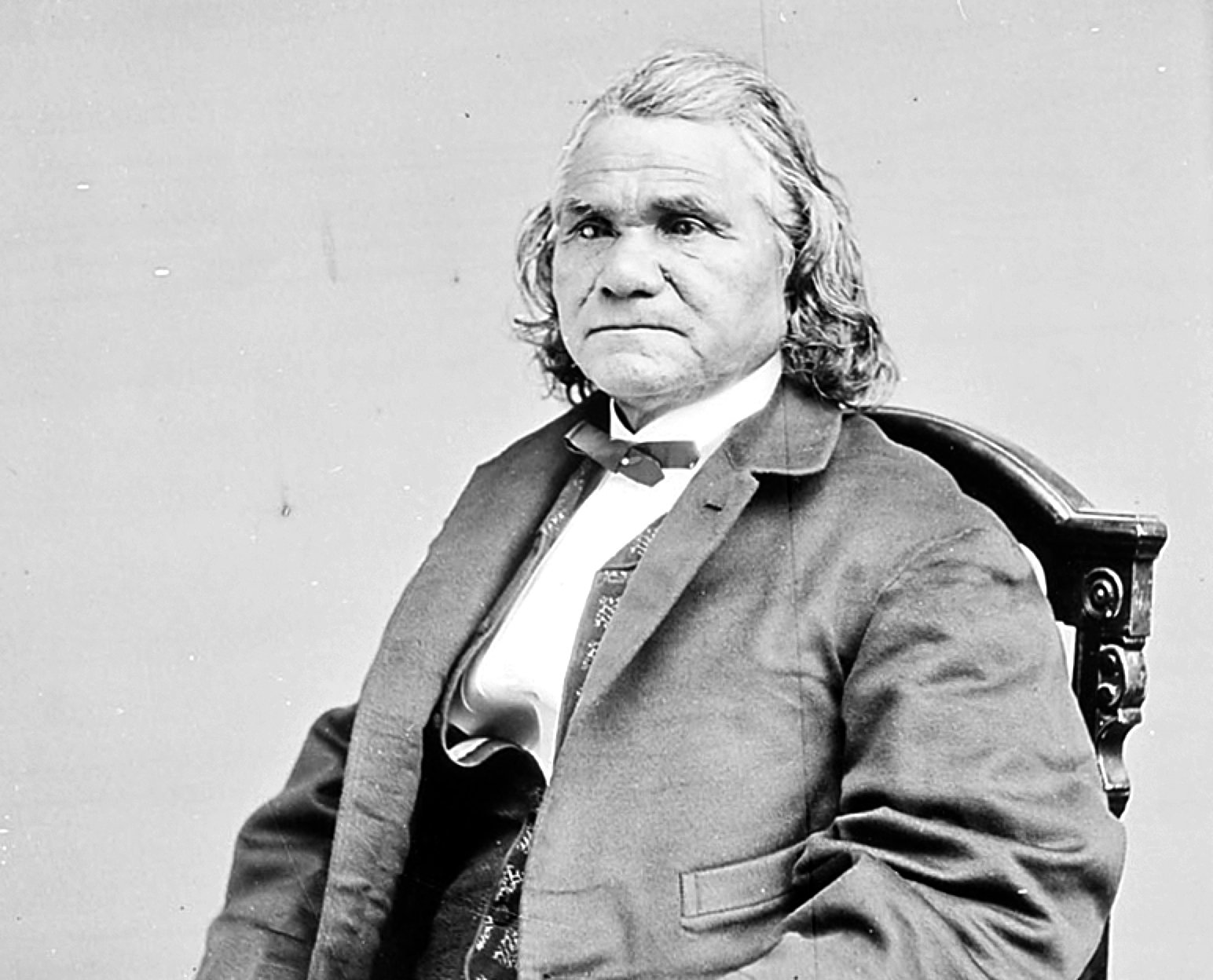

State Archives of North Carolina Raleigh, Wikimedia Commons

State Archives of North Carolina Raleigh, Wikimedia Commons

Name Meaning

Their name is derived from a Creek word meaning “people of different speech”; many prefer to be known as Keetoowah or Tsalagi.

Traditional Homelands

Prior to the 18th century, the Cherokee were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern North Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, edges of western South Carolina, northern Georgia and northeastern Alabama consisting of around 40,000 square miles.

Homelands Today

Today, three Cherokee tribes are federally recognized: the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians (UKB) in Oklahoma, the Cherokee Nation (CN) in Oklahoma, and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) in North Carolina.

Nearly half of the Cherokee Nation today live within the reservation boundaries in northeastern Oklahoma.

Population

The Cherokee Nation is the largest tribe in the United States with more than 450,000 tribal citizens worldwide. More than 141,000 Cherokee Nation citizens live on the reserves in Oklahoma.

Even back in 1650, the tribe numbered some 22,500 individuals and controlled about 40,000 square miles of the Appalachian Mountains.

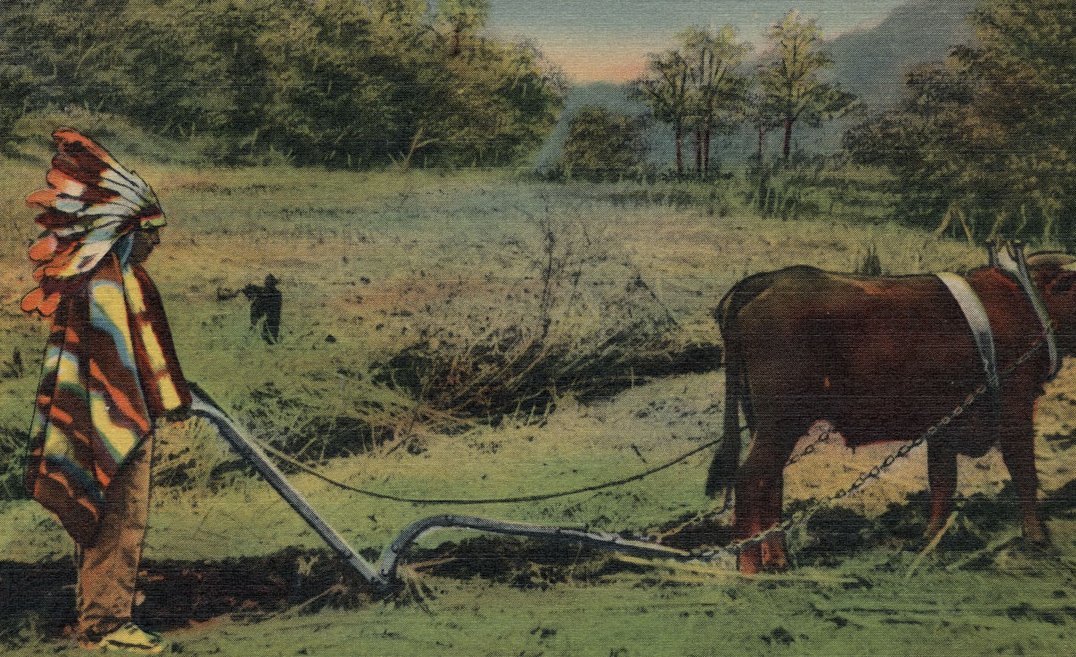

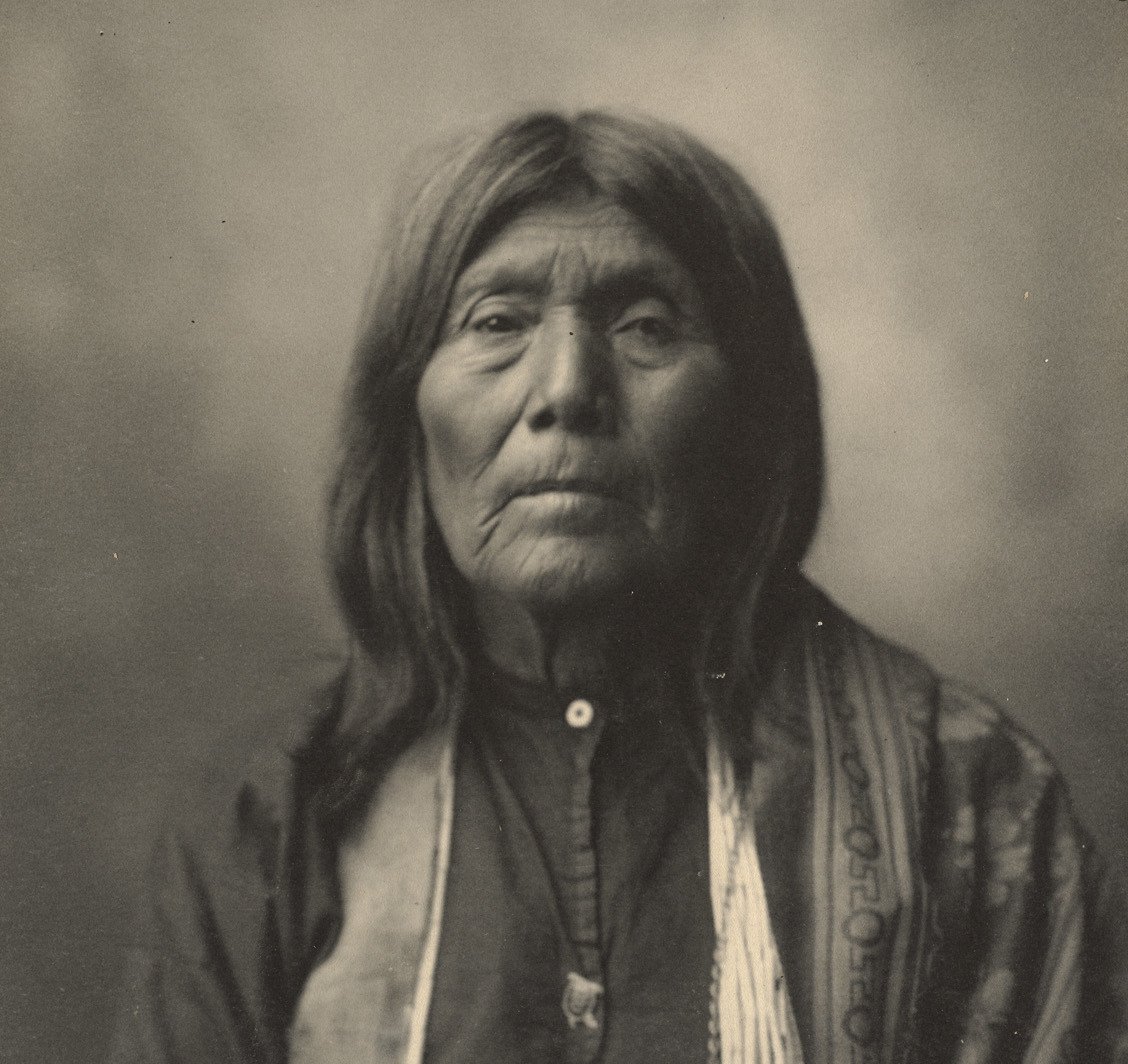

Sogospelman, Wikimedia Commons

Sogospelman, Wikimedia Commons

The Five Tribes

By the 19th century, White American settlers had classified the Cherokee of the Southeast as one of the "Five Tribes" in the region, which also included the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminoles.

These tribes were grouped together

Agrarianism

The Cherokee were included in The Five Tribes because they practiced agrarianism—a social culture that promotes subsistence agriculture, family farming, widespread ownership, and political decentralization.

They also lived in permanent villages and had begun to adopt some cultural and technological practices of white settlers.

Cherokee Villages

The Cherokee traditionally lived in small permanent villages, usually located in fertile river bottoms. Houses were built relatively close together, and each village had a council house where ceremonies and tribal meetings were held.

Many Cherokee villages had palisades (reinforced walls) around them for protection.

Traditional Housing

Their homes were made using natural materials found in their environment. They were wooden frames covered with woven vines that had thatched roofs made with saplings plastered with mud.

These dwellings were just as strong and warm as the log cabins they were later replaced with.

Log Cabins

Later on, the Cherokee upgraded their mud huts to windowless log cabins, fitted with bark roofs, one single door, and a hole in the roof for smoke to escape.

On average, there would be about 30-60 cabins in a Cherokee town.

Farming

The Cherokees were traditionally hunter-gatherers who also farmed. The women harvested crops of corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers. They gathered berries, nuts and fruit to eat. They used wooden hoes for farming, and woven baskets for storing food.

The men were tasked with hunting.

Hunting

Cherokee men hunted deer, wild turkeys, and small game and fished in the rivers. They used bows and arrows or blowguns to shoot game, and spears and poles for fishing.

All of their tools, including weapons, were handmade.

Weaponry & Tools

Cherokee warriors fired arrows or fought with a melee weapon like a tomahawk or spear.

Other important tools included stone adzes (hand axes for woodworking), and flint knives for skinning animals.

Traditional Clothing

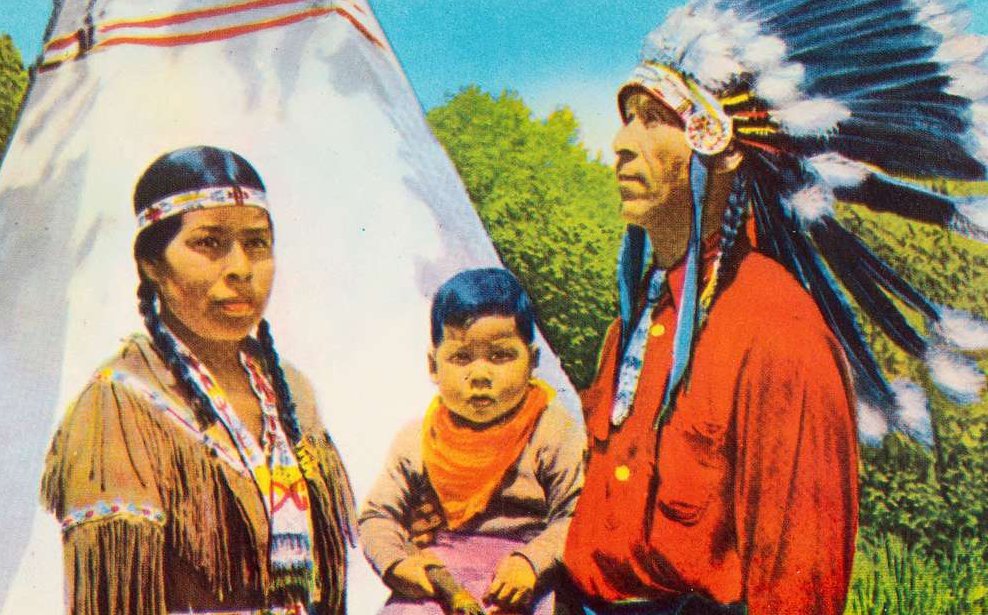

Traditional Cherokee men wore breechcloths and leggings. Cherokee women wore wraparound skirts and poncho-style blouses made out of woven fiber or deerskin.

They wore beautiful handmade moccasins on their feet.

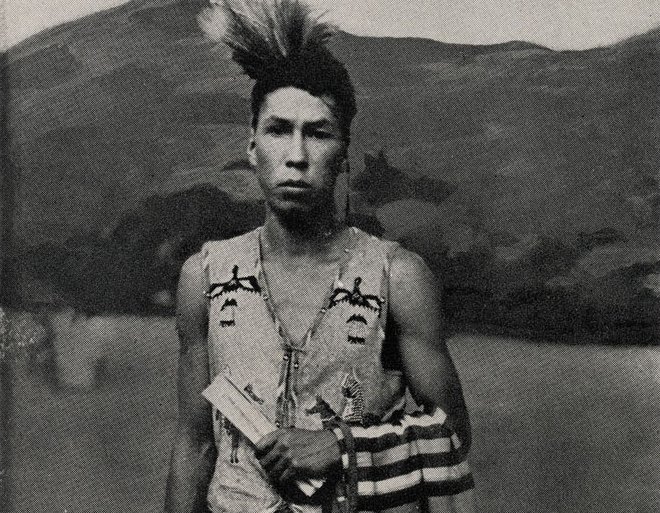

Salaamshots, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Salaamshots, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Clothing Adaptations

After colonization, Cherokee Indians adapted European costume into a characteristic style, including long braided or beaded jackets, cotton blouses and full skirts decorated with ribbon applique, feathered turbans, and the calico tear dress.

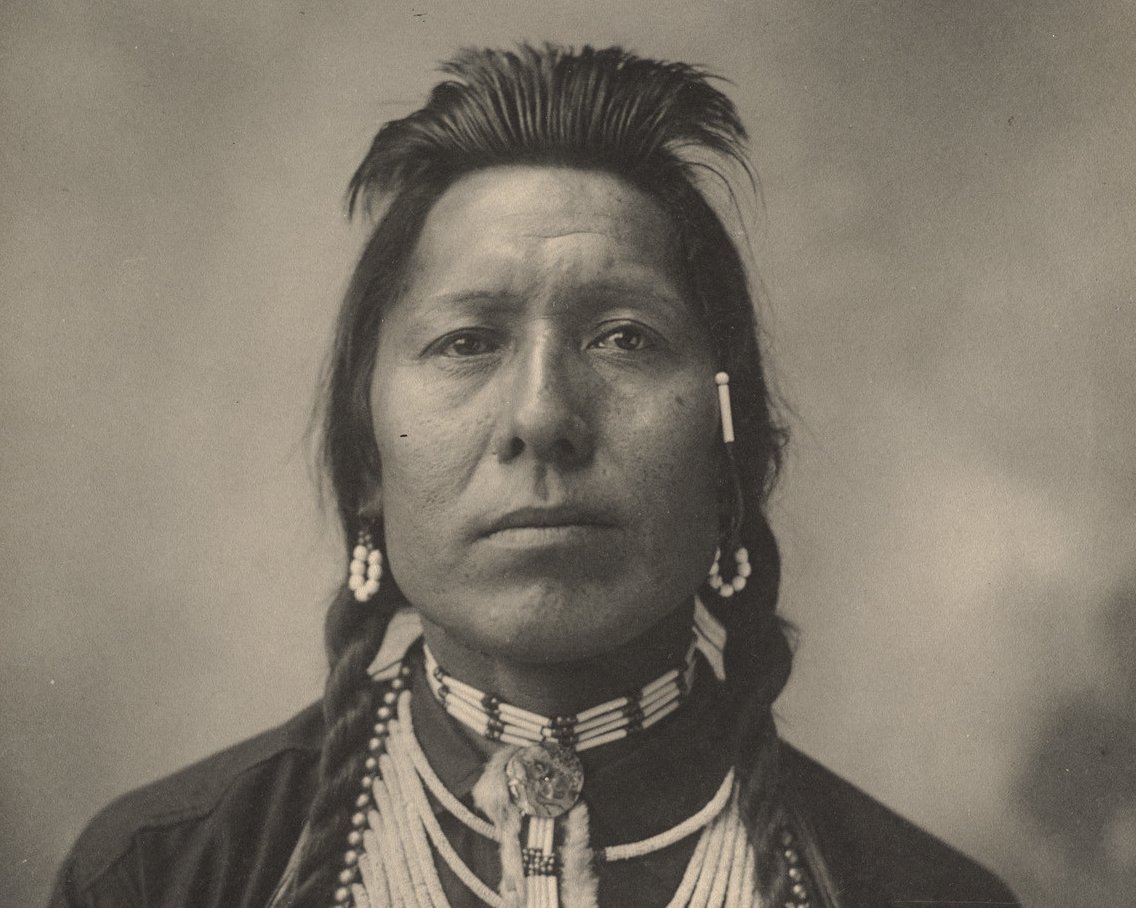

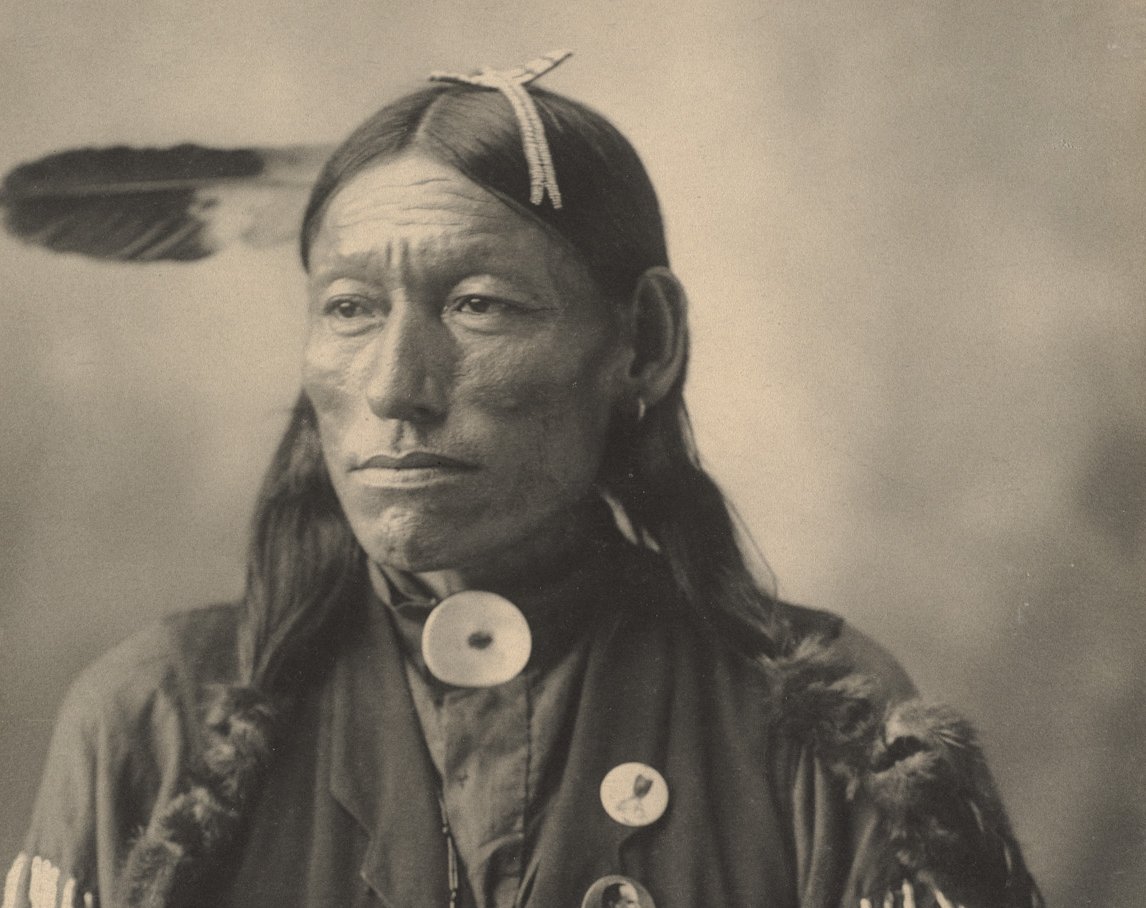

De Lancey Gill, Wikimedia Commons

De Lancey Gill, Wikimedia Commons

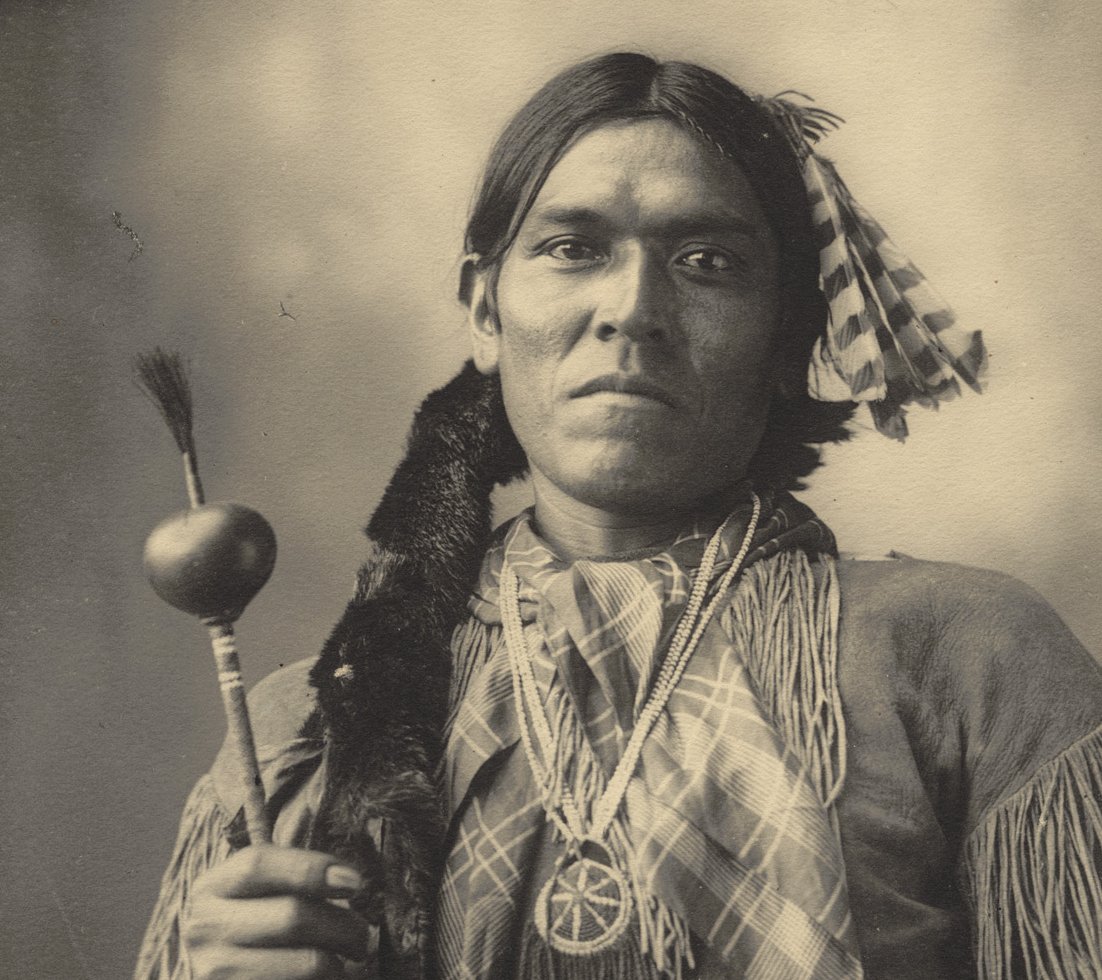

Traditional Styles: Men

Cherokee men usually shaved their heads except for a single scalplock. Sometimes they would also wear a porcupine roach.

They also decorated their faces and bodies with tribal tattoo art and also painted themselves bright colors in times of war.

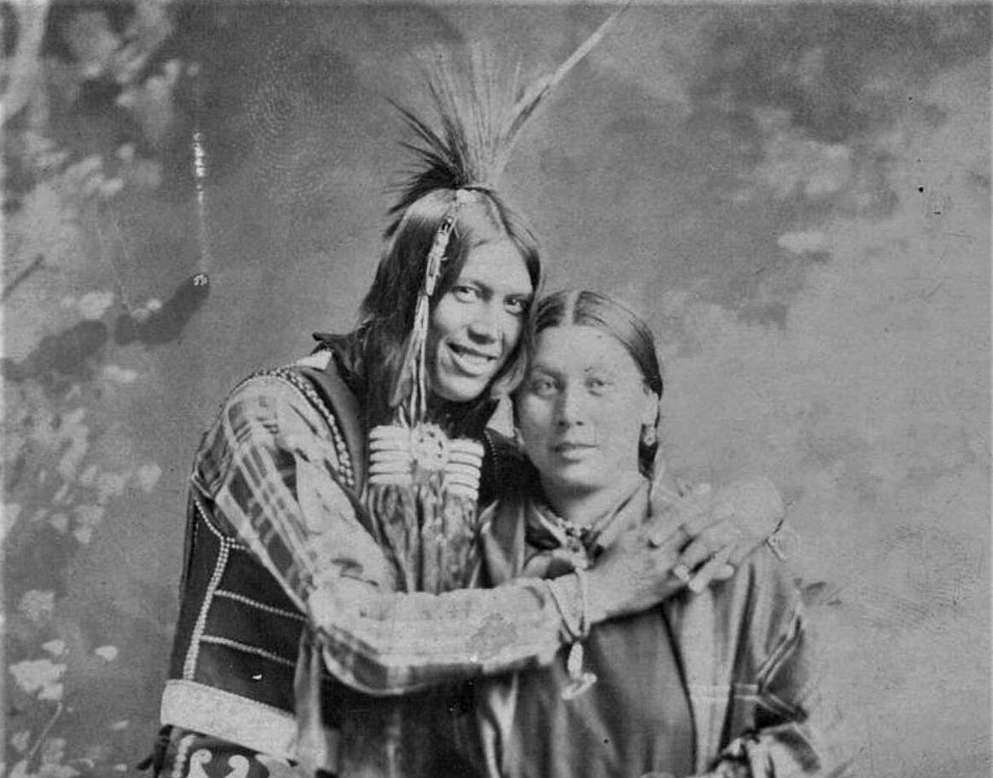

Traditional Styles: Women

Cherokee women always wore their hair long, cutting it only in mourning for a family member. They did not paint themselves or wear tattoos, but they often wore beaded necklaces and copper armbands.

Traditional Cherokee Identification

Traditional Cherokee Life and culture was similar to that of the Creek and other tribes of the Southeast.

Historically speaking, the Cherokee Nation was made up of two different types of towns: red and white, symbolizing war and peace respectively.

Peace and War

The chiefs of individual red towns answered to a supreme war chief, while the officials of white towns answered to a supreme peace chief. The peace towns provided sanctuary for wrongdoers; war ceremonies were conducted in red towns.

Gender Roles

The Cherokee had an even division of power between men and women.

Cherokee men were in charge of hunting, war, and diplomacy. They made the political decisions for the clan, and the chiefs were always men.

Gender Roles: Women

The Cherokee women were responsible for everything and anything to do with the home and family. They owned the land, built the homes, grew the gardens/gathered the food, cooked the meals, raised the children, made the tools, and gathered firewood.

They also made the social decisions for the clans.

The Council of Grandmothers

Aside from being homemakers, Cherokee women served their community in many important ways.

As a woman gained wisdom and experience, she could sit on various important councils. In the Cherokee tradition, a “Council of Grandmothers” would convene who had authority to nullify even the Chief’s decisions.

That’s not the only power Cherokee women had.

Medicine Women

Some of them became female shamans or medicine women in the tribes. It was often said that Cherokee women made better shamans than the men, as they had more “healing power.”

The Healing Power

Medicine women could heal ill souls using their chants and connections to the spirit world. They also incorporated herbs in their portfolio of medicines and healing techniques.

The Cherokee women are known for taking on more of a social role within their tribe, than a strictly biological one.

Children

When a Cherokee couple get married, the man became part of the woman’s clan, and their children belonged to the woman.

The women of the clan took care of all of the children together, so the children had many women they considered “mothers”—and the fathers were someone else entirely.

The Role of a Father

In traditional Cherokee culture, the biological father played a smaller role than you’d think. The most important male relative in a Cherokee child’s life was his mother’s brother, not his father.

In fact, the father was not formally related to his offspring.

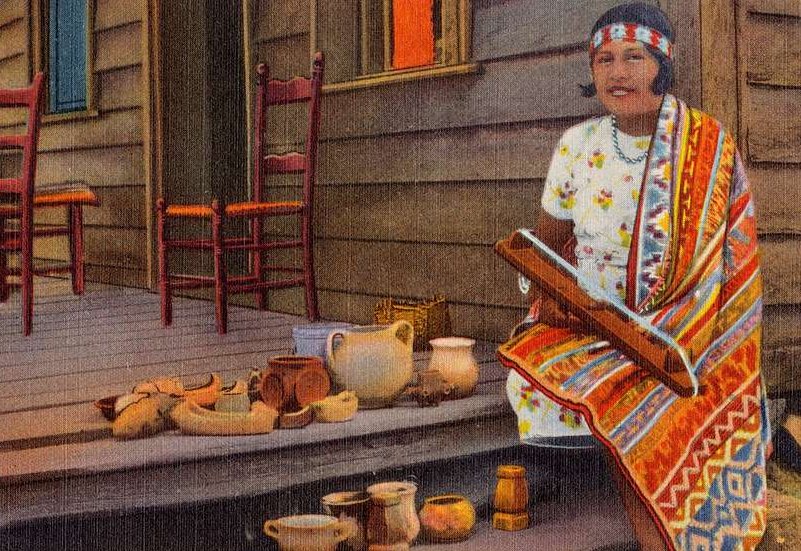

Sergei Bachlakov, Shutterstock

Sergei Bachlakov, Shutterstock

An Unorthodox Approach

According to Theda Perdue, a professor at the University of North Carolina and author of Cherokee Women: Gender and Culture Change, “white men who married Indian women were shocked to discover that the Cherokees did not consider them to be related to their children, and that mothers, not fathers, had control over children and property.”

And that’s not all that was confusing.

Marriage and Divorce

Since the Cherokee were a matrilineal society, the women had complete autonomy and were free to marry whomever they wanted, obtain divorce easily, and rarely experienced any sort of mistreatment from men.

This type of women-led society may sound refreshing to us now, but it was confusing for colonists back then who were taught to honor men before women.

Property Ownership

As mentioned before, Cherokee women were the property owners. They inherited their land from their mothers and provided a home for their extended families.

And, after colonists arrived, in order to keep white men from marrying Cherokee women for profit—they had a specific law in place in terms of divorce.

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

Protecting Their Land in a Divorce

Should a white man abandon his Cherokee wife without good reason, he forfeited Cherokee citizenship and paid a settlement determined by the Cherokee Committee and Council for breach of marriage.

This ensured that a Cherokee woman’s property remained in the right hands.

The Laws of Attraction

Speaking of divorce, it was not uncommon for a Cherokee married couple to separate as a result of a loss of attraction. And adultery was not seen as a grand-crime.

Both men and women were sexually liberated, and unions were typically based on mutual attraction. Once the attraction was gone, a couple would freely separate and pursue other people.

This was somewhat common after having several children together.

Cherokee Teens

As Cherokee children got older, they would integrate themselves into the traditional gender roles of their culture. The boys would join the men for hunting and fishing and the girls would help around the house.

Although they had more chores and less time to play, they did have dolls, toys, and games.

Marriage

Once a Cherokee boy reached the age of 17, he was expected to marry. Girls were able to marry at age 15. The boy had to seek consent from the girl’s entire clan, as well as his own parents.

The boy would also have to provide an offering of deer meat as a symbol of his ability to take care of her.

Once the clans approved of the union, the tribe’s priest would hold a marriage ceremony.

Marriage Rules

Men were only allowed to court one woman at a time. And while monogamous marriages were most common, polygamist marriages were allowed. Usually though, this was only the case when a man would marry his brother’s widow (or his wife’s cousin or niece) so someone would take care of her.

Losing Their Heritage

Over the years, the Cherokee lost many of their traditional ways of life as the Spanish, French and English all tried to colonize parts of the Southeast, including Cherokee territory.

The Cherokee were involved in numerous battles with other Indigenous tribes who were on opposing sides of various alliances.

A British Alliance

By the early 18th century, the Cherokee had chosen an alliance with the British in both trading and military. Despite breaking down on occasion, this alliance held strong for much of the 18th century.

Hervey Smyth, Wikimedia Commons

Hervey Smyth, Wikimedia Commons

Battles and Treaties

At this time, the Cherokee had fought in numerous wars and battles. At times, treaties were renegotiated and people who were once enemies became allies.

Cherokee Political Power

During the mid-1730s, political power among the Cherokee remained decentralized, and towns acted autonomously.

In 1735, the Cherokee were said to have 64 towns and villages, with an estimated fighting force of 6,000 men.

But that number quickly dipped.

A Smallpox Epidemic

As a result of further colonization, in 1738 and 1739, a smallpox epidemic broke out among the Cherokee, who had no natural immunity to the new infectious disease.

Nearly half their population died within a year—and those who didn’t pass from the disease took matters into their own hands.

A Tragic Result

Many Cherokee people who did not ultimately die as a result of the disease ended up permanently disfigured and remained constantly unwell.

As a result, hundreds of them ended up taking their own lives.

The Cherokee War

Even after being struck by an unimaginable loss, life for the Cherokee had to go on—which included the seemingly never-ending battles that comprised both the French and Indian War and the Cherokee War.

Henry Timberlake, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Timberlake, Wikimedia Commons

The French and Indian War

During the French and Indian War (1754–1763) the Cherokee remained allies with the British, while the French had allied themselves with several Iroquoian tribes, which were the Cherokee’s traditional enemies.

However, eventually this alliance broke.

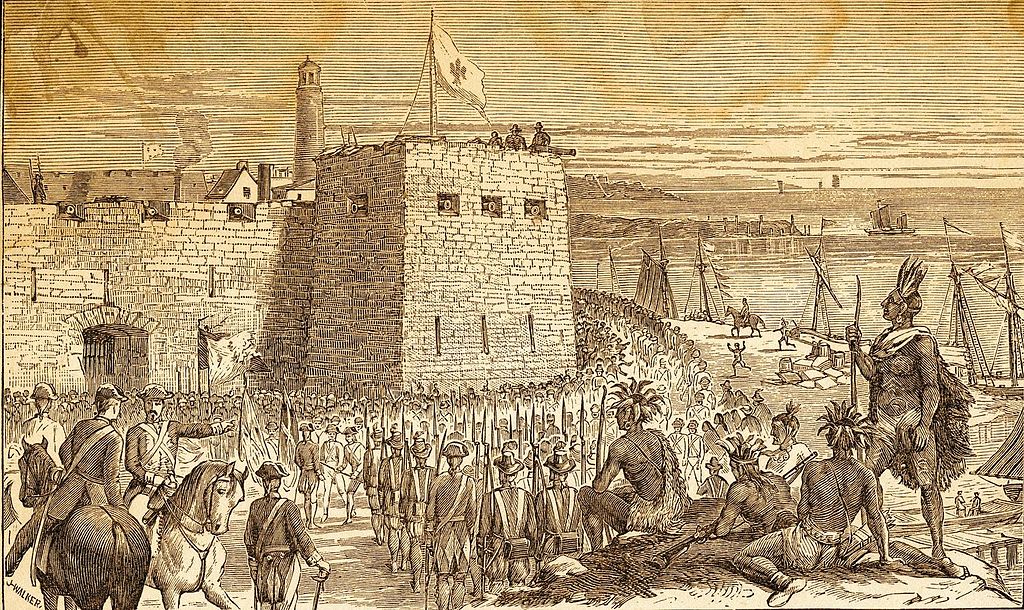

John Henry Walker, Wikimedia Commons

John Henry Walker, Wikimedia Commons

Sudden Destruction

By 1759 the British had begun to engage in a “scorched-earth policy” that led to the destruction of native towns, including those of the Cherokee and other British-allied tribes.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Broken Alliances

The Cherokee found themselves breaking old alliances and creating new ones with other native tribes they were once against in battle—marking the beginning of the Cherokee War.

The Cherokee War

The Cherokees retaliated in North Carolina in spring 1759, and the conflict spread southward. Cherokee women and children were being brutally attacked with numerous incidents being so heinous they would now be considered war crimes.

Cherokee warriors avenged their deaths—but not without further consequence.

A Treaty Without Peace

Several Cherokee headmen and their companions were taken hostage by the U.S. governor’s team of nearly 1,300 men.

A treaty was then negotiated—but not the kind of treaty you’d expect.

Calling for Surrender

In December of 1759, a treaty was signed which provided for Cherokee headmen to be kept hostage until several known Cherokee assassins were surrendered.

The treaty did not secure peace. Only a few short months later, things escalated.

The Ambush

In February of 1760, a Cherokee leader—who both signed the treaty and was a hostage—set an ambush for the commander of the European fort that had the remaining hostages.

The Cherokee lured the commander from his fort, successfully taking his life—but not without collateral damage.

Revenge

After the unexpected death of their commander, the remaining military men inside the fort executed the rest of the Cherokee hostages in revenge.

British troops were then called in to assist in the war effort.

A Presumed Victory

By mid-spring, 1,600 British solders marched into South Carolina to defeat the Cherokees. After burning their existence to the ground, they thought they had reached victory—but they were wrong.

A Strategic Move

Cherokee tribes in the upper towns continued their fight, even after losing so many.

In August of that year, the Cherokee offered the garrison safe passage to Fort Prince George—but unbeknownst to the Europeans, it was a ploy.

Chris Light, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Chris Light, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sneak Attack

Once the troops were outside the fort, the Cherokees attacked, killing its commander, and twenty-three others (the number of Cherokee hostages who lost their lives at Fort Prince George), and they took many captives.

While this may sound victorious, it was once again, not without further consequence for the Cherokee.

The Final Expedition

The following summer, the U.S. military led an expedition of more than 2,400 troops to subdue the middle and upper towns.

They defeated Cherokee forces and systematically destroys over 15 towns and 15,000 acres of crops. This ultimately broke the Cherokee’s power to wage war.

Official Defeat

By July of 1761, the Cherokee were officially defeated and signed a treaty that had both parties agreeing to exchange captives.

In addition, a dividing line was established that separated the Cherokees from South Carolina lands—significantly reducing Cherokee hunting grounds.

Post-War Population

After the war, the Cherokee population had been reduced to a total of 6,900 people—with 2,300 being warriors.

Worst of all, this was still not the end for the Cherokee.

Land Surrender

The Cherokee remained in a constant fight for land and in 1773, another treaty had the both the Cherokee and the Creek surrendering more than two million acres of tribal land in Georgia to relieve a portion of their “debt” to European traders.

Forced Colonization

Only two years after this, more land was surrendered in Kentucky and a final attempt at revenge left the Cherokee retreating in disgrace.

Colonization was inevitable.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Surrender

The Cherokee could only achieve peace by surrendering. They gave up vast tracts of territory after reluctantly signing two more treaties that were not in their favor.

Peaceful Cherokee people remained in the area until the 1830s, when the U.S. government then forced them to move to Oklahoma under the Indian Removal Act.

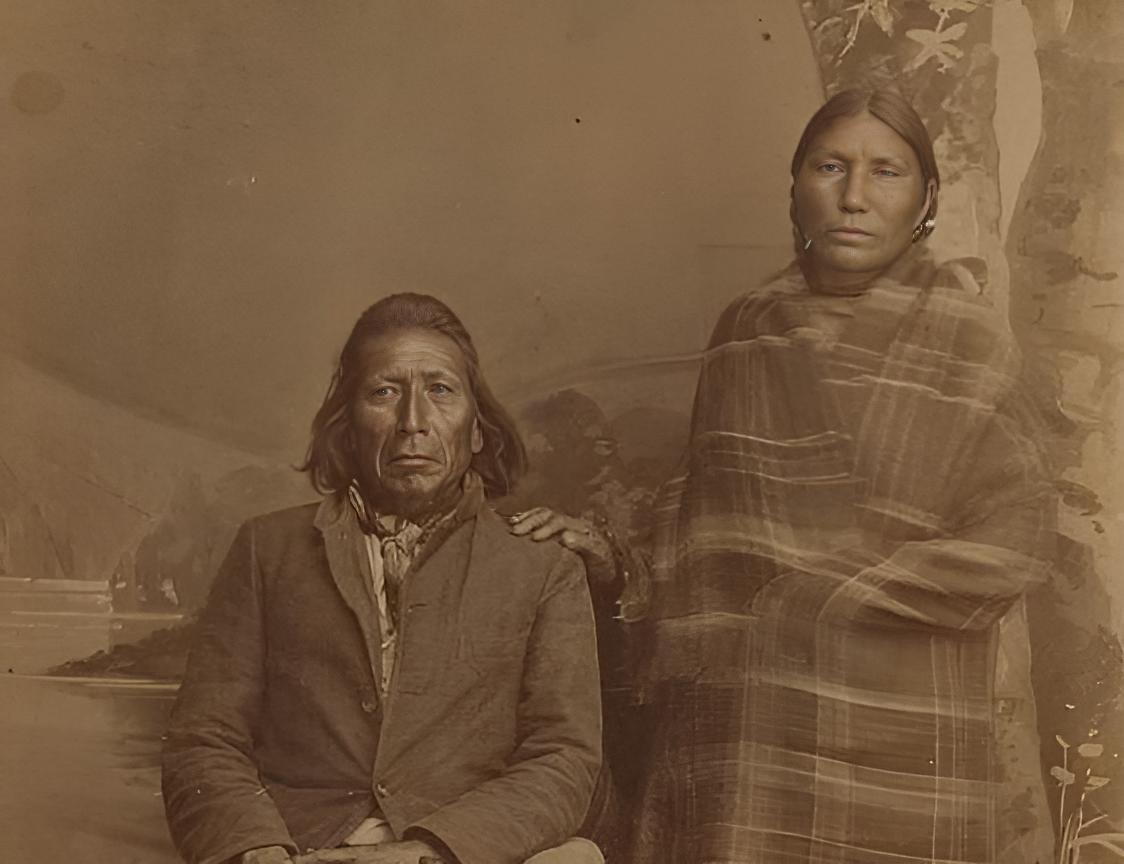

American Culture

The Cherokee were then assimilated into American settler culture, and even formed a government similar to that of the United States, where they continued to fight against settlers for their land for many more years.

At the same time, they adopted colonial models of farming, weaving, and home building.

The Syllabary

One of the most remarkable additions to their culture was their syllabary—a set of written symbols used to represent the syllables of the words of a language.

In 1821, a Cherokee named Sequoyah who had served in the U.S. Army developed the syllabary of the Cherokee language.

Syllabary Success

The syllabary was so successful that, within a short time almost the entire tribe had become literate.

A written constitution was adopted, and religious literature thrived, including translations from the Christian Scriptures.

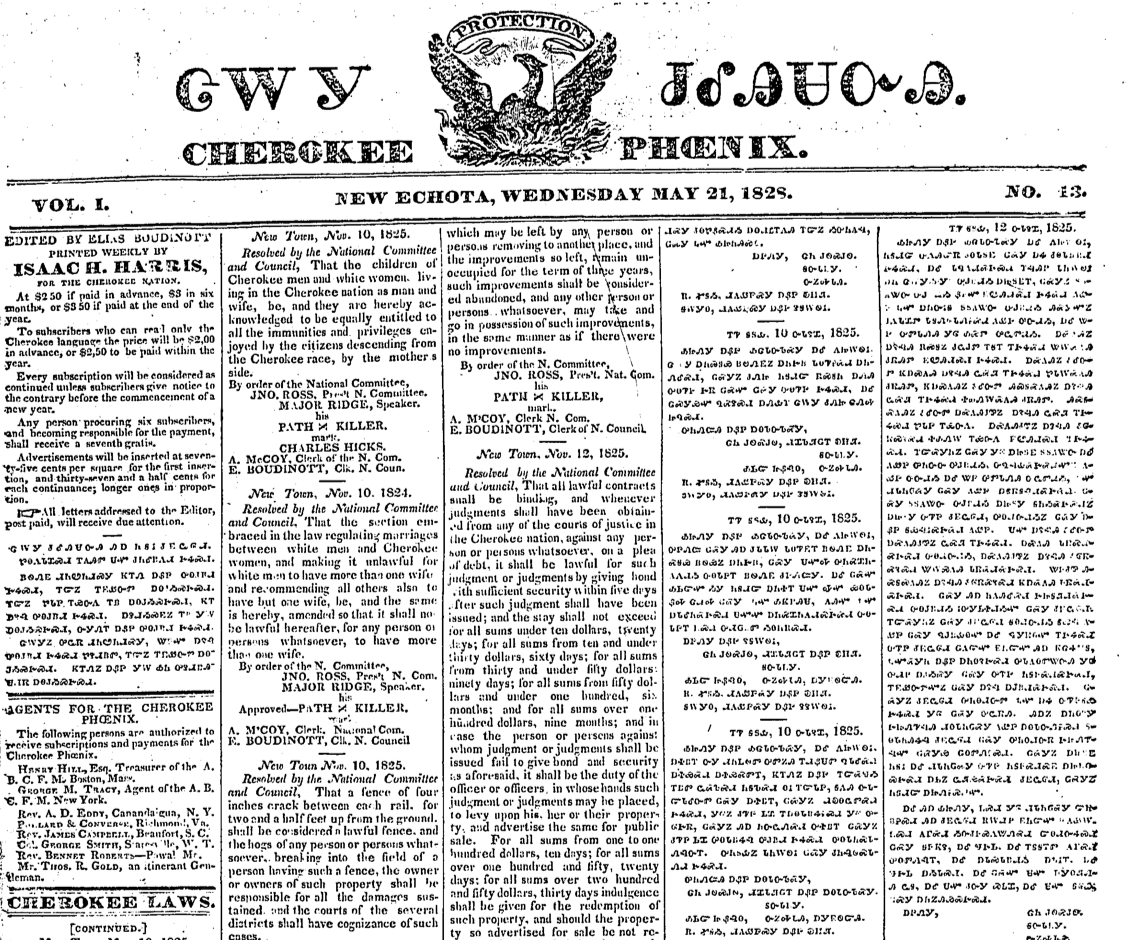

The Cherokee Newspaper

In February of 1828, Native Americans’ first newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, began publication.

The Cherokee’s quick entry into settler culture may have seemed promising, but it was not enough to protect them from their land hungry enemies.

Cherokee Phoenix, Wikimedia Commons

Cherokee Phoenix, Wikimedia Commons

The Treaty of Echota

When gold was discovered on Cherokee land in Georgia, the government immediately called for action, creating the Treaty of Echota—which a small minority of Cherokee signed.

The treaty basically sold all Cherokee land east of the Mississppi River to the U.S. government for $5 million.

Rejection

The Cherokee people rejected the treaty and took their case to the Supreme Court where ultimately the judge sided with the tribe and declared that Georgia had no claim to their land.

But Georgia officials ignored the court’s decision—and took matters into their own hands.

The Indian Removal Act

In 1830, the Indian Removal Act had U.S. military officials forcefully remove thousands of Cherokee people from their homes at gunpoint.

Over 16,000 ended up in horrific camps while their homes were being burned to the ground.

It'sOnlyMakeBelieve, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

It'sOnlyMakeBelieve, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

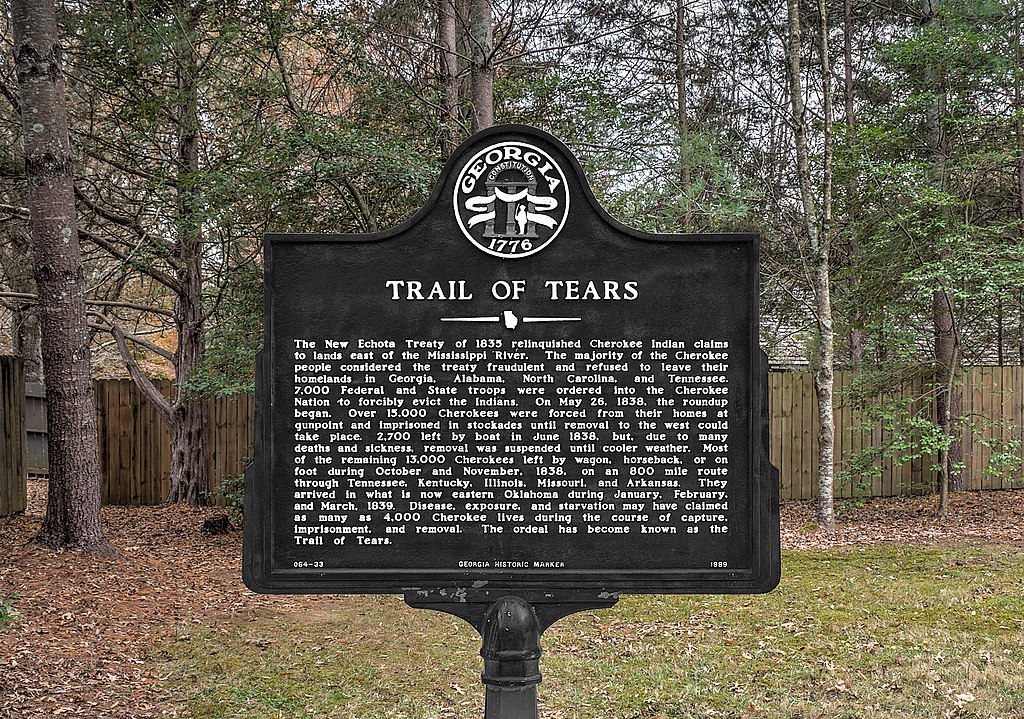

The Trail of Tears

By the late 1830s, the Cherokee refugees—those who were still alive—were forced to march, on foot, in groups of around 1,000 to a new location. This march is known as the Trail of Tears.

This forced relocation also included other nations, such as the Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole.

Casualties

Over 100,000 Indigenous peoples were forced to march, and over 15,000 lost their lives along the way from starvation, dehydration, illness, and harm.

The term Trail of Tears invokes the collective suffering they experienced during the horrifying ordeal.

Slavery

During the Trail of Tears, many Cherokee were taken away as slaves, especially women and children.

Slavery was a component of Cherokee society prior to European colonization, as they often took slaves themselves during conflicts with other tribes, and became slaves of rival tribes.

Oklahoma

Those who made it to the end of the Trail of Tears alive ended up in reservations in Oklahoma, where further controversies ensued with settlers who were already there—including other Native tribes.

Their new settlement was not any easier for them to navigate, and their battles continued.

Sharon Baker, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sharon Baker, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Retribution

On their new reserve, the Cherokee were at odds with other tribes and reprisal was made on those who had signed the Treaty of Echota—which led to their forced removal of their homelands.

Feuds were brutal and more Cherokee lives were lost.

Joining Forces

Cherokee settlers eventually joined four other tribes—the Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole—all of which had been forcible removed from the Southeast in the 1830s.

And for the next 75 years, each tribe had a land allotment and quasi-autonomous government similar to that of the United States.

Dissolving Cherokee Nation

During 1898–1906 the federal government dissolved the former Cherokee Nation band, and any other tribal governments, to make way for the incorporation of Indian Territory into the new state of Oklahoma.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Oklahoma Statehood

When Oklahoma became an official state in 1907, some of the land was given to individual tribe members, and the rest was opened up to homesteaders, held in trust by the federal government, or given to freed slaves.

Doug Floyd, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Doug Floyd, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Reinstatement of Cherokee Nation

From 1906 to 1975, the structure and function of the tribal government were completely obsolete.

But in 1975, the tribe drafted a constitution that became officially valid the following summer—finally giving federal recognition to Cherokee Nation.

A Name Change

In 1999, the Cherokee Nation added several provisions to its constitution, which included changing the designation of the tribe to just “Cherokee Nation,” instead of “Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma,”—gaining even more independence.

Three Recognized Tribes Today

Today, there are three federally recognized Cherokee bands in the United States: Cherokee Nation, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians.

Cherokee Nation being the largest of the three.

Mersede Mirshamsi, Shutterstock

Mersede Mirshamsi, Shutterstock

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

Today, the Qualla Boundary reservation in North Carolina is home to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and has a population of over 8,000 Cherokee—primarily direct descendants of Indians who managed to avoid or escape the Trail of Tears.

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians

The UKB gained federal recognition in 1946. Enrollment in the tribe is limited to people with a quarter or more of Cherokee blood. Many members of the UKB are descended from Old Settlers—Cherokees who moved to Arkansas and Indian Territory before the Trail of Tears.

Prospering Communities

Each of these Cherokee bands have expanded economically, providing equality and prosperity for their citizens.

With significant and successful businesses, newly constructed health clinics, schools, roads, bridges, and educational community programs, they’ve become a powerful and positive force in America.

Current Population

In 2015, the Cherokee Nation, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians, and the Eastern Band of Cherokees had a combined enrolled population of roughly 344,700.

Today, that number is estimated at over 450,000.

Cherokee Members

While there are over 200 groups claiming to be Cherokee nations, tribes, or bands—the three federally recognized groups note that they are the only groups who have the legal right to present themselves as Cherokee Indian Tribes.

A Powerful Come Back

The Cherokee Indians spent many years defending their land, losing hundreds of battles and countless lives. After ultimately surrendering and losing everything they had, they have slowly built their lives back, gaining more power than ever before.

Cherokee Nation Today

Today, Cherokee Nation is one of the largest employers in northeast Oklahoma and is the largest tribal nation in the country.

As the governing body of the Cherokee people, the Cherokee Nation has the right to structure its own government and constitution; make and enforce its own laws; regulate business, land, environment, and wildlife; and impose taxes within the Cherokee Nation’s jurisdiction.

Kim Kelley-Wagner, Shutterstock

Kim Kelley-Wagner, Shutterstock