Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

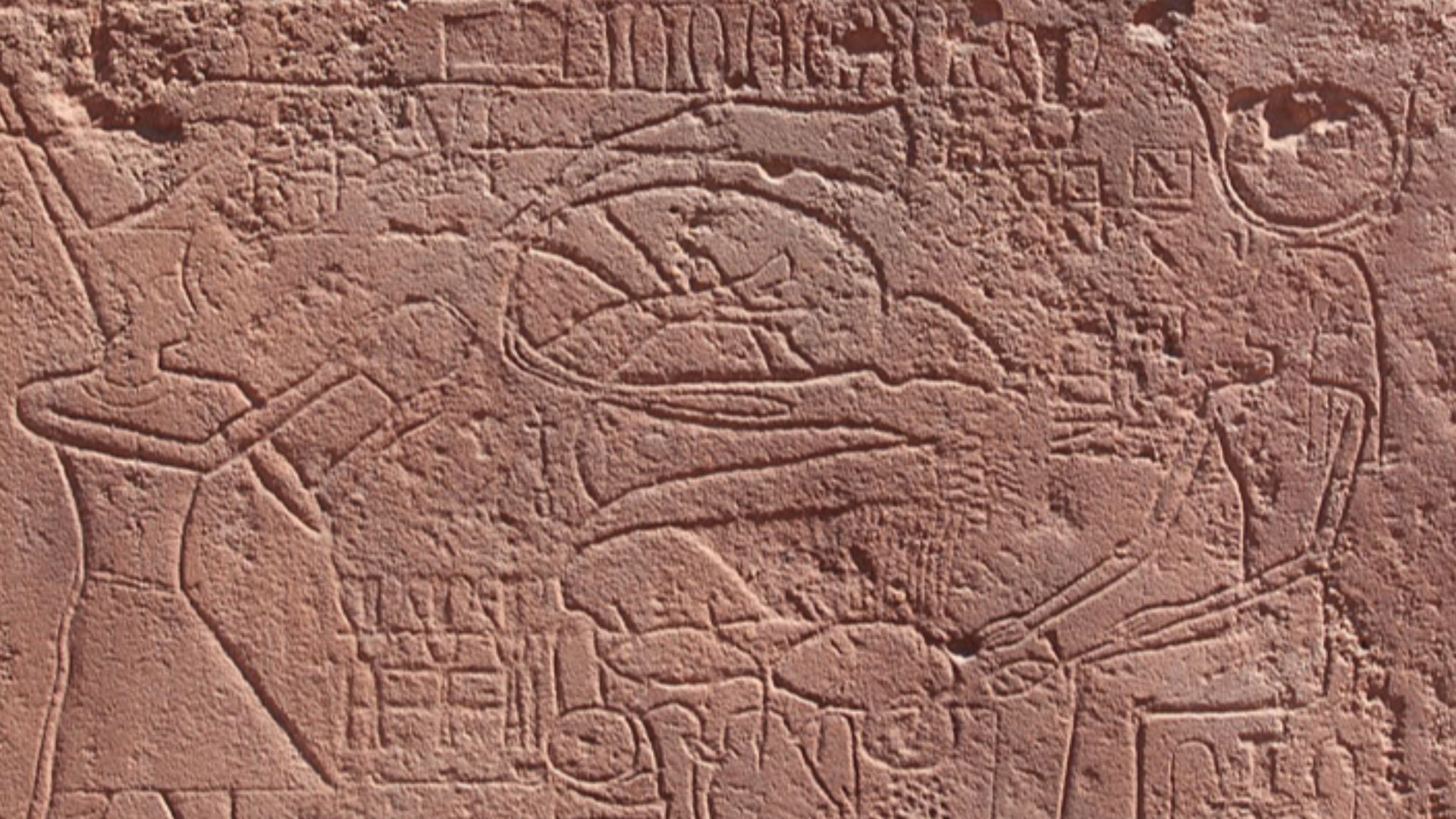

It began more than a century ago, deep within the ancient turquoise mines of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. There, hidden among the rugged cliffs and wind-carved passageways, faint carvings etched into the stone puzzled archaeologists for decades—symbols that seemed familiar, yet resisted any confident translation. Early explorers copied them frantically into notebooks, hoping someone in the future would decode the strange marks. What they didn’t know was that these carvings would one day become the center of a debate stretching across archaeology and biblical scholarship. Then came a new interpretation, one that suggested a link no one had dared imagine. What those markings revealed would challenge long-held assumptions and change how we understand the origins of writing itself.

A Forgotten Script Reveals A Familiar Name

The inscriptions were first unearthed in the early 1900s at Serabit el-Khadim, a windswept desert site known both for its turquoise deposits and for its temple dedicated to Hathor, who is the Egyptian goddess often associated with mining and protection. The workers who came here—many of them foreigners brought from Canaan and surrounding regions—left behind crude symbols carved into the rock near shafts and work camps. For decades, early archaeologists believed these carvings were nothing more than simple workers’ notes written in an early Semitic script, perhaps a primitive recordkeeping tool or a rough attempt at communication by laborers not trained as scribes. Their shapes appeared too irregular, too experimental to resemble the polished hieroglyphs and hieratic writing used by Egypt’s literate elite.

However, that recently changed when epigraphers reexamined the symbols using modern linguistic analysis and an expanded understanding of proto-alphabetic systems. What they uncovered was remarkable: one inscription may contain a sequence of letters resembling a name many people instantly recognize—“Moses.” This possibility immediately drew attention, since the site dates back nearly 3,800 years, roughly aligning with the broad period some traditions associated with the early Hebrew presence in Egypt. While the historical Moses remains a subject of debate, the timing alone made scholars take notice.

If this discovery really holds up in truth, it suggests that the language carved into those mine walls represents one of the earliest steps toward the alphabetic scripts that shaped later Semitic writing traditions we know. It implies that ordinary workers, people outside the elite society in royal courts and priestly circles, also played significant roles in developing the world’s first alphabetic ideas. That connection also sheds new light on Egypt’s ancient labor communities. And learning that in this day and age feels surprisingly refreshing and genuinely exciting. The writing we do today started somewhere.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

The Debate Among Historians

As the translation gained traction, scholars began to divide. Some embraced the reinterpretation as an exciting clue about early script development and the fluid movement of ideas through Egyptian labor networks. To them, the potential appearance of a name like Moses is less about confirming a single historical figure and more about seeing evidence of shared linguistic roots and interactions between Egyptian authorities and Semitic-speaking workers. Others urged caution. They point out that ancient names often sound similar across multiple languages, and that coincidences in phonetics are not uncommon. In addition, names found in early inscriptions do not necessarily refer to the same individuals described in later religious texts—a distinction crucial for separating mythology from archaeology.

Still, the idea resonated widely because it offers a rare intersection between material evidence and long-standing narratives. Think of it like a small window into how stories form around real places and real people, regardless of the era. The discovery encourages conversations about how memory and religion are intertwined in early civilizations. And even if the link to Moses remains unproven, the inscriptions themselves shed light on how workers from distant lands communicated and recorded their presence inside Egypt’s mining system. The same way you tap a message into your phone, they carved theirs into stone, leaving a record of who they were and why they were there.

What This Means For Understanding The Past

Beyond the debate, the discovery has revived public interest in the origins of alphabetic writing. The Sinai inscriptions may represent one of the earliest steps toward a written communication system that ordinary people, not just scribes or priests, could use. That shift transformed how stories and traditions were passed across generations. Whether the name on the stone truly connects to Moses or simply mirrors a common term of the time, it reminds us how a few carvings in a remote desert cave can still stir the world’s imagination. The past, it seems, continues to whisper new versions of stories we thought we already knew.

Einsamer Schutze, Wikimedia Commons

Einsamer Schutze, Wikimedia Commons