The Marvel That Just Got More Interesting

Stonehenge always seemed mysterious enough on its own, but a discovery around the site added an unexpected layer. The ground reveals something huge, and the monument starts to look like only one piece of a much larger plan.

The Mystery Of Stonehenge

For centuries, this prehistoric monument has sparked curiosity because no written records explain why it was built. Its unusual design and remote age make it one of humanity’s most enduring puzzles, which invites endless theories about the people who created it and the purpose it once served.

Where Is Stonehenge?

It stands on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, a broad, open stretch of grassland in southern England. This landscape is dotted with prehistoric earthworks and burial mounds, which makes the area one of Europe’s richest archaeological zones and an ideal setting for ceremonial activity.

Simon Burchell, Wikimedia Commons

Simon Burchell, Wikimedia Commons

What Does Stonehenge Look Like?

The monument features massive upright stones arranged in circles and horseshoe shapes, connected by horizontal lintels balanced on top. Some stones reach over 20 feet high. Even in its partly ruined state, the structure shows remarkable symmetry and a layout planned with clear intention.

When Was It Built?

Construction unfolded over many centuries. The earliest earthworks appeared around 3000 BCE, followed by the arrival of smaller bluestones. The larger sarsen stones were set into place around 2500 BCE. Later generations made further adjustments. The monument evolved as beliefs and traditions changed.

Peter Trimming, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Trimming, Wikimedia Commons

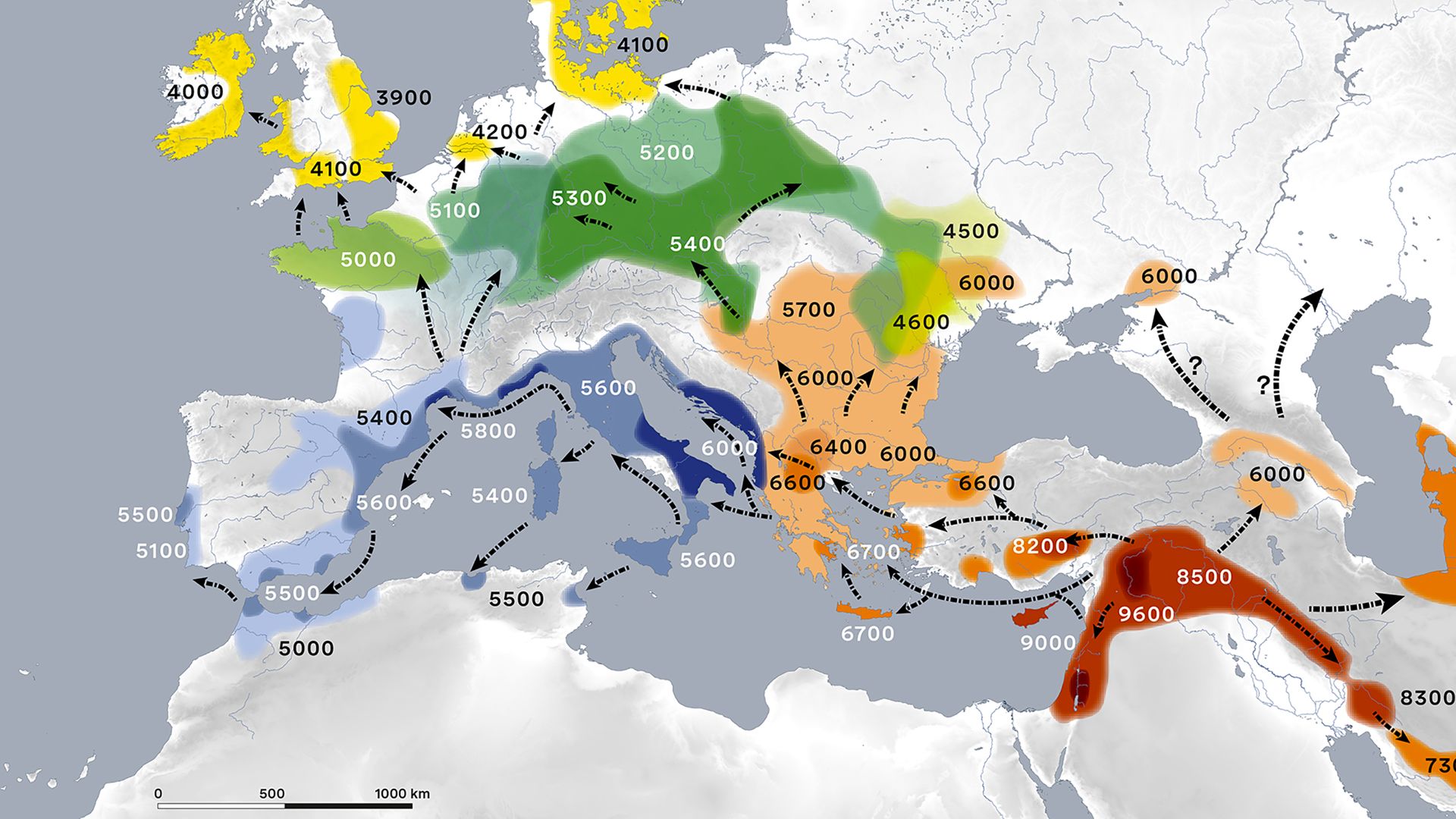

Who Built Stonehenge?

Farming communities of the Neolithic period raised this monument long before metal tools or wheels existed. Their society relied on cooperation and strong leadership. Building such a large structure required skills passed down through generations in an organized and tightly connected culture.

Detlef Gronenborn, Barbara Horejs, Börner, Ober, Wikimedia Commons

Detlef Gronenborn, Barbara Horejs, Börner, Ober, Wikimedia Commons

Tools & Techniques

Without metal tools or wheels, builders used wooden sledges and rope made from plant fibers to move enormous stones. They dug deep pits with antler picks, raised stones using timber frames, and relied on teamwork to achieve engineering tasks few imagined possible for the time.

Brian Deegan , Wikimedia Commons

Brian Deegan , Wikimedia Commons

Where Did The Stones Come From?

The larger sarsen stones likely came from Marlborough Downs, about 20 miles away. The smaller bluestones traveled much farther—over 140 miles from the Preseli Hills in Wales. Transporting them suggests long-distance connections among communities spread across different regions.

Brian Robert Marshall, Wikimedia Commons

Brian Robert Marshall, Wikimedia Commons

Why Was It Important To Them?

For early farming societies, monuments marked identity as well as a sense of belonging. Such places may have hosted ceremonies tied to seasons or ancestors. Building something so large created unity and expressed beliefs that shaped community life for generations.

Peter Trimming, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Trimming, Wikimedia Commons

Stonehenge As A Calendar

The monument aligns with the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset to signal that people tracked key moments in the solar year. These alignments helped communities predict seasons, guide farming cycles, and coordinate gatherings—turning the site into a practical and symbolic marker of time.

Solipsist~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Solipsist~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Stonehenge As A Temple

Many researchers believe it was designed as a ceremonial center. Its impressive layout and controlled entrances suggest rituals took place here, possibly honoring deities or natural forces that the people believed in. The monument’s scale shows people intended it to be a place of deep spiritual meaning.

Stonehenge As A Burial Ground

Excavations have revealed cremated human remains buried in and around the site’s earliest features. Many belonged to people of high status, which suggests this landscape once served as a prestigious cemetery. These burials hint at a place tied to honoring influential members of early society.

Adamsan (talk) (Uploads), Wikimedia Commons

Adamsan (talk) (Uploads), Wikimedia Commons

Stonehenge As A Healing Center

Some researchers propose that the monument attracted people seeking cures. The bluestones, moved from Wales, were believed by some ancient cultures to hold special properties. Evidence of individuals with injuries or illnesses buried nearby supports the idea of pilgrimage connected to wellness.

Ryan Bodenstein, Wikimedia Commons

Ryan Bodenstein, Wikimedia Commons

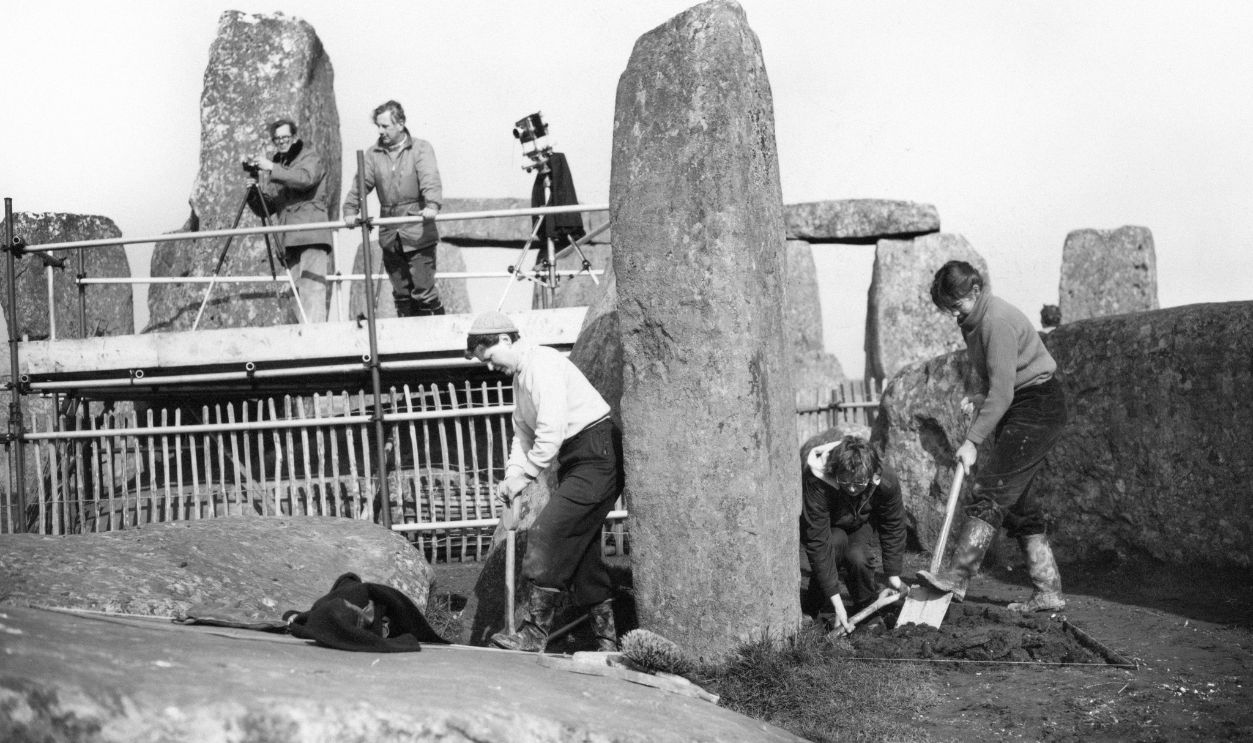

Early Excavations

Between the 1600s and 1800s, antiquarians explored the site using rudimentary methods, sometimes causing more damage than insight. Still, their notes and sketches marked the first attempts to interpret the monument to lay the groundwork for more scientific investigations later.

Rijksmuseum, Wikimedia Commons

Rijksmuseum, Wikimedia Commons

Modern Archaeology Tools

Today’s researchers use ground-penetrating radar, LiDAR mapping, precise carbon dating, and DNA analysis to examine the area without disturbing it. These technologies reveal buried features and even population movements. This turns the area into one of the best-studied prehistoric sites in the world.

The Charles Machine Works, Wikimedia Commons

The Charles Machine Works, Wikimedia Commons

The Wider Area

The monument is only one part of a larger ceremonial network. Nearby sites like Durrington Walls, the Avenue, and Woodhenge reveal an area built for gathering and processions. Together, they show this region functioned as a major social and ritual hub.

David Gearing , Wikimedia Commons

David Gearing , Wikimedia Commons

Artifacts & Human Remains

Excavations across the area uncovered pottery, animal bones, stone tools, and cremated burials. These finds reveal the lifestyle that the people had in those days. Together, they help archaeologists piece together the daily traditions surrounding the monument and the possible use of building it.

Breakthrough Moment

A major turning point came when researchers detected enormous underground voids arranged in a wide circle far beyond the stone monument. Further study revealed they were ancient pits—so large and evenly spaced that they hinted at a monumental feature previously unknown to archaeology.

John Atherton, Wikimedia Commons

John Atherton, Wikimedia Commons

Sacred Boundary Evidence

The pits form a ring nearly 1.2 miles wide, each about 30 feet across. Their size and precise placement suggest they weren’t random holes but a deliberate boundary enclosing the entire ceremonial landscape. This large-scale design indicates the area held extraordinary significance for ancient communities.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

What It Means

The pit circle shows the stones were only one piece of a far larger spiritual complex. Instead of a single monument, the entire area was shaped for ceremonies and observance. It proves early societies planned on a geographic scale far bigger than previously believed.

Michael Graham, Wikimedia Commons

Michael Graham, Wikimedia Commons

Ceremonial Gathering Place

The new discovery supports the idea that people traveled from long distances to gather here for seasonal events. The vast boundary suggests this area hosted major communal celebrations—moments of unity that strengthened alliances and shared identities across regions.

Rewriting Archaeology

The newly uncovered pit circle forces archaeologists to rethink how advanced Neolithic societies really were. Its scale suggests they understood surveying and coordination on a community-wide level. It challenges earlier assumptions that these groups only built small, local monuments with limited organization.

Connections To Other Sites

The discovery strengthens links between this landscape and other major prehistoric centers like Avebury, Newgrange, and the Orkney monuments. These places also used circles and ceremonial pathways. Together, they point to shared ideas spreading across ancient Britain and Ireland about ritual spaces and cosmology.

Astronomy Meets Ritual

The site’s alignments with the sun, combined with the vast pit boundary, suggest ceremonies may have coincided with key solar events. People likely gathered during solstices or seasonal transitions to merge sky-watching with ritual performances that marked time and guided agricultural cycles.

by simonwakefield, Wikimedia Commons

by simonwakefield, Wikimedia Commons

Social Glue

A project of this size required cooperation between distant communities. Gathering to dig pits, raise stones, and celebrate festivals may have helped forge alliances and reduce conflict. The site likely acted as a meeting ground where different groups strengthened their identity.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Tourism & Global Fascination

Today, millions visit the site each year, drawn by its age and unanswered questions. It inspires travelers to watch a marvel that still depicts their story. Its presence in documentaries and classrooms shows how this ancient monument continues to capture people from all around the world.

Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., Wikimedia Commons