"'This is why alchemy exists,' the boy said. 'So that everyone will search for his treasure, find it, and then want to be better than he was in his former life. Lead will play its role until the world has no further need for lead; and then lead will have to turn itself into gold. That's what alchemists do. They show that, when we strive to become better than we are, everything around us becomes better, too.'" —Paul Coelho, The Alchemist

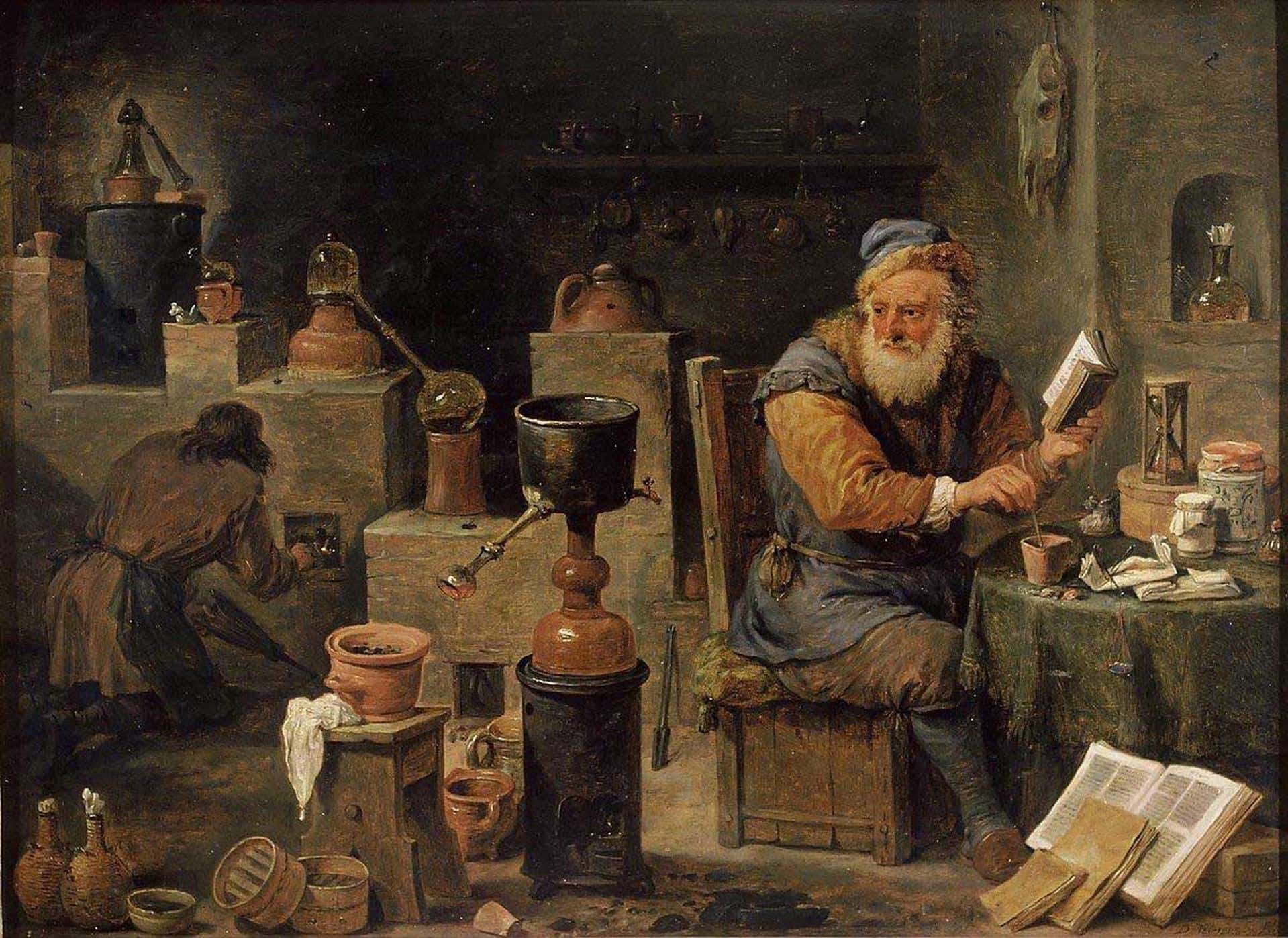

Alchemy isn’t just a fictional subject taught at Harry Potter’s Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry: In Europe and beyond it was a serious practice, combining scientific methods, philosophy, and occult spiritualism. Alchemists really believed they could gain transformative power over the elements of nature, and they dedicated their lives to the pursuit. Here are 41 facts to shed some light on the shadowy world of alchemy.

1. All That Glitters

One of the main goals of alchemy was to create the philosopher’s stone, an element that could turn base metals into gold. While the feat was never actually accomplished (or those coins under the couch cushions would be looking pretty good right now), real discoveries about the properties of metals were made along the way—meaning that alchemy has been considered a precursor to modern sciences like chemistry and mineralogy.

2. Forever Young

In addition to seeking endless wealth, some alchemists pursued the secret of perfect health: they believed that the philosopher’s stone could also bestow immortality. What’s the point of infinite riches if you don’t have the youth and health to enjoy them, right?

3. Chryso-whatnow?

The term “chrysopoeia” (pronounced KRIS-oh-PEE-ah) is from the Greek khrusos, “gold,” and poiein, “to make,” and refers specifically to the alchemical process of turning something into gold. I guess that makes Rumplestiltskin a…chrysopoeiac?

4. Where Did You Come From, Where Did You Go?

Europe was a little late to the alchemy game, since the pursuit didn’t make its way to the continent until the 12th century—before that, it had been practiced, albeit in different forms, in ancient Egypt, India, China, and the Islamic world long before.

5. Newtonian Laws of Alchemy

It turns out that Sir Isaac Newton, the guy who discovered, you know, gravity, was also a closet alchemist. It’s now theorized that science was just a hobby for Newton, and that his true passion was occult studies, particularly alchemy.

6. Improving Your Vocabulary

In the beginning, European alchemists had to rely primarily on translations of ancient Greek and Arabic texts for their information and alchemical recipes. This created an influx of new words into European languages: words like “booze” and “elixir” came from these texts.

7. Elementary, My Dear Watson

Medieval alchemy was rooted in Greek philosophy, which adhered to the belief that all things in existence were made up of a combination of the four natural elements: earth, air, fire, and water. (It was only in the early 1990s that heart was added to make up the full complement of the Planeteers.)

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

8. In a World Made of Steel

Although new to Europe in the Middle Ages, alchemy is rooted in metallurgy—creating alloys, metalworking techniques, etc. Europeans had centuries of knowledge and experience with this practice, so they were primed for the advent of alchemy.

9. My Nom de Plume Has a Nom de Plume

When European alchemists began writing their own texts, not just working from translations, they would frequently adopt Arabic pseudonyms, as the Islamic world had produced some of the most important work on alchemy by that time. Similarly, earlier generations of Islamic writers had used Greek pseudonyms, since Hellenic alchemists were the first foremost authorities on the subject. It’s pseudonyms all the way down.

10. Aristotle Says

Medieval alchemy was dogged by controversy from the beginning. Though there were arguments about alchemy before, around 1200 AD, an English edition of Aristotle’s Meteors was published in the same volume as an Arabic work denouncing alchemy. Many readers at the time mistakenly assumed that Aristotle was the author of both, and, not wishing to defy the “Father of Western Philosophy,” they were quick to denounce alchemy too.

11. Updating the Curriculum

The 13th-century monk Roger Bacon was an authority on subjects like comparative linguistics and medicine, but he also lobbied for the inclusion of less conventional subjects like alchemy and astrology into the medieval university curriculum. The course offerings at Hogwarts might not have seemed so farfetched to Bacon.

12. Talking Heads

Bacon’s fame lasted well beyond his end at the end of the 13th century, perhaps because legend portrayed him more as a powerful alchemist and magician than as a monk and scholar. One famous tale claims that Bacon assisted in creating a magical bronze bust that would answer any question it was asked—a sophisticated precursor of today’s magic eight ball.

13. No Girls Allowed (Anymore)

Although women alchemists were virtually non-existent in the Middle Ages, the very first alchemist on record is a woman known as Mary the Jewess, who was practicing around 200 AD. She is credited with various advances involving the heating and distillation of elements that are still used in some form by chemists today.

14. It’s All Greek to Me

Alchemists were a paranoid, secretive bunch, often jealously guarding their research by writing it in code, peppering it with misleading or deliberately false information, and using invented jargon.

Wikimedia.Commons

Wikimedia.Commons

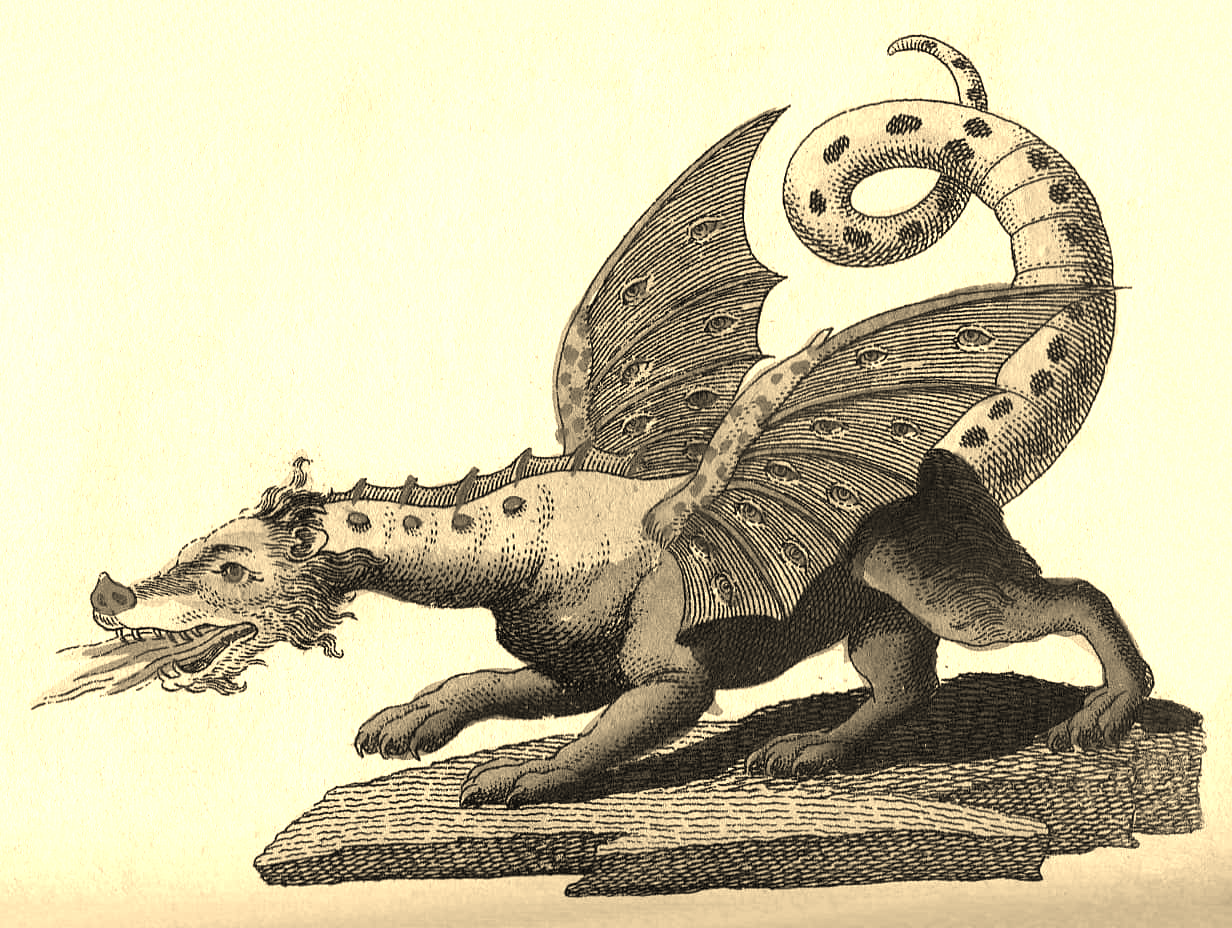

15. You Say Tomato, I Say Dragon’s Blood

Historians have now determined that certain unlikely sounding ingredients in alchemical recipes were actually shorthand for more regular things. “Dragon’s blood,” for example, refers to mercury sulfide, and “the black dragon” seems to represent a form of powdered lead.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

16. Not Your Typical Shopping List

A famous Medieval text, Theophilus' On Diverse Arts, includes a recipe for “Spanish Gold,” which is made from vinegar, red copper, human blood, and powdered basilisk, a mythical reptile that could end with its glance. And in case you’re thinking maybe powdered basilisk is code for something else, the author goes on to describe how you can obtain a basilisk—a process involving getting two roosters to mate, and giving the egg they produce to a toad for hatching.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

17. The Gift That Keeps on Giving

Some alchemists believed that the philosopher’s stone could do more than just provide wealth and immortality: one work contends that it can also turn glass from a solid to a flexible substance, thus bestowing, along with affluence and eternal life, the ultimate party trick. Even stranger though? Glass is an amorphous solid.

18. That’ll Cure What Ails You

Jean de Roquetaillade, a medieval monk, set his sights on finding a panacea, or cure-all, which he called aqua vitae, Latin for “water of life". He claimed to have succeeded in this venture, but no evidence of this remains, and the term aqua vitae is still used today to apply to extremely strong distillations of booze. Maybe he’d had a little too much to drink of his own panacea.

19. Rebel Alchemist With a Cause

De Roquetaillade was also a bit of an alchemical bad boy in the 14th century. He so completely offended two consecutive Popes, Clement VI and Innocent VI, with his dramatic prophecies and vehement denunciations of abuses within the church that despite his scholarly reputation, he spent most of his later days behind bars.

20. Who You Calling Betrüger?

Later on in its tenure, the alchemical profession attracted its share of fakes and charlatans—so much so that in Germany there was even a term, betrüger, which meant “fraudulent alchemist". Today the term is still in use, but means simply “fraudster".

21. Law and Order

Pope John XXII took a special interest in protecting people from sinister, blasphemous alchemists. The pope issued an edict in 1317 that specifically prohibited false claims of the alchemical ability to change metals into gold.

22. Do You Have a Permit for That?

Almost a century after Pope John XXII banned false alchemy, King Henry IV of England took things a step further and in 1403 outlawed the transmutation of metals altogether. You could only practice alchemy if you got a special license.

23. Insult to Injury

In England, if an alchemist was caught practicing without a license, punishments included decking out the offender in tinsel and executing them by hanging them from a gilded scaffold. Who says the law has no sense of humor?

24. Alchemy Schmalchemy

Medieval literary greats like Dante and Chaucer didn’t think much of alchemists, taking potshots at them in their writing. Chaucer’s “Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale” from The Canterbury Tales tells the story of a foolish man who wastes his life on alchemical studies, and Dante vision of inferno includes lying, cheating alchemists.

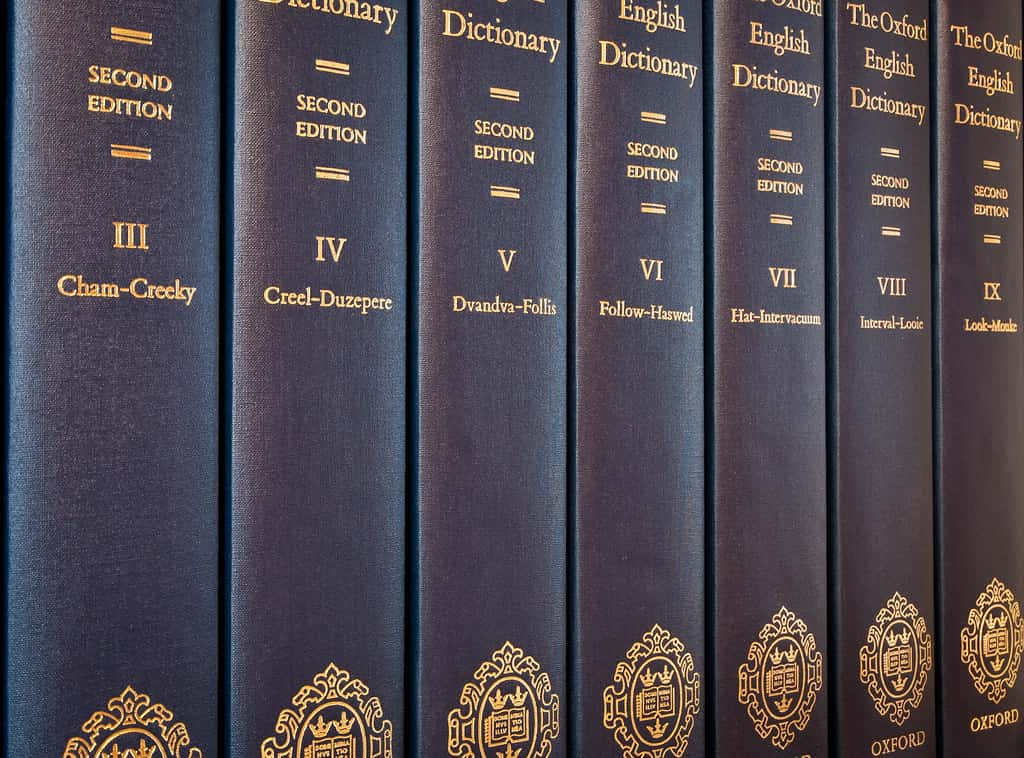

25. Alchemy Is a Four-Letter Word

The sheer number of alchemists running around just after the Middle Ages, most of whom were now seen as phony, led to the introduction of a new definition for the word “alchemy". The Oxford English Dictionary gives the year 1547 as the first recorded use of the term to mean “glittering dross; superficial trickery; deceptive cleverness".

26. A Comedy of Errors

Ben Jonson, considered by many to be England’s first Poet Laureate, wrote a play called The Alchemist about a group of swindlers featuring a charlatan alchemist. More than 200 years after Chaucer’s satire on alchemists in The Canterbury Tales, they were still the behind of literary jokes.

27. Member of the Nobility

Alchemy is also referred to as the “Noble Art” because of its goal to change regular metals into “noble” metals like gold.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock

28. The Mona Lisa of Alchemy

The Latin phrase magnum opus, which we use today to mean “great work” or “masterpiece,” was also sometimes used in alchemy. The magnum opus sometimes referred to the process of creating the philosopher’s stone, alchemy’s ultimate project.

29. Lead Into Gold, Water Into Grape beverage

Some medieval alchemists connected their work to Christianity. They emphasized the connection between the transformative power of alchemy, transmuting base metals into valuable metals, and the transformative power of Christ, transmuting sinners into the saved.

30. The Alchemist Will See You Now

Modern medicine would look very different without Paracelsus, a 16th-century alchemist and physician, whose belief in the importance of balancing elements led him to discoveries about the prevention of infection. It was common practice to apply poultices of animal waste to open wounds, and Paracelsus was one of the first to suggest, “hey, maybe let’s skip the cow dung part of the treatment".

31. Maybe She’s Born With It, Maybe It’s Alchemy

Discoveries in alchemy contributed to more than just the sciences: alchemists experimented with the creation and modification of pigments, dyes, and perfumes that were important to fashion, cosmetics, décor, and art.

Flickr

Flickr

32. Hark the Herald Angels Sing

In some later permutations of alchemy, certain alchemists had strong ties to the mystic, the spiritual, and even the occult. Some acolytes believed that the philosopher’s stone could act as a hotline to heaven and be used to talk to, and even summon, angels.

33. Making Friends and Influencing People

Highly successful alchemists, particularly just after the Middle Ages, often served as consultants to royalty. It became fashionable in court circles to secure the services of a private alchemist, much like celebrities today might keep a personal medical or law team on retainer.

34. It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s…an Alchemist

King James IV of Scotland employed alchemist John Damian, and built a workshop in his castle where Damian could conduct his experiments. Some of these involved aviation and aerodynamics, allegedly culminating in Damian's attempt to fly from the castle ramparts. The fact that he only broke his thigh as opposed to his neck I think justifies King James’s faith in Damian’s abilities.

35. Are You There, God? It’s Me, John Dee

Although he was an accomplished mathematician and cryptographer, John Dee, advisor to Queen Elizabeth I, was renowned for his alchemical and occult pursuits. Dee specialized in divination and astrology, and spent the last third of his life attempting to communicate with angels so he could learn the universal language of creation.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

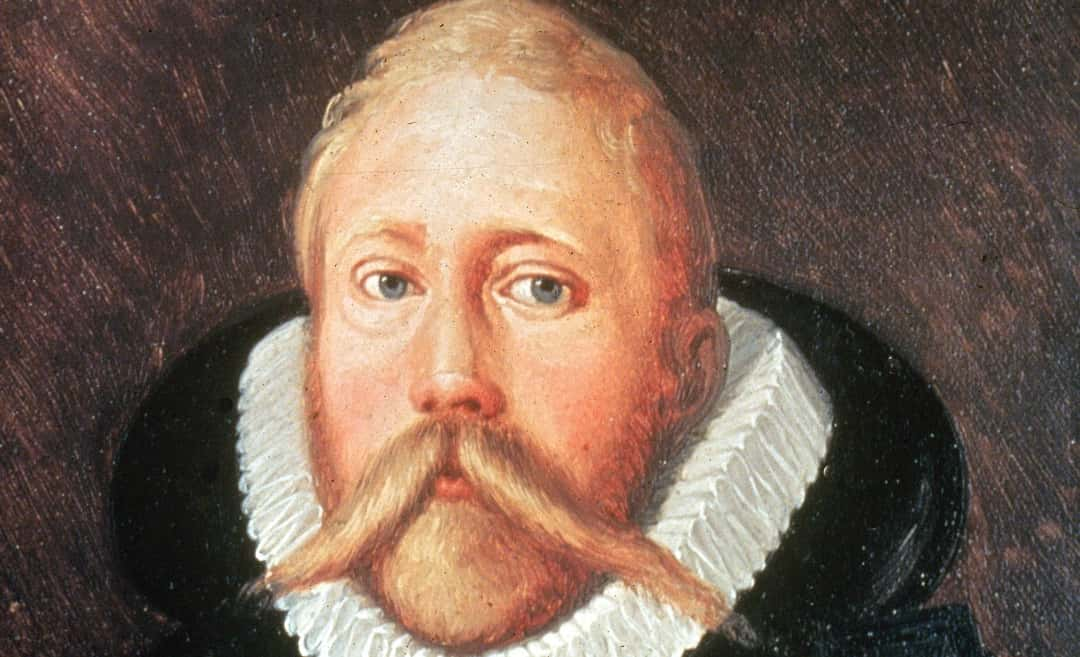

36. Gentlemen Prefer to Be Blondes

16th-century Danish noble Tycho Brahe is best known for his major contributions to astronomy, but he was also an enthusiastic alchemist. Scientists have theorized that this explains why, when Brahe perished , his hair, beard, and eyebrows contained traces of gold—something like 20-100 times the amount found in a normal human today.

37. Who, Me?

Nicolas Flamel, a wealthy French bookseller who lived from around the 1330s to the 1410s, is known as one of the most famous alchemists in history, but there is no evidence that he actually had anything to do with alchemy. Despite the facts, Flamel’s reputation as a master alchemist is perpetuated today by popular works like Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, where he features as Dumbledore’s collaborator in researching immortality.

38. Bernard the Teenage Alchemist

Bernard Trevisan, a 15th-century Italian aristocrat, received his family’s blessing to pursue alchemy when he was just 14 years old. He spent decades and his entire family fortune trying to create the philosopher’s stone, and he was still trying when he perished in deteriorated health, probably as a result of his alchemical experiments.

39. The Secret Ingredient Is...You Don't Want to Know

Trevisan’s alchemical attempts in the mid-1400s led him to pursue a variety of strange recipes. He and a colleague spent eight years using the shells and yolk of chicken eggs, “purified” in horse manure, to try to create the philosopher’s stone. When that didn’t work, he started using human blood and urine instead to try out his experiments. Not a profession for the faint of heart.

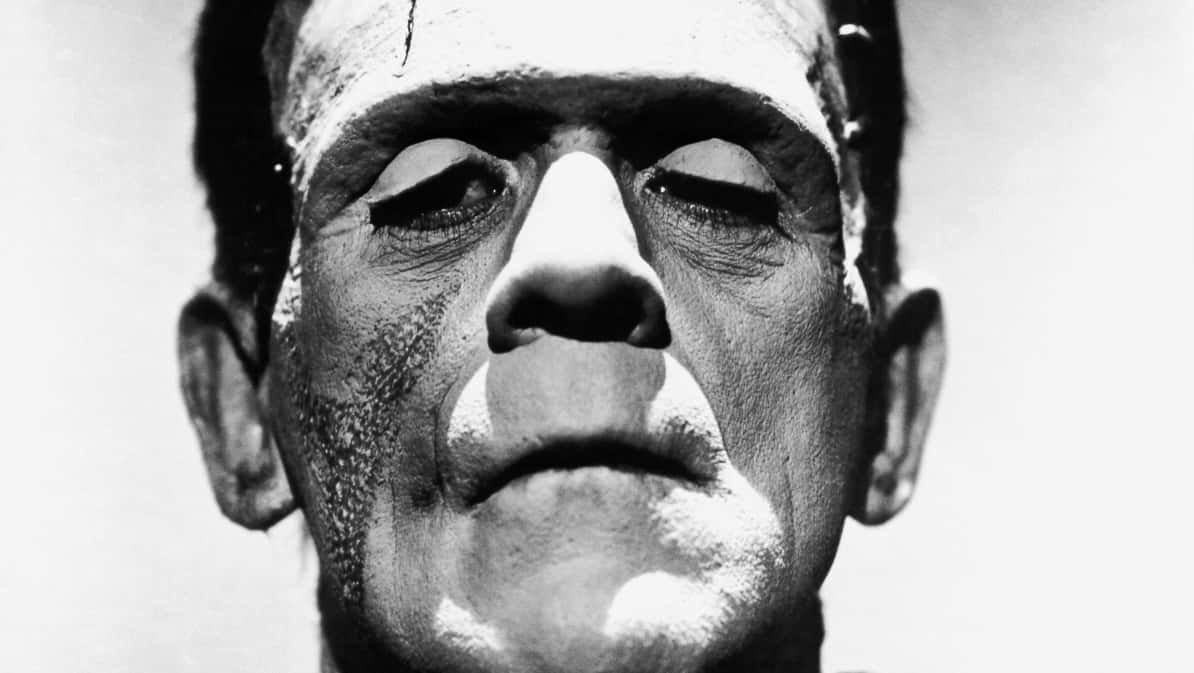

40. The Decline and Fall of the Alchemical Empire

The mid-18th century was the beginning of the end for alchemy. By 1818 and the publication of Frankenstein, which portrays the mad scientist as basing his monster project on the work of famous alchemists, the discipline was considered to be solely the domain of crackpots, quacks, and con artists.

41. One Man’s Bodily Waste Is Another Man’s Treasure

In his quest for the philosopher’s stone, 17th-century German alchemist experimented with distilling and processing urine. While this didn’t lead to immortality and wealth, it did help him discover phosphorus, left over as a powdered residue from the distillation experiments. It may not be the philosopher’s stone, but campers everywhere are grateful for a discovery that led to the invention of matches.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24