Unplanned Discovery Zone

Antarctic ice hides what's happening in the ocean below. A yellow robot accidentally drifted under those frozen barriers and survived eight months of darkness. The temperature readings it brought back revealed something alarming.

Joe Mabel, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Joe Mabel, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Argo Network

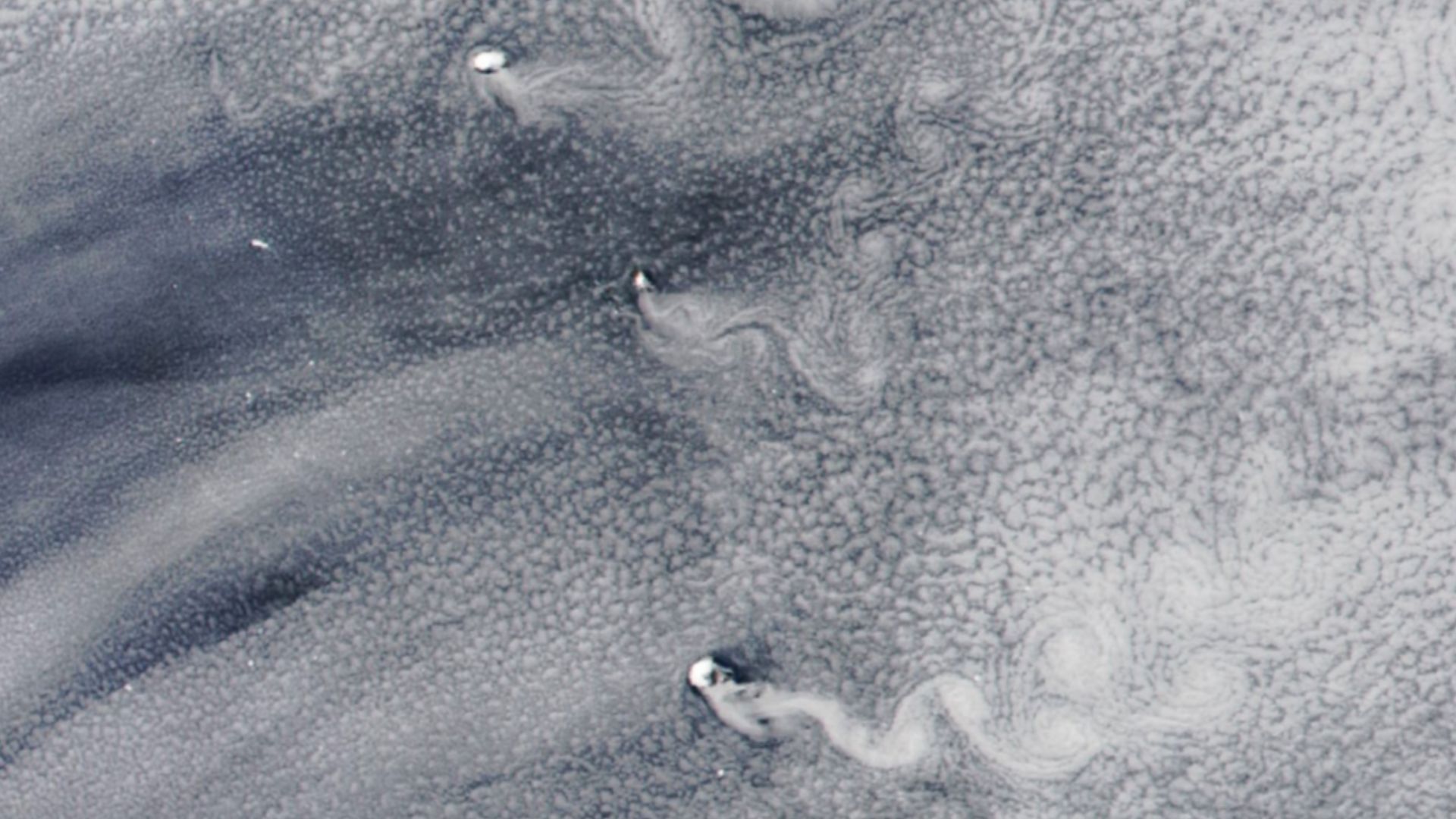

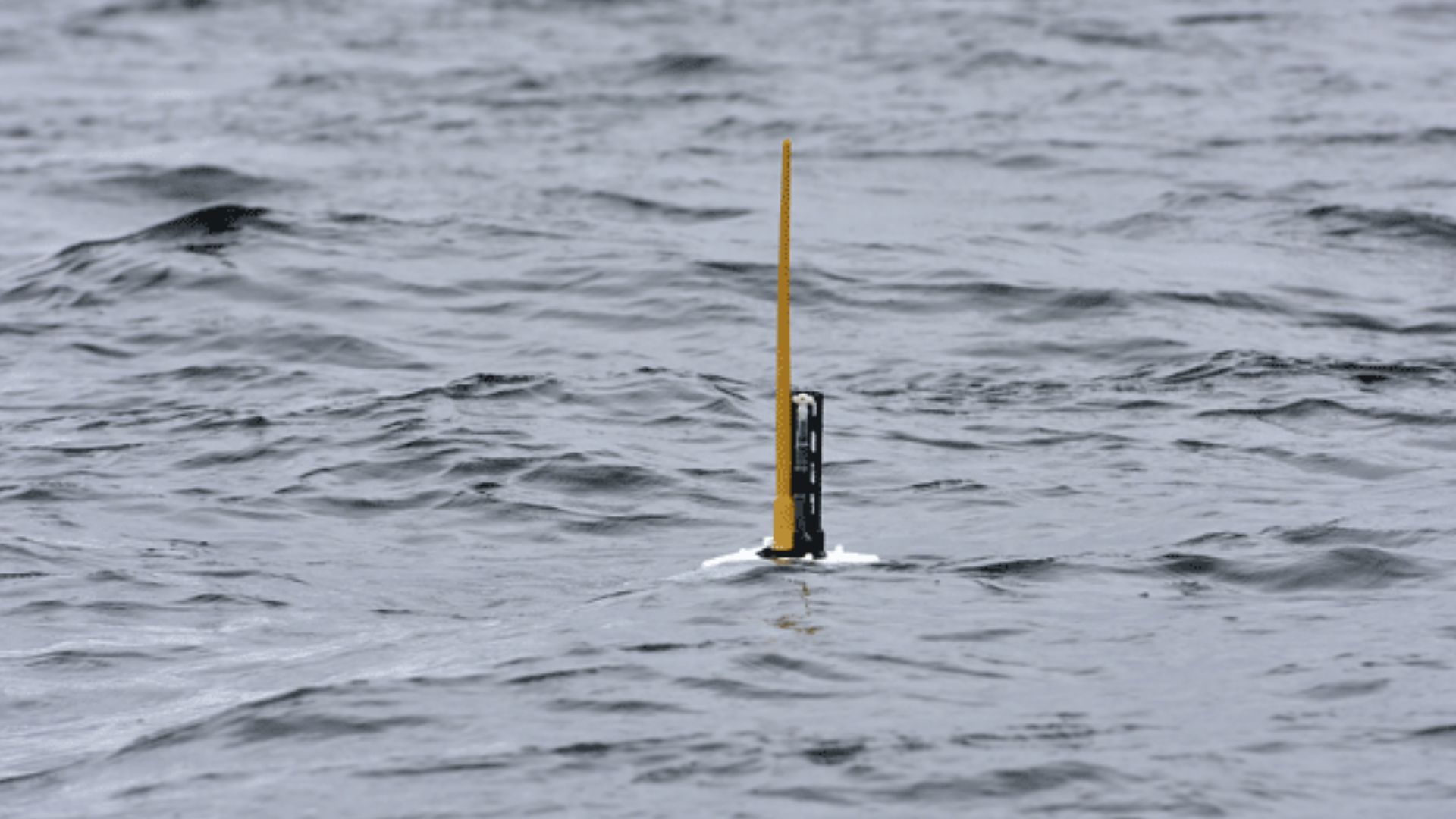

Picture around 4000 yellow robotic cylinders bobbing through Earth's oceans right now, silently collecting data that helps us understand our warming planet. These Argo floats dive up to two kilometers deep, resurface every ten days to transmit findings via satellite, then plunge back down.

Bruce Miller, CSIRO, Wikimedia Commons

Bruce Miller, CSIRO, Wikimedia Commons

Antarctic Monitoring

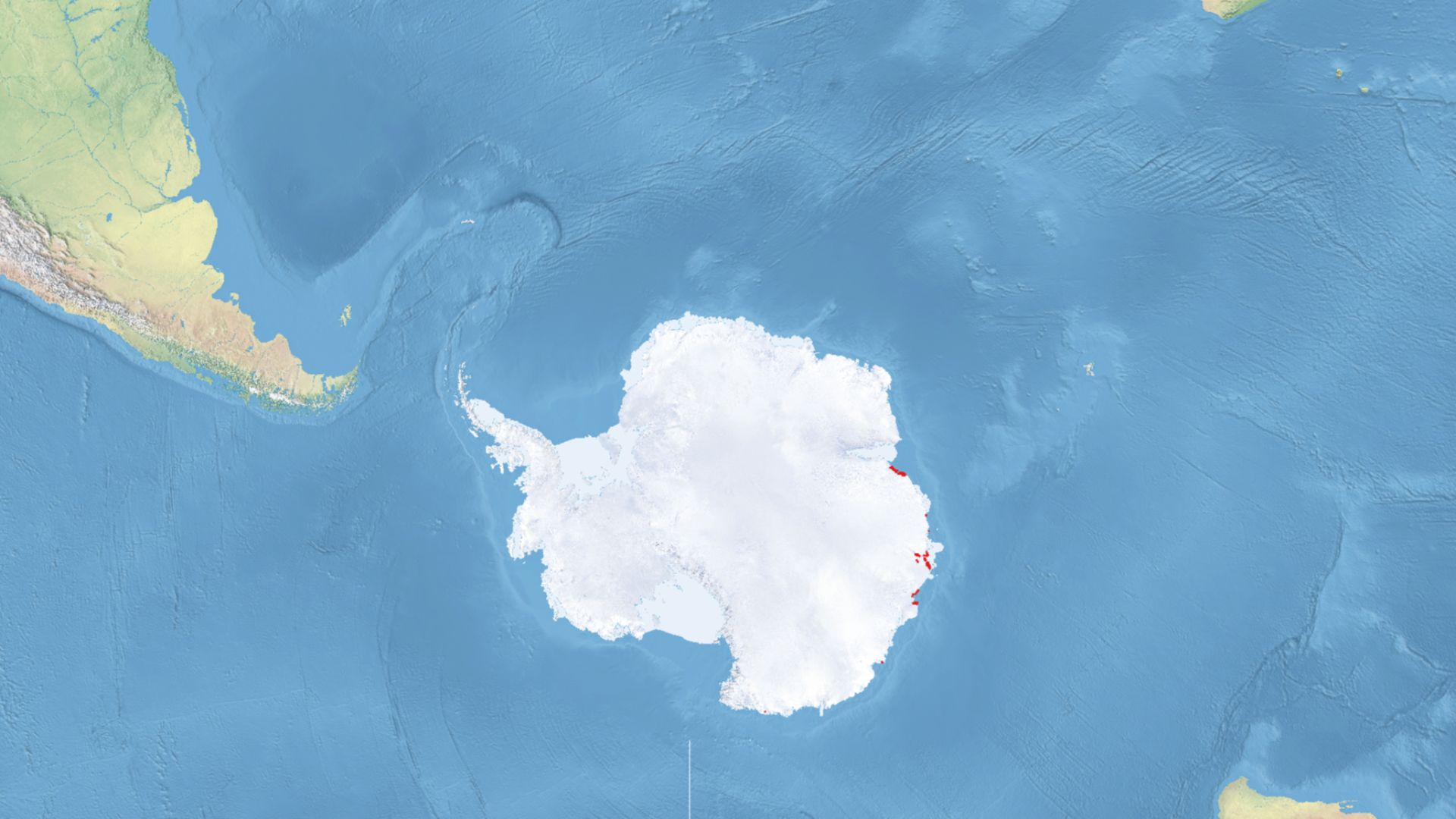

East Antarctica holds 80% of Earth's continental ice, which is enough to increase global sea levels by 60 meters if completely melted. Scientists once believed this sector was stable, safely grounded above sea level. Recent discoveries shattered that comfort: East Antarctica contains five times more vulnerable marine-based ice than West Antarctica.

CSIRO Agency

Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation deployed a specialized Argo float in 2020, partnering with the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership and the University of Tasmania. Dr Steve Rintoul, a veteran CSIRO oceanographer, led the mission team.

East Antarctica

The Shackleton Ice Shelf spans 26,182 square kilometers, making it the third-largest and most northerly ice platform in East Antarctica. Fed by outlet glaciers draining the Aurora Subglacial Basin, this massive floating ice shelf was historically dismissed as stable. The region remained Antarctica's “sleeping giant”.

Andrew J Walder, Wikimedia Commons

Andrew J Walder, Wikimedia Commons

September 2020

On a crisp Antarctic spring day, researchers lowered their Argo float into frigid waters near the continental shelf. The deployment seemed routine. Thousands of similar floats had been released worldwide without incident. This particular device carried standard oceanographic sensors designed to measure temperature, salinity, pressure, oxygen, pH, and nitrate levels.

Antti Leppänen, Wikimedia Commons

Antti Leppänen, Wikimedia Commons

Totten Target

The mission's objective was crystal clear: measure ocean heat reaching Totten Glacier, East Antarctica's largest ice outlet and one of the fastest-thinning glaciers on the continent. Totten drains a catchment spanning 538,000 square kilometers. Its ice volume alone could raise global sea levels by 3.5 meters.

Marinha do Brasil, Wikimedia Commons

Marinha do Brasil, Wikimedia Commons

Deployment Plan

Well, the float was programmed to follow Argo's standard 10-day cycle: drift at 1,000 meters depth for approximately nine days while taking periodic measurements, then descend to 2,000 meters before slowly ascending. During each rise to the surface, it measured conductivity, temperature, and pressure throughout the water column.

Current Drift

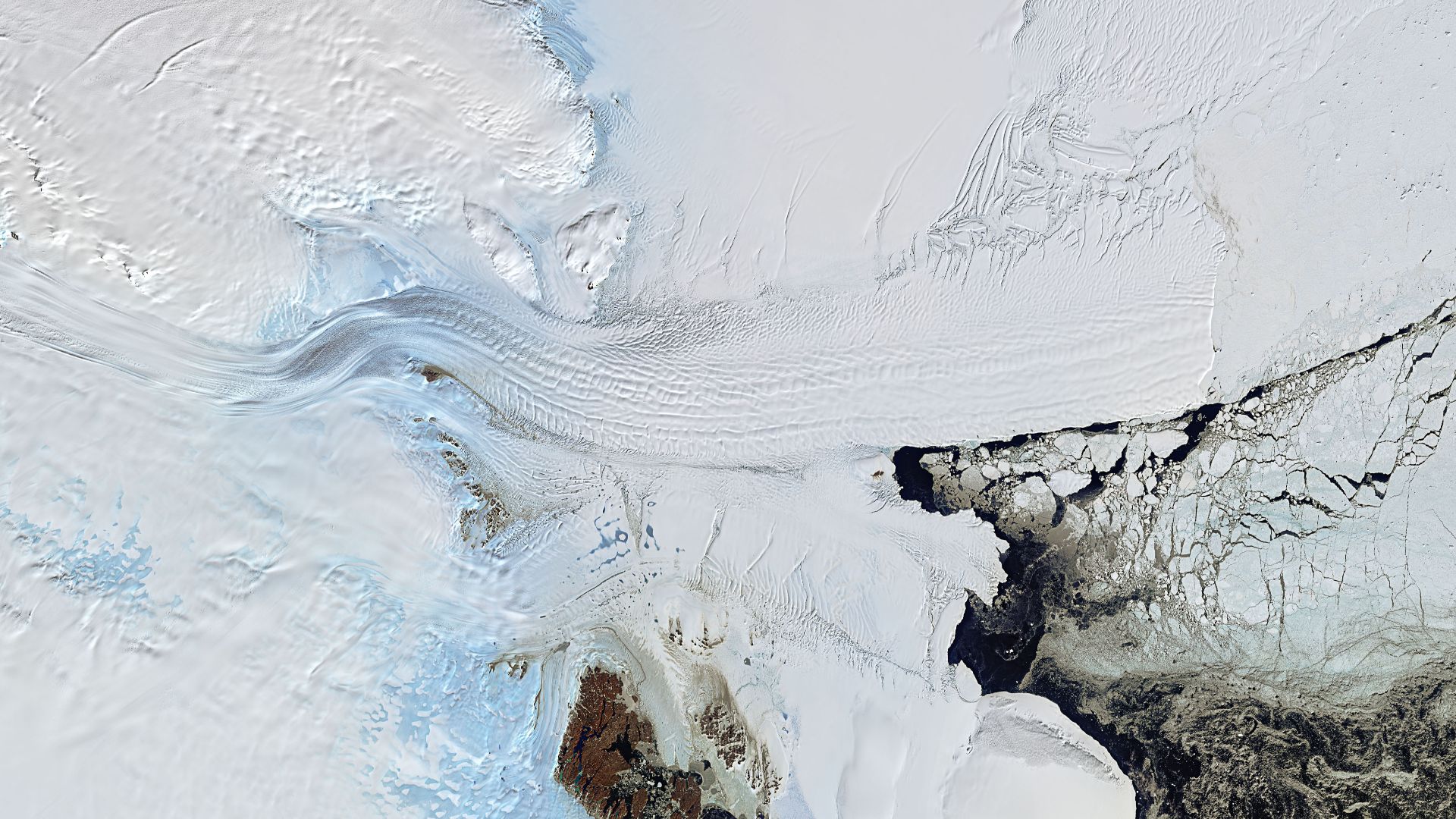

Within days of deployment, something went wrong—or incredibly right, depending on perspective. Unpredictable Antarctic tides and ocean currents seized the float, dragging it westward away from Totten Glacier. Instead of monitoring its intended target, the device drifted toward the Denman and Shackleton ice shelves.

Lost Contact

The float's GPS signal vanished in late 2020 as it slipped beneath the Denman Ice Shelf's massive frozen ceiling. Without the capability to surface, it couldn't communicate with satellites or update its position. "We feared the worst," the research team later admitted. For eight months, there was complete radio silence.

NASA/J. Sonntag, Wikimedia Commons

NASA/J. Sonntag, Wikimedia Commons

GPS Blackout

Trapped under ice potentially thousands of meters thick, the float became invisible to modern tracking technology. Its pre-programmed sensors continued collecting temperature and salinity profiles every five days, dutifully storing data in internal memory with no way to transmit findings. The team had no idea if the device was still functioning.

ISS Expedition 29 crew, Wikimedia Commons

ISS Expedition 29 crew, Wikimedia Commons

Eight Months

During its subterranean odyssey, the float navigated a landscape scientists call an "ice shelf cavity"—cathedral-sized chambers where seawater circulates below floating glacial ice in total darkness. The device drifted westward at depths of two kilometers, driven by thermohaline currents generated by temperature and salinity differences.

Feared Forever

By mid-2021, the research team had written off the float as a total loss. Antarctic ice shelves can be hundreds to thousands of meters thick. Drilling through such massive ice to recover instruments is prohibitively expensive and rarely attempted. Previous floats lost under ice had never returned.

March 2023

Then, against all odds, a satellite signal pinged. The float had resurfaced after 30 months of deployment, including those eight mysterious months under the ice. "We got lucky," Dr Rintoul admitted with characteristic understatement. The device bobbed in open water, intact and functional, its memory banks full of data.

John Masterson, CSIRO, Wikimedia Commons

John Masterson, CSIRO, Wikimedia Commons

Miraculous Resurface

Scientists could barely believe their instruments were receiving genuine data from beneath the ice of Denman and Shackleton. For decades, researchers had relied on educated guesses about conditions in these ice shelf cavities, using satellite measurements and computer models to fill knowledge gaps. Now they had direct observations.

NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center / NASA/Jim Ross, Wikimedia Commons

NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center / NASA/Jim Ross, Wikimedia Commons

195 Profiles

The device had collected 195 complete vertical profiles spanning 2.5 years of deployment. Each profile captured water properties from the ocean floor up to the ice shelf base, revealing the structure of water masses, circulation patterns, and heat distribution.

U.S. Department of State from United States, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Department of State from United States, Wikimedia Commons

Unprecedented Data

This represented the first line of oceanographic measurements beneath any ice shelf in East Antarctica—a region containing enough ice to reshape every coastline on Earth. The float had measured the important 10-meter-thick "boundary layer" immediately below the ice shelf, where heat transfer from ocean to ice determines melt rates.

Shackleton Stability

Additionally, the data revealed surprisingly good news for the Shackleton Ice Shelf—the northernmost ice platform in East Antarctica. Water temperatures at the surface freezing point were driving only weak, widespread melting from below. Warm Circumpolar Deep Water was not reaching the ice shelf base, meaning Shackleton remains protected for now.

Denman Vulnerability

In stark contrast, Denman Glacier tells a terrifying story. The float detected warm water actively reaching the glacier's underside, driving strong basal melting. Denman drains ice equivalent to 1.5 meters of global sea level rise, enough to submerge countless coastal cities and displace hundreds of millions of people.

Warm Water

Modified Circumpolar Deep Water enters the Denman cavity along the eastern side of Denman Trough, bringing temperatures between minus 0.5 and 1 degrees Celsius. This warm layer's thickness controls melt rates with frightening sensitivity. The float data showed Denman is "delicately poised".

Boundary Layer

Scientists discovered something intriguing within this thin interface: salinity gradients that facilitate warm water intrusion through a process called "salt fingering," where density instabilities create turbulent mixing. The boundary layer acts like a thermal blanket with holes.

United States Antarctic Program, Wikimedia Commons

United States Antarctic Program, Wikimedia Commons

1.5 Meter

So, if Denman Glacier completely melted or slid into the ocean, global coastlines would retreat inland by 1.5 meters. This would be a catastrophic scenario that would permanently flood major river deltas like the Ganges, Mekong, and Nile.

Hossam el-Hamalawy, Wikimedia Commons

Hossam el-Hamalawy, Wikimedia Commons

Further Damage

Low-lying island nations, including the Maldives, Tuvalu, and Marshall Islands, would cease to exist. Cities like Miami, Shanghai, Amsterdam, and Bangkok would require massive seawall construction costing trillions of dollars. The float data suggest this isn't hypothetical.

Amilla Maldives, Wikimedia Commons

Amilla Maldives, Wikimedia Commons

Coastal Cities

Over 600 million people currently live in low-elevation coastal zones less than 10 meters above sea level, with that number projected to reach one billion by 2050. The economic value of assets in these zones exceeds $20 trillion globally. Denman's potential contribution alone would inundate portions of New York City's subway system.

Billy Hathorn, Wikimedia Commons

Billy Hathorn, Wikimedia Commons

Future Floats

The mission's accidental success has inspired plans to deploy additional Argo floats along Antarctica's continental shelf throughout 2026. CSIRO researchers aim to monitor glaciers, including Moscow and additional sections of Totten, targeting regions where warm water pathways remain unmapped.

Argo Data Management, Wikimedia Commons

Argo Data Management, Wikimedia Commons

Climate Models

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has consistently cited the Antarctic contribution as the largest uncertainty in forecasting future sea levels through 2100 and beyond. Updated models now show narrower prediction ranges, giving coastal planners more confidence when designing infrastructure meant to last decades in an uncertain climate future.