The True Story Of The Titanic’s Tragic Twin

The RMS Olympic was the sister to the Titanic and the Britannic—two ships that met tragic ends. It had an illustrious career beginning in 1911. It tried to help rescue survivors during the sinking of the Titanic, was the subject of a historic strike, and also played a pivotal role in WWI.

But, like something out of a movie, fate eventually came for the Olympic as well—and when it did, it was absolutely devastating.

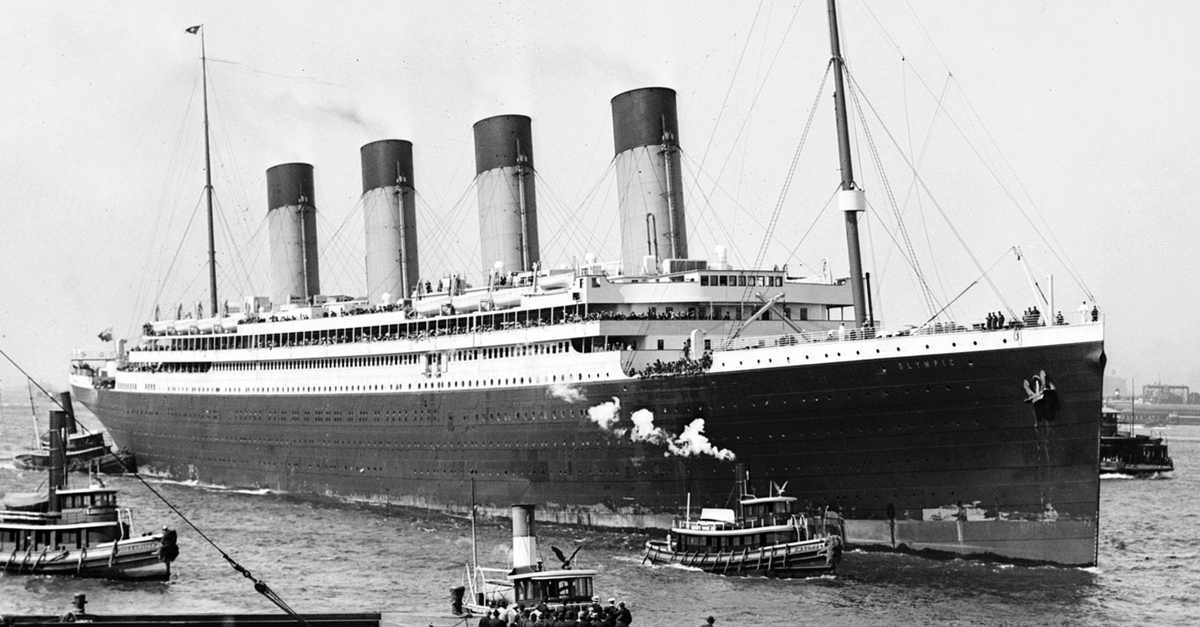

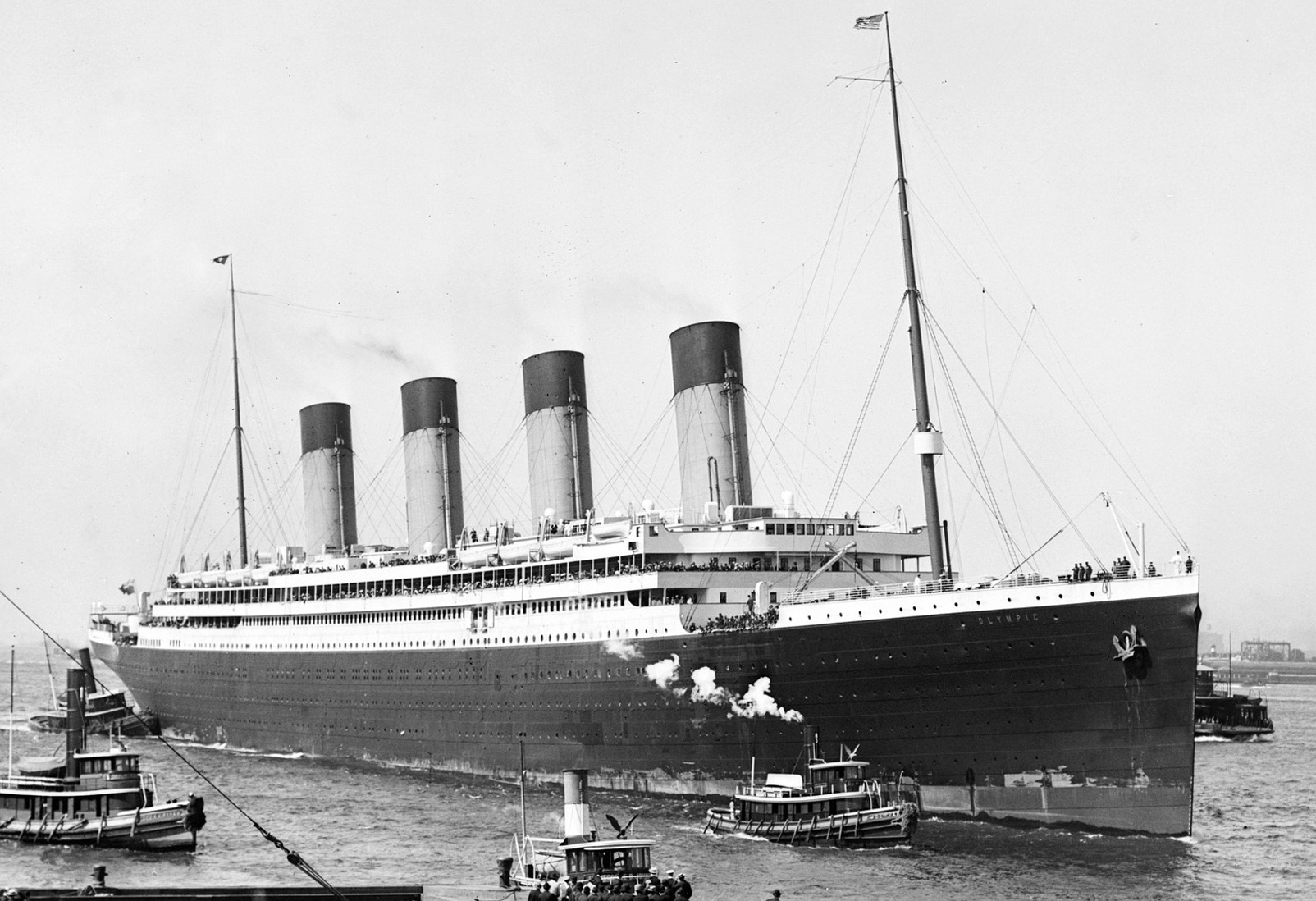

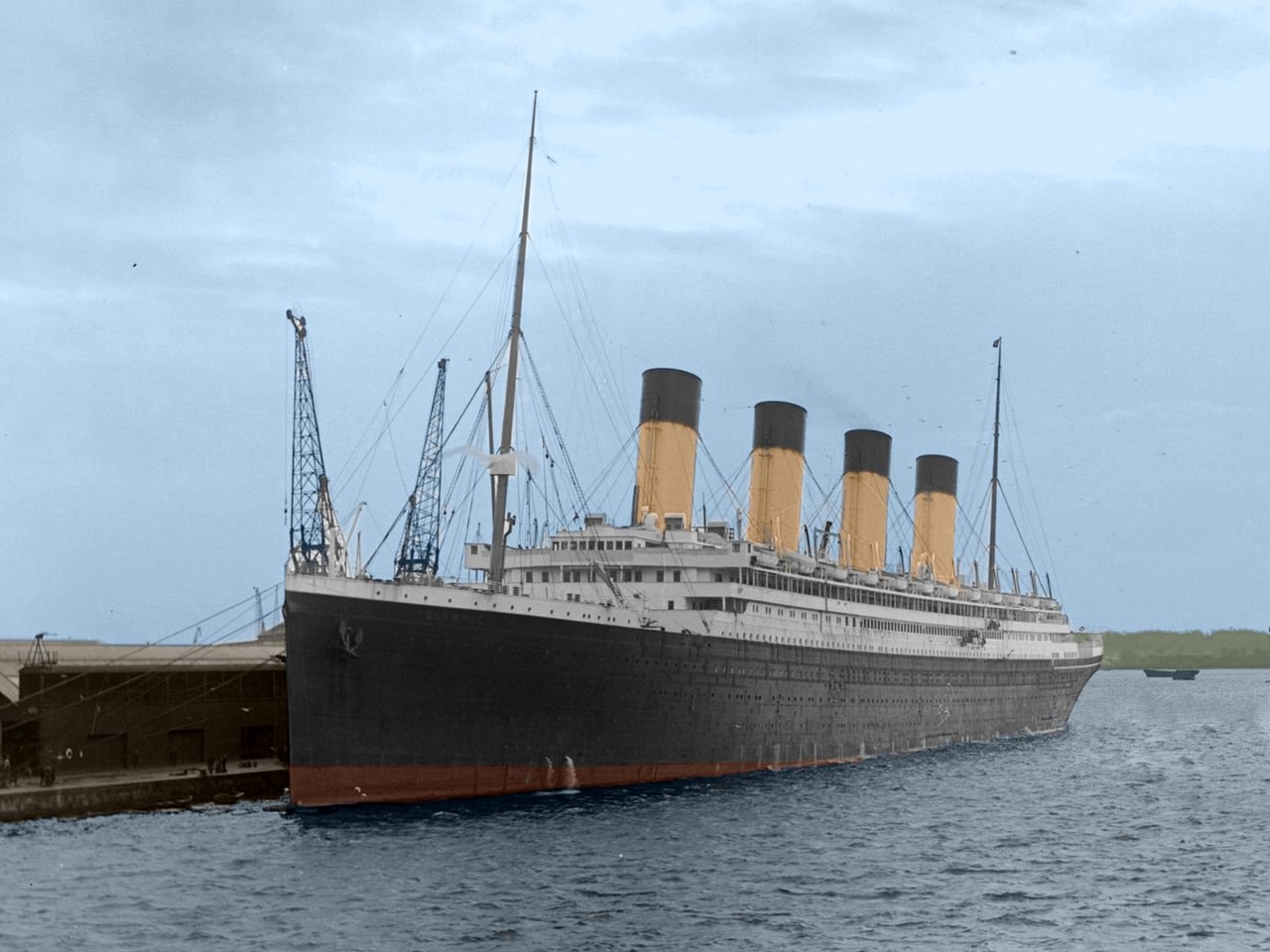

The Largest Ship In The World

For the first few years of its life, the RMS Olympic was the world’s largest ocean liner. For a brief period, the Titanic was larger—but we all know what happened there. After the Titanic sank, the Olympic gained its old title back until 1913, when Germany’s SS Imperator was launched. But though it only had a brief tenure as the largest ocean liner, it had a long and storied career.

Paul Thompson, Wikimedia Commons

Paul Thompson, Wikimedia Commons

“We’re Gonna Need A Bigger Boat”

In the first years of the 20th century, the White Star line faced increasing competition, primarily from Cunard, the British shipping and cruise line, which had just introduced two incredibly fast passenger ships, the Lusitania and the Mauritania. That was when White Star Line’s chairman came up with a plan to go head to head with them—and win.

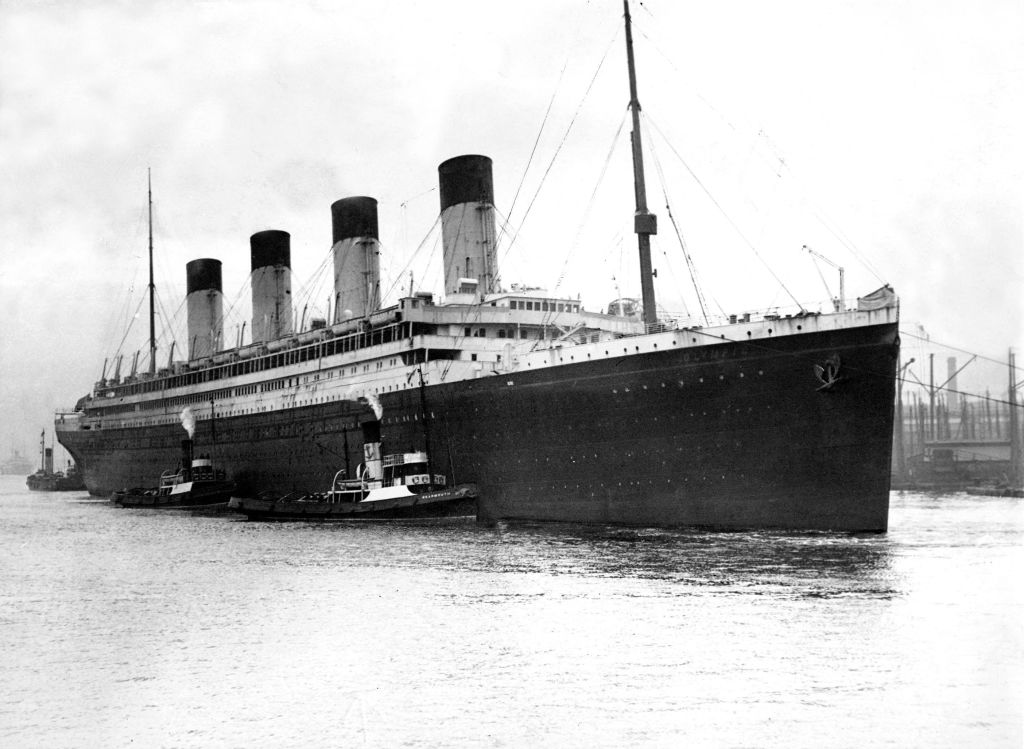

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Size Matters

Cunard’s ships were known for their speed—and if the White Star Line couldn’t compete with them on that, they’d have to be better in other ways. They wanted their ships to be bigger and more luxurious to appeal to customers who wanted a comfortable, palatial experience on the water as they traveled.

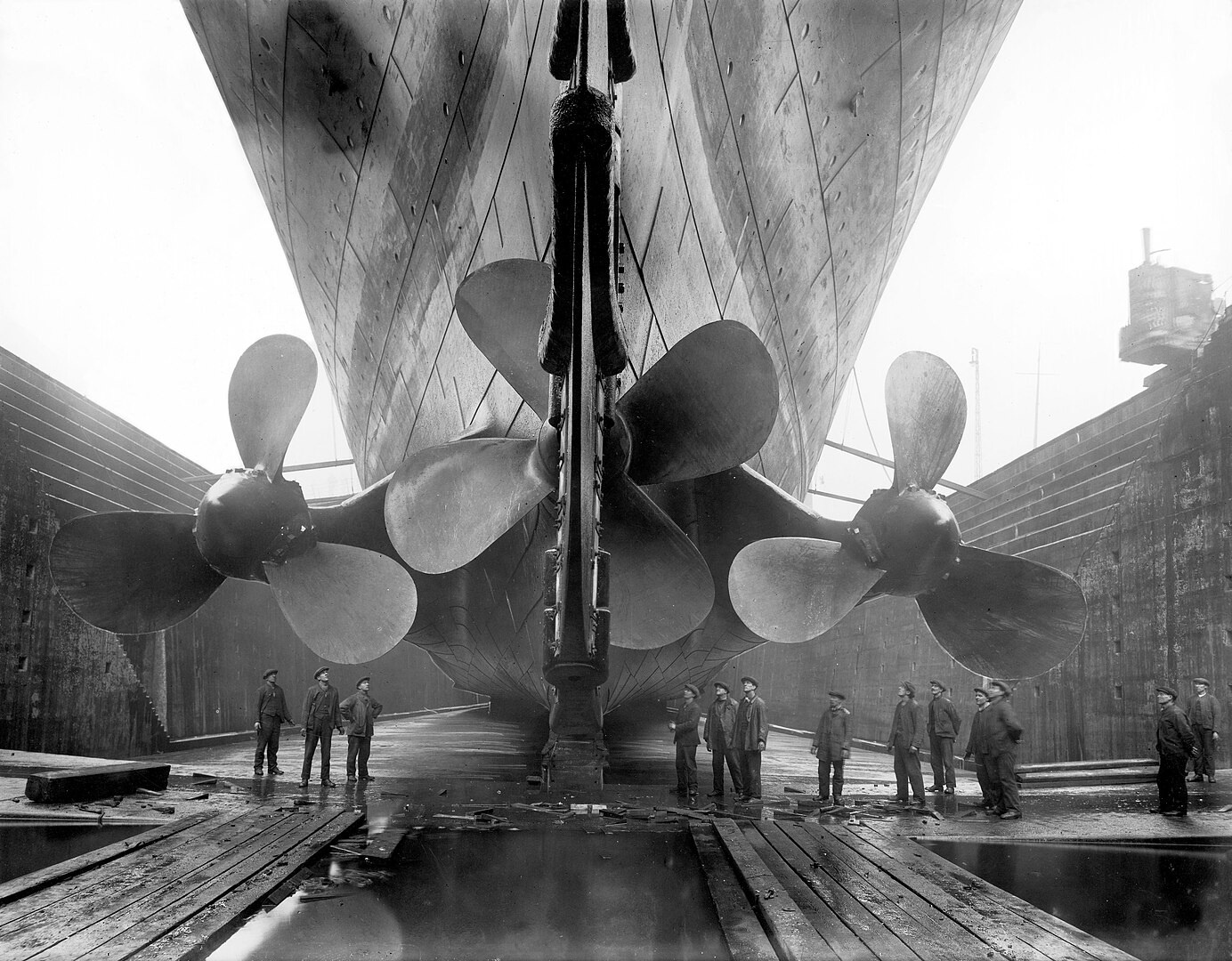

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

The Budget

White Star Lines collaborated with long-time partners Harland and Wolff, an Irish shipbuilding company. When it came to building the Olympic, money was no object. White Star said, “How much do you need”? and Harland and Wolff came back with a figure of £3 million for the first two ships, plus extras as needed and their usual 5% fee.

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Number 400

When the contracts were signed, the boat was as yet unnamed—so it was nicknamed Number 400, to reflect the fact that it was the 400th hull that Harland and Wolff had produced. They then revised the designs slightly to begin buildings its even bigger sister ship, the Titanic. Harland and Wolff expanded their headquarters and three months after they started building the Olympic, they started to work on the Titanic as well.

They didn’t know it then, but the fates of these two ships would forever be tied together.

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

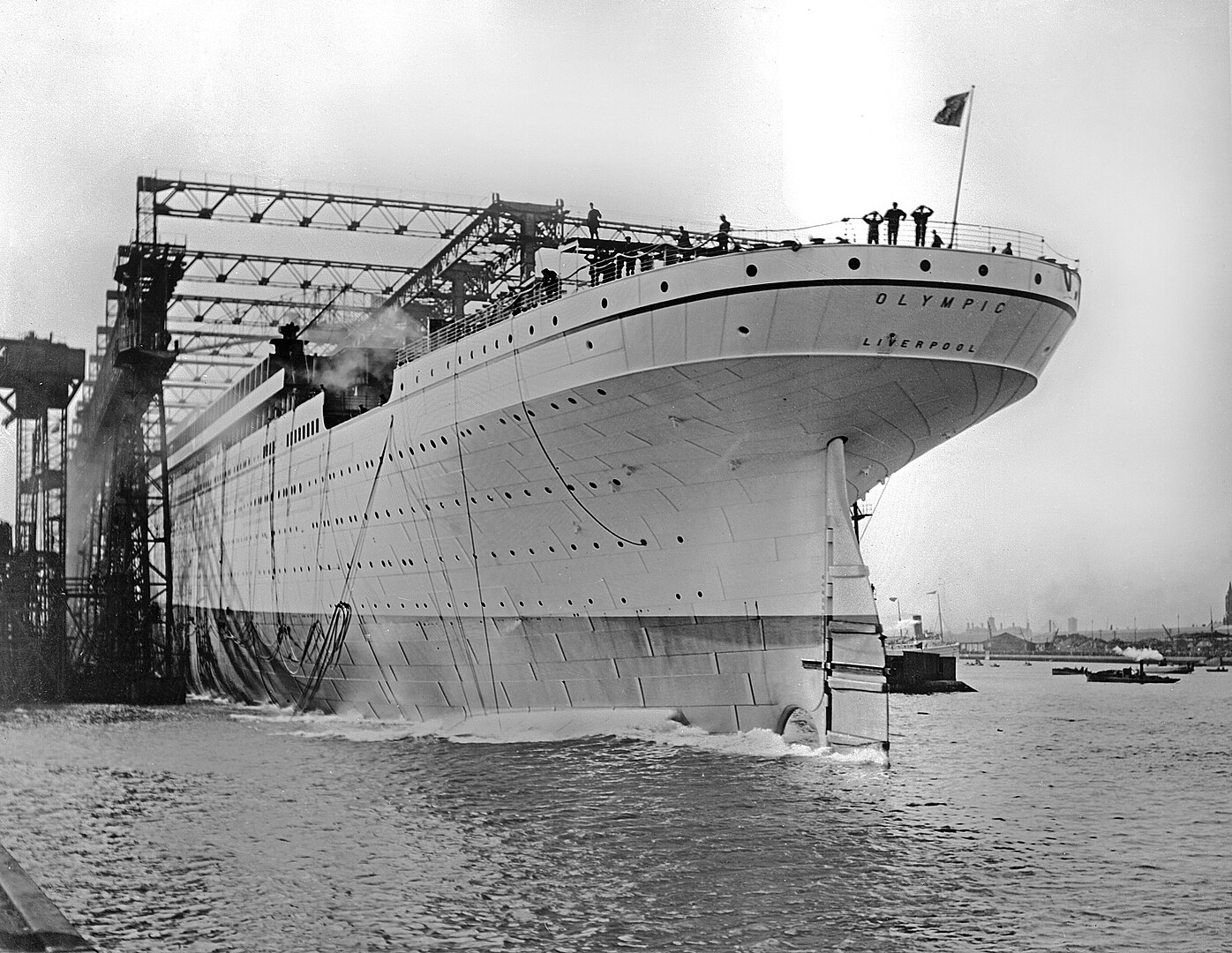

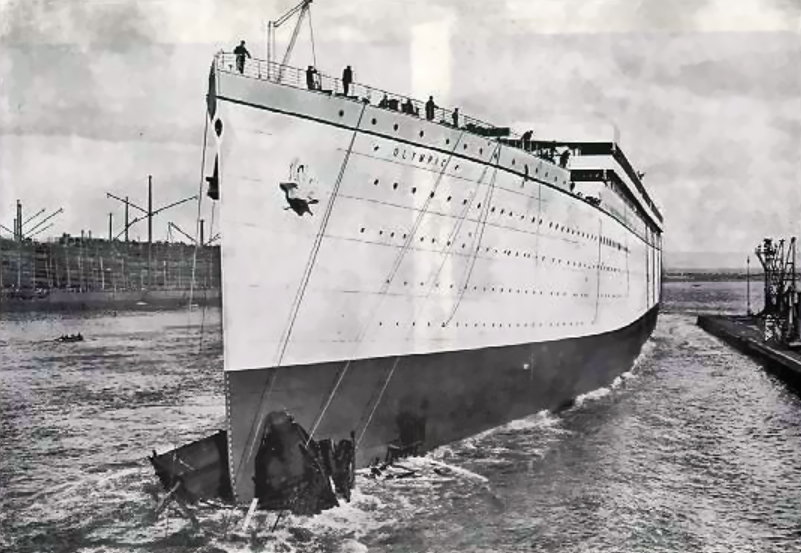

The First Launch

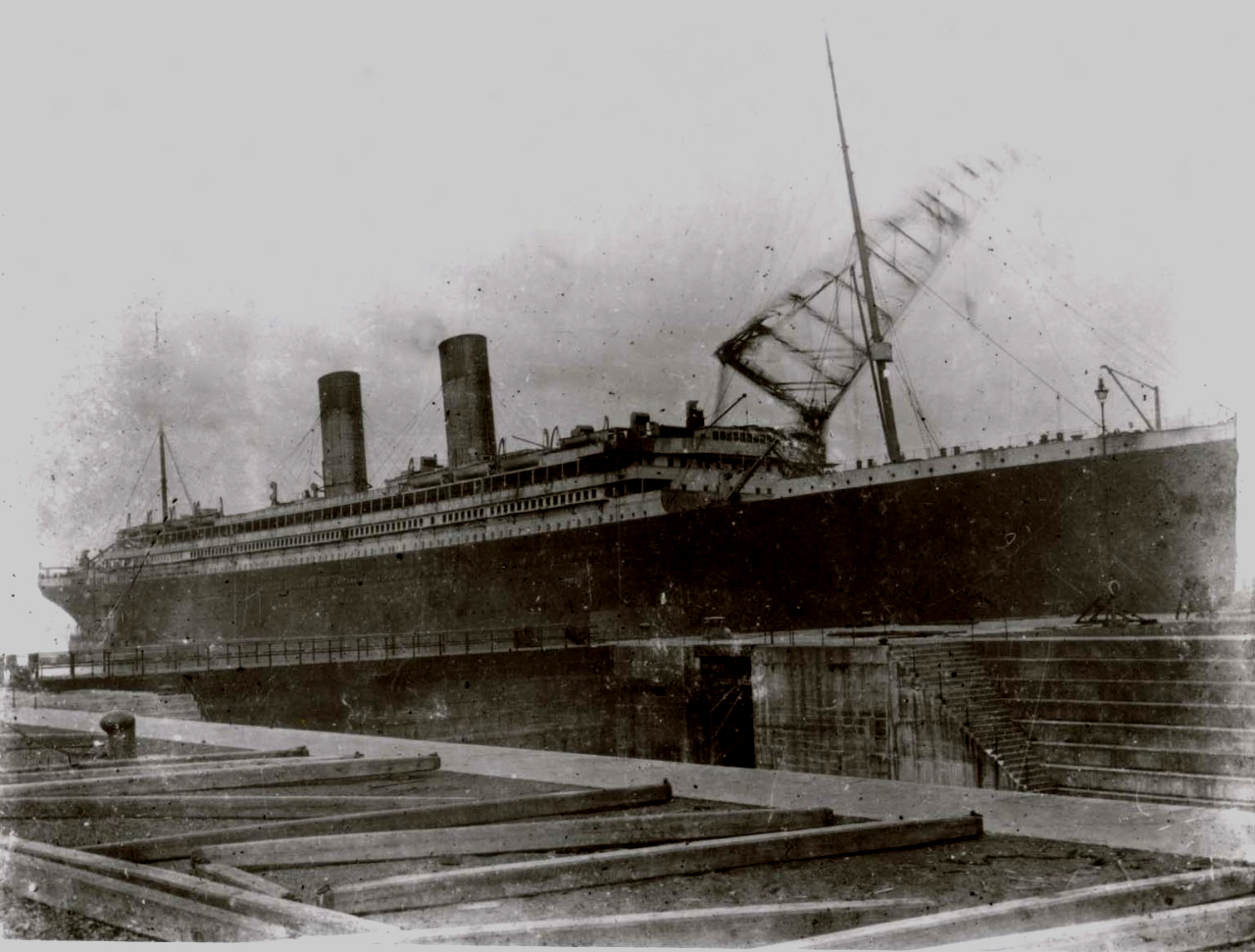

Just under two years later, White Star Line launched the then-unchristened ship, as per their tradition. It went out on the water essentially as a shell with a light gray hull—all the better to photograph. Then, it was dry docked and prepared for its real launch, which would come later.

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

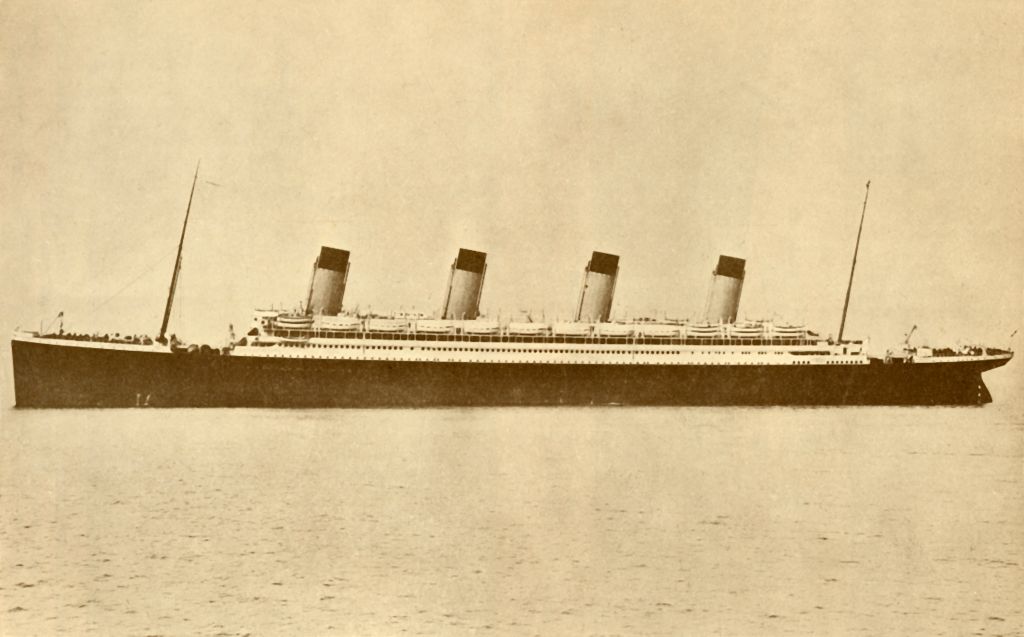

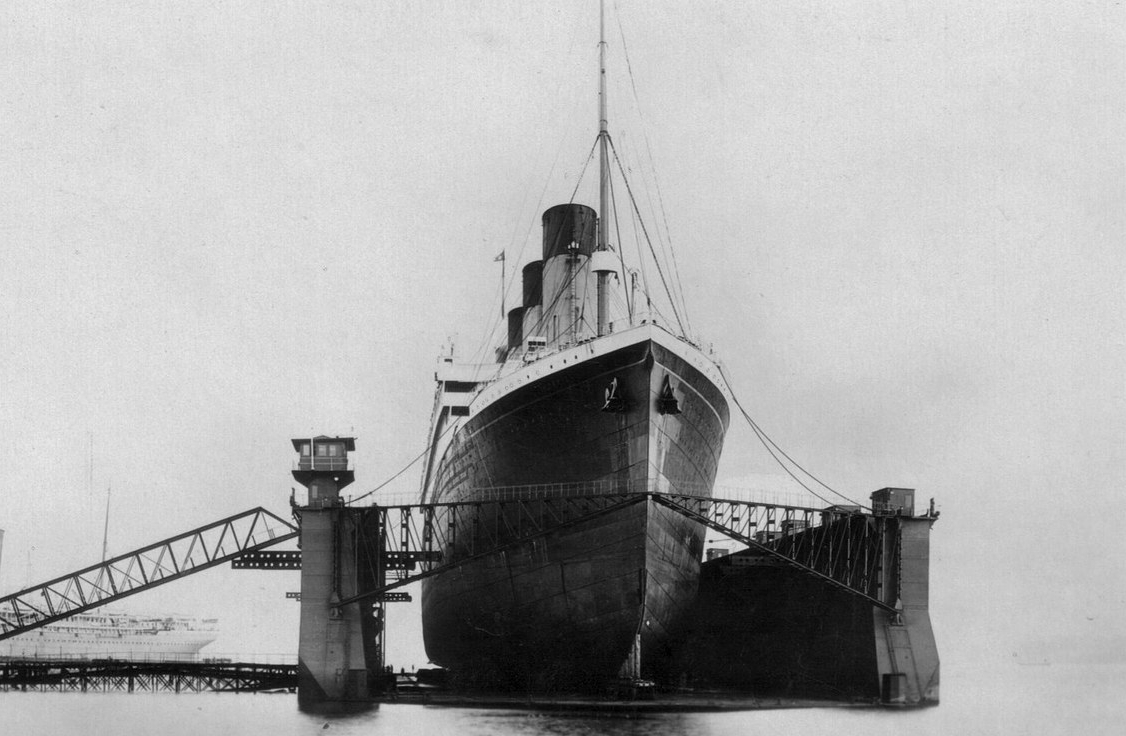

The Design

In many, if not most aspects, the Olympic and the Titanic were twins, if different in size. They had the same number of lifeboats and lifeboat setup, the same passenger facilities, fittings, deck designs, and technical specs—even a Grand Staircase nearly identical to that of the Titanic.

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

The First Class Experience

When it came to the experience that the Olympic offered first class passengers, the White Star Line truly spared no expense. Aside from the Grand Staircase, there were stately cabins, some of which even had private bathrooms, a large dining hall, and a smaller restaurant. On top of that, there was a smoking room, the Veranda Café, which was festooned with palm trees, a pool, a Turkish bath, a gym, and several other places where guests could eat or socialize.

John Bernard Walker, Wikimedia Commons

John Bernard Walker, Wikimedia Commons

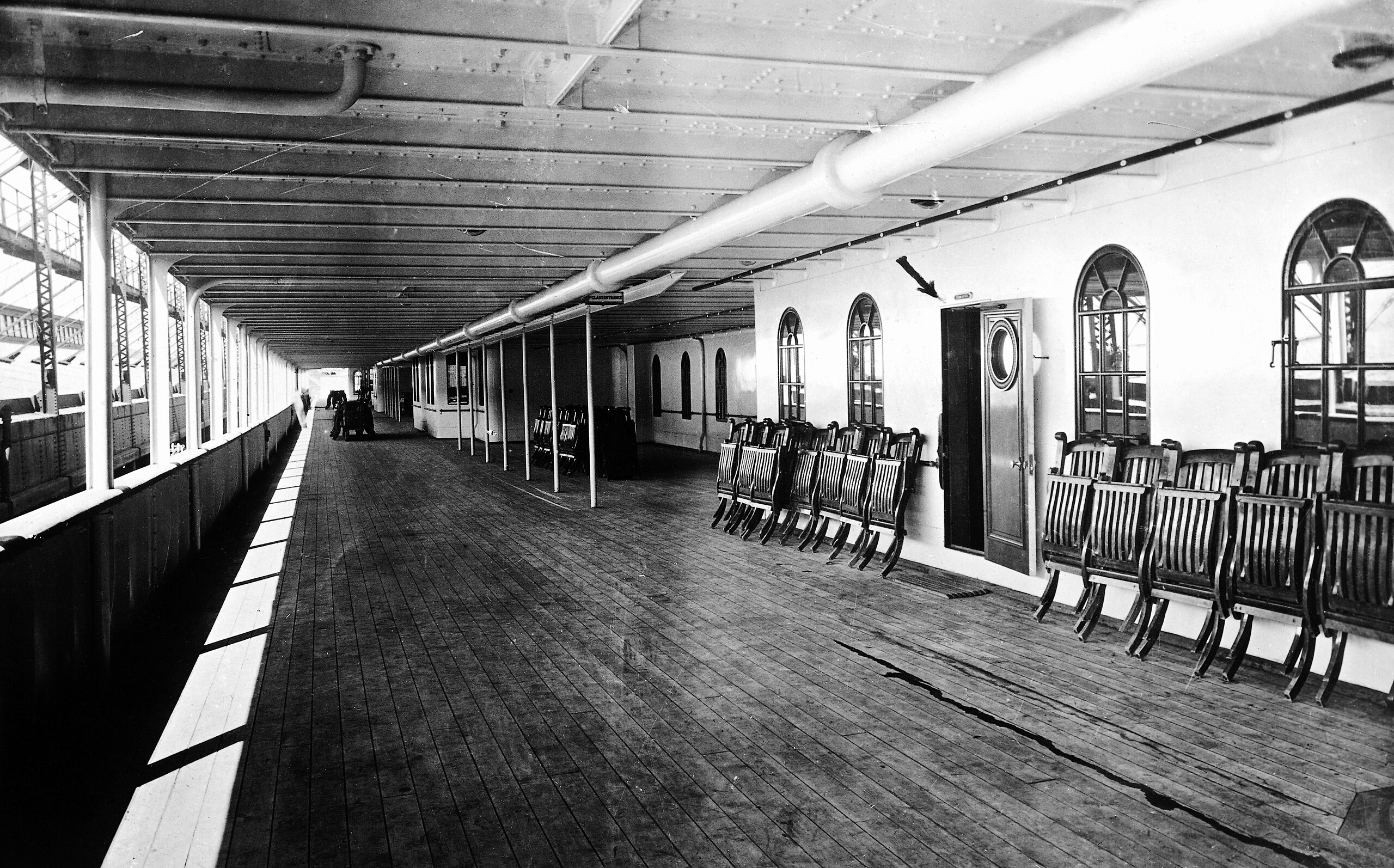

The Second Class Experience

Second class passengers had a fair amount of amenities to themselves as well, including a smoking room, a library, a large dining hall, and an elevator.

Bedford Lemere & Co, Wikimedia Commons

Bedford Lemere & Co, Wikimedia Commons

The Third Class Experience

Though the third class experience couldn’t compare to what passengers in first or second class had, they did enjoy a considerably more upscale voyage than what was offered on other ships. While other boats generally had large, open dorms for third class passengers, the Olympic offered cabins with between two and ten bunks.

Third class passengers also had a smoking area, restaurant, and common area of their own.

Bedford Lemere & Co, Wikimedia Commons

Bedford Lemere & Co, Wikimedia Commons

A Work In Progress

In some cases, lessons “learned” after the launch of the Olympic influenced the design of the Titanic and Britannic. One of these—the enclosure of Titanic’s B-deck—actually led to just over 1,000 tons of additional weight, one of the deciding factors which led to Titanic stealing the “world’s largest ship” title from the Olympic.

Francis Godolphin Osbourne Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Francis Godolphin Osbourne Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Double Trouble

After the Olympic completed its sea trials, White Star Line pulled off a clever publicity stunt—sending it on its voyage from Dublin to Liverpool, its port of registration, at the same time that it launched the Titanic. Then, the Olympic sailed to Southampton and a specially-built dock that accommodated its massive size, to get ready for its maiden voyage.

Robert John Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Robert John Welch, Wikimedia Commons

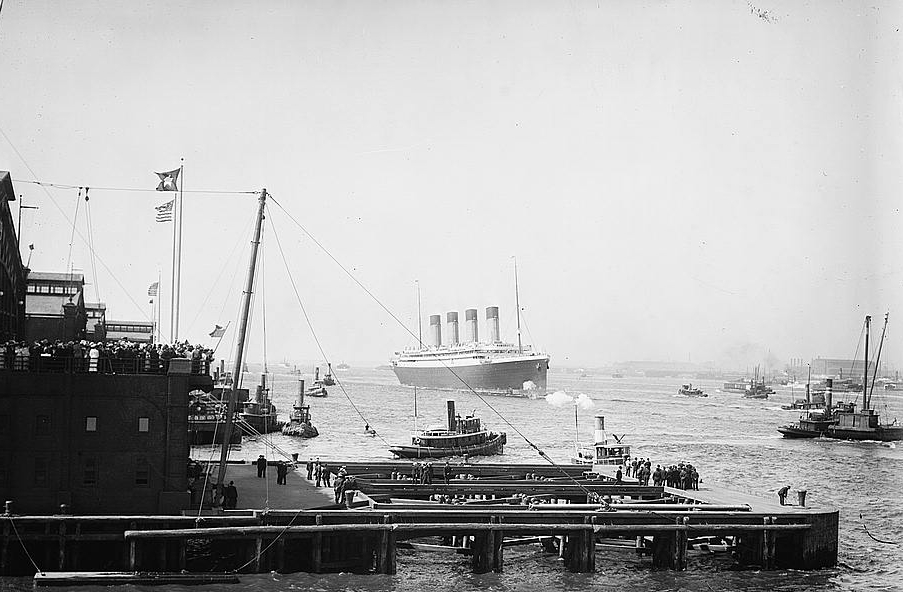

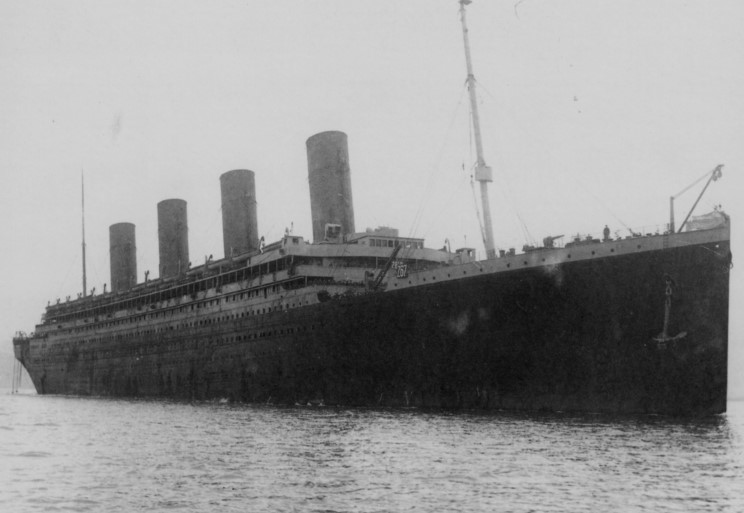

The Maiden Voyage

On June 14, 1911, the RMS Olympic took off from Southampton, England, and stopped at Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown, Ireland before crossing the Atlantic Ocean to New York City, where it arrived one week later, on June 21. On that maiden voyage, the Olympic carried 1,313 passengers. Also on board was the ship’s designer, Thomas Andrews, and a team of engineers from Harland and Wolff, there to address problems and opportunities for redesign on the fly.

Finally, at the helm was Edward Smith—a name familiar to many, as the same man who captained the Titanic.

New York Times, Wikimedia Commons

New York Times, Wikimedia Commons

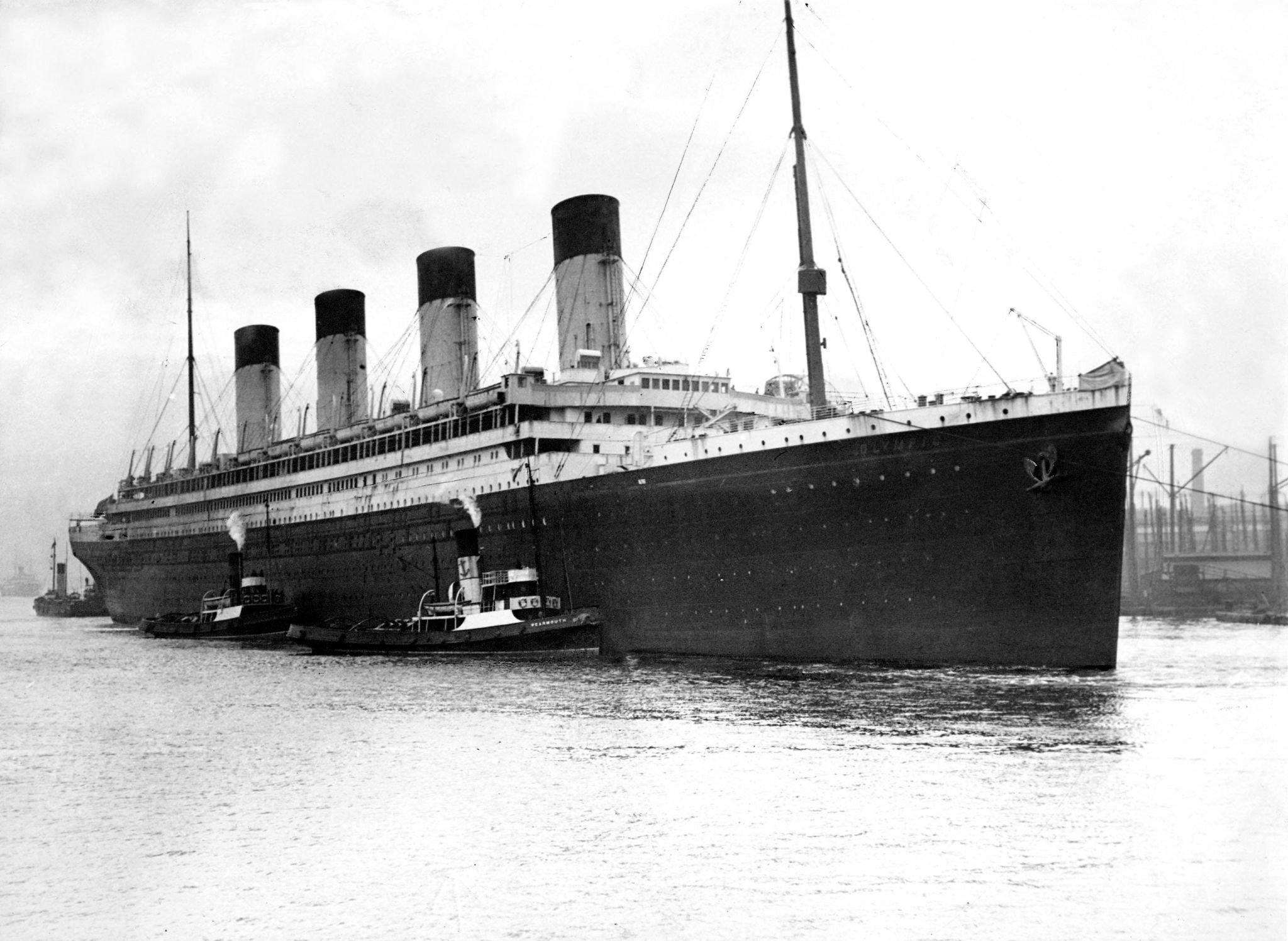

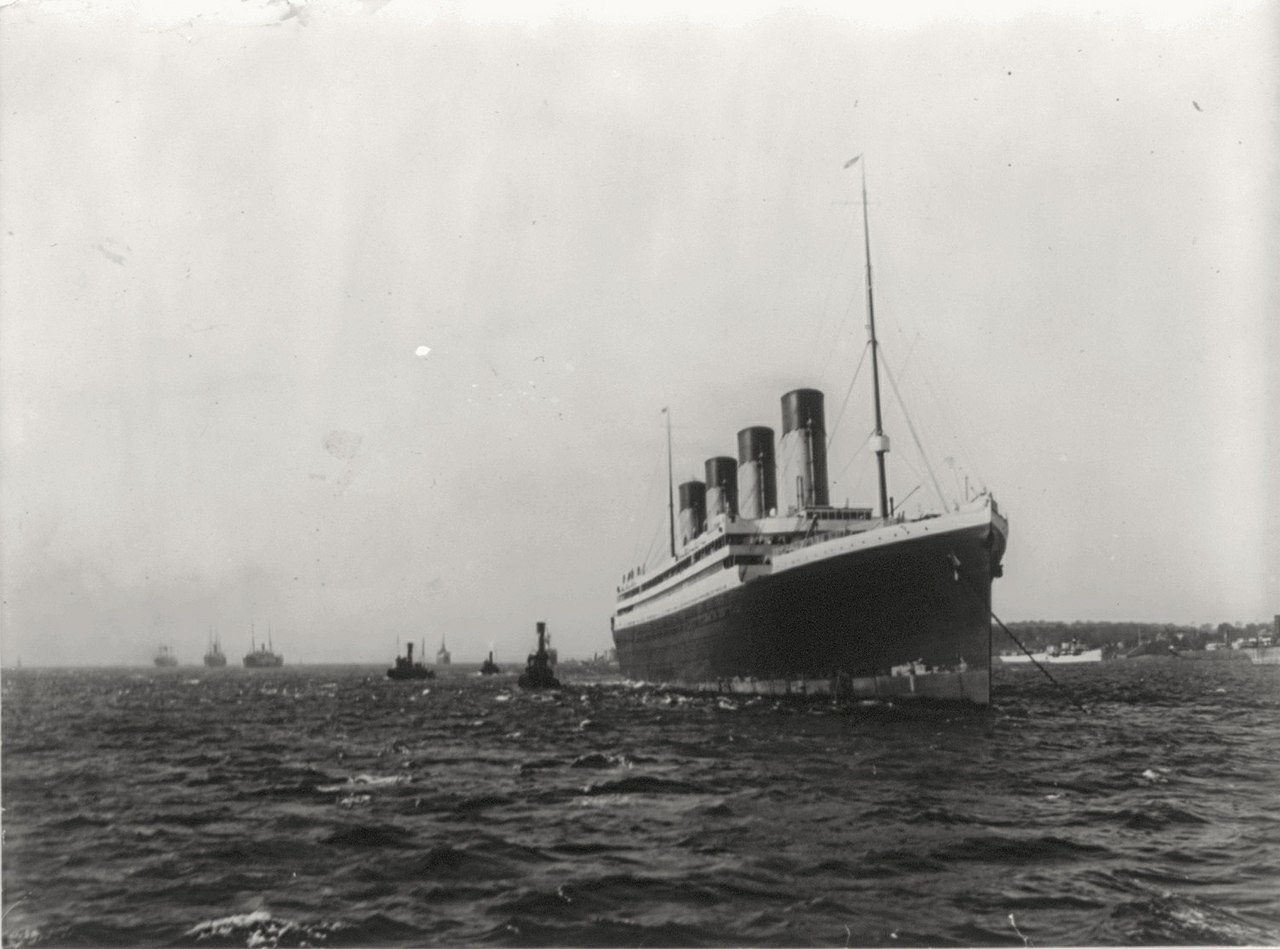

The Reception

Unsurprisingly, the “largest ship in the world,” the Olympic, got a lot of press on its maiden voyage. It was greeted in NYC by scores of visitors, and when it was open to the public, some 8,000 people explored its corridors and decks, with 10,000 gathering to watch it make its return to England—a trip nearly double in size, with 2,301 passengers.

Paul Thompson, Wikimedia Commons

Paul Thompson, Wikimedia Commons

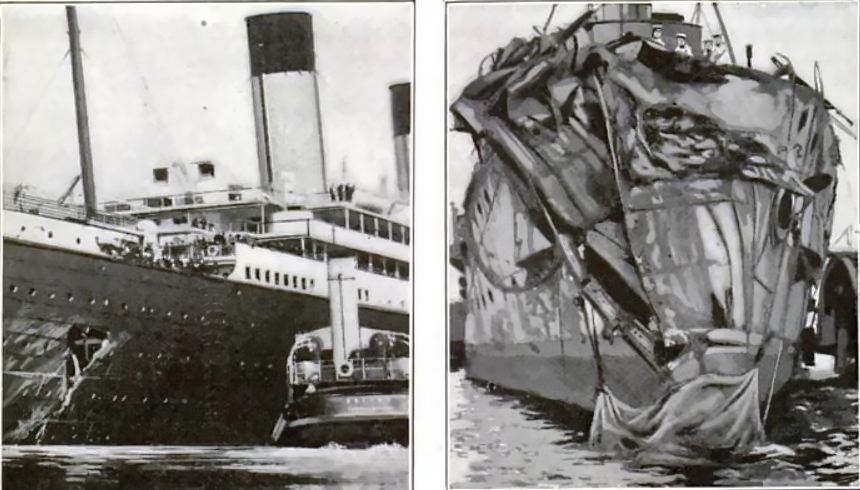

The First Incident

The Olympic had been on a scant four journeys when, on its fifth, it ran into its first big disaster—quite literally. On September 20, 1911, with Captain Edward Smith at the helm, the Olympic collided with a British warship, the HMS Hawke, on a strait that runs between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain.

Symonds & Co, Wikimedia Commons

Symonds & Co, Wikimedia Commons

Hawke Vs Olympic

The ships were sailing parallel to each other when the Olympic went to turn starboard, resulting in the nose of the Hawke, which was outfitted to ram other ships, hitting the side of the Olympic. It left massive holes above and below the waterline of the Olympic—though the ship was still able to sail to safety in Southampton.

The Hawke wasn’t so lucky.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Surveying The Damage

In photos, the severity of the damage to the Hawke against the damage to the Olympic is quite notable. The ship almost capsized in the incident, but in an incredible twist of fate, there were no serious injuries or deaths that resulted from the collision. Both ships, in the end, were repaired—but there were serious consequences to it all.

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

The Inquiry

There was one question when it came to the collision of the Olympic and the Hawke—who was at fault? The Royal Navy made a compelling case, claiming that the massive size of the Olympic created a displacement when it turned, which had essentially pulled the Hawke into its side.

The Solent

The Solent is the name of the strait between the Isle of Wight and Great Britain where the incident took place, and liners going through it would often transfer responsibility to a harbor master, who guides ships through tight or highly-trafficked waterways. Though, at the time of the accident, it was the harbor master who had been in charge of the Olympic, it was White Star Lines—and by extension, the Titanic—who paid the price.

The Consequences

In the aftermath of the incident, White Star Lines not only had to cover extensive legal bills, it also had to pull resources from the construction of the Titanic to quickly repair the Olympic and make it ocean-ready again—and profitable—again. Parts had to be pulled off the Titanic and used in the repairs of the Olympic, pushing back the Titanic’s maiden voyage by weeks.

SandyShores03, Wikimedia Commons

SandyShores03, Wikimedia Commons

There’s No Such Thing As Bad Publicity

There was one unforeseen side effect of the whole collision, though. Instead of damaging White Star Line’s reputation, the fact that the Olympic survived the whole accident relatively unscathed left an impression on people—one that the Line’s Olympic-class of ships might just be “unsinkable”.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Crew Change

As Harland and Wolff put the finishing touches on the Titanic, White Star Lines called on Edward Smith to captain it. He’d helmed the maiden voyages of their newest ships since 1904, and this would be no different. For his replacement on the Olympic, they tapped Herbert James Haddock, who had actually been the first person to captain the Titanic as it sat in Belfast in the last week of March, 1912.

With this captain swap completed, the Titanic was ready for its maiden voyage—just as the Olympic was returning from New York.

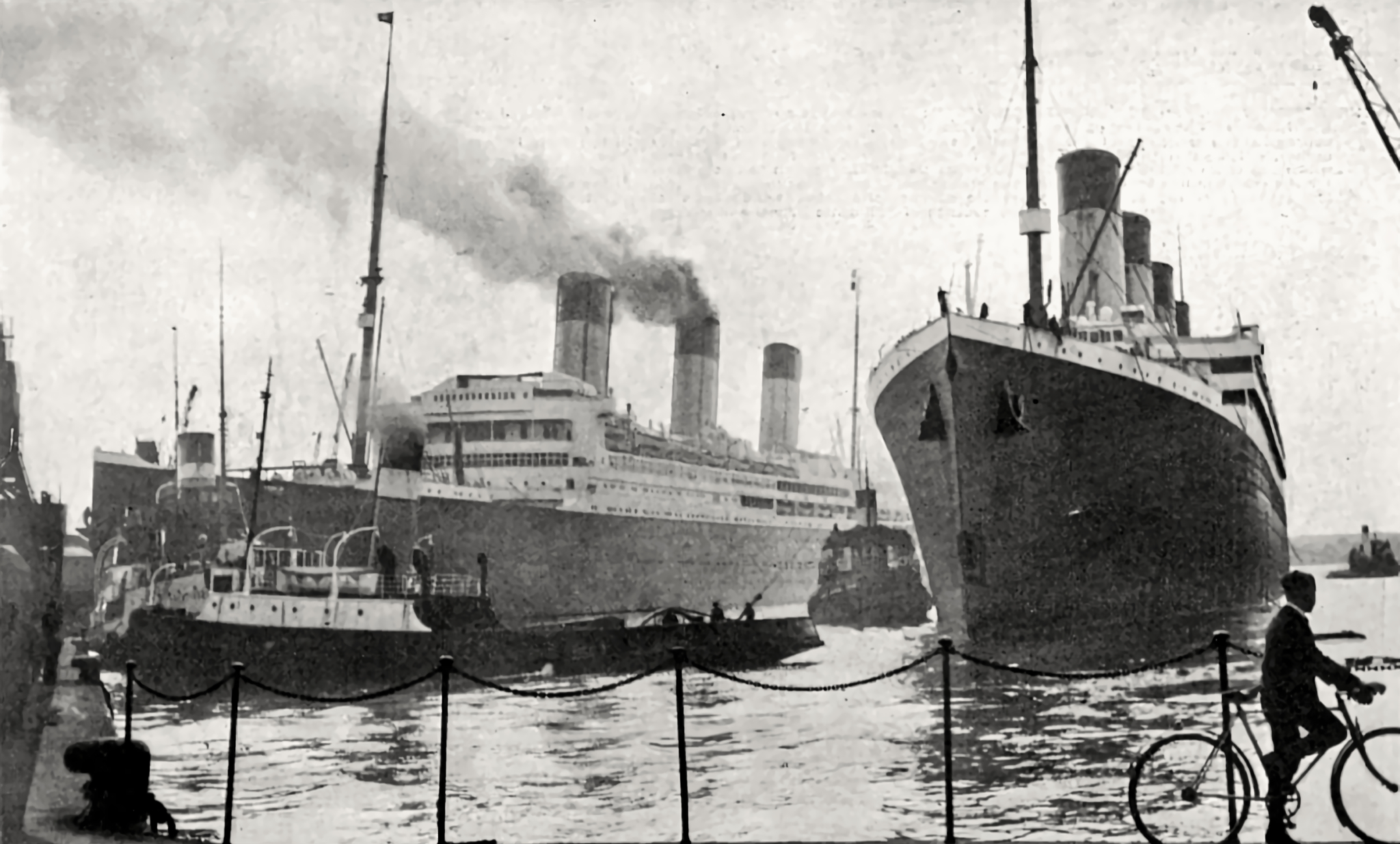

The Distress Call

Just after midnight on April 15, 1912, the Titanic sent out its first distress call. A wireless operator aboard the Olympic heard the call and immediately alerted Captain Haddock, who changed the Olympic’s course to head to its sister ship. It had just over 500 miles to cross.

Tom, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Tom, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

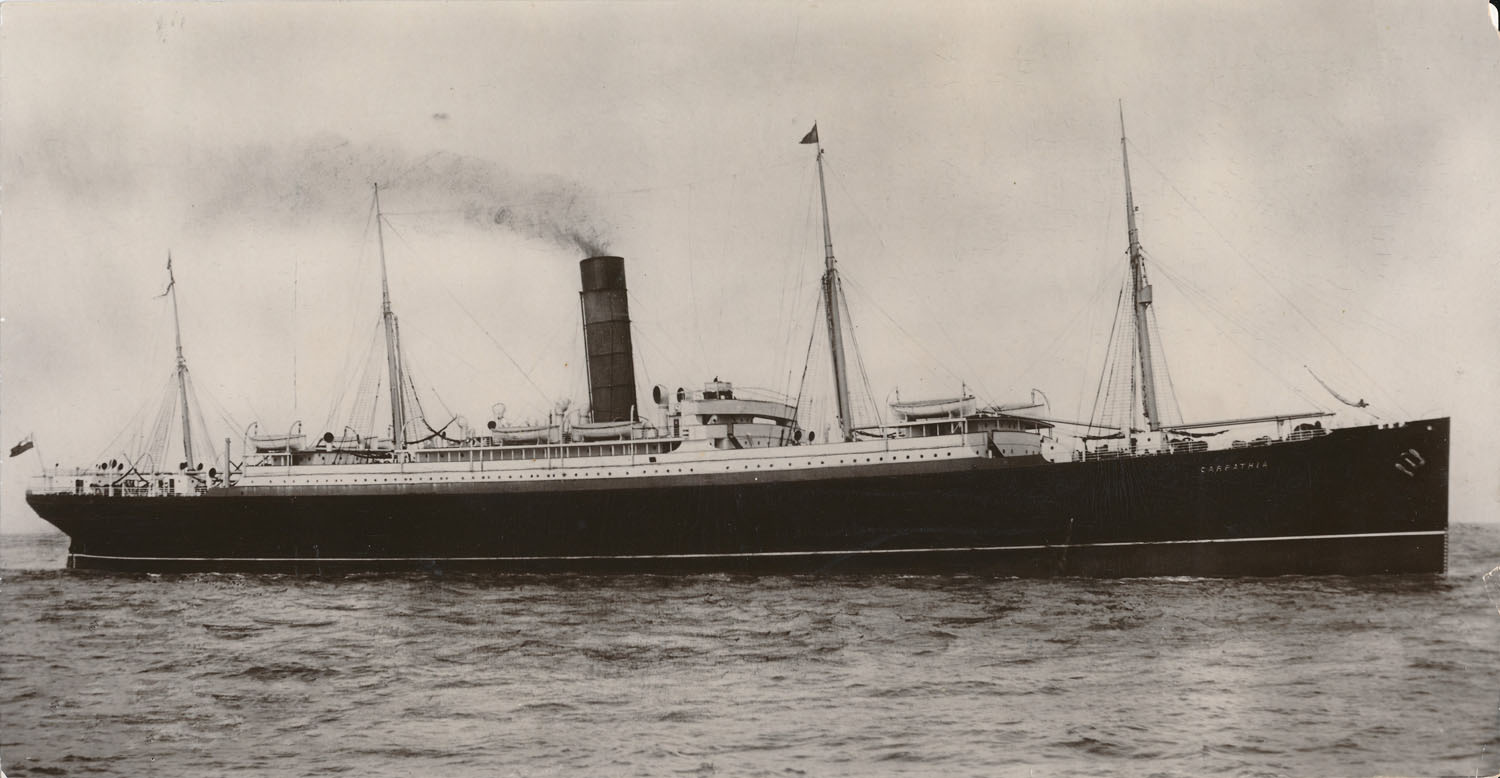

Too Little, Too Late

The Olympic had made it most of the way when they received a call from White Star Line’s major competition, Cunard’s RMS Carpathia. The ship’s captain said that it was too late for them to offer any help, and that the Carpathia had accounted for every lifeboat, saving 675 people.

Of course, this was only a fraction of the total people on board. Among those who perished were the Olympic’s one-time captain, Edward Smith, and the man who’d designed both the Olympic and the Titanic, Thomas Andrews.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

(Un)Welcome Aboard

Still, the Olympic wanted to help, so they contacted the Carpathia, offering to help transport survivors. However, that’s when bureaucracy got in the way. The chairman of the White Star Line told the captain of the Carpathia to refuse the offer. He thought that bringing survivors on board a nearly-identical boat would be frightening.

With that, the Olympic continued its voyage back to Southampton—likely a tense and upsetting six days for the passengers on board.

Fred Pansing, Wikimedia Commons

Fred Pansing, Wikimedia Commons

The Investigation

Though the Olympic hadn’t been able to help the Titanic directly, it played a major role during the inquiry into the latter ship’s sinking that followed. As they were nearly identical, the Olympic was used by investigators and thoroughly examined—a process which included sea trials to gauge both ships’ turning speeds.

However, these very similarities were about to present a new set of problems for White Star Line and the Olympic.

Harland & Wolff Shipyard, Wikimedia Commons

Harland & Wolff Shipyard, Wikimedia Commons

The Lifeboat Problem

When the Titanic went down, over 1,500 people perished, including approximately 688 crew members. This was in part due to the fact that there were more people on board than there were lifeboats. And, as both ships had nearly identical lifeboat set-ups, the crew of the Olympic became acutely aware of these problems as the news of the Titanic broke and outlets began to report on the discrepancy.

Having seen just what kind of danger this presented, the crew of the Olympic wasn’t about to take it sitting down.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Strike

Though the Olympic had immediately been outfitted with collapsible lifeboats when it returned to Southampton after its attempted rescue of the Titanic, a number of the crew didn’t trust their seaworthiness. In late April 1912, 284 of the Olympic’s firemen went on strike. And they had good reason, too.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

A Disaster Waiting To Happen

Upon examining the lifeboats, which had been transferred from troopships, crew members made a disturbing discovery. Many had rotted to the point where they wouldn’t open up. They asked for wooden lifeboats, but White Star Line refused. They even claimed the collapsible boats had passed inspection.

Sobered by the massive loss of life from the Titanic, many of the Olympic’s crew weren’t willing to put their lives on the line for their job.

Jay Henry Mowbray, Wikimedia Commons

Jay Henry Mowbray, Wikimedia Commons

Stokers On Strike

With a departure impending, the White Star Line scrambled to bring on scabs, hiring 100 workers locally and going as far as Liverpool to find more. At the same time, a group of the striking stokers attended a test of four of the collapsible lifeboats. One was found to be faulty, and those present said they would recommend a return to work if it was replaced.

There was just one problem.

Library of Congress, Getty Images

Library of Congress, Getty Images

Which Side Are You On?

The focus shifted from the faulty lifeboats to the non-union scabs that White Star Line had brought on to stick to their departure date. Union laborers on the ship claimed that the scabs were unqualified and therefore dangerous to work with. They asked White Star Line to dismiss them. It was a request that the company refused.

As a result, 54 of the sailors on board prepared to leave the ship—though there was an unexpected surprise waiting on shore.

Mutiny On The Olympic

When the 54 sailors who walked off the Olympic arrived on shore, they were greeted by waiting authorities, eager to detain them on charges of mutiny. Now, they would have to fight the charges in court. 10 days later, officials in Portsmouth found that the charges were valid, but refused to imprison or fine the 54 sailors, due to the unusual circumstances.

The White Star Line knew that they had a PR nightmare on their hands, so they quietly let the sailors return to work and planned their next steps to restore their name.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Trial And Error

Less than six months after the sinking of the Titanic, White Star Lines brought its sister ship, the Olympic, back to its birthplace—the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast, Ireland. They wanted to solve the problems they’d uncovered in the Titanic investigation and in the Olympic’s previous six months of service, and improve safety measures.

After the workers’ strike of 1912, they knew exactly where to start.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Lessons Learned

Harland and Wolff upped the number of lifeboats on the Olympic from 20 to 68, with supports for them to match. In the boiler and engine rooms, an extra watertight layer was added, essentially making it a double hull. Among many other improvements, more watertight bulkheads were added—on the Titanic, they had only gone up a short distance higher than the waterline, which had been one of the fatal flaws.

All these extra measures meant that the Olympic was guaranteed to survive in the same circumstances that had sunk the Titanic.

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

A Step Up

Rowland and Wolff didn’t just take care of safety measures during their retrofit of the Olympia. They also gave it a facelift, adding more luxury amenities for first class passengers, including more private bathrooms and more dining options. All in all, the makeover took nearly six months—and added so much additional weight that the Olympic once again took the title of “the largest ship in the world”.

William H. Rau, Wikimedia Commons

William H. Rau, Wikimedia Commons

Back In The Game Again

Ads from the White Star Line lauded the “new” Olympic and touted its new safety features in the wake of the sinking of the Titanic. Aside from a bad storm that resulted in some broken windows, it enjoyed a relatively peaceful stint as a passenger ship throughout 1913 and part of 1914—but disaster was once again lurking on the horizon.

Harland & Wolff, Wikimedia Commons

Harland & Wolff, Wikimedia Commons

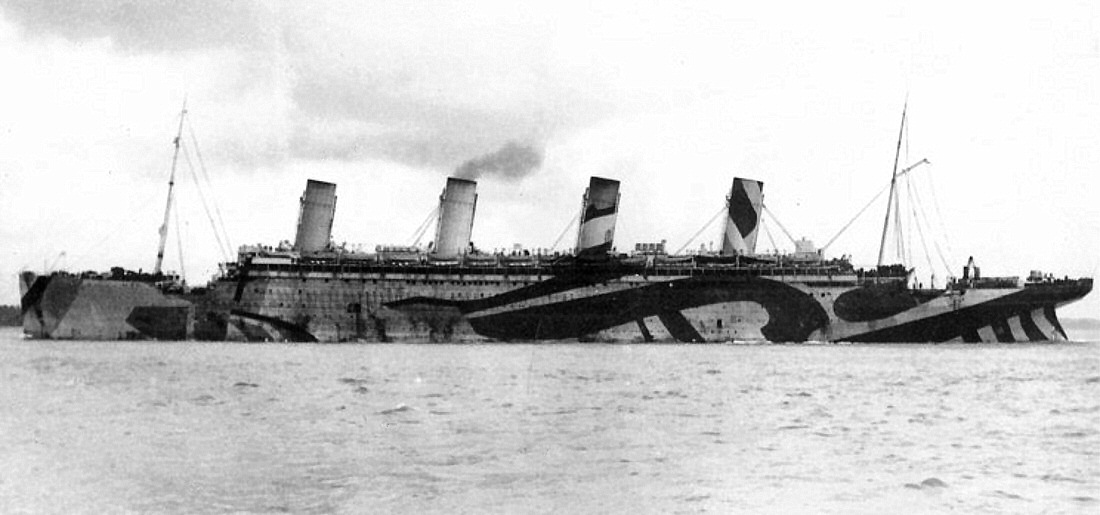

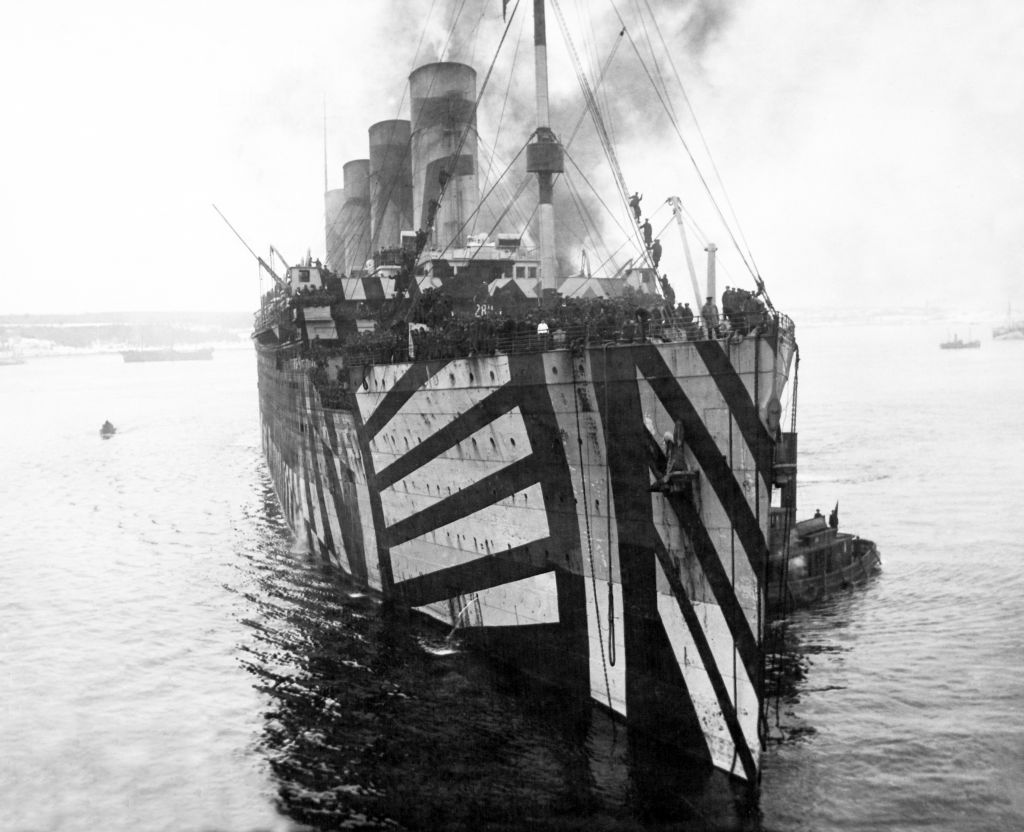

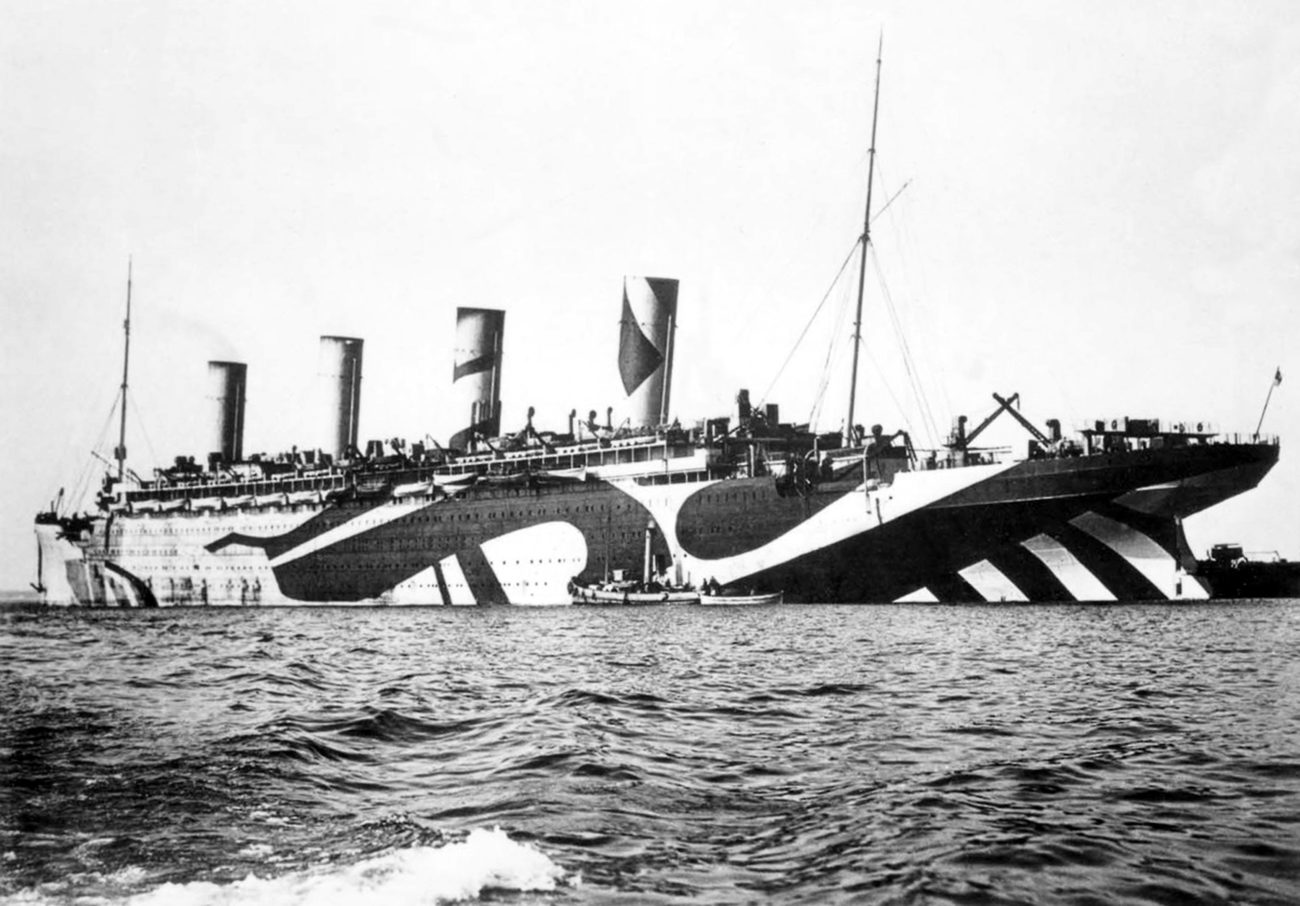

Going Undercover

When Britain joined WWI, the Olympic remained a passenger ship, though White Star Line had to take measures to camouflage it from German forces. These efforts included painting the ship grey, covering portholes, and keeping lights low or off. Many of the passengers at this time were Americans who had been visiting Europe when the conflict broke out, and were hoping to return to New York.

But still, fewer and fewer passengers were willing to step foot on the Olympic. And this time, it wasn’t due to bad publicity.

MaritimeQuest, Wikimedia Commons

MaritimeQuest, Wikimedia Commons

Early Retirement

The memory of the Titanic had quickly faded from view—but the threat from German U-boats had grown exponentially. White Star Lines prepared to close up shop, as it were, and take the Olympic out of commercial service temporarily. However, on its “final” voyage, it ran into trouble.

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Welch, Wikimedia Commons

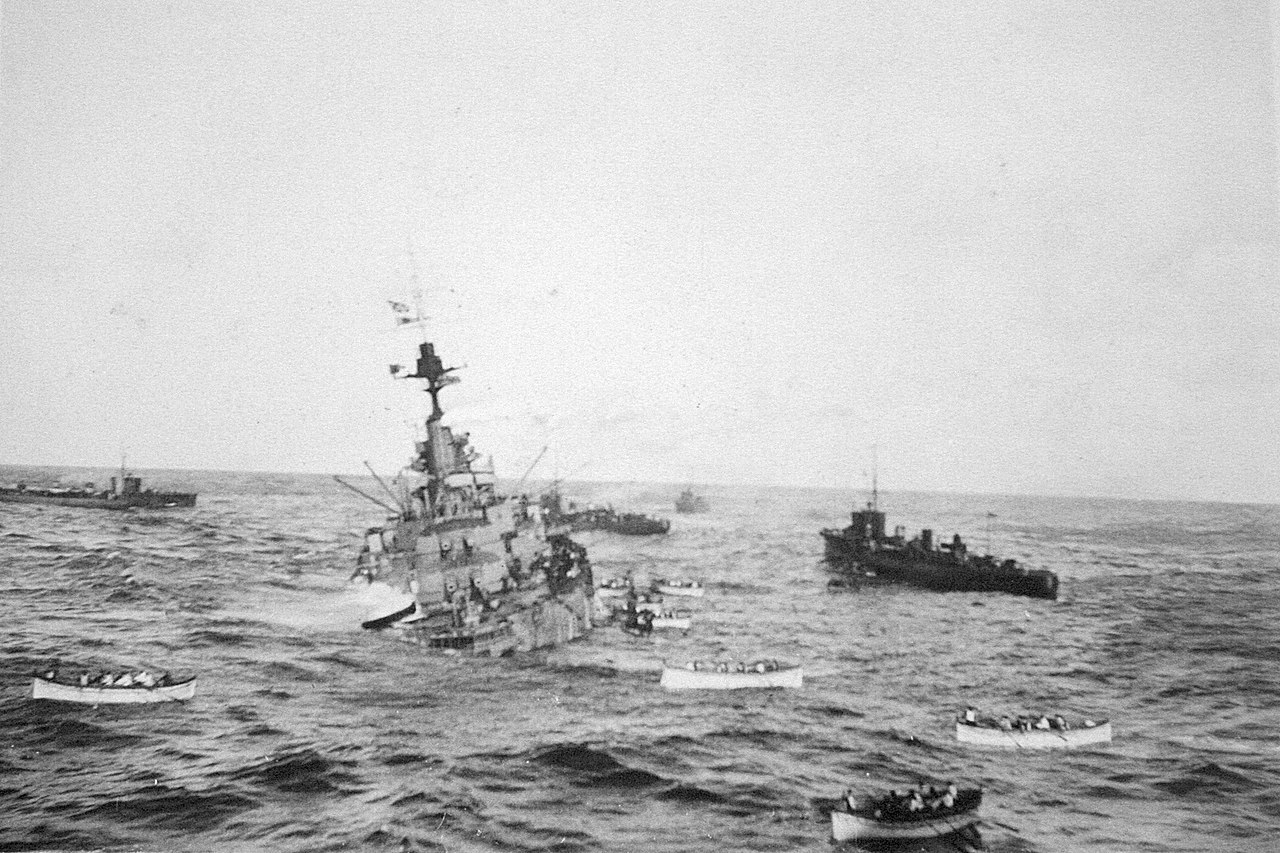

The Audacious Incident

On October 27, 1914, the Olympic received a distress call from the HMS Audacious. The battleship had hit a mine and was taking on water near Tory Island in Ireland. Finally, they had a chance to help where they hadn’t been able to during the Titanic disaster. 250 of the Audacious crew took shelter on board the Olympic as two other nearby ships struggled to save the battleship.

Sadly, their efforts were futile. As it became clear the ship was going to go under, the rest of the crew evacuated to the Olympic and another waiting ship. It was a massive loss for Great Britain and the Allies—and the Olympic was caught in the middle.

Edith and Mabel Smith , CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Edith and Mabel Smith , CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Top Secret

The Commander of the Home Fleet, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, knew that the sinking of the Audacious would be a major blow to the public’s morale, only a few months into Great Britain’s involvement in WWI. When the Olympic, carrying its passengers and survivors of the Audacious, arrived at Lough Swilly in Ireland, only the Audacious crew was allowed to disembark.

The passengers were held on board and communications were stopped. They were now at the mercy of Jellicoe’s plan to keep the sinking of the Audacious secret. All in all, they were held for five days before they were allowed to disembark in Belfast.

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

The Best-Laid Plans

After the final commercial voyage, White Star Lines planned to have the Olympic returned to Belfast to wait out the war. In the same shipyard, the Britannic, its other sister ship, was waiting for the war to end so it could be completed and take its maiden voyage. Of course, though, this was a war—a fierce one, and England had a shortage of ships.

Allan C. Green, Wikimedia Commons

Allan C. Green, Wikimedia Commons

Another Makeover

In May of 1915, the Olympic was requisitioned by the Admiralty to act as troop transport in WWI. The Britannic, which still wasn’t finished yet, was requisitioned as a hospital ship. All of a sudden, White Star Lines were in the war business. In four months, the Olympic was fitted with equipment to convert it to a troop ship, with a capacity of 6,000. In September, it participated in its first campaign, carrying troops to Greece to fight in the Battle of Gallipoli.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Courage Under Fire

Though the Olympic’s speed had never been its strength, in the fight against German U-boats, it now actually put them at an advantage—however, it was also a large target. This caused a controversy when the wartime captain of the Olympic stopped to save 34 survivors of the French ship Provincia. The British Admiralty claimed he’d put the ship in danger—while the French gave him a Gold Medal of Honour. You can’t please everyone!

Arthur Lismer, Wikimedia Commons

Arthur Lismer, Wikimedia Commons

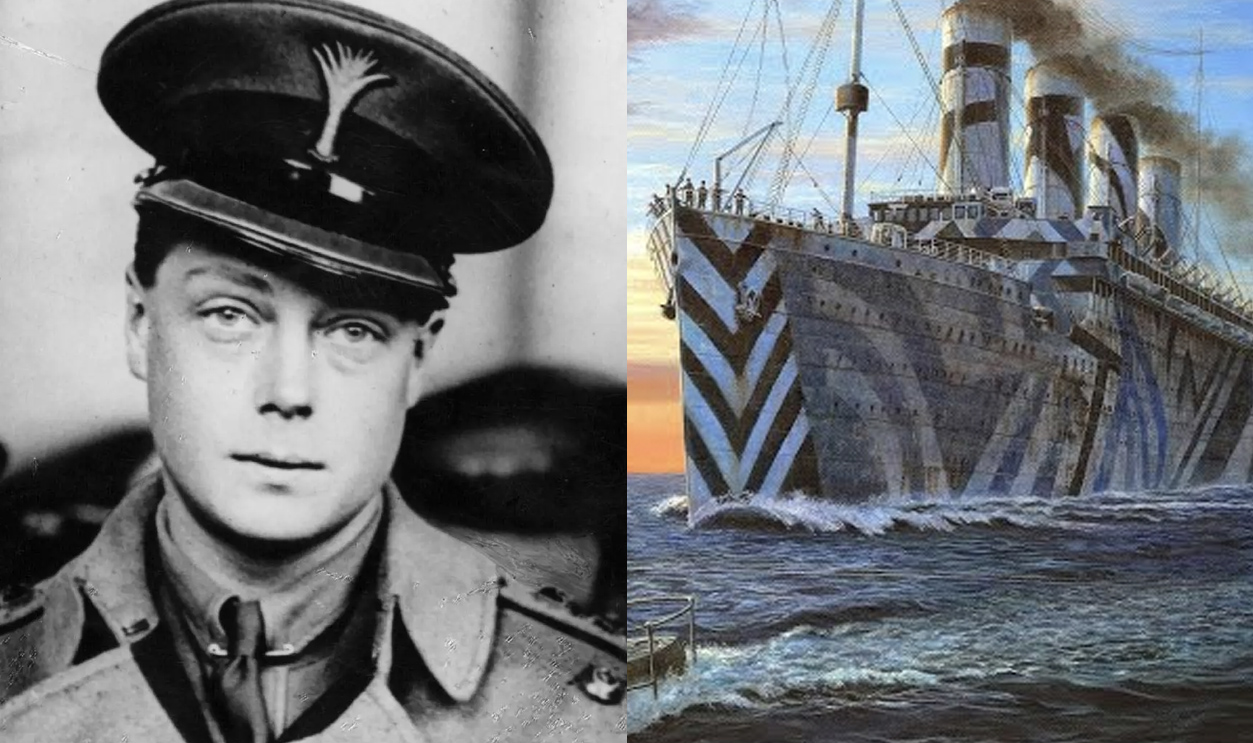

Give ‘Em The Old Razzle Dazzle

The Olympia’s size was both a source of strength and a disadvantage during wartime, and for a while, she was deemed unsuitable to participate in more decisive missions. The Olympia spent several months transporting troops in battle camouflage going between Great Britain and Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, where she became a beloved image in the city.

The thing is? The Olympic still had one big battle in her.

Pictures from History, Getty Images

Pictures from History, Getty Images

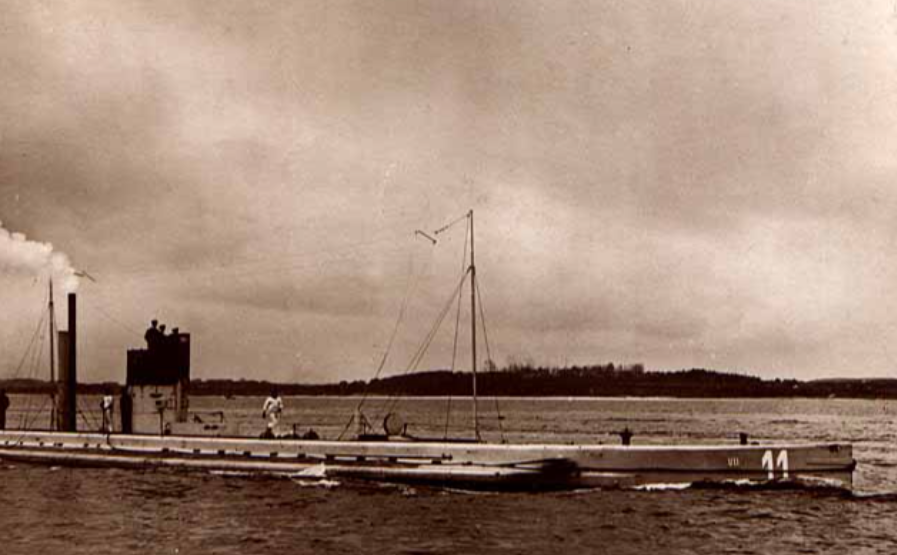

The Sinking Of U-103

When the US joined WWI, the Olympic began transporting American troops as well. It was on one of these voyages, in May of 1918, that the crew of the Olympic spotted U-103, a German U-boat, a scant 1,600 feet in front of them. They opened fire immediately and also rammed the craft, causing it to sink. They did all this knowing they were in danger—but not knowing how dire it was.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

A Narrow Escape

Later, it was discovered that U-103 had been about to fire on Olympic, but hadn’t been able to flood two of the torpedo tubes in time. The Olympic had saved itself and the men it was carrying with just seconds to spare. Its wartime captain, Bertram Fox Hayes, was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, a great honor—and some of the American troops on board also created a plaque for the ship to show their gratitude.

It was the only passenger liner to both ram and sink a German U-boat in WWI.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Old Reliable

Thanks to its prolonged, prolific service in WWI—carrying some 201,000 men over 184,000 miles over those years—the Olympic was given the name “Old Reliable”. Sadly, that reputation could not be shared with its other sister ship, the Britannic, which hit a naval mine and sank in Greece in 1916. It was the largest ship lost in WWI.

After that, the Olympic was the only surviving Olympic-class ship in the White Star Line.

William H. Rau, Wikimedia Commons

William H. Rau, Wikimedia Commons

Back In The Saddle Again

Following the end of WWI, the Olympic once again returned to dry dock in Belfast to be retrofitted to become a passenger liner again. During the process, engineers found evidence that it had been involved in another dire near-miss, likely from an unexploded torpedo fired by a U-boat just months after the U-103 incident.

The Olympic was ready to take on passengers again by June 1920—and the demand was high.

Salad Days

In 1921, the Olympic smashed its previous records for passengers, transporting 38,000 people. It was the best year of the ship’s career. Throughout the decade, the ship was a popular choice for the rich and famous, and notable passengers include Marie Curie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, and the future Edward VIII, then Prince of Wales.

In fact, the Olympic was the ship that first brought Cary Grant, then a fledgling actor, to the US. Sadly, the good times couldn’t last forever.

The Times Were Changing

Changing immigration laws in the US reduced the demand for transatlantic travel, at least in the third class. Though White Star tried to shift with the currents, making improvements and doing their best to attract travelers, there was one factor that they simply couldn’t fight: The Great Depression.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

A Never Ending Battle

White Star Lines found it hard to keep the Olympic moving and profitable in the wake of the Great Depression. Passengers were dwindling, and efforts to upgrade the boat were met with apathy. In 1933 and 1934, the Olympic operated at a net loss for the very first time. Then, in 1934, disaster struck yet again.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Nantucket Lightship Collision

In May of 1934, the Olympic failed to make a turn and accidentally sliced through the Nantucket Lightship LV-117. The smaller boat sank nearly immediately. Though the Olympic acted fast to lower lifeboats to survivors, there were seven casualties out of 11 crew.

US Coast Guard, Wikimedia Commons

US Coast Guard, Wikimedia Commons

The Writing On The Wall

Soon after, White Star Lines and Cunard merged, in order to finance the building of two new liners to take over express service. With the completion of the ships, the Olympic was basically made redundant. Cunard White Star retired the Olympic in 1935. Though a few potential buyers showed interest, only one came through—a Member of Parliament who bought it so its demolition could be a literal make-work project for a depressed town in England.

The End Of The Olympic

It was a sad and undignified end for the craft that had survived so much and earned the nickname “Old Reliable” in battle. As the ship’s former engineer said, "I could understand the necessity if the 'Old Lady' had lost her efficiency, but the engines are as sound as they ever were".

Over the years, the Olympic had transported 430,000 passengers over 1.8 million miles, completing 257 round trips across the Atlantic Ocean. But there’s also an even darker side to its remarkable career.

What If?

Unlike its sister ships, the Titanic and the Britannic, the Olympic didn’t sink. However, if the Olympic hadn’t collided with the HMS Hawke in 1911, pushing back the completion of the Titanic, things might have been different.

It’s incredibly likely that the same drifting ice that destroyed the Titanic would not have been in its course if it had left on March 20, 1912, as planned. But then, what would’ve happened to the troops that the Olympic saved during WWI? When it comes to the White Star Line’s Olympic-class liners, it’s a game of historical “what if”.

William H. Rau, Wikimedia Commons

William H. Rau, Wikimedia Commons