When The Past Finally Clears Its Throat

For a long time, the world’s first recorded pandemic has been one of those historical stories that sounds obvious—until you ask the annoying question: “Okay, but what actually caused it”. People have argued about the culprit for centuries, mostly because the sixth century didn’t exactly come with lab reports. Now researchers have managed to pull a real answer out of ancient remains, which is both incredible and a little spooky in the best way.

The Pandemic That Kicked Off A Grim Tradition

Back in the 500s, an outbreak swept through the Eastern Roman world and left a trail of chaos behind it. Whole communities were hit hard, trade and government were disrupted, and the ripple effects didn’t politely stop at the city limits. It’s often treated like the opening act for later disasters, but on its own, it was a massive historical gut punch.

The Big Question People Kept Arguing About

Historians had descriptions, and some of them were detailed enough to make you wince. But descriptions are still just descriptions, and lots of diseases can look similar when you’re watching people get sick in real time. For generations, the debate bounced around between possibilities, because no one could point to a specific microbe and say, “It was you”.

Why It Stayed A Mystery For So Long

The simple problem was evidence. The people who lived through it didn’t have microscopes, DNA sequencing, or even the concept of bacteria as a thing. So the story lived in texts and secondhand accounts, which meant later scholars were always working from clues, not proof. The missing piece was physical confirmation, and that’s exactly what this new work delivered.

iris marie kelly , Wikimedia Commons

iris marie kelly , Wikimedia Commons

The Modern Trick: Ancient DNA

Here’s the clever part: human remains can preserve genetic traces for a very long time, especially in certain places in the body. Researchers can extract tiny fragments of DNA and check whether any pathogens show up in the samples. It’s like a forensic investigation, except the crime scene is 1,500 years old and everyone involved has been gone since before anyone thought plumbing was optional.

The Name That Pops Up: Yersinia Pestis

The bacterium they identified was Yersinia pestis, the same one tied to later plague outbreaks. That’s a huge deal because it means the long-suspected explanation is now backed by genetic evidence. Not “this seems likely,” not “the symptoms kind of match,” but a direct link. It turns a historical theory into a confirmed answer.

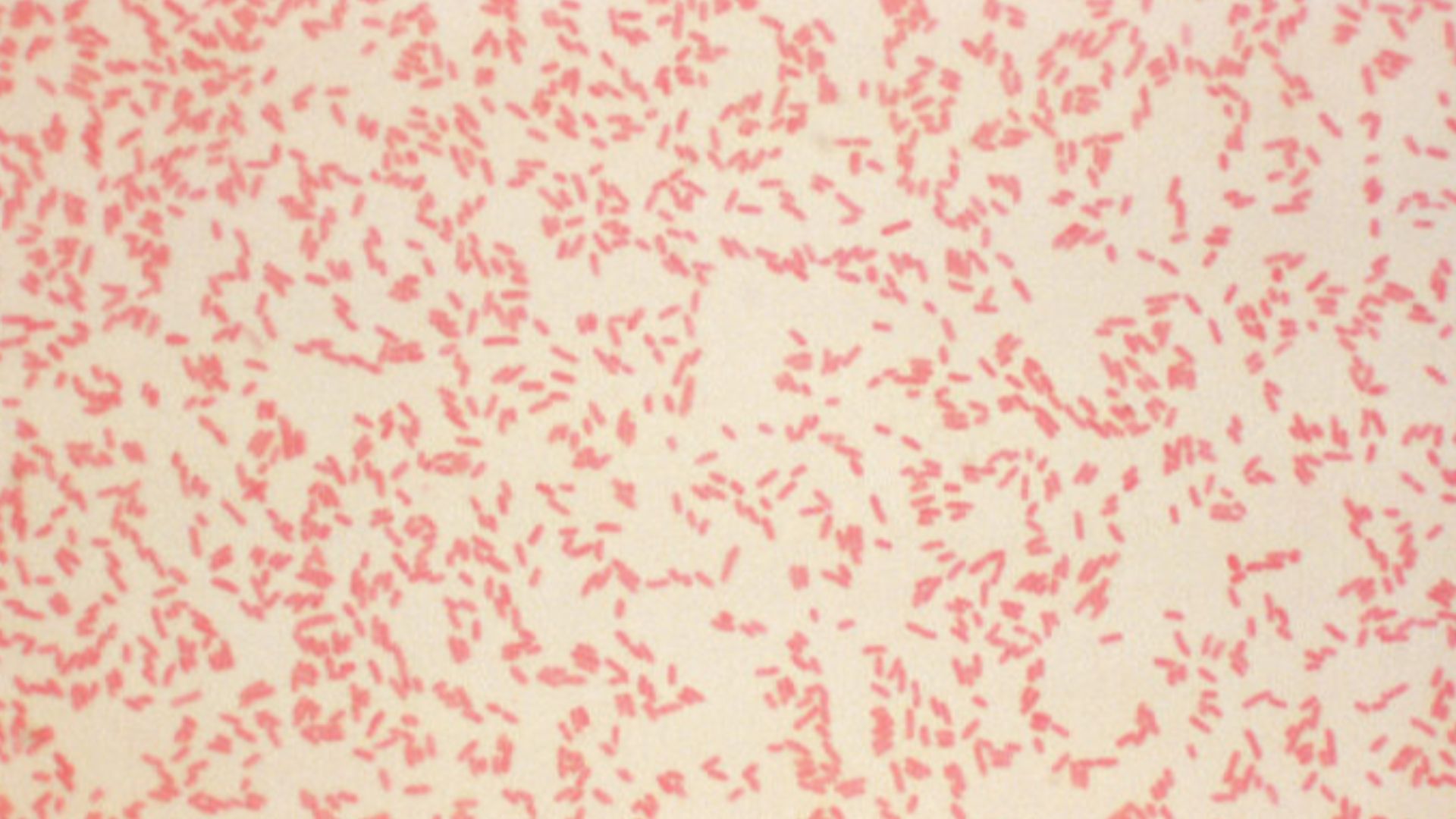

U.S. Center for Disease Control, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Center for Disease Control, Wikimedia Commons

Why Confirming It Changes The Whole Story

Plenty of people suspected plague was responsible, but “suspected” has a way of keeping arguments alive forever. Once you have genetic evidence, the conversation shifts from “maybe” to “okay, now what does this tell us”. It also means the plague’s history as a major human wrecking ball goes back further than we could prove before. That’s not a comforting thought, but it’s a useful one.

Teeth: The Unexpected MVP

If you’re wondering how scientists even get usable DNA from remains this old, teeth are a big part of the answer. Teeth protect material inside them, and that can include traces of pathogens circulating in the bloodstream when someone passed. It’s not glamorous, but it’s effective. Ancient teeth are basically little locked safes of information.

The Site That Helped Crack The Case

The remains came from a location tied to an ancient urban center, the kind of place where people lived close together and life moved fast. Dense populations plus constant movement is basically the dream scenario for a contagious disease. If you’re trying to understand how an outbreak got traction, that kind of setting matters. It’s the difference between a spark and a wildfire.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

What A Mass Burial Suggests

When you find a lot of people buried together, it often points to a crisis that didn’t leave much time for normal rituals. It’s the archaeological version of a giant flashing warning light. It suggests the community was overwhelmed, trying to respond quickly, and probably scared out of its mind. Combine that with pathogen evidence, and it’s hard not to imagine how intense those weeks or months must have been.

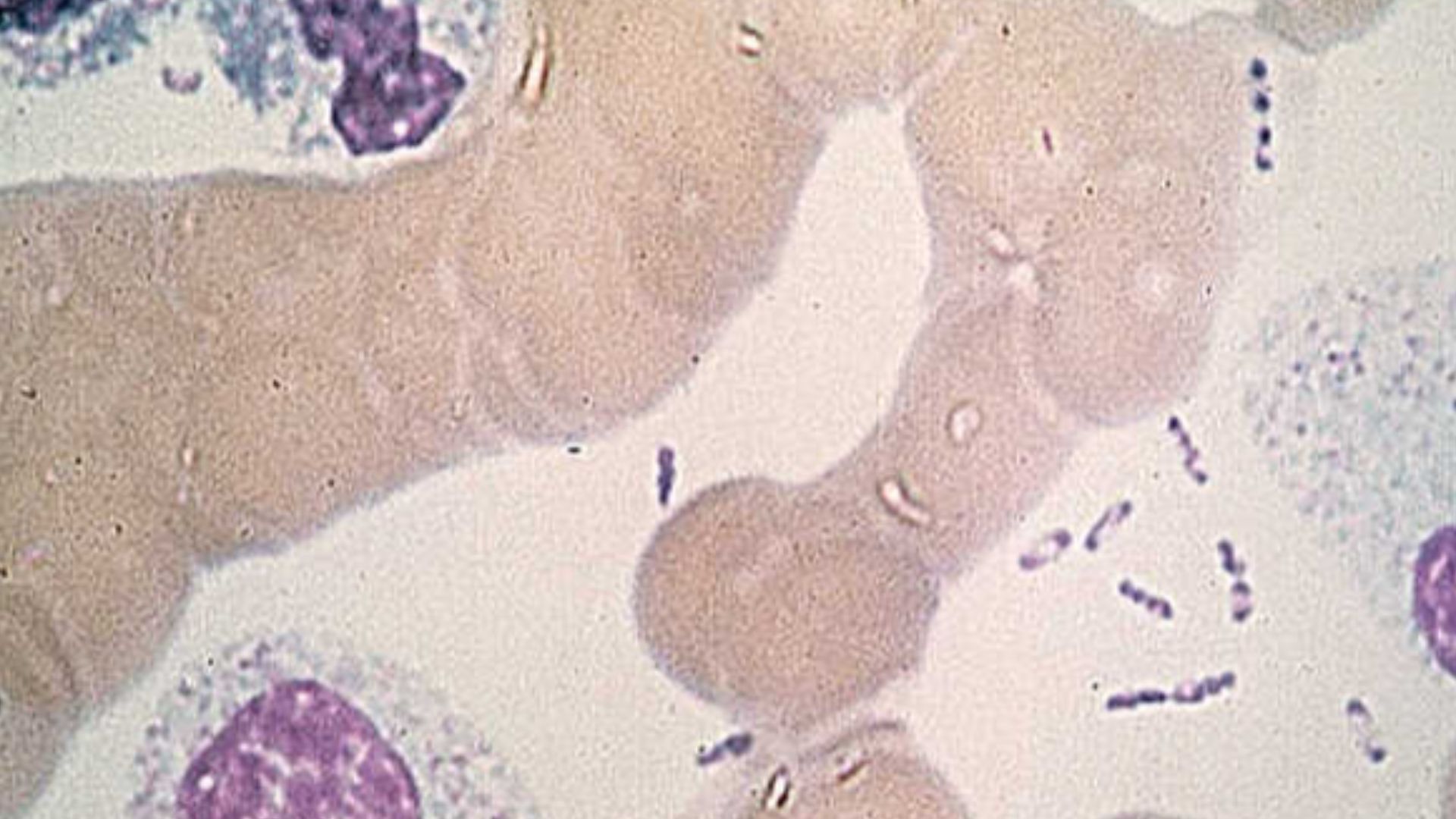

National Library of Medicine - History of Medicine, Wikimedia Commons

National Library of Medicine - History of Medicine, Wikimedia Commons

What The DNA Patterns Say About Speed

Another detail that matters: the bacterial strains found were extremely similar to each other. That kind of genetic similarity often hints at rapid spread, because there’s less time for the pathogen to diversify. In plain terms, it supports the idea that this outbreak moved like a freight train. Once it arrived, it didn’t politely take its time.

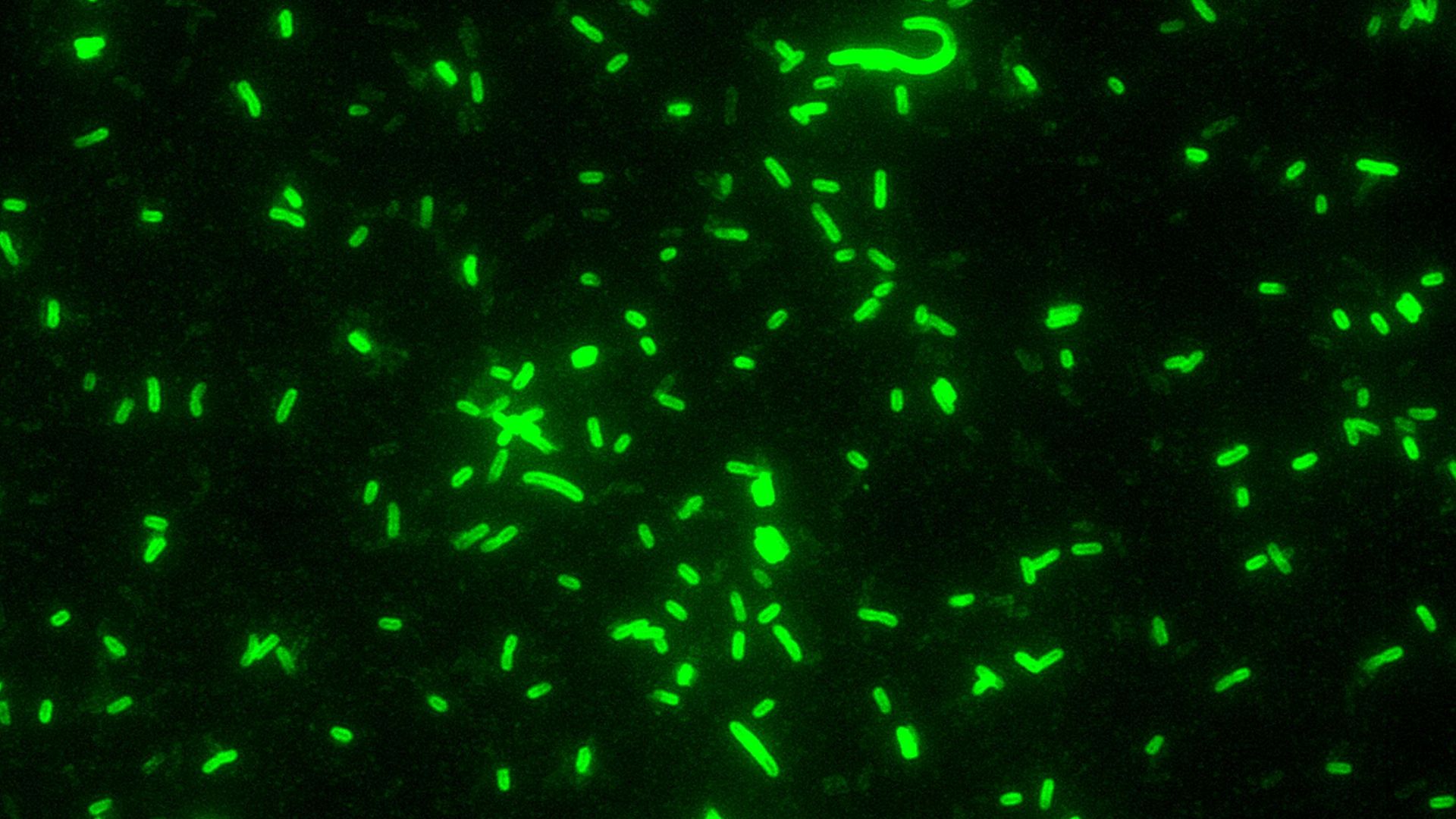

Jonasz Patkowski, Wikimedia Commons

Jonasz Patkowski, Wikimedia Commons

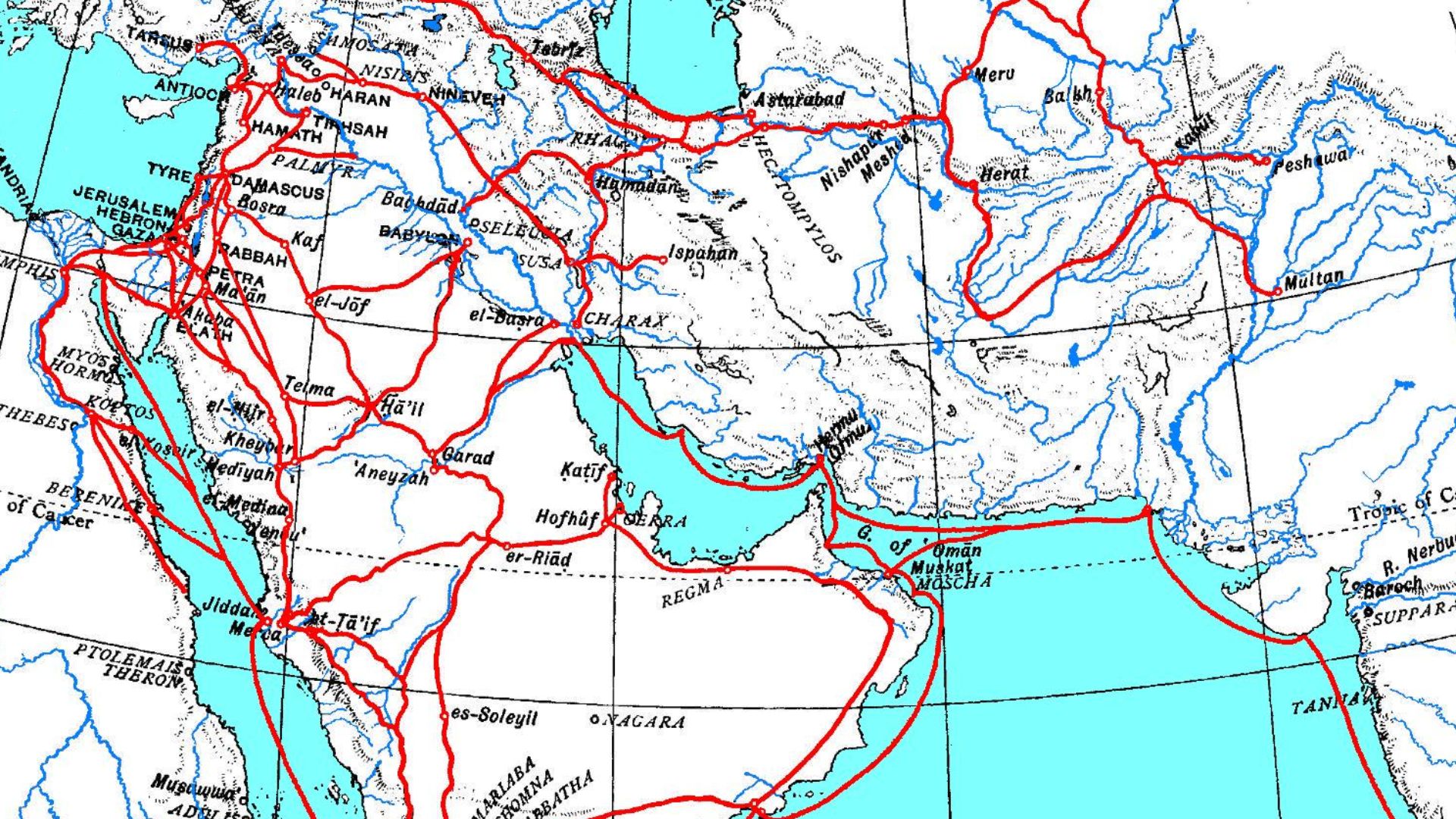

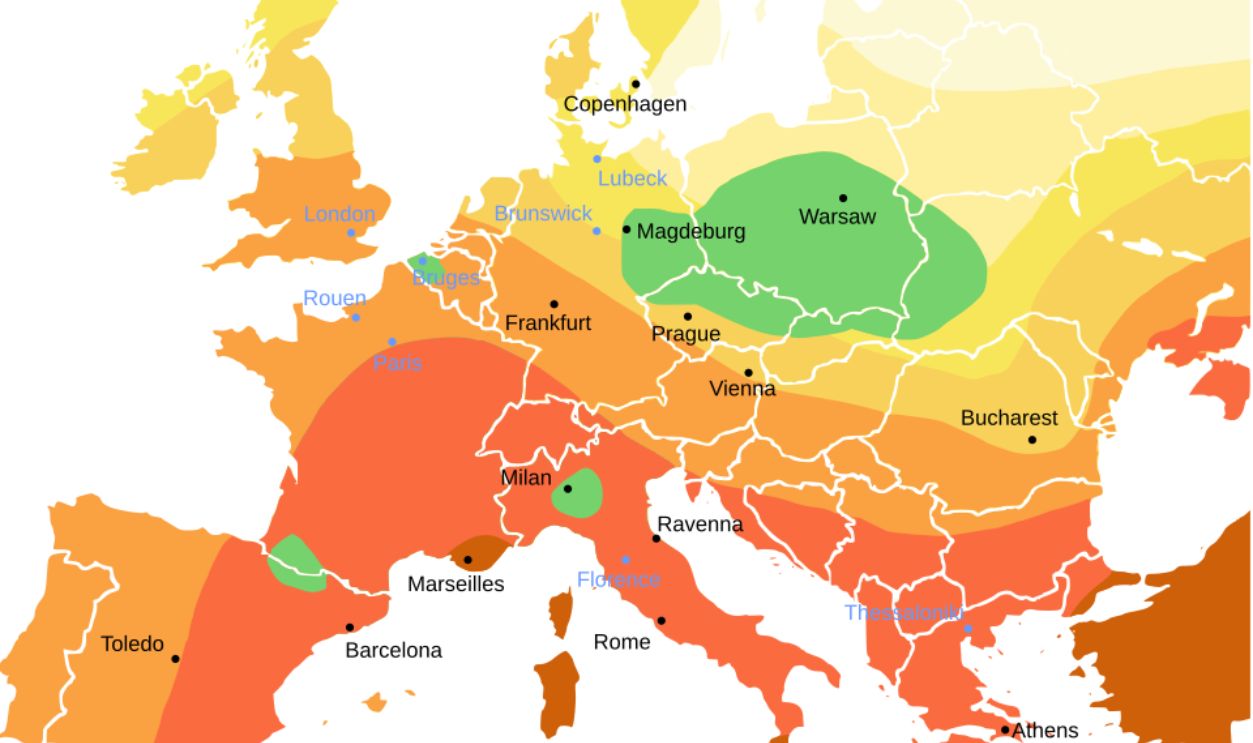

How Movement And Trade Make Everything Worse

We like to talk about the ancient world as if everyone stayed put, but that’s not really how it worked. People traveled for business, politics, religion, family, and survival. Goods moved, and people moved with them, which means pathogens got free rides. Trade networks were basically the ancient version of “sharing germs at the airport,” just with more donkeys.

no idea - see source, Wikimedia Commons

no idea - see source, Wikimedia Commons

The Satisfying Moment When Text Meets Biology

Old historical accounts have always been treated with a little caution, because sometimes writers exaggerate or misunderstand what they’re seeing. But when DNA evidence lines up with the general picture described in those texts, it gives them a lot more weight. Suddenly, those reports don’t sound like dramatic storytelling. They sound like someone watching a catastrophe unfold and trying to make sense of it.

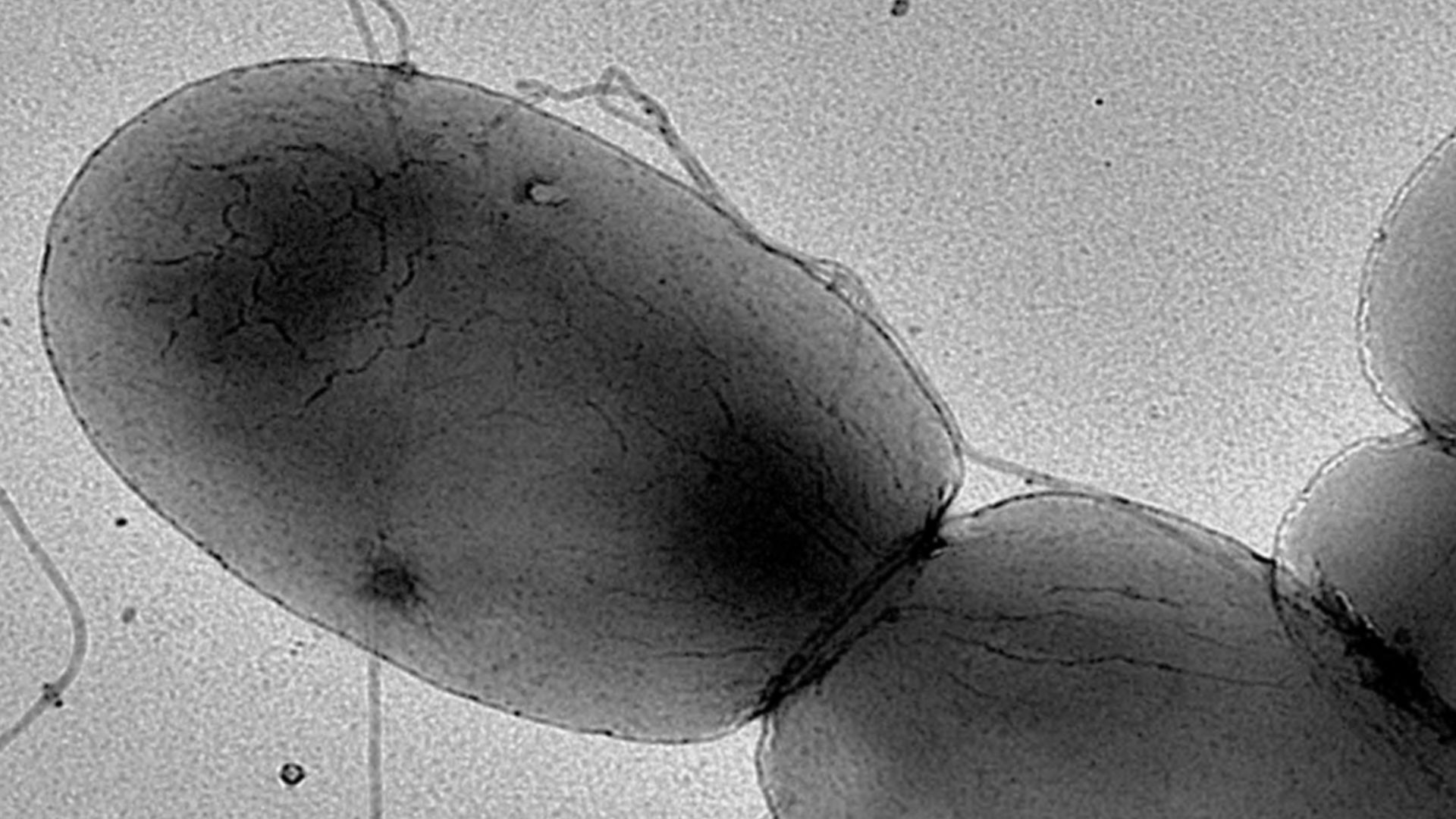

Svante Paabo, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Wikimedia Commons

Svante Paabo, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Wikimedia Commons

The Uncomfortable Truth: Plague Didn’t Just Show Up Once

One of the reasons this matters is that plague isn’t a single historical event. It’s more like a recurring villain that keeps popping back into the story at the worst possible times. Later outbreaks have their own histories, and they reshaped societies too. This research helps connect those dots without flattening everything into one simple narrative.

Andy85719, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Andy85719, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Not One Straight Line, But Multiple Comebacks

A really interesting takeaway is the idea that later plague pandemics weren’t necessarily just one continuous chain from the very first outbreak. Instead, plague likely persisted in animal reservoirs and re-emerged when conditions were right. That means the bacterium can hang around, out of sight, until it gets an opening. If that sounds like something you’d prefer not to imagine, you’re not alone.

Why Cities Were So Vulnerable

Ancient cities were impressive, but they were also fragile in ways modern people don’t always picture. Crowded housing, limited sanitation, and constant contact created the perfect environment for disease. Add supply routes bringing in people and goods every day, and containment becomes almost impossible. It’s a reminder that connection is powerful, but it always comes with a price.

Jim Greenhill, U.S. Army, Wikimedia Commons

Jim Greenhill, U.S. Army, Wikimedia Commons

What This Changes For The Bigger Timeline

Pinning the first recorded pandemic to a specific bacterium helps researchers map how plague has evolved and spread across time. It gives a clear anchor point, like finally marking the start of a long, messy thread. And once you have that anchor, you can ask better questions about what changed between outbreaks and what stayed the same. That’s how you go from a historical mystery to a usable scientific story.

Friedrich Hottenroth, Wikimedia Commons

Friedrich Hottenroth, Wikimedia Commons

Why This Is Still Not Just Ancient History

Plague is rare today compared to what it once was, but it hasn’t vanished. Cases can still appear in some regions, and certain forms can be extremely severe. Knowing its long-term patterns helps scientists understand how it persists and how it can re-emerge. In other words, this isn’t just a history lesson—it’s part of the broader toolkit for understanding disease.

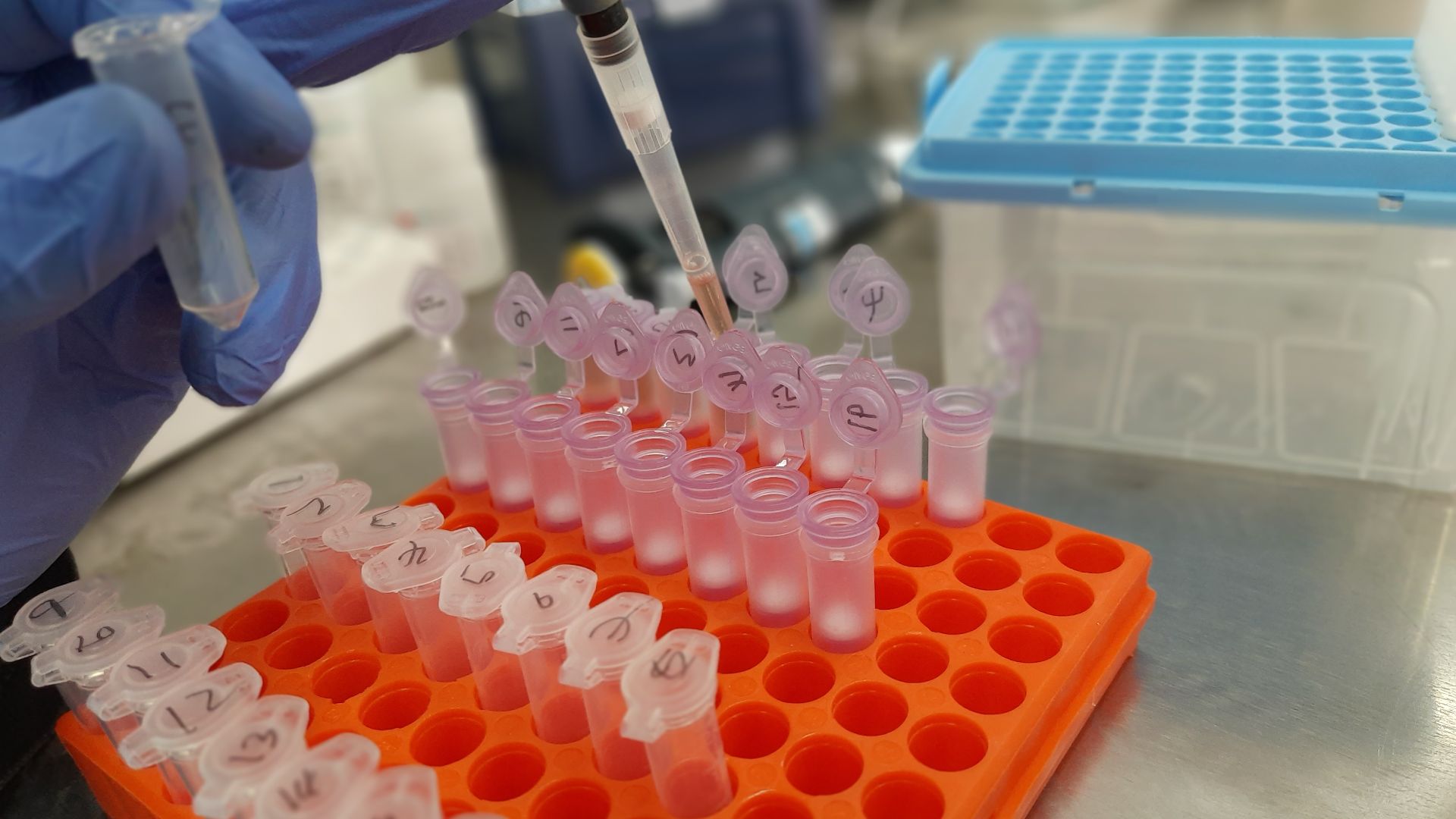

The Tech That Made This Possible

This kind of work relies on modern sequencing tools that can handle tiny, degraded fragments of DNA. Even a few decades ago, a lot of this would have been impossible. Now, researchers can pull meaningful data from remains that have been in the ground for centuries. It’s a reminder that science doesn’t just discover new things—it also revisits old questions and finally answers them properly.

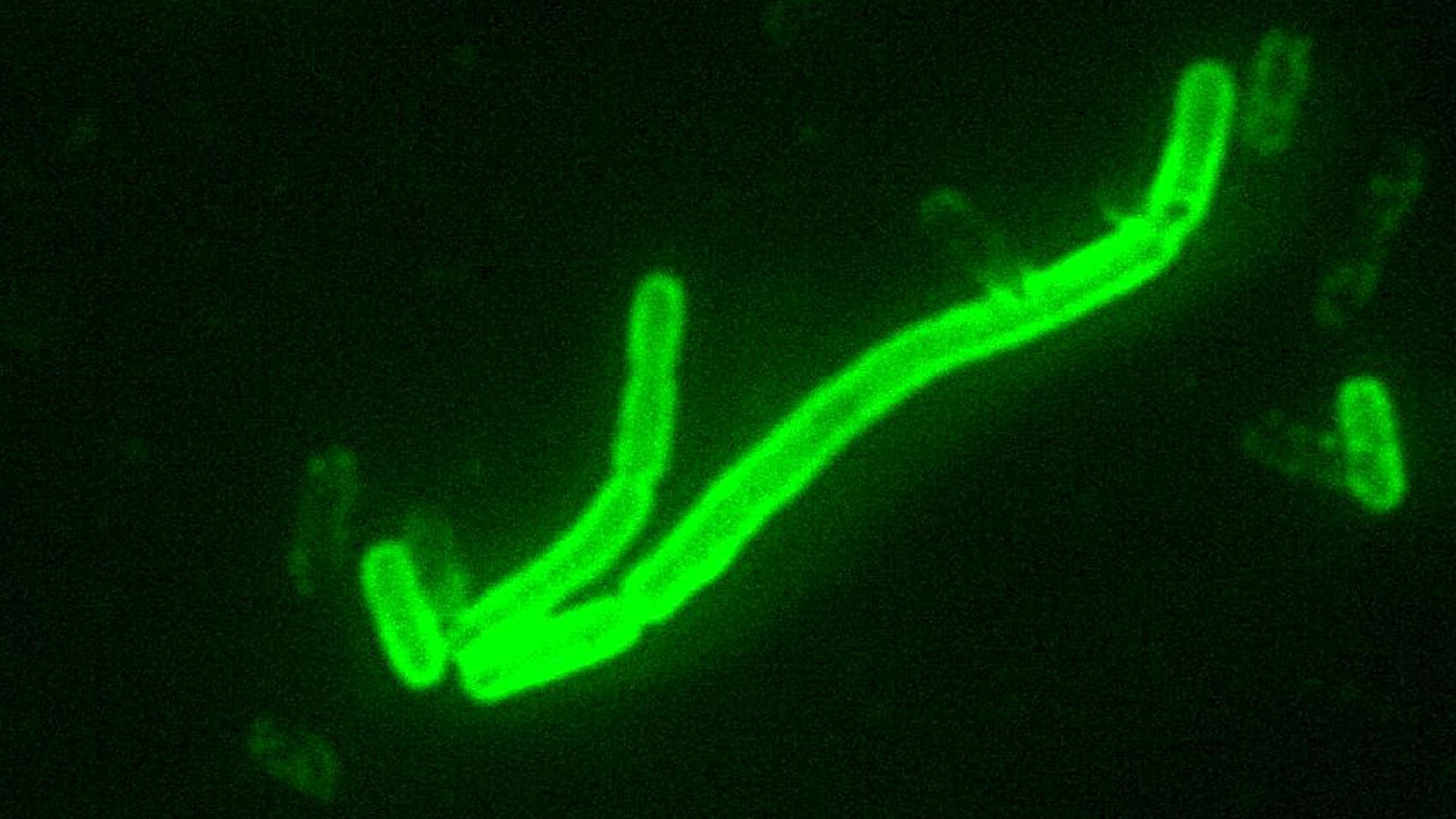

National Institutes of Health (NIH), Wikimedia Commons

National Institutes of Health (NIH), Wikimedia Commons

A Mystery Closed, And A New Chapter Opened

At its core, this is a story about finally naming the thing that haunted an era. A 1,500-year-old pandemic is no longer just a tale told by historians—it’s a documented biological event with a confirmed cause. That doesn’t erase the tragedy, but it does bring clarity. And clarity, especially in the history of disease, is how we stop guessing and start understanding.

Jennifer Oosthuizen, Wikimedia Commons

Jennifer Oosthuizen, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

Archaeologists Find Ancient God In A Sewer

The Twisted Secret We Know About The Hindenburg Disaster

Source: 1