The Aka People

Despite the rapid advances in technology of the last century, there are still places on the planet that function in a way we might think of as much less modern. All around the world, there are isolated tribes whose way of life hasn’t changed much for hundreds of years. There are others, like the Aka, who delicately balance tradition and progress.

African Pygmy Groups

The Aka, also known as the Biaka, are an African pygmy group. They are part of the Mbenga people, nomadic people who live in south-western Africa. Their traditional lands encompass the Central African Republic and the Republic of the Congo.

Max Chiswick, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Max Chiswick, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

What is a Pygmy?

The term pygmy often refers to a specific group of indigenous peoples whose heights tend to be below the global average. A general measure is that the average height for a male is 4 ft 11 in or lower. The term is considered derogatory by many of the people to whom it is applied.

Keystone View Company, Wikimedia Commons

Keystone View Company, Wikimedia Commons

What Causes Pygmyism?

There are numerous theories about why a particular group of people evolve to have a shorter stature than average. In rainforest or jungle environments, the lack of ultraviolet light or vitamin D is proposed as a cause. Some studies show that African pygmies have lower expressions of the genes that encode human growth hormone.

Georges MERILLON, Getty Images

Georges MERILLON, Getty Images

What is a Nomad?

Nomadic cultures are groups of people who do not establish permanent settlements. Nomads can be hunter-gatherers, traders and tinkers, pastoral nomads, or some combination. During the 20th century, nomadic cultures started to decline as industrial, agricultural, and urban cultures increased.

Why Not Settle?

Nomadic cultures are often seen as being much more in tune with natural rhythms. They will follow game animals as they migrate through the year. Rather than settling in one place using up resources, they move on and allow their territories time to replenish and flourish before returning again the next year.

Veronique DURRUTY, Getty Images

Veronique DURRUTY, Getty Images

Origins of African Pygmies

African pygmies, including the Aka, are assumed to be direct descendants of some of the original human populations in Africa. Hunter-gatherer populations migrated from the central African rainforest area millennia ago. African pygmy populations are thought to have diverged from other African populations more than 100,000 years ago.

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Population Numbers

The Aka are a relatively small group. Estimates put the total population of the Aka at roughly 30,000 individuals.

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Mbenga Territories

The Aka are one of a number of pygmy groups broadly categorized under the Mbenga heading. The Mbenga people are found in south-western Africa, across the countries of Cameroon, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, and the Central African Republic.

Veronique DURRUTY, Getty Images

Veronique DURRUTY, Getty Images

Aka or Baaka?

The Aka refer to themselves as the Baaka, which roughly translates to “Aka people.” They refer to the specific language they speak as “Aka.” In other dialects, the Aka people are known as the Biaka, the Babenjelé, or the Bambenga.

Veronique DURRUTY, Getty Images

Veronique DURRUTY, Getty Images

The Aka Way of Life

The Aka are a hunter-gatherer culture. They get virtually all of their resources and food by foraging or hunting in the forests they inhabit. Hunter-gatherers follow animal migrations and seasonal crops, hence the nomadic nature of the culture.

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

The Aka and their Neighbors

Although the Aka obtain most of their resources by foraging, they also have good trade relationships with nearby villages. Common agricultural produce is often traded for items to which the Aka have access. Bushmeat and honey are traded for things like cucumber, mango, or rice.

The Aka and Ebola

One negative result of the Aka’s lifestyle is extremely high rates of seropositivity for the Ebola virus. This means the virus is found very commonly in their blood, a result of much higher interaction with jungle animals than urban or agricultural peoples might have.

VALENTIN NVJ, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

VALENTIN NVJ, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Language of the Aka

While the Aka use some common parts of the Bantu and Ubangian language groups, about 30% of their language is unique to their small group. Much of the unique language has to do with their relationship with the forests they inhabit, including specific botanical and honey-harvesting ideas.

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

UNESCO Recognition

Due to the unique nature of much of the Aka culture, the oral traditions of the tribe were given the status of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2003 by UNESCO.

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Gender Roles in Aka Society

Unlike many agricultural and urban societies, gender plays little role in who does what in Aka society. Men are just as likely to perform traditionally feminine tasks, such as caregiving, while women often become remarkably proficient hunters.

Max Chiswick, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Max Chiswick, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Aka Parenting

The Aka put a great deal of importance on being physically close to their children as soon as they are born. There is a distinct lack of cots in Aka camps as being away from a child for so long a time is unheard of. Parents are always very close to their children.

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Aka Fathers

Fathers in Aka camps are in contact with their children an astounding five times more frequently than any other society on the planet! Fathers bring their children to social events, and even offer nursing children a nipple to nurse on for comfort.

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Aka Mothers

The strong bond between married partners in Aka society means that Aka mothers have the opportunity to pursue things like hunting and leisure activities while the baby’s fathers take care of feeling and caregiving. This division of labor allows both parents the time to be both caregiver and provider for the tribe.

L. Petheram, Wikimedia Commons

L. Petheram, Wikimedia Commons

The Effect of the Slave Trade

Colonialism and the slave trade of the 18th century affected the Aka like it did many people on the African continent. Those trying to escape the slave trade often migrated into Aka territories, and some tribes were absorbed into the Aka society and way of life.

Unknown Author, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

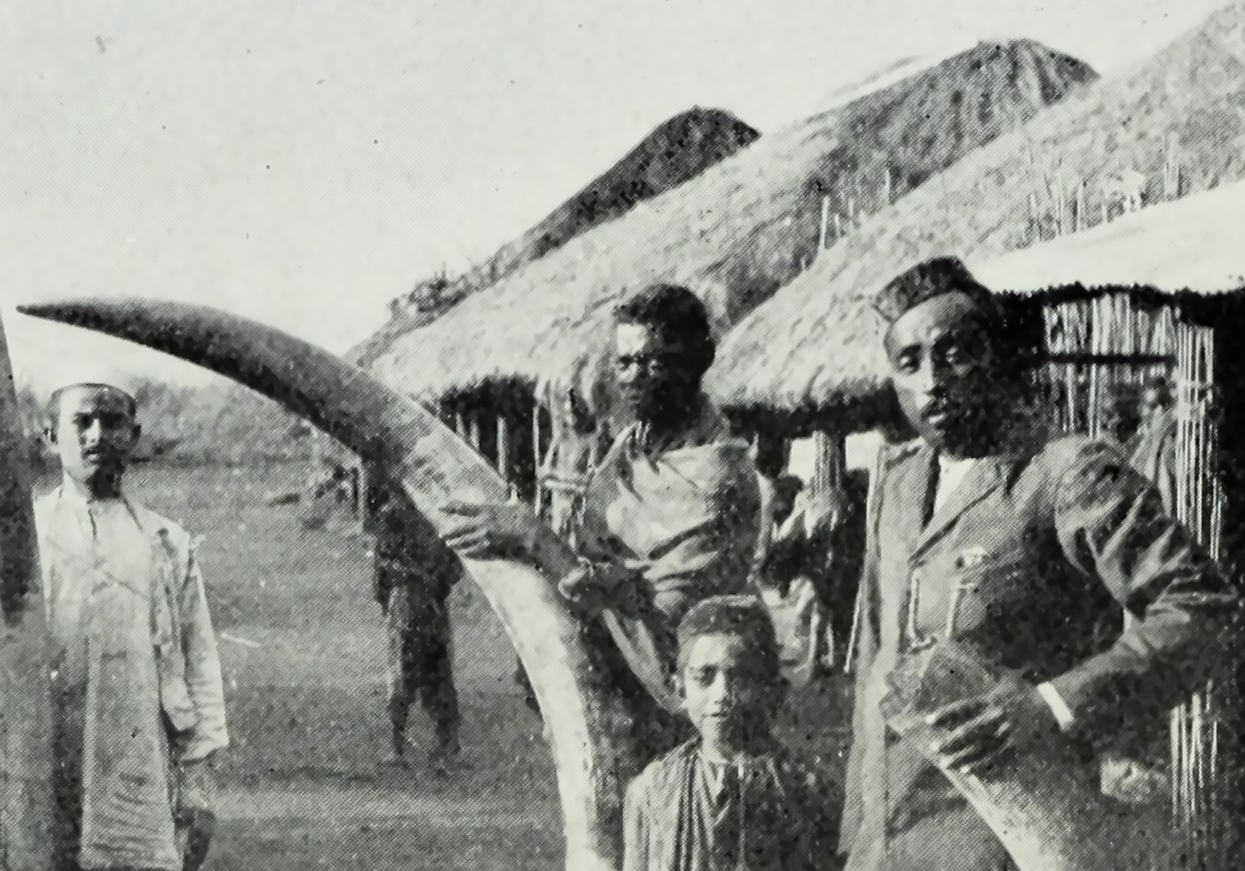

Elephant Hunters

Due to their long history of hunting bushmeat, the Aka became highly-regarded as elephant hunters in the 19th century. The Aka would hunt the animal and harvest its ivory. Tribes they traded with would then pass the ivory on to Europeans eager for the valued material.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

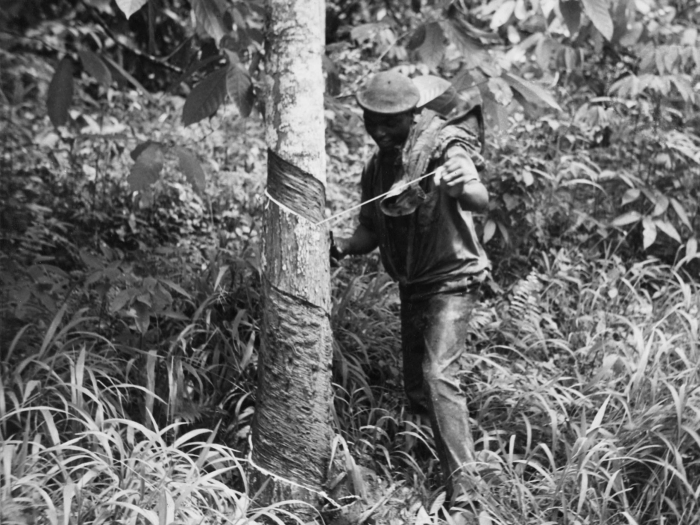

The Effect of the Rubber Trade

Another colonial expansion in French Equatorial Africa had to do with increased need in European countries for rubber. Slaves from rubber plantations would sometimes escape into the jungles, which placed undue stress on the resources of the Aka who lived in these territories.

National Museum of World Cultures, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

National Museum of World Cultures, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Rubber Trade and Hunting

The increased demand for bushmeat from slaves escaping the rubber trade forced the Aka to innovate new ways of hunting. Alongside the traditional spear hunting that they had used for centuries, net hunting was introduced, and became associated with the female hunters of the tribes.

Defying French Rule

As late as the 1930s, the French still held sway in many areas that encompassed traditional Aka lands. The colonial governments tried to force the Aka to give up their nomadic lifestyle and move into villages, but most instead fled to the jungles where they knew they would be safe.

Modern Economic Pressure

Increased need for resources and increased expansion of urban and agricultural populations has changed the ways in which the Aka support themselves. The coffee industry, lumber industry, and ivory trade have become significant ways in which the Aka support themselves and trade with neighboring tribes.

Georges MERILLON, Getty Images

Georges MERILLON, Getty Images

The Aka and Enslavement

Sadly, many contemporary Aka are enslaved by the majority Bantu populations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). From birth to death, many Aka are used to provide food and manual labor in Bantu jungle villages.

Andrew Aitchison, Getty Images

Andrew Aitchison, Getty Images

Difficulties with Discrimination

African pygmies make up less than 10% of the population in their traditional areas, and are subject to discrimination as a result. In 2022, a group of indigenous organizations finally had the Promotion and Protection Rights of the Indigenous Pygmy Peoples signed into law in the DRC.

JMGRACIA100, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

JMGRACIA100, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Problem of Deforestation

As with indigenous groups in many parts of the world, the Aka are threatened by deforestation from the lumber and agricultural industries. As the need for wood and grazing land increases, nomadic jungle tribes are forced to exist in smaller and smaller territories every year.

Georges MERILLON, Getty Images

Georges MERILLON, Getty Images

Conservation Work

As a result of many of these difficulties, the Aka works closely with conservation organizations to combat the problems of industry. This work includes protecting gorilla habitats and forests, and working to ensure the rights of indigenous peoples throughout the continent.

Music of the Aka

Aka music is of great interest to ethnomusicologists. Experts note that the level of complexity in Aka music took until the 14th century to be achieved by more advanced European society. Along with their language, their music is recognized as significant by UNESCO.

MONUSCO Photos, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

MONUSCO Photos, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Polyphonic Music

The Aka’s polyphonic music is based on vocal repetition, something like a round in European music. The interaction of each singer and their individual knowledge of a song can produce almost endless variations of a song. Much of their music is created through improvisation.

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Liquindi

Another unique kind of music, Liquindi is usually only practiced by women in Aka culture. It is music using water as a percussion instrument, and involves repeated splashes mixed with beats from cupped hands on the water’s surface.

Max Chiswick, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Max Chiswick, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Hindewhu

Hindewhu utilizes both vocal singing and a papaya-stem whistle. The name of this style of music is an onomatopoeia for how the combination of singing and whistling sounds while performed. It is most often used to announce the return of a hunting party.

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Wikimedia Commons

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Wikimedia Commons

The Aka’s Greatest Hits

The uniqueness of Aka music has drawn much interest from researchers and musicians alike. Aka musicians appear on a number of collections, including BOYOBI: Ritual Music of the Rainforest Pygmies and Bayaka: The Extraordinary Music of the BaBenzele Pygmies, compiled by Louis Sarno.

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

The Aka in Popular Music

Aka music has also found its way into some popular music since first introduced in the 1960s. Electronic group Deep Forest included Hindewhu in their track “Hunting.” Herbie Hancock includes some in his song “Watermelon Man”, which was later sampled by Madonna in her song “Sanctuary.”

Dmitry Rozhkov, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dmitry Rozhkov, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Song from the Forest

The 2013 film Song from the Forest tells the tale of American Louis Sarno who lived with the Aka for 25 years. Sarno traveled with them, recording their music, and learning their unique way of life.

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Writings about the Aka

Sarno also published a book of the same name about his time with the Aka that was the basis for the 2013 film. There is also an academic study of the unique Aka music from Oxford University Press called Seize the Dance!

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)

Tondowski Films & Friends, Song from the Forest (2013)