Mining The Depths

Kargaly’s giant copper mine spanned the end of the Copper Age in the fourth millennium ВСЕ to the dramatic end of the Bronze Age in the second millennium. Situated in the Ural Mountains, Kargaly straddled Europe and Asia, producing a vital component of the bronze that would advance whole civilizations. This is its fascinating tale.

Two Worlds Collide

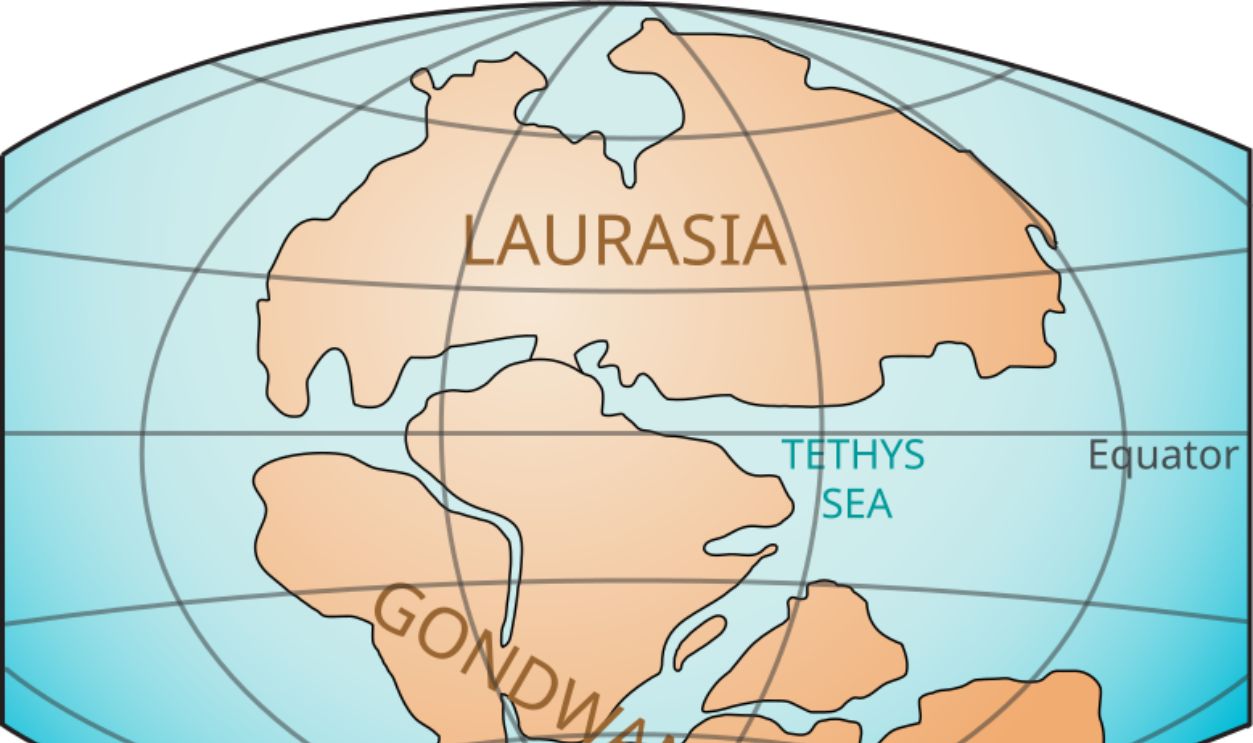

The story begins with a continental collision that made copper mining possible at Kargaly. In a giant geological confrontation 250 million years ago, a supercontinent called Laurasia, now making up most of Europe, slowly bulldozed over island chains and rammed into Kazakhstania.

Lennart Kudling, Wikimedia Commons

Lennart Kudling, Wikimedia Commons

From Sea To Sky

The conjoining of this supercontinent and its smaller sparring partner thrust former coastlines upwards to form the Urals. The force of continental drift inserted massive segments of copper-rich ocean floor into giant mountains. Million of years later, the Copper Age would take notice.

ugraland , CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

ugraland , CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Tools For The Job

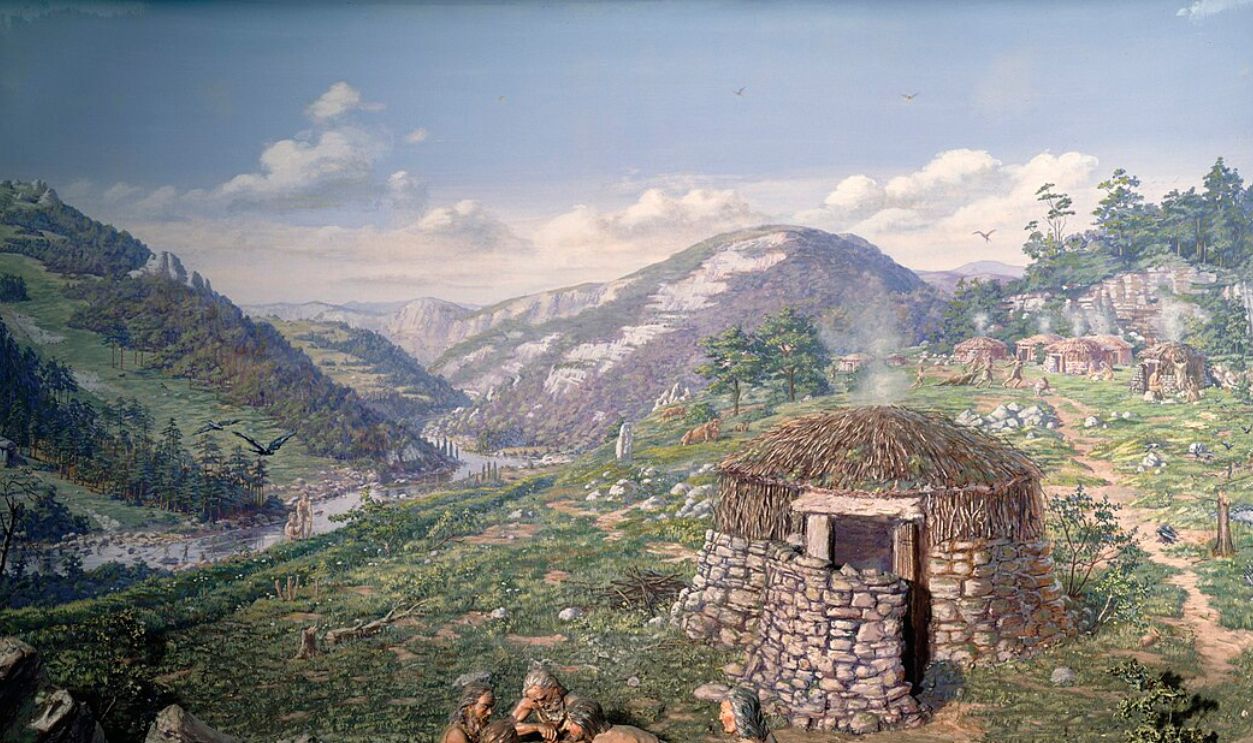

Prehistoric humans developed increasingly sophisticated stone tools, culminating in the Late Stone Age known as the Neolithic. Around the fifth or fourth millennium BCE, humans started to shape copper deposits into tools and ornaments. Then they figured out how to smelt the metal.

Unknown Author, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Copper Innovation

Molten copper could be poured into molds to create tools and weapons. It was near the end of the Copper Age, around the fourth millennium BCE, that the nomadic tribes of what’s now southern Russia decided to excavate copper from the Urals with great determination.

Sergei Ivanovich Borisov, Wikimedia Commons

Sergei Ivanovich Borisov, Wikimedia Commons

Premium Sandwich

The Urals contained sandwiched layers of sedimentary and volcanic rock, with the sedimentary layers containing the valuable copper. Initially, the nomads dug at the copper on or near the surface. It was tough work, and the landscape was brutal. But they turned to the gods for help.

ugraland [1], Wikimedia Commons

ugraland [1], Wikimedia Commons

Prized Bronze

Copper was useful, but had a big flaw: it was soft. But prehistoric metallurgists discovered a trick. They could combine copper with tin to make bronze. The discovery of this strong alloy accelerated the development of multiple civilizations in the Bronze Age, and Kargaly was key.

The Bronze Age Collapse - Mediterranean Apocalypse, Fall of Civilizations

The Bronze Age Collapse - Mediterranean Apocalypse, Fall of Civilizations

No Garden Plots

But the steppes were an unforgiving environment. The invention of farming that had swept through much of the world bypassed the southern Urals. Neither the land nor the climate made agriculture a promising venture. And the same factors made for brutal mining conditions.

Charcoal On Demand

Miners had to deal with bitter cold, and smelting requires heat, such as by burning wood. But charcoal was also crucial. By covering a wood pile with earth, perhaps also with branches and straw, these prehistoric experts could prevent burning wood from turning directly into ash.

Raising The Temperature

This was a critical component of Kargaly’s operations because normally wood does not burn hot enough to smelt copper. Charcoal, however, burns at a higher temperature. But trees were a rare commodity on the wide-open plains of the steppes. And finding water also loomed large.

Vital Imports

Fortunately, being nomadic, the Kargaly clans were well versed in moving goods around. They likely transported water on their own, and perhaps traded their copper for the wood they needed to smelt more. They also likely took animals as payment for copper, serving various purposes.

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Wikimedia Commons

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Wikimedia Commons

Animal Products

Without local agriculture, the animals they imported were vital to make sure miners and other workers were fed. Furthermore, animal skin provided clothing, and the mine’s tunnels could be lit by burning animal fat. But in these dangerous times, gods would have to be placated too.

Sergei Ivanovich Borisov, Wikimedia Commons

Sergei Ivanovich Borisov, Wikimedia Commons

The Power Of Sacrifice

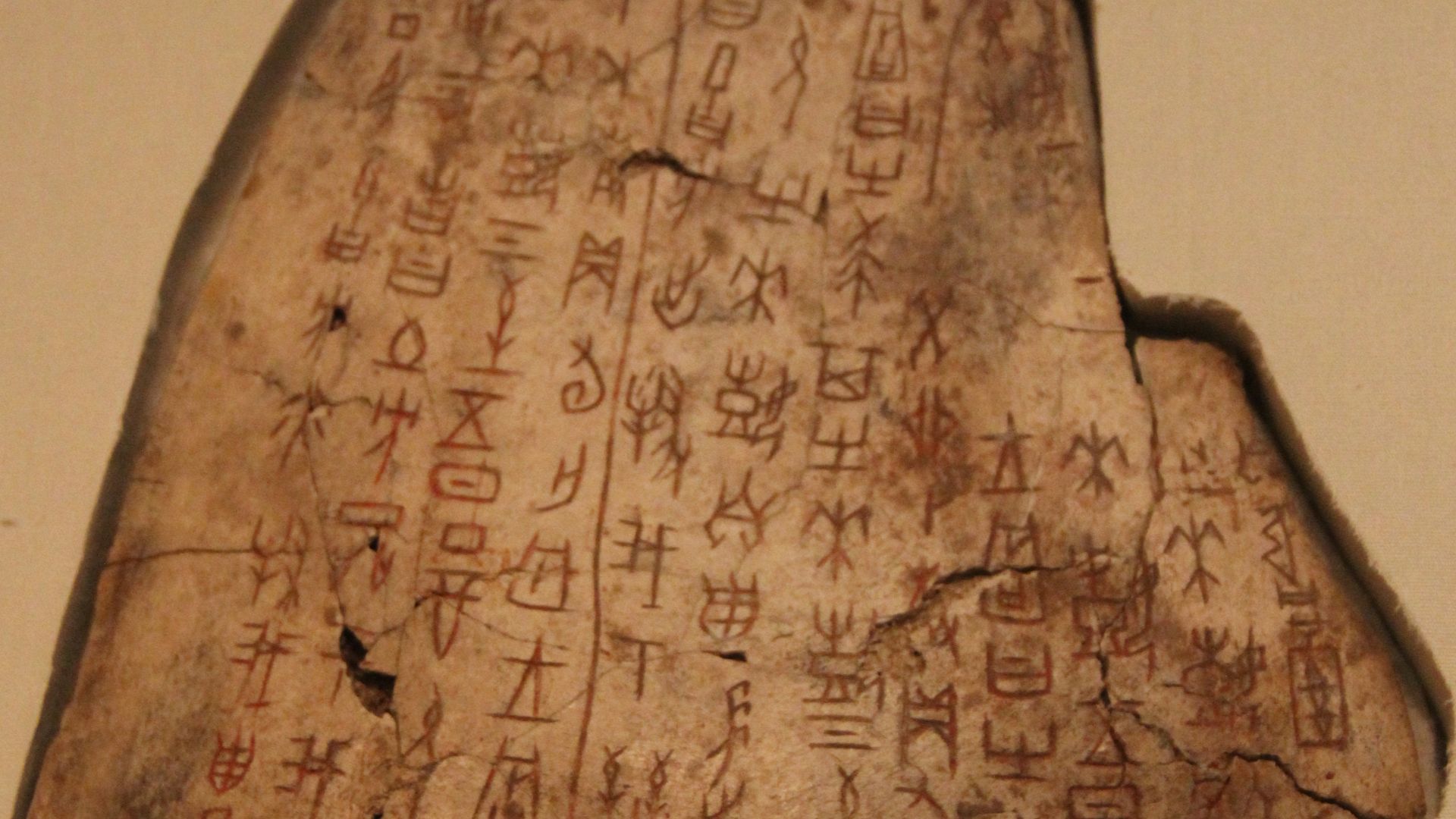

Animals were also used as sacrifices to please heavenly and earthly powers, and artifacts reflected their importance. Oracle bones helped the divinatory experts predict conditions and recommend actions. And, whether made of bone, stone, or metal, artifacts played another role.

A Symbolic Birth

Common through the Eurasia of the Bronze Age were items representing masculine and feminine beings and objects. To remove metals from Mother Earth was like the act of giving birth, with frequent and elaborate rituals helping to ensure success in this serious business.

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Grave Concerns

And this serious business involved experts who were clearly valued. The graves of the Kargaly inhabitants reflect the status of different classes of people. The metalworkers were the elite experts in their craft, and so were often buried with the most valuable of the artifacts found.

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Following The Steps

And these experts had to guide workers through a series of complicated stages to extract the ore and turn it into refined copper. The first step was producing the charcoal that was so important for smelting copper. It could boost temperatures to 1,800°F (1,000°C) or even higher.

Jonathan Zander, Wikimedia Commons

Jonathan Zander, Wikimedia Commons

Retrieving The Ore

Next up: processing the copper ores. The ores were mostly malachite and azurite, mined from the sedimentary rocks of the mountain range. Miners used stone and bronze tools to get at the ore. Then it would be broken into smaller pieces, and perhaps refined with some initial roasting.

Smelting Time

Now was the time for the actual smelting, which could take place in a pit furnace, or a clay furnace situated in a shaft or on the ground. Workers would prepare layers of ore separated by layers of charcoal. The charcoal would be lit, and bellows or blowpipes would feed the fire.

Brian Masney, Wikimedia Commons

Brian Masney, Wikimedia Commons

Separation And Purification

At a high enough temperature, the minerals in the ore would break into their constituent parts. Heating would separate the copper from impurities in the oxide ore, as well as the flux added to help the process along. Sulfide ores first had to be converted to oxide ore through roasting.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

A Heap Of Waste

Impurities in the original ore along with fluxes like silica combined to form slag as they cooled. This produced a glasslike waste product that would accumulate at the site. Meanwhile, the copper-rich ore could be smelted again and again until the copper reached the desired purity.

S. Rae from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

S. Rae from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

Product Line

Once the metalworkers had something close to pure copper, they could pour the molten copper into clay molds to produce ingots, tools, or artistic creations. It’s believed that rituals and symbolism would accompany every stage of smelting, as spirituality infused the process.

Chris 73 / Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons

Chris 73 / Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons

Spread Wide And Far

The Kargaly operation was so important that its copper spread through a vast area, mostly west of the region. A so-called Copper Way formed a commercial network covering 400,000 square miles (1 million square kilometers) of trading routes, with eager customers all along the way.

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

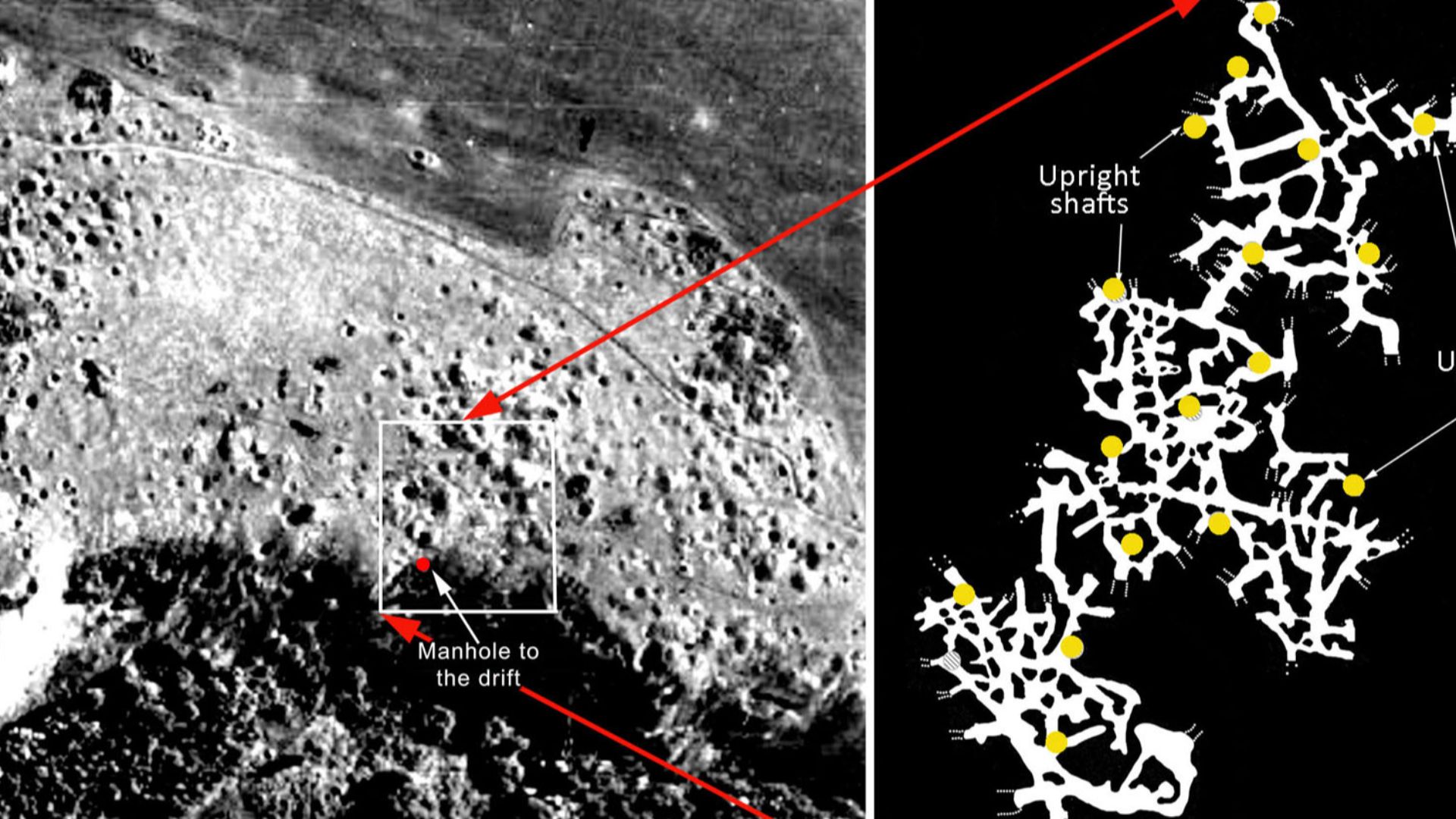

Digging Deep

And the scale of the mining operations at Kargaly, the largest of its kind during the Bronze Age, is apparent. Archaeologists have counted over 35,000 mining shafts, pits, and tunnels. After exhausting the deposits on the surface, miners dug shafts up to 130 feet (40 meters) deep.

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Following The Ore

Great ingenuity can be seen at all stages of the mining and refining process. Elaborate tunnels and chambers followed the ore wherever it could be found. Test pits and shafts probed possible locations of ore, which required perseverance due to the unpredictable location of the copper.

S. Rae from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

S. Rae from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

Prehistoric Tool Time

A wide range of stone tools point to a sophisticated understanding of the mining process and how best to crush ore and cast molds, with impressive forging hammers and anvils at the center of the process. And all these tools were used in harsh conditions not for the faint of heart.

Limelightangel, Wikimedia Commons

Limelightangel, Wikimedia Commons

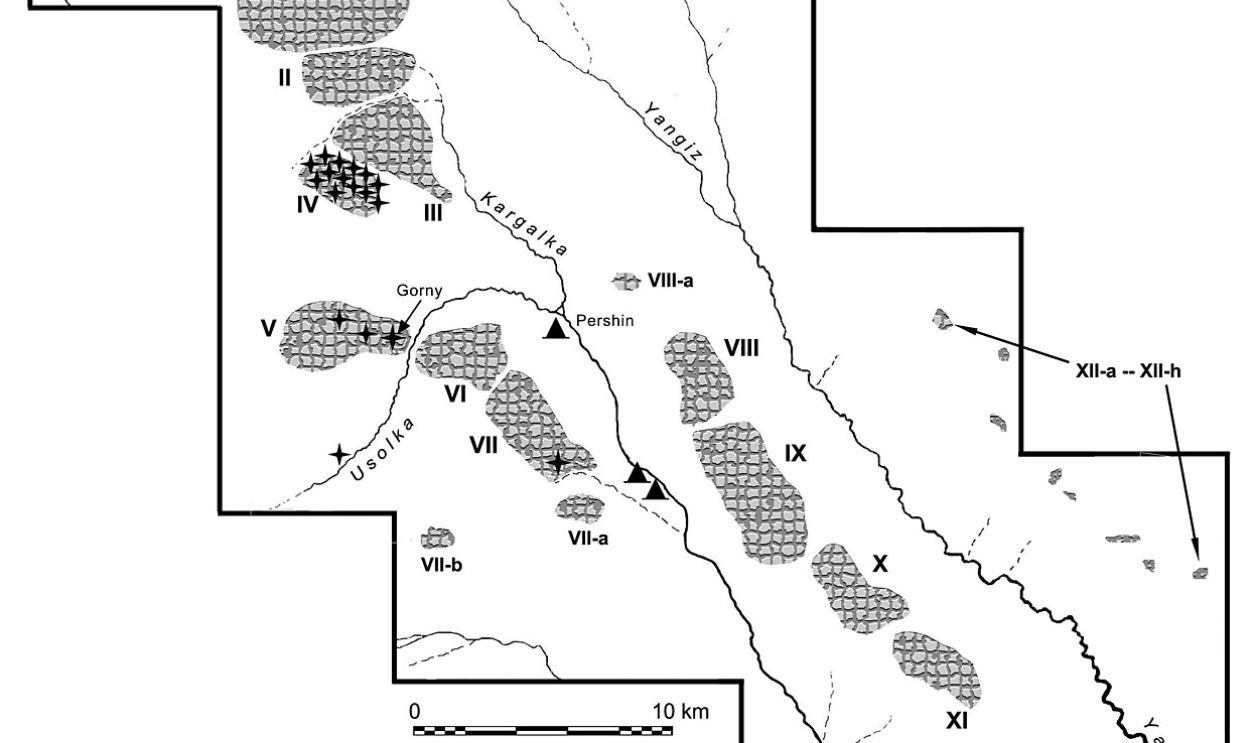

Vital Work

Archaeologists have found remnants of 20 settlements in the Kargaly area, as well as burial mounds (called kurgans). The communities were all situated in the ore field, near where mining or smelting was taking place, an indication of how vital the mining of copper was to this society.

Low-Water Mark

The Kargalka River and tributaries were nearby, providing much-needed water, but not enough for the full scale of Kargaly’s mining operations. Gorny, which is the most thoroughly examined community on the ore field, is near the Usolka River, and was a kind of hub for mining activities.

Сергей Метик, Wikimedia Commons

Сергей Метик, Wikimedia Commons

Never Enough

The ore field is located in the present-day Orenburg region, along the southeastern edge of European Russia. Forests cover less than 2% of the area, and water sources are limited. Even though settlements were close to ore, wood, or water, local supplies were never enough.

Mainly Meat

Kargaly communities were able to trade with other steppe communities, as well as trading further afield. It seems the miners’ diet mainly depended on livestock obtained as trade for copper. The evidence shows no one was farming vegetables in the area during the Bronze Age.

Increasing Flow

The overall picture is one of a major “prehistoric industrial center,” with various stages of the mining process integrated into a sophisticated flow. The Kargaly operation managed to keep growing, peaking a little before the end of the Bronze Age, when Srubnaya culture dominated.

Waste Reduction

All told, around 55,000 to 120,000 tons of copper were mined, and with those results came a lot of waste. Around 250 million tons of rock had to be cast aside to get to the copper, with refining and smelting leaving huge piles of slag. And what trees had been around were soon cut down.

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

End Of An Era

With a huge amount of water and wood required, eventually the mining operations became unsustainable. Around 1400 BCE, the last copper was extracted at Kargaly as the Bronze Age neared its conclusion. It seems environmental depletion and devastation had become too much.

Almatoswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Almatoswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Escape From Mycenae

Though it is possible to construct another theory. The so-called Late Bronze Age collapse was a widespread disaster visited upon ancient civilizations of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East. Residents of Mycenaean, Hittite, Minoan, and Egyptian cities fled to farms and villages.

Andy Hay from UK, Wikimedia Commons

Andy Hay from UK, Wikimedia Commons

Lost Letters

The loss of urban civilization saw a collapse in population levels, trade, and literacy. Greek civilization lost its writing system and many forms of art, for instance. Earthquakes, drought, peasant revolts, and the collapse of trade routes have all been invoked as explanations.

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Chernykh Evgenij, Wikimedia Commons

Buy Local

Palaces were abandoned, cities became ghost towns, and everything seemed to go local for a while. What followed was the so-called Iron Age, which got around the difficulty of finding and trading tin, and offered an even harder metal to boot. But getting to that point was arduous.

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

Out Of Stock

It seems the Bronze Age collapse happened around 1200 BCE, a couple of centuries after Kargaly closed shop. It likely wasn’t widespread catastrophes that shut down Kargaly’s operations. It was instead the local catastrophes of deforestation, waste, and scarce water.

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

Staying Power

Nomadic tribes abandoned mining, but not their lifestyle or their lands. They continued to rule the steppes for millennia, until the Russian Empire took over. The new rulers reactivated the mine in the 18th century, and copper trade took off again, reaching even England and France.

Vasily Sadovnikov, Wikimedia Commons

Vasily Sadovnikov, Wikimedia Commons

Data Mining

But it’s the Bronze Age activities at Kargaly that truly capture the imagination. At around 190 square miles (500 square kilometers), the mining area was enormous. And as an archaeological site, the region provides a vivid look at the harsh lives of people around 3000 to 1400 BCE.

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

Connecting The Dots

Kargaly may also offer a cautionary tale about the consequences of environmental destruction in an age of interconnected economies. Kargaly simply couldn’t sustain itself amidst scarce supplies and poisoned pastures. And with its copper no longer traded, there’d be ripple effects.

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

The End Of The Line

The networks that connected Bronze Age kingdoms were already collapsing, and the loss of Kargaly’s copper would presumably have accelerated the disintegration of trade routes. The ingenuity of Kargaly and the brilliance of the Bronze Age had both come to a crashing halt.

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

Anton Yefimov, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

The Bronze Age Collapse—What It Is And Why It Happened

Unraveling The Mysteries Of Göbekli Tepe, A Pre-Pottery Neolithic Treasure Trove

We Have Proof That Neanderthal Kids Were Picking Up Fossils And Storing Them

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12