TB1's Missing Foot

One skeleton is making medical historians question their entire timeline. The bones belong to someone who survived major surgery before farming, before metal, before civilization as we know it. Their healed leg rewrites human capability.

Agricultural Theory

For decades, scientists believed surgery was born from necessity when humans settled down to farm around 10,000 years ago. The Neolithic Revolution brought crowded communities, new diseases, and agricultural accidents. This theory made sense: permanent settlements meant specialized roles, including healers who could develop complex surgical skills.

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

France's Record

A 7,000-year-old skeleton discovered at Buthiers-Boulancourt, France, held the crown for the earliest known amputation until 2022. This elderly Neolithic farmer had his left forearm surgically removed just above the elbow, and the bone showed clear healing. The procedure required impressive anatomical knowledge.

Sarah Murray from Palo Alto, CA, Wikimedia Commons

Sarah Murray from Palo Alto, CA, Wikimedia Commons

Borneo's Rainforest

Picture Indonesian Borneo's Sangkulirang-Mangkalihat Peninsula: a rugged limestone karst landscape where dense tropical rainforest meets towering cliffs, accessible only by boat during certain seasons. The region experiences extreme heat and humidity, perfect conditions for rapid wound infections that would doom any surgical patient.

Cave Art

Before the surgical discovery, this Borneo region was already famous for harboring humanity's oldest figurative art. Cave walls throughout the area display wild cattle and other animals painted at least 40,000 years ago, along with striking red hand stencils and zigzag patterns.

@ photo Luc-Henri Fage, www.fage.fr., Wikimedia Commons

@ photo Luc-Henri Fage, www.fage.fr., Wikimedia Commons

The Patient

Meet TB1—a young adult whose skeletal remains tell an extraordinary story of survival. Bioarchaeological analysis revealed this individual died between ages 19 and 20, but the stump of their left leg showed they'd lived 6–9 years post-amputation based on bone remodeling patterns.

Childhood Trauma

The reason for TB1's amputation remains medicine's 31,000-year-old mystery. Researchers found no evidence of animal bite marks, crushing of the bone, or accident-related fracturing at the amputation site. The clean, sloping cut ruled out crocodile attacks, tiger maulings, or traumatic injuries common in prehistoric life.

Surgical Decision

Imagine the moment when TB1's community faced an impossible choice: attempt an untested, potentially fatal surgery or watch the child die from spreading infection. Someone, perhaps a respected elder or experienced healer, made the call that removing the limb offered the only survival chance. This decision reveals a profound understanding.

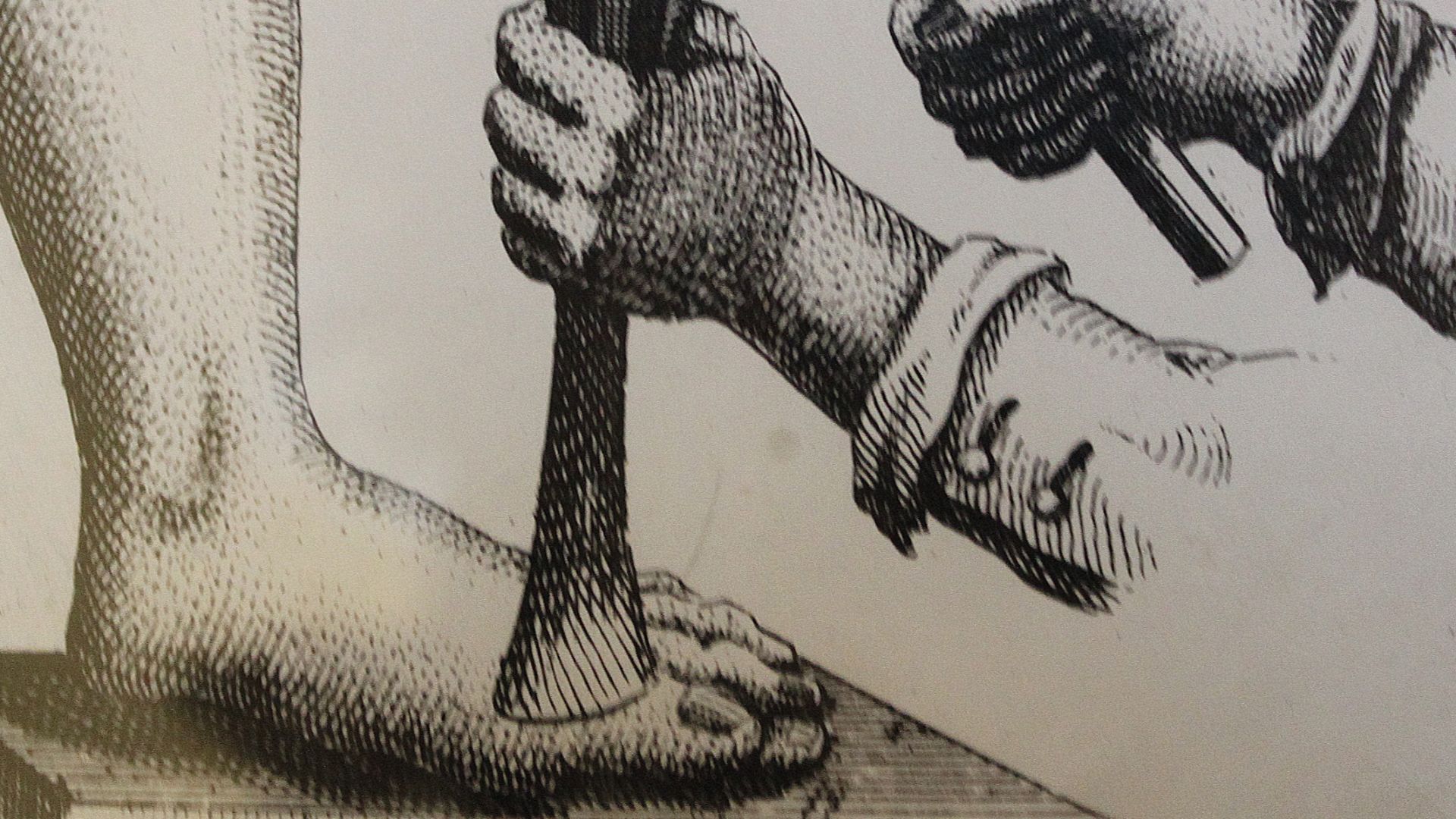

Stone Tools

No metal scalpels or surgical saws existed in 29,000 BCE—only stone, bone, and bamboo implements sharpened to razor edges. The surgical team likely used obsidian or chert blades, materials that can be knapped into edges sharper than modern steel scalpels. Radiographic analysis of TB1's bones revealed clean cutting margins.

Khalid Mahmood, Wikimedia Commons

Khalid Mahmood, Wikimedia Commons

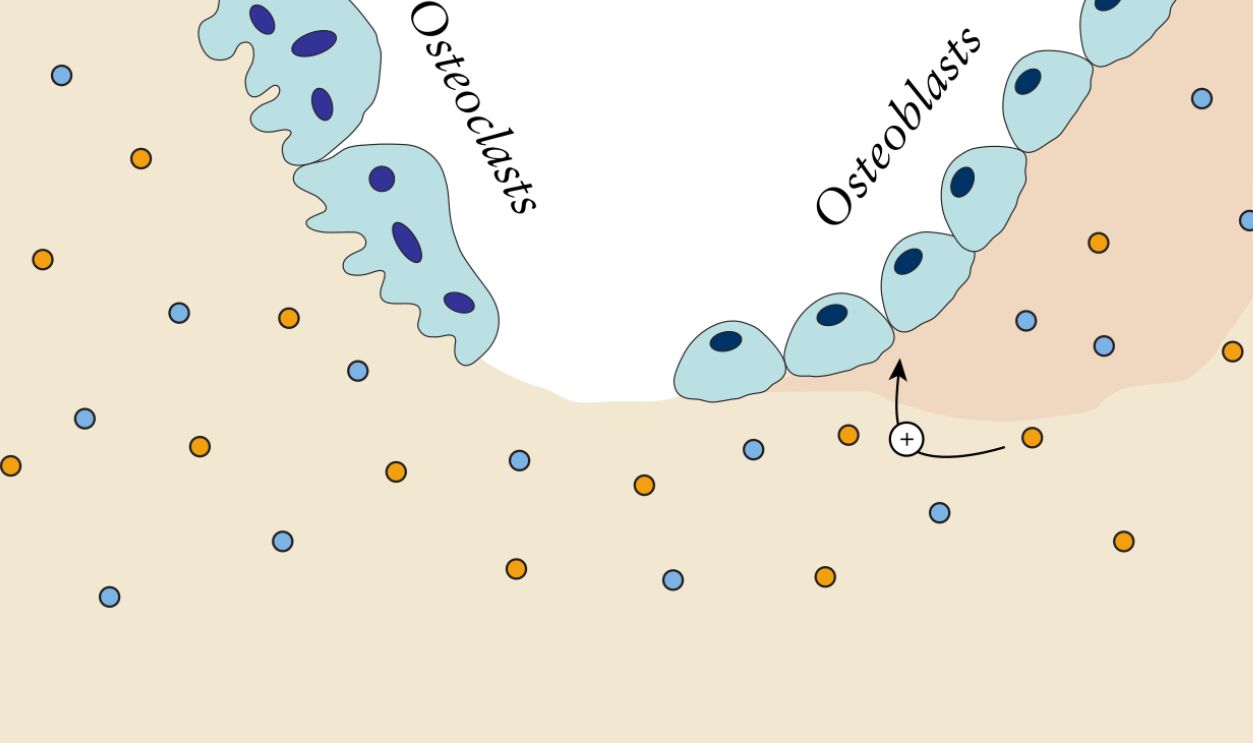

Anatomical Knowledge

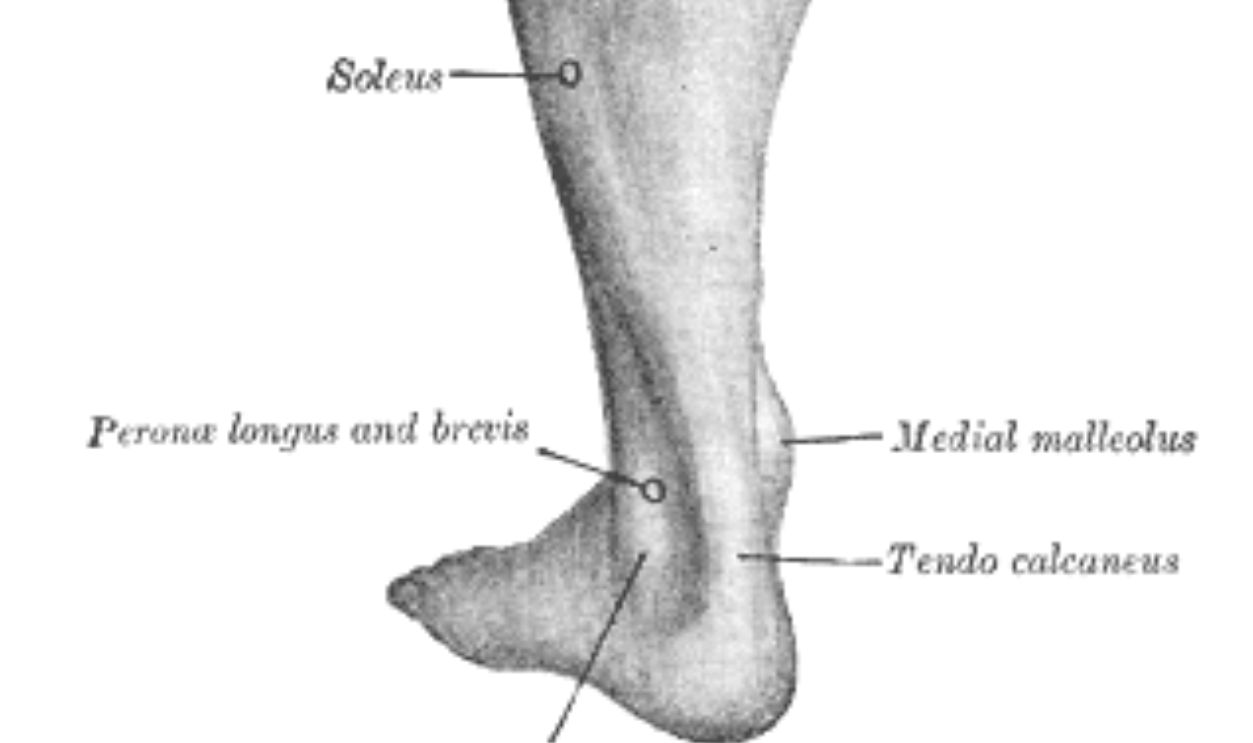

The surgeons had to understand exactly what lay beneath TB1's skin. They needed to identify and isolate the anterior tibial artery, posterior tibial artery, and peroneal artery to prevent the child from bleeding out in minutes. The fibular and tibial nerves required careful exposure and cutting to avoid unnecessary trauma.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Vandyke Carter, Wikimedia Commons

Blood Loss

Fatal hemorrhaging was the primary killer in amputations until the 1800s; even during the American Civil War, patients regularly bled to death on operating tables. TB1's surgeons somehow prevented this catastrophe without modern clamps, tourniquets, or cauterization tools.

Jenny O'Donnell, Wikimedia Commons

Jenny O'Donnell, Wikimedia Commons

Infection Control

Until Joseph Lister discovered antiseptics in the 1870s, surgical infection killed more patients than the procedures themselves. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, amputation mortality reached a staggering 76% despite chloroform anesthesia. TB1's survival in tropical Borneo borders on miraculous without modern sterilization.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Medicinal Plants

Borneo hosts one of Earth's richest botanical pharmacies with over 15,000 plant species, hundreds possessing medicinal properties documented by the indigenous Dayak tribes. The surgical team had access to natural antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, and hemostatic agents growing within walking distance of Liang Tebo cave.

Dukeabruzzi, Wikimedia Commons

Dukeabruzzi, Wikimedia Commons

Pain Management

The screams alone could have killed TB1 through shock—a child's body shutting down from overwhelming pain trauma during conscious amputation. Yet somehow the patient survived not just the cutting, but also the excruciating bone sawing that would have lasted 30–60 minutes. Borneo's rainforest offers powerful natural sedatives.

T. R. Shankar Raman, Wikimedia Commons

T. R. Shankar Raman, Wikimedia Commons

Clean Amputation

This cutting site on TB1's tibia and fibula shows a precise, oblique angle, not the straight-across hack of battlefield amputations. The sloping cut indicates surgical sophistication: the angled approach crafts a better stump for weight-bearing and reduces tension on healing tissue.

Immediate Aftercare

TB1 required constant monitoring: checking for fever, ensuring the wound didn't reopen, and maintaining fluid intake to prevent dehydration from blood loss. Temperature regulation was critical, with the patient needing warmth without overheating the wound site. Caregivers had to prevent TB1 from moving excessively.

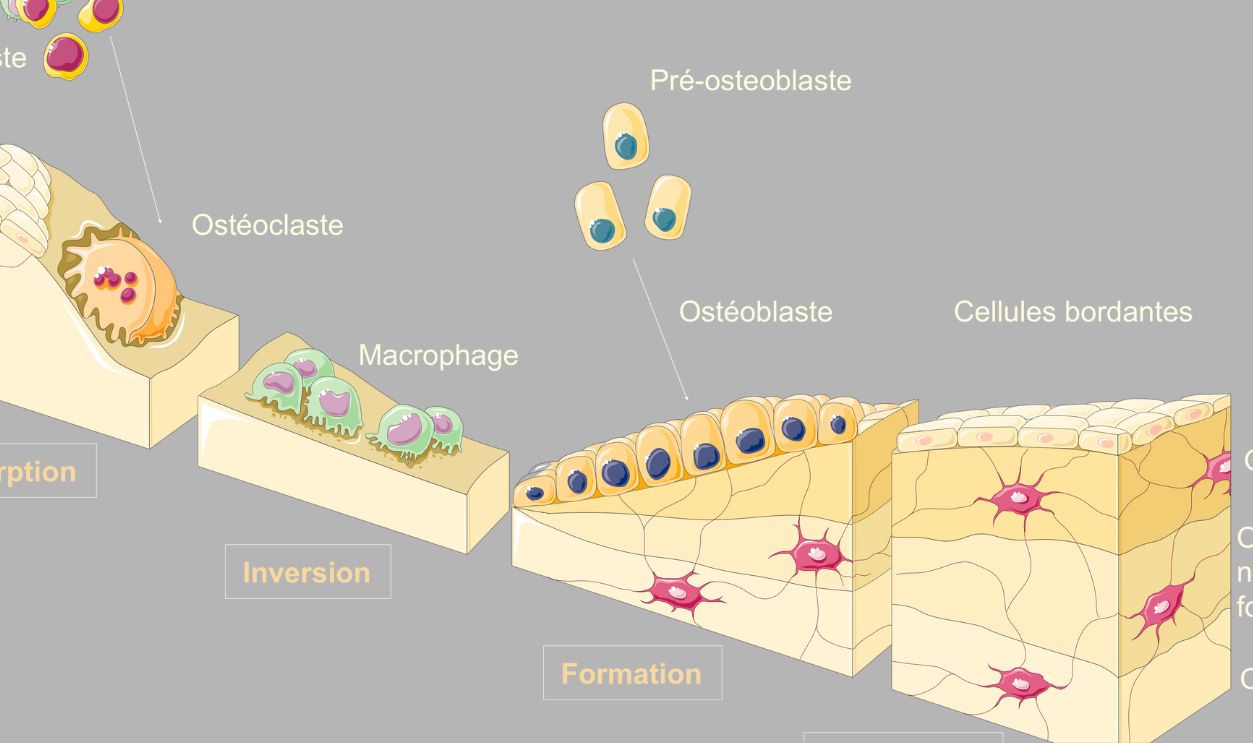

Wound Management

Clinical bone analysis showed zero evidence of post-surgical osteomyelitis, the bone infection that plagued amputation patients until antibiotics arrived in the 1940s. The stump showed healthy bone remodeling with new tissue growth covering the exposed marrow and cortical bone.

Laboratoires Servier, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Laboratoires Servier, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Community Care

TB1's survival proves something profound about Paleolithic society. These weren't brutal, every-person-for-themselves survivalists. Someone carried the immobile child to the water sources. Others pre-chewed food during early recovery when TB1 couldn't move to eat. Hunters shared extra protein needed for healing.

Jean-Pierre Dalbera from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Pierre Dalbera from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

Six-Year Survival

Bone doesn't lie about time. The remodeling patterns on TB1's tibial and fibular stumps told bioarchaeologists exactly how long this individual lived post-surgery. The surviving bone highlighted progressive atrophy from disuse, typical of healed amputations, where the limb portion receives reduced blood flow and bears no weight.

Shandristhe azylean, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Shandristhe azylean, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mountain Mobility

Navigating Borneo's limestone karst terrain on two healthy legs challenges modern hikers—steep cliff faces, slippery river crossings, dense undergrowth, and 165-meter elevation changes from river to cave. TB1 managed this landscape with one leg for years. The archaeological team experienced this difficulty firsthand.

Nur Nafis Naim, Wikimedia Commons

Nur Nafis Naim, Wikimedia Commons

Death Arrived

At approximately age 19 or 20, TB1 died from unknown causes unrelated to the childhood amputation. The healed stump showed no signs of late-stage infection, bone disease, or amputation-related complications. Perhaps illness, accident, or simply life's fragility in the Pleistocene caught up with them.

Mauricio Anton, Wikimedia Commons

Mauricio Anton, Wikimedia Commons

Ceremonial Burial

TB1 wasn't simply discarded or left to decompose. Large limestone markers were deliberately positioned above the skull and arms post-interment, creating a recognizable grave site. The body was placed in a flexed, fetal position within the central chamber of Liang Tebo cave.

Picture taken by R Neil Marshman 12 March 2005 (c), Wikimedia Commons

Picture taken by R Neil Marshman 12 March 2005 (c), Wikimedia Commons

2020 Discovery

Dr Tim Maloney from Griffith University led the Australian-Indonesian team into Liang Tebo's dark chambers in early 2020, searching for artifacts that might illuminate the lives of ancient artists who painted nearby cave walls. Dr India Ella Dilkes-Hall from the University of Western Australia scraped through sediment layers inch by inch.

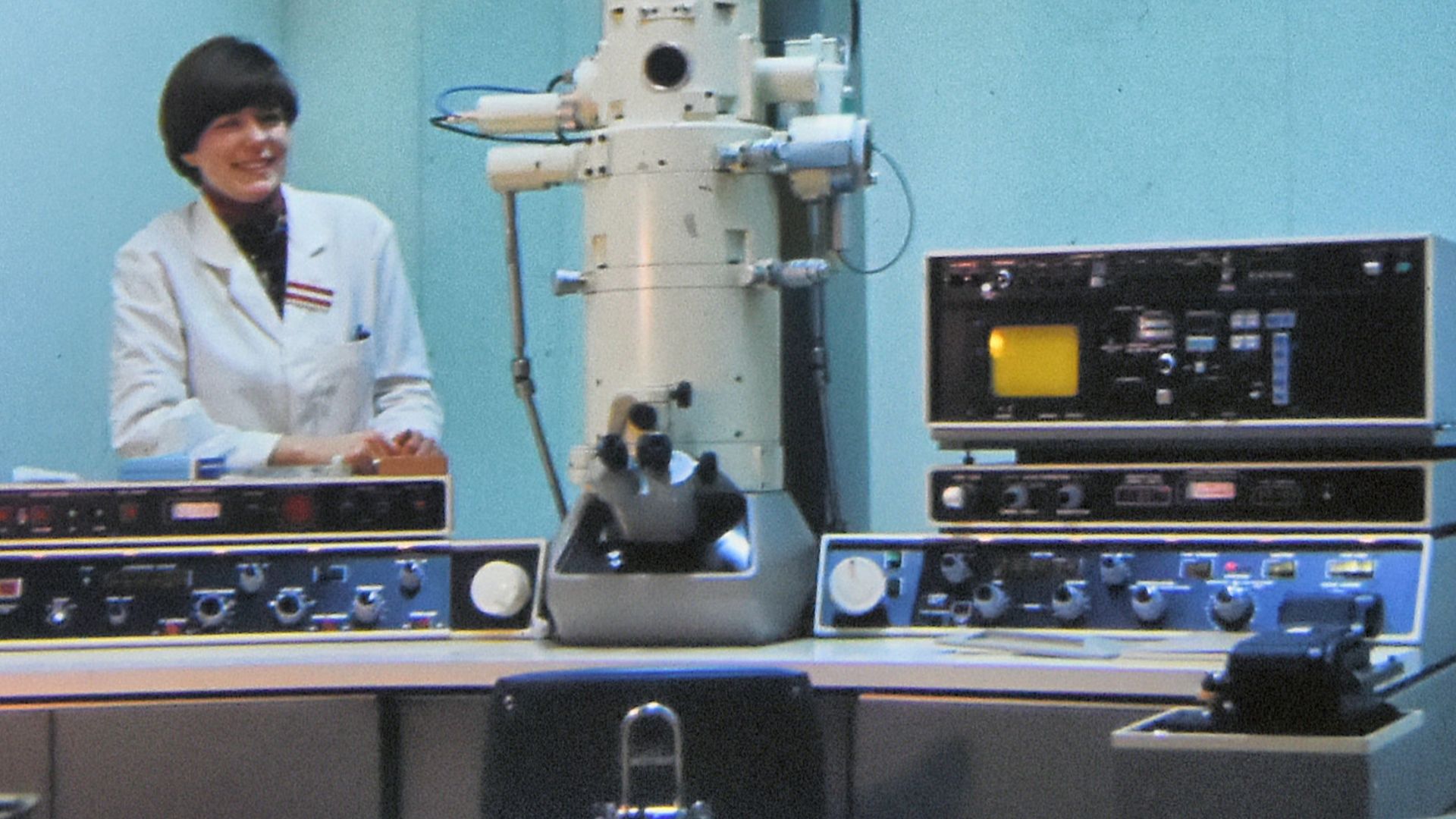

Dating Techniques

Proving the skeleton's age required multiple scientific approaches to eliminate doubt. Associate Professor Renaud Joannes-Boyau from Southern Cross University performed electron spin resonance dating directly on TB1's tooth enamel, measuring radioactive decay of uranium isotopes absorbed during burial, which yielded approximately 31,000 years.

Tadeas Bednarz, Wikimedia Commons

Tadeas Bednarz, Wikimedia Commons

Bone Analysis

Under Dr Vlok's microscope, the amputation site revealed its secrets through telltale bone changes matching modern clinical amputation cases. The tibial and fibular surfaces allegedly showed heterotopic ossification, new bone growth covering the cut ends, a healing signature impossible to fake.

Dr Graham Beards, Wikimedia Commons

Dr Graham Beards, Wikimedia Commons

History Rewritten

This single skeleton demolished 24,000 years of assumed medical history overnight when the Nature journal publication hit September 7, 2022. Professor Charlotte Roberts from Durham University, a bioarchaeologist and former nurse, called it the "dawn of surgery"—evidence that challenged everything scholars believed about prehistoric medical capabilities.