Rock Solid Mystery

Deep in Turkey lies a city that challenges almost everything we think we know about ancient technology. The Hittites left behind stone work that continues to baffle experts centuries later.

Ancient Capital

Hattusa served as the mighty capital of the Hittite Empire during the Bronze Age, roughly from 1600 to 1200 BCE. This sprawling city covered 440 acres at its peak and housed around 10,000 people. It sits within a dramatic loop of the Kizilirmak River.

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Hittite Empire

The Hittites built one of antiquity's most powerful empires, controlling several territories across Anatolia and beyond. King Labarna moved the capital from Nesa to Hattusa around 1650 BCE, taking the name Hattusili. The empire wielded bronze weapons, developed laws, and maintained diplomatic relations with Egypt.

Oliver Kloss, Wikimedia Commons

Oliver Kloss, Wikimedia Commons

Hittite Empire (Cont.)

This led him towards eventually signing history's first recorded peace treaty after the Battle of Kadesh. Although the fight itself ended inconclusively, with magnificent losses on both sides and no clear winner, it marked the culmination of a prolonged period of conflict over territorial control.

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Wikimedia Commons

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Wikimedia Commons

Site Discovery

French archaeologist Charles Texier stumbled upon the ruins of Hattusa in 1834 during an exploratory mission to Turkey. He discovered monumental stone structures near the village of Bogazkoy and created the first topographical measurements and site plans. Texier's initial drawings revealed massive walls, gates, and mysterious stone blocks.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Excavation Begins

Systematic excavations then commenced in the early 20th century under Hugo Winckler and the German Oriental Society. Winckler's team unearthed many cuneiform tablets starting in 1906, confirming the location’s identity as the Hittite capital. These clay archives contained legal codes, diplomatic correspondence, and religious texts.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

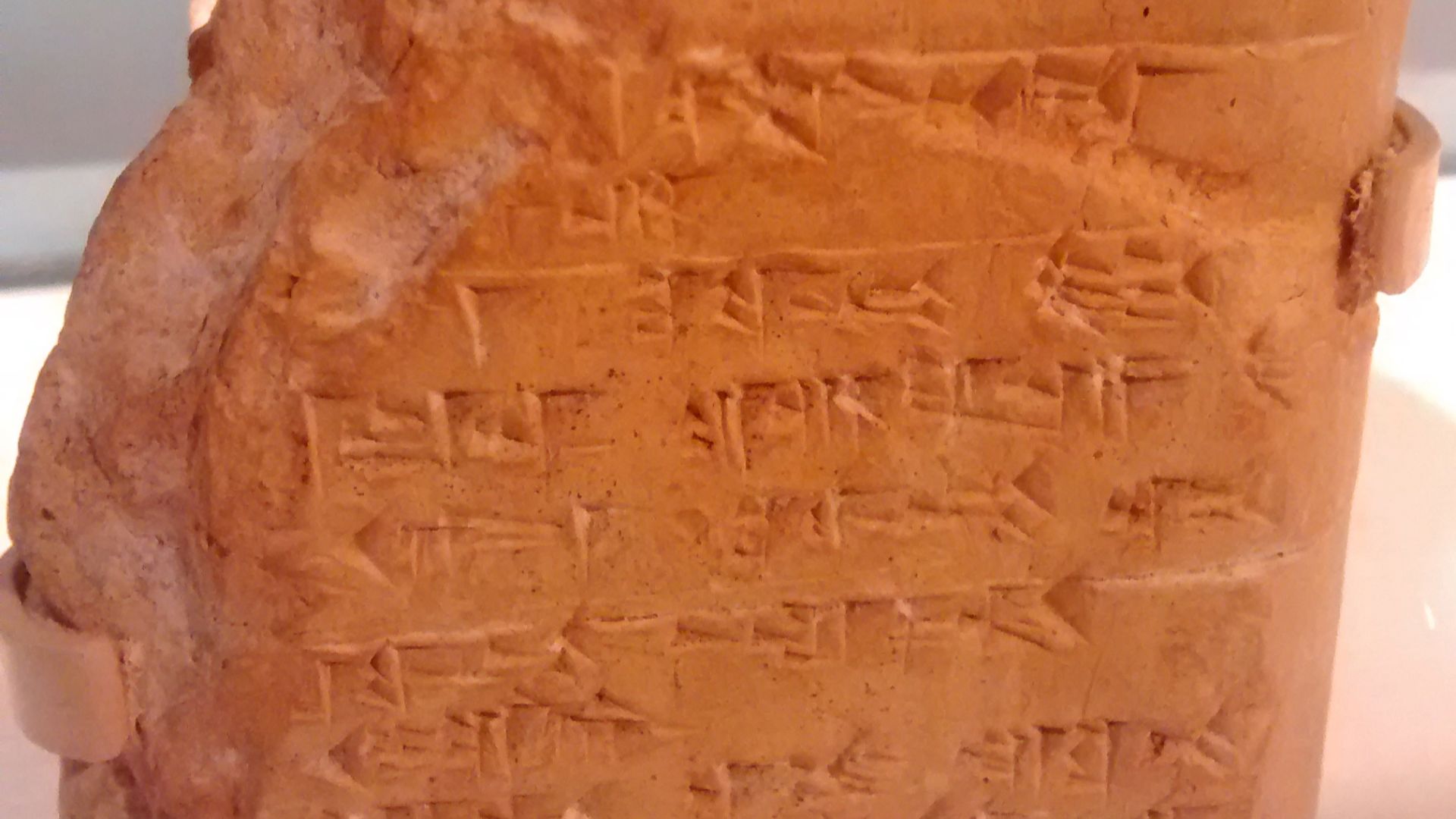

Cuneiform Tablets

Numbering around 30,000, such clay tablets were found in the royal archives of the Hittite town and date primarily to the New Kingdom period of the Hittite Empire (circa 1650–1200 BCE). The majority of the tablets are written in Hittite, the oldest attested Indo-European language.

Mx. Granger, Wikimedia Commons

Mx. Granger, Wikimedia Commons

Massive Walls

Hattusa's fortifications stretched an impressive 6.6 kilometers around the city, featuring inner and outer stone skins with rubble fill between them. The walls reached a total thickness of 8 meters and included elaborate gateways decorated with carved lions, sphinxes, and warriors.

Murat Özsoy 1958, Wikimedia Commons

Murat Özsoy 1958, Wikimedia Commons

Fortifications

These defensive structures demonstrated fantastic Bronze Age engineering, requiring coordinated labor forces and detailed planning to construct such monumental architecture. Additionally, the fortifications protected Hattusa from rival powers and nomadic raiders, ensuring the security of this place and its inhabitants.

Carole Raddato from Frankfurt, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from Frankfurt, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Sphinx Gate

This town’s southern entrance features large stone sphinxes that originally guarded its most important gateway. German archaeologists removed these monuments in 1917 for restoration, with one eventually returning to Turkey in 1924. The sphinxes showcase intricate carving techniques achievable with Bronze Age tools.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Stone Construction

The city's builders utilized huge limestone and granite blocks, some weighing several tons, and fitted them together with good precision. Many sections originally used no mortar, relying instead on careful stone cutting and placement. Archaeological evidence shows the Hittites employed copper and bronze tools.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Lever Systems

They also made use of wooden levers and sand abrasives to shape these enormous blocks into their final positions. Wooden levers were essential for moving and adjusting heavy stones. They could easily lift, tilt, or shift bricks with significantly less effort.

Wikids.ru М., Wikimedia Commons

Wikids.ru М., Wikimedia Commons

Cylindrical Holes

Many round holes appear throughout Hattusa's stone blocks, be it small depressions or deep cylindrical cavities. Alternative researchers have counted between 50 and 100 such holes in different site areas. These openings show weathering and age, appearing on both limestone and harder granite surfaces.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Cylindrical Holes (Cont.)

They further exhibit a fascinating range of diameters and depths, from small, shallow indentations to deeper, more uniform cylindrical bores. In some cases, the holes appear to be arranged in linear or geometric patterns, sparking curiosity and debate among scientists and visitors alike.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Drilling Claims

Some researchers also argue that these cylindrical holes resemble modern core drilling marks, suggesting advanced technology existed in antiquity. They point to the holes' regular shapes and internal weathering as evidence of highly developed drilling equipment. Proponents claim such precision would be impossible with Bronze Age tools.

Murat Özsoy 1958, Wikimedia Commons

Murat Özsoy 1958, Wikimedia Commons

Precision Cuts

The precision cuts found at Hattusa are among the remarkable features of the site’s monumental architecture, reflecting the advanced stonemasonry skills of the Hittites. These cuts allowed large stone blocks to fit tightly together, contributing to the durability and imposing appearance of city walls, temples, and gates.

Granite Transport

Those huge granite blocks scattered throughout Hattusa originated from quarries located over 150 kilometers away, possibly near ancient Ephesus. Moving these multi-ton stones across Anatolia's rugged terrain would have required incredible logistical coordination. Each block represents weeks of transport using sledges, wooden rollers, and hundreds of workers.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Green Stone

A mysterious polished green boulder in Hattusa’s Great Temple complex is known as the Hattusa Green Stone. This block (roughly 1000kg), crafted from nephrite (a form of jade), is unique at the site and stands out for both its material and enigmatic history.

Murat Özsoy 1958, Wikimedia Commons

Murat Özsoy 1958, Wikimedia Commons

Green Stone (Cont.)

The original function of the Green Stone remains unknown. But researchers speculate it may have served as a base for a statue, a throne for ceremonial purposes, or possibly as an altar. However, none of the sacred stones described in Hittite texts are explicitly identified as green.

Multiple Phases

Archaeological layers highlight distinct construction periods with dramatically different building styles and stone-working quality. Earlier megalithic work shows superior precision compared to later Hittite-era additions. This suggests either the evolution of techniques over time or the establishment of completely different builder cultures occupying the site.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/travellingrunes/, Wikimedia Commons

https://www.flickr.com/photos/travellingrunes/, Wikimedia Commons

Archaeological Tools

Excavations at Hattusa have yielded a wealth of actual Bronze Age tools and implements, offering direct evidence of the construction technologies used by the ancient Hittites. Researchers have uncovered copper chisels, bronze saws, and stone hammers—tools that were essential for quarrying and shaping.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme, Philippa Walton, 2007-06-21 14:35:23, Wikimedia Commons

The Portable Antiquities Scheme, Philippa Walton, 2007-06-21 14:35:23, Wikimedia Commons

Archaeological Tools (Cont.)

These implements demonstrate that the Hittite builders relied on the best available technologies of their time. A particularly notable finding was made during the 1990s, when archaeologists unearthed an Iron Age saw dating back approximately 2,250 years at Hattusa.

Iron Age Saw

Belonging to the Galatian period, it was spotted at the Great Fortress. The saw measures about 20 centimeters in length. Although only the iron blade survives, holes on either side indicate it was initially fitted with a semicircular wooden handle.

Iron Age Saw (Cont.)

The teeth of the saw are strikingly similar to those found on modern tools. Professor Andreas Schachner, head of the excavation team, emphasized the rarity of such a find in Anatolia from this period and noted that it is the first of its kind to be discovered in the region.

Modern Research

Ongoing excavations at Hattusa continue to reveal new insights into Hittite construction techniques and daily life. Recent discoveries include workshop areas, tool caches, and partially finished stone blocks that illuminate ancient working methods. Ground-penetrating radar maps also show subsurface structures.

Carole Raddato from Frankfurt, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from Frankfurt, Germany, Wikimedia Commons