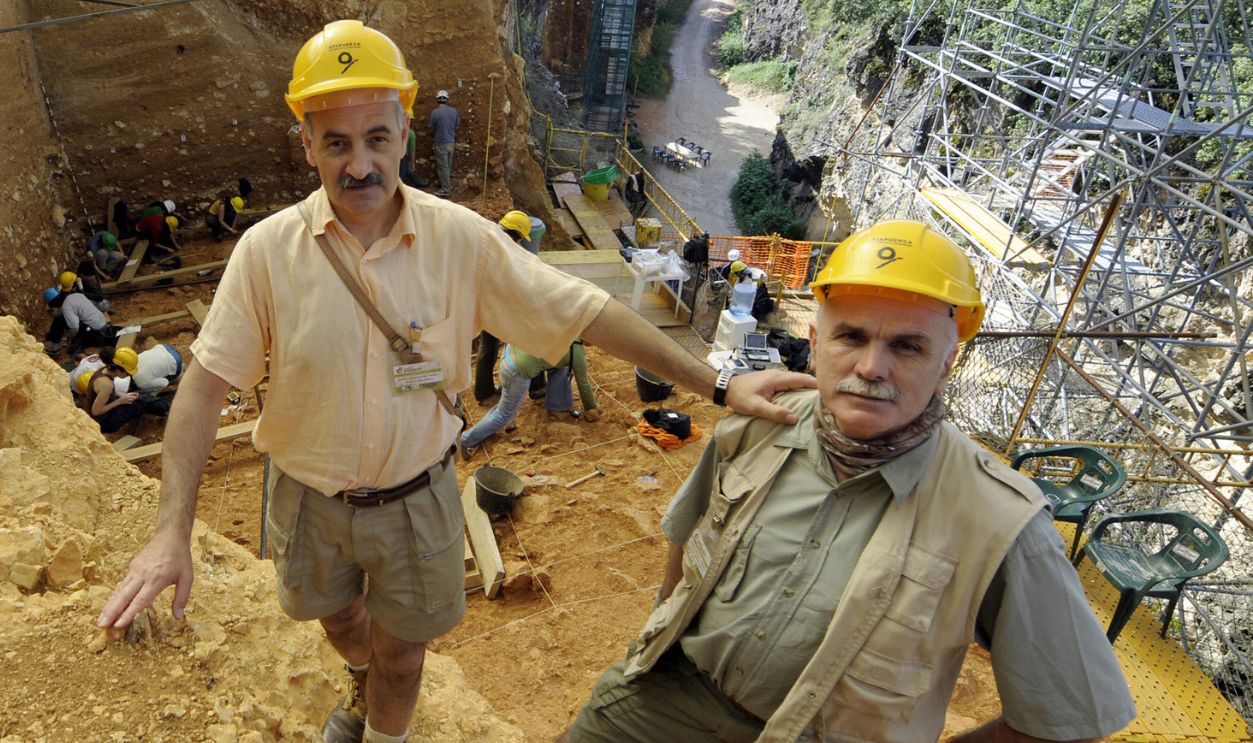

PHILIPPE DESMAZES, Getty Images

PHILIPPE DESMAZES, Getty Images

Beneath the hills of northern Spain lies a site that continues to reshape our picture of early human life. At Atapuerca’s Gran Dolina cave, researchers of IPHES-CERCA recently uncovered a tiny cervical vertebra—just over an inch long—that had been buried for nearly 850,000 years. It belonged to a child no older than four, and the sharp cut marks etched across its surface revealed something unsettling: the child had been deliberately decapitated.

This discovery adds powerful confirmation to a long-debated idea that early cannibalism in Western Europe may have been both systematic and tied to survival pressures.

Unearthing The Story Beneath The Stone

Gran Dolina has become central to understanding early human evolution. The TD6 layer, discovered in 1994, has yielded more than 1,000 stone tools and about 170 fossil fragments belonging to Homo antecessor, a species that lived between 1.2 million and 800,000 years ago.

Standing around five feet tall, these early humans relied on flint flakes and simple hand axes to butcher animals—and, based on the evidence, occasionally each other.

Over a decade of excavation, scientists have uncovered ten sets of Homo antecessor remains at TD6, many showing signs of intentional processing. Bones were split open for nutrient-rich marrow, and soft tissue was removed using the same techniques applied to prey animals.

This was clearly visible as when the discovered child’s vertebra was studied under magnification, its cuts matched those found on deer and bison in the same sediment layer. Such precision makes accidental damage unlikely.

Microscopic analysis further supports this to show straight-lined cuts with internal grooves—clear indicators of stone tools rather than predator teeth or natural abrasion.

These findings continue to raise key questions. Were early humans responding to environmental hardship, or could these actions have held social or ritual meaning? While both remain possible, many researchers lean toward survival-based behavior during a time when food sources fluctuated and competition for resources was intense.

Nanosanchez, Wikimedia Commons

Nanosanchez, Wikimedia Commons

Reading What The Bones Reveal

Inside the cave, what stands out is how long the area has been used. Excavations show that TD6 wasn’t shaped by a single moment. Instead, different groups returned over long periods, leaving behind fresh tools and new layers of bone. This repeated activity helps explain why human and animal remains appear side by side.

Moreover, the mix also shows that Gran Dolina served as a temporary activity area rather than a permanent home. Each visit added another thin layer of debris—stone fragments from toolmaking, broken bones from meals, and traces of brief occupations. All of this helps researchers understand how early humans moved through the cave and how often they came back to use the same spaces.

Mario Modesto Mata, Wikimedia Commons

Mario Modesto Mata, Wikimedia Commons

Inferences Drawn From The Discovery

Discoveries like this vertebra remind us that early human evolution was shaped by conditions far harsher than anything faced today. These findings challenge modern assumptions about empathy or moral codes, emphasizing instead a time when survival dictated action. The ability to process food efficiently and adapt quickly laid the groundwork for the cognitive development seen in later human species.

Similar evidence has surfaced at other sites, such as Moula-Guercy in France, where Neanderthal bones from 100,000 years ago show cut marks consistent with butchery. Such discoveries highlight that cannibalism was not a rare anomaly but a recurring response to scarcity across different human groups.

Today, the child’s tiny vertebra is preserved in a laboratory in Burgos to provide one of the clearest glimpses into daily life in Early Pleistocene Europe. Its cut marks confirm that Homo antecessor engaged in systematic butchery, likely tied to group needs and survival strategies rather than isolated aggression. The find also highlights the practical, rather than sentimental, decision-making that shaped early human responses to harsh environments.

Mario Modesto Mata, Wikimedia Commons

Mario Modesto Mata, Wikimedia Commons