Are They Really Extinct?

The Taíno were once the dominant indigenous group in the Caribbean—until they met Christopher Columbus. This encounter ushered in a time of devastation for the Taíno, and within 60 years, they were declared to be extinct.

That was a lie.

Some Taíno communities can still be found in Cuba and the Dominican Republic. And in Puerto Rico, DNA science has helped many people prove and reclaim their Taíno heritage.

So who were the Taino? And where did the lie about their extinction come from? Let's find out.

Where Did They Live?

Historically, the Taíno were one of the largest Indigenous groups in the Caribbean.

They lived in Cuba, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, the Bahamas, and Puerto Rico.

Still Here

While it was thought that the Taíno went extinct, their descendants are still alive and well today.

In recent decades, many Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans have claimed Taíno identity—and the science backs them up.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

DNA Evidence

Mitochondrial DNA has proven that many people are descended from ancient Taíno via direct female ancestors.

Now, some communities have been able to prove an unbroken line of cultural traditions that have been passed down from their Taíno ancestors.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Embracing Their Culture

Other communities are more revivalist, since they have Taíno ancestors but didn’t have knowledge of their culture passed down the generations.

In these communities, people incorporate aspects of Taíno culture in their everyday lives to honor their heritage.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Their Origins

According to the Taíno creation story, the Taíno people came from caves in a sacred mountain.

The mountain is on the island of Hispaniola and from there, they spread to other islands in the Caribbean.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Their Origins (cont’d)

There may be some truth to this origin story. According to DNA studies, it’s most likely that the first Taíno traveled from the north-eastern coast of South America to the Caribbean islands via canoes.

This happened about 2,500 years ago, and the Taíno soon took over from the early inhabitants of the islands, most likely from disease or warfare.

Scan by NYPL, Wikimedia Commons

Scan by NYPL, Wikimedia Commons

Taíno Society

Historically, there were two main classes in Taíno society: The “naborias”, who were commoners, and the “nitaínos” who were nobles.

The nitaínos were usually warriors or members of the chief’s family.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Taíno Society (cont’d)

The nitaínos were advisers and overseers in the community. They would control the day-to-day operations in the community, and also assigned and supervised work for the naborias.

The naborios were the low-class workers in Taíno society.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Cacique

Communities were led by a male chief called a “cacique”. The Cacique is a nitaínos who inherits his role from his mother’s familial line.

To distinguish himself from the rest of the community, the Cacique lived in a square-shaped house, while the other villagers lived in circular homes.

At gatherings, the Cacique sat on a stool to be physically higher than the other Taíno.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Cacique (cont’d)

One Cacique could be responsible for many villages, and the number of villages he governed was a symbol of his power.

It was common for the Cacique to have a wife and family in each of his villages. More family ties equaled more alliances, which was useful to defend against attack.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Guanin Pendant

To show his elite status, the Cacique wore a large gold pendant called a “guanín”.

The guanin represented the first Cacique, who was named Anacacuya, meaning “central spirit”.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

They Were Matrilineal

Although communities were led by a male chief, Taíno society was matrilineal.

The way they viewed kinship, ancestry and inheritance were all based on who one’s female relatives. For example, the Cacique used to be succeeded by the oldest son of his oldest sister.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Taíno Women

Since Taíno society was matrilineal, women had a lot of power in the community. They could possess their own land, make important decisions within the community, and those in the noble caste could assign roles to other villagers.

Women often lived in their own villages with their children, while the men lived in a village nearby. While this signified women’s importance to the community, it also put them at risk.

Dangers To Taíno Women

Conflicts between the Taíno and the Caribs, another indigenous group, were a frequent occurrence in some parts of the Caribbean. And when the Caribs came for war, they also came for Taíno women.

Sadly, When Christopher Columbus met the Taíno, he continued this brutal tradition of abduction, though on a much broader scale.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Bohíques

The Caique would often take advice from sacred healers called “bohíques”. The bohíques were revered for their healing powers and the ability to communicate with spirits and deities.

As such, people often had to consult with a bohíque and gain their permission to carry out certain important tasks.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Bohíques (cont’d)

In addition to advising people, the bohíque's main role was to petition the gods on behalf of the people.

If the gods were angry, it was the bohíque’s job to appease them. If people were sick, they asked for the gods to help heal them.

Before communicating with the gods, it was customary for the bohíque to perform a purification ritual, such as fasting for several days or inhaling sacred nicotine.

Taíno Gods

In Taíno spirituality, spirits called “zemis” are worshipped. The two most important zemis are Atabey, zemi of the moon, fertility, and fresh water, and her son Yúcahu.

Yúcahu means “White Yuca”, and he was believed to be the spirit of cassava, or yuca, and the ocean.

Taíno Gods (cont’d)

While Atabey was nurturing, her other form, Guabancex was far more fearsome. She was the zemi of natural disasters, especially storms.

Her twin sons Guataubá and Guataubá were responsible for making hurricane winds and floodwaters.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

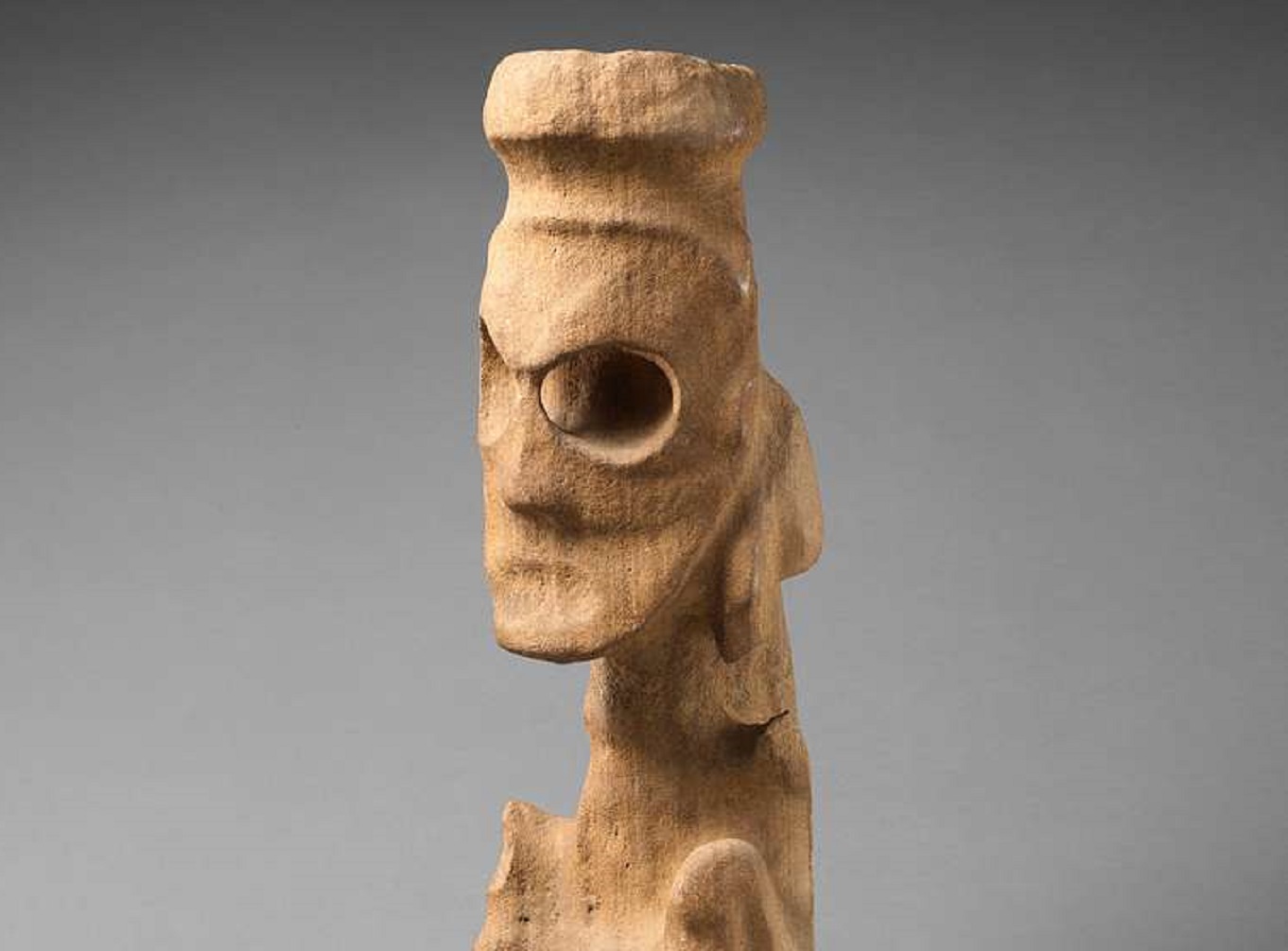

Physical Zemis

“Zemi” also refers to objects or drawings that represented spirits. Most of these totems were carved from wood, but stone, bone, shells, and cotton were also used to make zemis.

Zemi petroglyphs have also been found in ball courts, caves, and on rocks near streams.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Picryl

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Picryl

Physical Zemis (cont’d)

Some zemis were made with built-in trays. It is believed that these trays were to hold purifying herbs that were burnt during rituals.

They may also have been used to hold a type of snuff called “cohoba”, which induced hallucinations during rituals.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Picryl

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Picryl

The Underworld

The Taíno underworld is called Coaybay, and they believe that the souls of the departed, called “jupias”, rest there during the day. At night, the jupias turn into bats and eat guava fruit.

The zemi who rules the Coaybay is called Maquetaurie Guayaba. A dog-shaped zemi named Opiyelguabirán helps her watch over the departed.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Taíno Uncles

Matrilineal ties are also evident in a Taíno marriage custom. Traditionally, the newlyweds would live with the bride’s maternal uncle.

He was a primary father figure to his niece’s children since he would be the one to teach the young boys about Taíno society and traditions from his family’s clan.

Taíno Marriage Traditions

Historically, most Taíno were monogamous, though there were some who were polygamous. In that case, a man or woman could have up to three partners.

The Caciques also usually practice polygamy, with some of the more powerful leaders having up to 20 wives.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

What Did They Eat?

Taíno women were excellent farmers. Yucca, also known as cassava, was their staple crop. Other common crops include corn, beans, peppers, and pineapples.

While the women farmed, men would hunt and fish. They made fishing nets out of cotton and palm wood and dipped their arrowheads in poison.

What Did They Hunt?

Though there were no large animals in the Caribbean, the Taíno were proficient hunters. Lizards, turtles, and birds were common prey.

Hutias, a large rodent, were another staple, as were manatees.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Their Clothes

Historically, Taíno did not wear much in the way of clothing. After they got married, women would wear a cotton apron called a “nagua”.

Women would also sometimes wear gold jewelry and shells or body paint.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Their Villages

Taíno villages were called “yucayeques”. The center of the village was usually a communal plaza, which was used for events like festivals, sacred rituals, and games.

The plazas could be built in many shapes—some were oval or elongated, while others were rectangular.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Taíno Houses

Taíno houses were built around the central plaza. Called “bohios’, these homes were large and circular, and built with woven straw, palm leaves, and wooden poles.

The Cacique’s home was rectangular and had wooden porches.

Michal Zalewski, CC BY-SA 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

Michal Zalewski, CC BY-SA 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

Ceremonial Games

The central plaza of a Taíno village often had a rectangular ball court where they played a ceremonial game called “batey”.

Batey was played with a rubber ball and was similar to modern volleyball as points were gained if a player failed to return a pass.

However, batey wasn’t far from your average ball game.

Alessandro Cai (OliverZena), Wikimedia Commons

Alessandro Cai (OliverZena), Wikimedia Commons

Batey

In batey, players were not allowed to touch the ball with their hands. People could strike the ball with their head, shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, or butt.

Players would get a fault if they let the ball touch the ground or threw it out of bounds. The game would go one until one side reached a predetermined number of points.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Batey (cont’d)

Batey teams were made up of 10 to 30 people. Most teams were all men, but women sometimes played, too.

When that was the case, teams could be co-ed teams or gender specific. Some games even pitted married women against unwed virgins.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Purpose Of Batey

Most of what we know about batey comes from Spanish explorers’ records.

It seems like the game was used as a way for tribes to resolve disagreements without going into all-out war. Chiefs and players would often make wagers on who would win.

Taíno Warfare

During times of war, the Taíno would decorate their faces with battle paint, to appear more fearsome to their enemies.

They would also perform ceremonies where the warriors called upon their ancestors and ingested herbal substances to make them stronger.

The traditional weapon of choice for a Taíno warrior was a wooden club called a “macana”.

Their Language

The Taíno spoke an Arawakan language and used petroglyphs, or rock carvings, as a form of writing system.

Some ancient Taíno words have influenced modern words. For example, "barbacoa" for “barbecue”, "hamaca" meaning “hammock”, and "sabana" meaning “savanna”.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

First Encounters

When Christopher Columbus finally made it to the New World, the Taíno were the first people he met. Sadly, his arrival would mean the destruction of Taíno society.

John Vanderlyn, Wikimedia Commons

John Vanderlyn, Wikimedia Commons

They Welcomed Him

When Columbus reached The Bahamas on October 12, 1492, the Taíno welcomed him to the island.

In his journal, Columbus remarked about how kind and noble they were. He described them as “very gentle” and “without knowledge of what is evil".

Sebastiano del Piombo, Wikimedia Commons

Sebastiano del Piombo, Wikimedia Commons

Tribute

While Columbus’ first encounter with the Taíno seemed to go well, his second voyage in 1493 marked the beginning of a time of horror and sorrow.

Columbus started by demanding tribute from every person over the age of 14.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Tribute (cont’d)

Every three months, each person had to give him a hawk-bell full of gold. If they could not do that, they had to give 25 pounds of cotton.

Anyone who could not give tribute met a cruel fate: the Spaniards would cut off their hands and let them bleed out.

Camille Flammarion, Wikimedia Commons

Camille Flammarion, Wikimedia Commons

Women As Commodities

In addition to tribute, Columbus also enslaved many Taíno. Women became particularly prized, and they could be used as valuable hostages during negotiations with village chiefs.

The Spanish also took the women for more heinous purposes, ushering in a time of systemic assault against Taíno women.

Carlos Nin Gomez, Shutterstock

Carlos Nin Gomez, Shutterstock

Depopulation

In addition to forced labor and enslavement, many Taíno lost their lives to new diseases that were introduced by the Spanish.

Within thirty years of Columbus' arrival, approximately 90% of the Taíno population had died.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Extinct

In 1565, the Taíno were declared extinct. That year, a census showed only 200 Taíno living in the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

By 1802, the records showed no Taínos were left in the Caribbean.

Joshua Shaw, Wikimedia Commons

Joshua Shaw, Wikimedia Commons

Erased From History

While the records showed that the Taíno were extinct, this isn’t exactly true. Some small groups of Taíno hid high in the mountains when the Spaniards came.

Others, upon finally gaining their freedom, were forced to convert to Catholicism, which changed their identification from “Indian” to White, Black, or Mulato on the census.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Still Here

Some DNA studies also showed that Taíno women married African men and lived in secluded Maroon villages.

Despite what they may have written on the census hundreds of years ago, the mixed-raced descendants of these unions can still be found in Jamaica and the Dominican Republic.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Still here (cont’d)

Many people in Cuba and the Domica Republic can trace their direct lineage to historical Taíno communities.

These modern day Taíno have been able to retain much of their cultural tradition, which has been passed down through generations.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Revivalists

There’s a growing revivalist movement for Taíno culture in Puerto Rico.

Many people there identify as Taíno and DNA has proven their heritage. Most are the descendants of Spanish and Taíno unions.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

How Many Are There Today?

In Puerto Rico, about 35,000 people identify as Taíno. However, from mitochondrial DNA evidence, we know that 61% of Puerto Ricans, 33% of Cubans, and 30% of Dominicans have Taíno DNA.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Final Thoughts

The Taíno were not merely a footnote in history, and their vibrant culture is far from extinct.

Despite the tragic consequences of colonization, their legacy endures in the language, art, and traditions that have passed down in remote Taíno communities—and in all the people who have reclaimed their Taíno heritage today.

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Agência de Notícias do Acre, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons