History Buried Deep

Cusco has never been just stone and sky. Beneath the footsteps of tourists and locals alike, something older has been listening. Long-ignored stories now read less like legend and more like unfinished history.

Julia Sumangil, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Julia Sumangil, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Centuries-Old Whispers

For generations, locals in Cusco spoke of secret tunnels snaking beneath their feet, connecting sacred temples to mighty fortresses. These weren't just campfire tales. Spanish chroniclers documented similar accounts as early as 1594. Yet skeptics dismissed them as colonial embellishments or pure folklore, until January 2025.

Tobias Deml, Wikimedia Commons

Tobias Deml, Wikimedia Commons

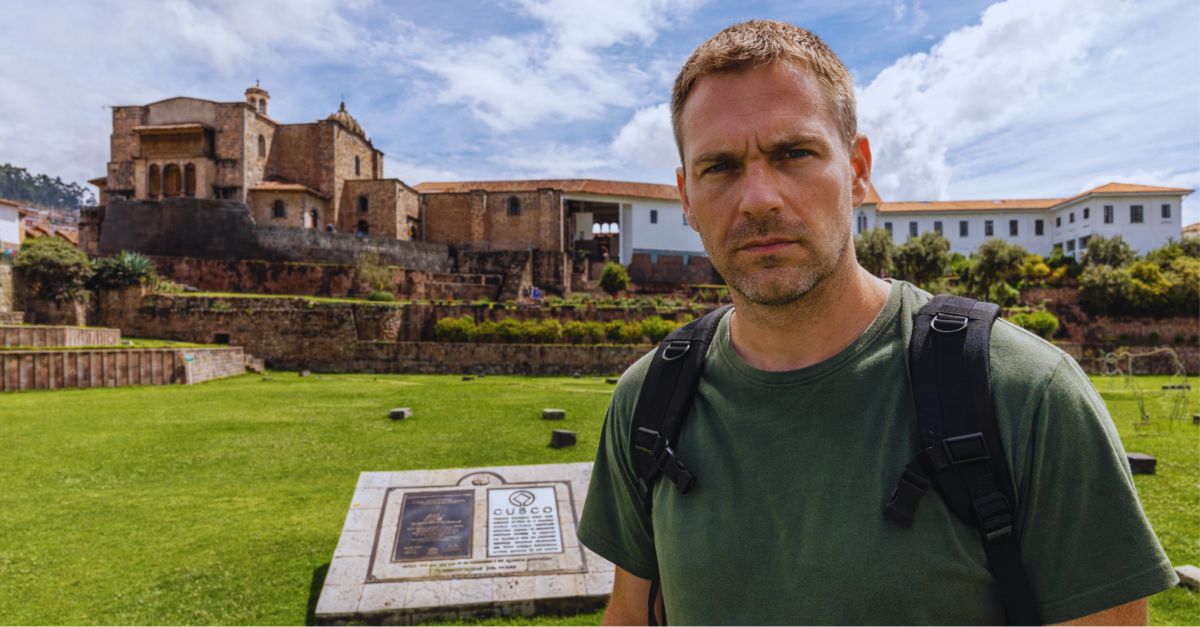

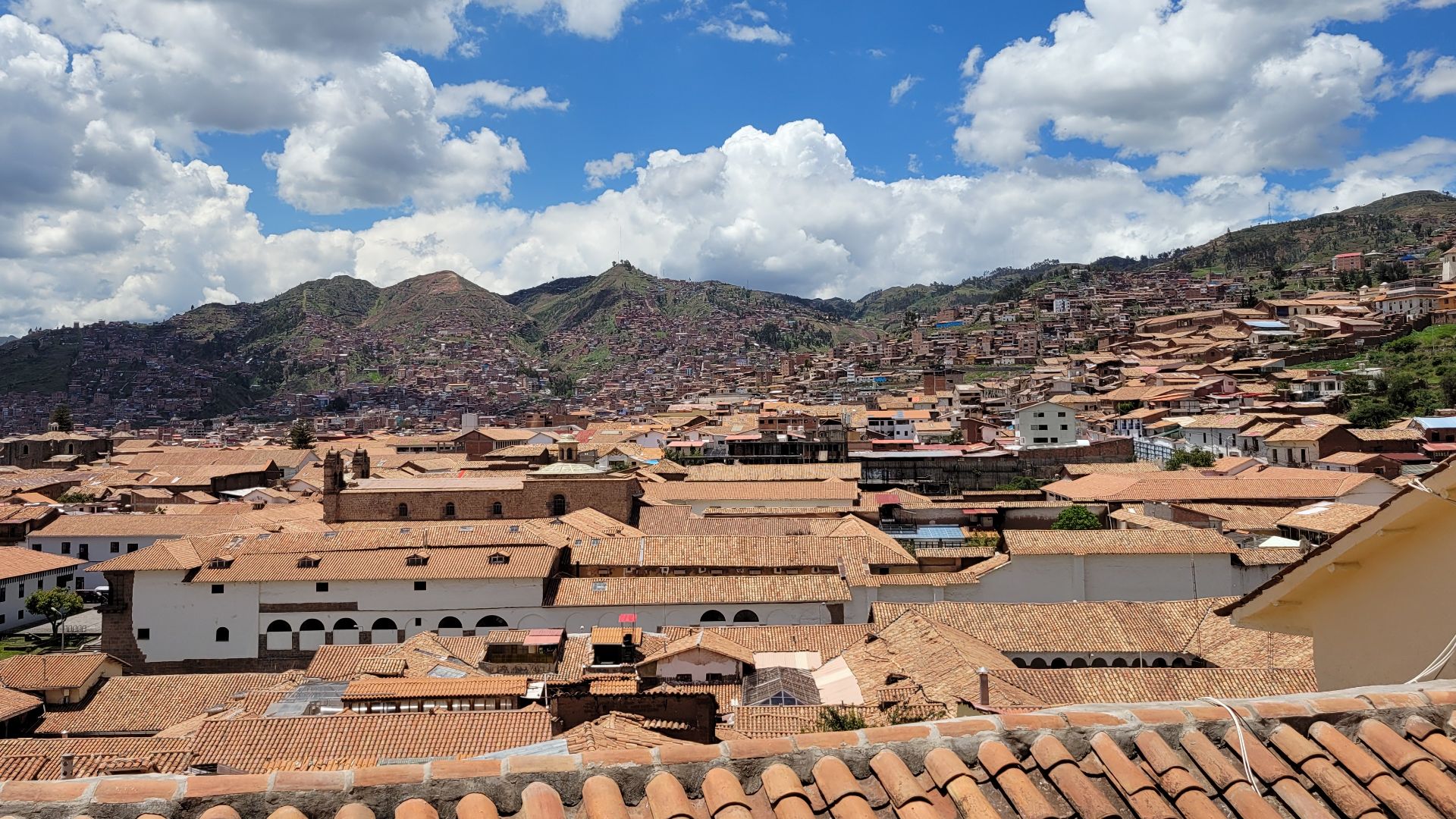

Cusco's Location

Perched at 3,400 meters above sea level in Peru's Andean highlands, Cusco sits in a valley surrounded by towering mountains. This strategic position made it the perfect capital for an empire controlling 12 million people across diverse terrains. The city's geography influenced everything.

gertrudis2010, Wikimedia Commons

gertrudis2010, Wikimedia Commons

Inca Empire

Around the 12th to 16th centuries, the Inca dominated western South America, building one of history's largest pre-Columbian civilizations. Their territory stretched from modern-day Colombia to Chile, encompassing coast, mountains, and jungle. The empire's rapid expansion occurred primarily during the 15th century.

Rowyn flowerdew, Wikimedia Commons

Rowyn flowerdew, Wikimedia Commons

Temple Of Sun

Coricancha, meaning "Golden Enclosure," was the Inca Empire's most sacred religious complex, originally called Inticancha or "House of the Sun”. Emperor Pachacuti rebuilt it around 1438, covering walls with gold sheets that created a dazzling spectacle. The temple housed shrines to multiple deities, including Inti, the sun god.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Sacsayhuaman Fortress

This massive ceremonial complex sits 755 feet above Cusco on the city's northern edge, featuring zigzagging walls stretching over 540 meters with stones weighing up to 125 tons. Construction began under Pachacuti in the 15th century, requiring over 20,000 workers.

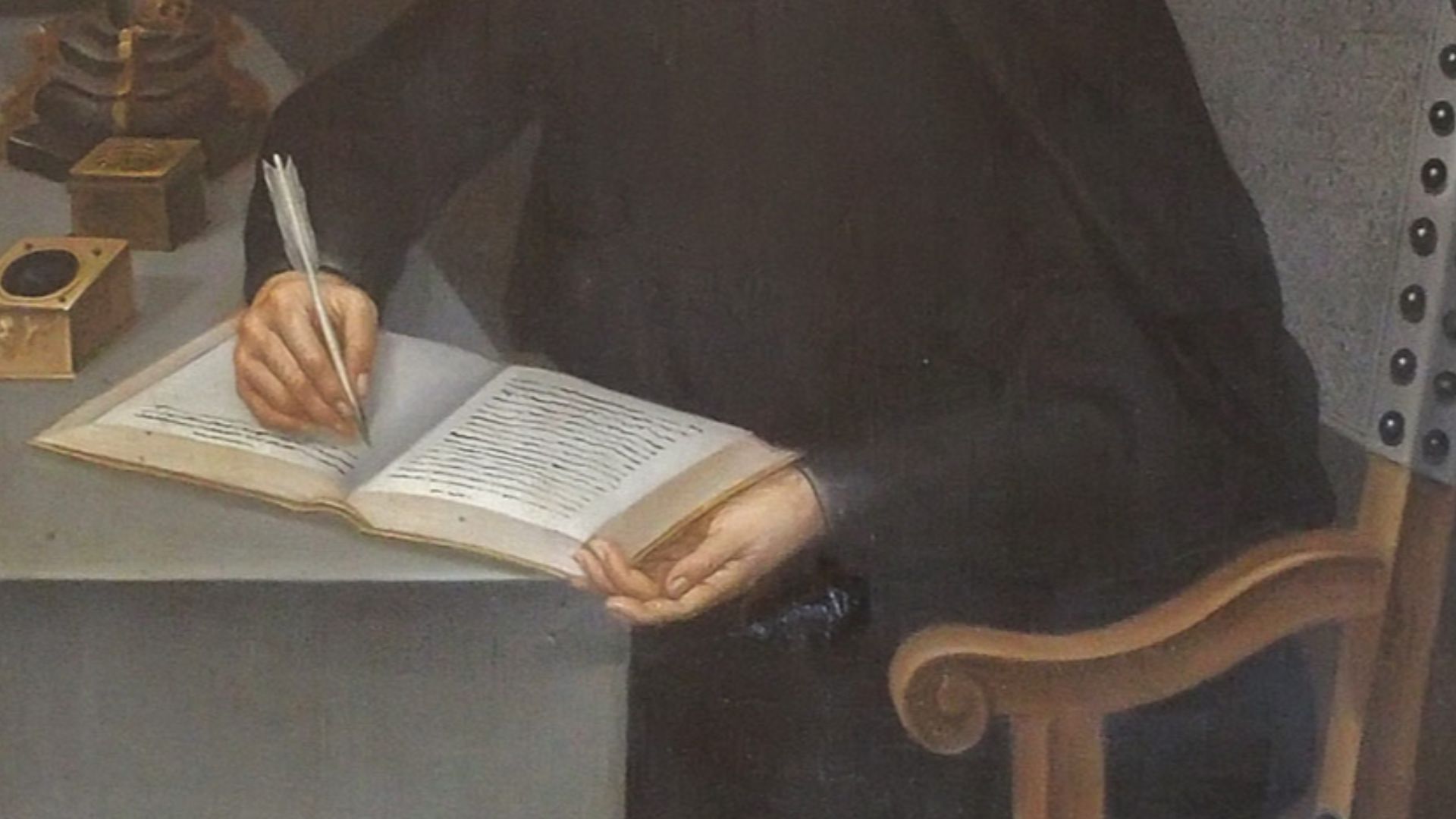

Spanish Chronicles

An anonymous Spanish Jesuit wrote the earliest documented reference in 1594, describing a tunnel connecting the bishop's residence behind Cusco Cathedral to underground passages originating at Coricancha. His account wasn't isolated. Chronicler Anello de Oliva later documented multiple subterranean routes throughout the city.

Luis Fernández García, Wikimedia Commons

Luis Fernández García, Wikimedia Commons

Jesuit Accounts

The Jesuit records proved invaluable because they provided specific geographical markers that survived into modern times. They mentioned tunnels beneath structures that still exist today, such as the Cusco Cathedral, giving archaeologists concrete starting points for investigation.

Local Legends

Cusco residents passed down stories of explorers entering the chincanas and vanishing forever, their ropes found cut at tunnel entrances. Tales spoke of hidden Inca treasure, including a mythical golden corn cob symbolizing agricultural abundance, allegedly concealed before Spanish arrival.

Research Team

The discovery resulted from decades of interdisciplinary collaboration involving archaeologists, civil engineers, geophysicists, and international technology specialists from Swiss company Proceq. The Peruvian Congress even presented a motion recognizing their amazing work and highlighting its national significance.

Jorge Calero

Archaeologist Jorge Antenor Calero Flores, who has published eight books on Andean archaeology and ethnography, directed the multidisciplinary investigation team. A graduate of the Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco, he has spent over 25 years unraveling the chincana mystery.

Ordzonhyd Rudyard Tarco Palomino, Wikimedia Commons

Ordzonhyd Rudyard Tarco Palomino, Wikimedia Commons

Mildred Fernandez

Former director of the Direccion Desconcentrada de Cultura Cusco, archaeologist Mildred Fernandez Palomino, brought extensive expertise in Inca urbanism and architecture to the project. She co-led the Chincana-Sacsayhuaman Project alongside Calero, contributing critical insights into ceremonial infrastructure and spatial organization.

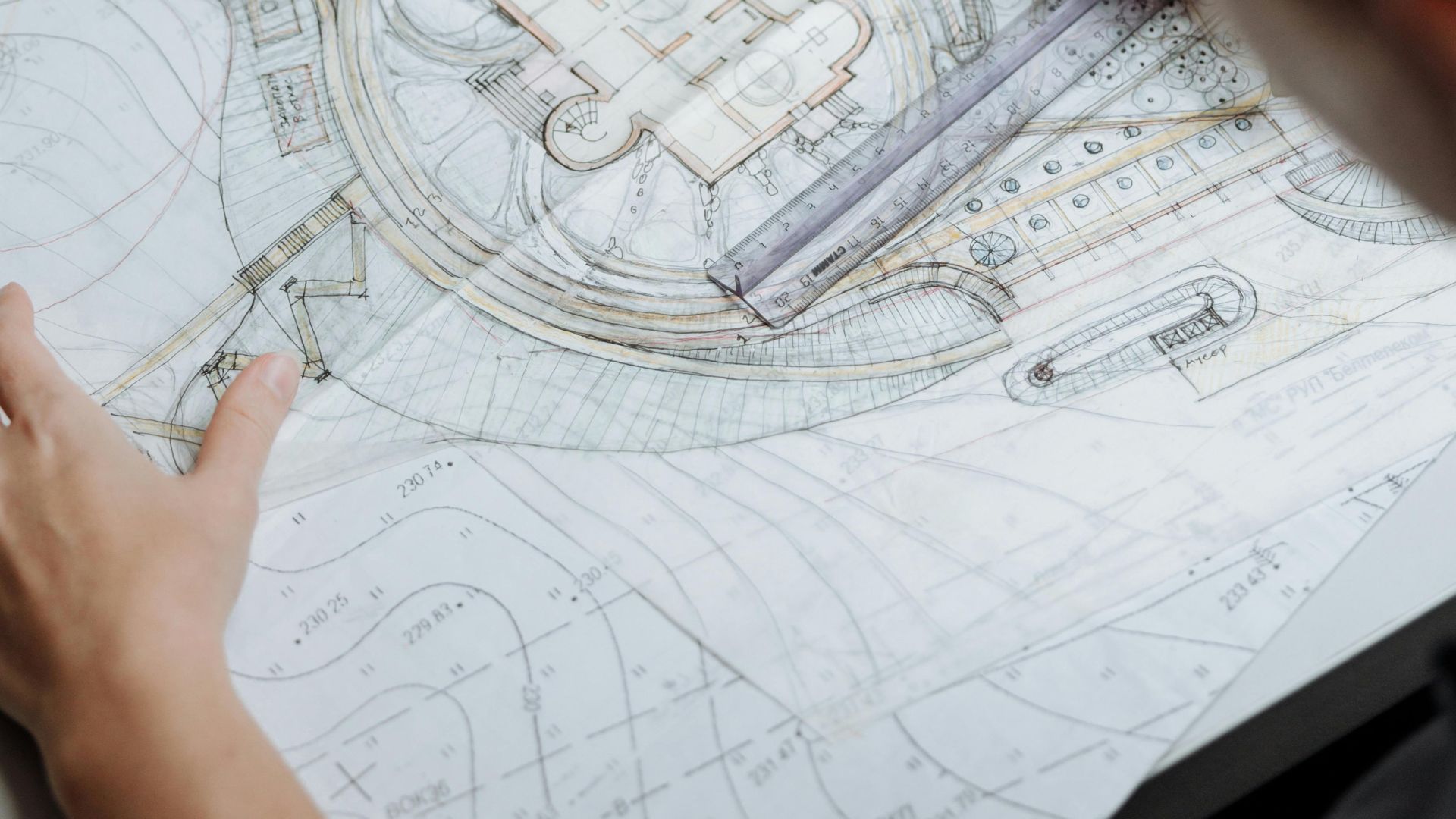

Historical Analysis

The research team's first phase involved exhaustive examination of colonial documents spanning three centuries, from the 1500s through the 1700s. They cross-referenced multiple independent sources, Jesuit records, Spanish chroniclers' accounts, and construction reports, to identify consistent geographical patterns. Researchers overlaid historical descriptions onto modern maps of Cusco.

Acoustic Prospecting

Before deploying expensive radar equipment, the team employed a surprisingly low-tech yet effective method: striking metal plates against the ground every 50 centimeters. They listened carefully to the resulting echoes, identifying areas where deeper resonance indicated potential hollow chambers beneath the surface.

Ground-Penetrating Radar

Georadar technology sent electromagnetic waves deep underground, capturing detailed images of subsurface structures. The GPR scans revealed cavities enclosed by distinctive trapezoidal stone walls—a hallmark signature of Inca construction techniques. Civil engineer Abel Aucca Barcena and geophysicist Ivan Rufino analyzed the complex data patterns.

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

Main Tunnel

The principal corridor stretches an impressive 1,750 meters, connecting Coricancha at Cusco's center to Sacsayhuaman fortress on the northern outskirts. This main passage runs beneath the historic district, following a route that mirrors the ancient Inca street network above ground. The tunnel begins at the Rodadero sector.

Branch Networks

Three additional branches diverge from the main corridor, extending the tunnel system's reach throughout Cusco's ceremonial landscape. One branch leads toward Callispuquio, another connects to the Muyucmarca sector within Sacsayhuaman, and a third runs behind the Church of San Cristobal.

Tunnel Dimensions

The passages measure approximately 2.6 meters wide and 1.6 meters high, though some reports cite slightly different measurements of 8.5 feet wide by 5.2 feet tall. These dimensions were large enough for people to walk through comfortably, or even for the Inca nobility to be carried.

Construction Method

Inca engineers employed the cut-and-cover technique, first excavating trenches along planned routes, then reinforcing them with precisely fitted stone walls. Workers installed carved wooden beams as ceiling supports before covering the entire structure with earth, making the tunnels completely invisible from ground level.

McKay Savage from London, UK, Wikimedia Commons

McKay Savage from London, UK, Wikimedia Commons

Stone Architecture

The tunnel walls exhibit trapezoidal cross-sections built with meticulously carved diorite and andesite blocks, fitted together so tightly that no mortar was needed. This distinctive shape—wider at the base than the top—is unmistakably Inca, providing superior stability during earthquakes by distributing forces efficiently.

Kevin M. Gill, Wikimedia Commons

Kevin M. Gill, Wikimedia Commons

Underground Streets

Researchers believe the tunnel network precisely mirrors Cusco's surface street layout, creating a subterranean duplicate of the city above. This parallel infrastructure suggests the Incas conceived urban space as multi-layered, integrating physical and symbolic dimensions into their capital's design.

Ceremonial Theory

Scholars propose that the tunnels enabled secret movement between Cusco's most sacred sites, allowing priests and nobility to traverse spiritual pathways hidden from public view. The connection between Coricancha and Sacsayhuaman suggests that ceremonial processions may have taken place underground during important festivals like Inti Raymi.

Cyntia Motta, Wikimedia Commons

Cyntia Motta, Wikimedia Commons

Communication Routes

Beyond religious functions, the tunnel system likely served practical administrative purposes, enabling rapid, protected communication across Cusco during emergencies or warfare. The passages could have transported valuable goods, military supplies, or important officials without exposure to potential threats above ground.

Excavation Timeline

Approval processes and preparations led to excavations commencing in late 2025, with the team locating a potential entrance after initial targeted digs. Archaeologists continue focused excavations at key access points rather than wholesale digging, prioritizing structural preservation while seeking artifacts and construction details.

Son of Groucho from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

Son of Groucho from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

Future Mysteries

Countless questions remain unanswered until archaeologists actually enter and explore the passages themselves—no artifacts or biological remains have been recovered yet, and formal dating hasn't begun. The exact construction timeline, maintenance systems, and the tunnels 'complete extent throughout Cusco await investigation.

Caminando Cusco, Wikimedia Commons

Caminando Cusco, Wikimedia Commons