Beyond The Brochure

Most Americans know Old Faithful, but few understand the real Yellowstone story. It's a tale that stretches back thousands of years before park boundaries existed. The landscapes we marvel at today hold intriguing secrets.

Pre-Human Landscape

Three violent supervolcano eruptions shaped Yellowstone over 2.1 million years, creating its unique caldera. The last major eruption occurred 631,000 years ago, ejecting enough ash to blanket much of North America. Subsequent ice ages carved valleys and left glacial debris, while geothermal activity continuously affected the area.

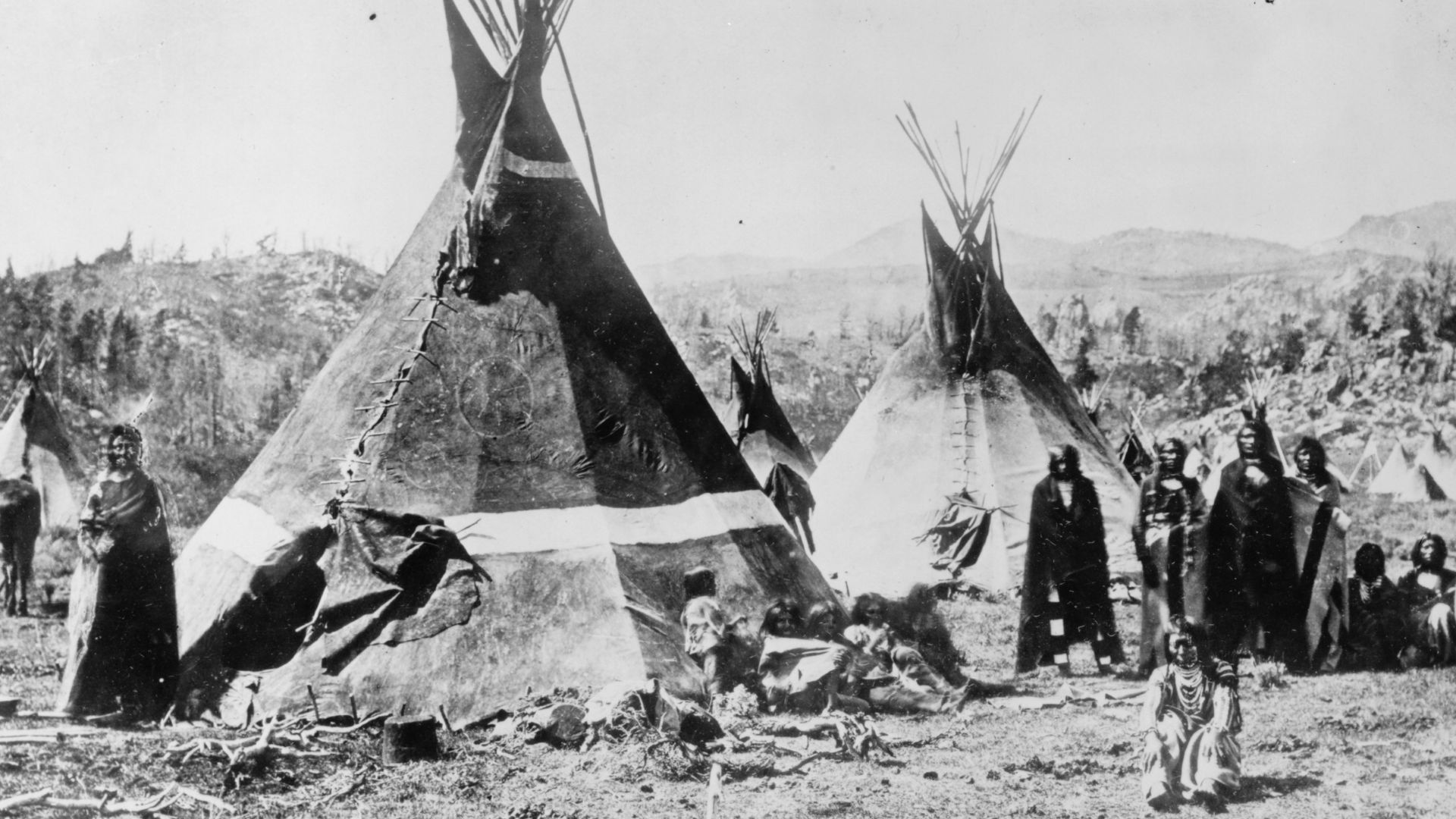

First Inhabitants

Archaeological evidence reveals humans first entered Yellowstone's valleys approximately 11,000 years ago as the last ice age retreated. These Paleo-Indian hunters pursued large game using sophisticated stone tools. What's particularly fascinating is that researchers have uncovered over 1,800 archaeological sites throughout the park.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Indigenous Knowledge

The region's geothermal features held profound spiritual significance for native peoples, who conducted healing ceremonies at hot springs for countless generations. Many tribes considered Yellowstone a neutral zone where traditional enemies could gather peacefully. Their extensive ecological knowledge included medicinal uses for plant species found in the region.

Jon Sullivan, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Sullivan, Wikimedia Commons

Trade Networks

From Obsidian Cliff, a precious volcanic glass traveled through complex trading networks as far east as Ohio, over 2,000 miles away. Chemical analysis allows archaeologists to trace Yellowstone obsidian to specific sites across North America.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

Tribal Territories

At least 27 distinct tribes used Yellowstone's resources, including the Shoshone, Bannock, Blackfeet, Crow, and Nez Perce. One specific group, the Tukudika or "Sheep Eaters," adapted to live year-round in Yellowstone's harsh high country. They developed specialized techniques for hunting bighorn sheep.

W. H. Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

W. H. Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

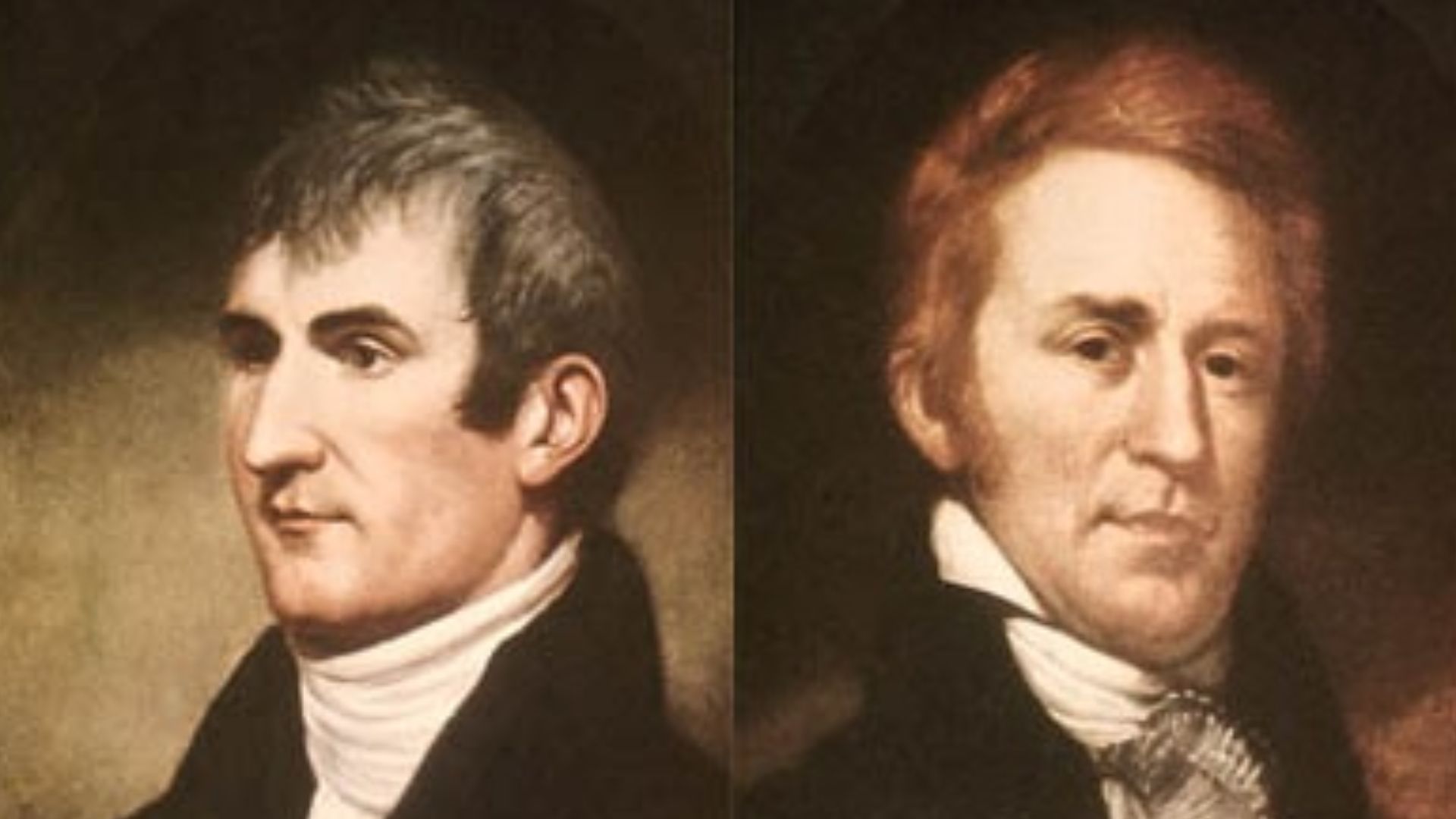

European Contact

Europeans first heard rumors of Yellowstone's wonders through fur trappers returning from the Rocky Mountains in the early 1800s. The Lewis and Clark expedition (1804–1806) traveled north of the region but documented tales of strange smoking lands. Few Americans believed these incredible reports of boiling mud and exploding water.

Colter's Discovery

What would you do after walking 4,000 miles with Lewis and Clark? For John Colter, the answer was exploring Yellowstone alone in winter 1807–1808. Trekking through deep snow in brutal conditions, he became the first documented non-native to witness Yellowstone's geothermal features.

Charles Marion Russell, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Marion Russell, Wikimedia Commons

Frontier Stories

The legendary mountain man Jim Bridger spent decades in Yellowstone beginning in the 1830s. Bridger's colorful accounts described "petrified birds singing petrified songs" and “waterfalls flowing upward”. His reputation for embellishment caused his legitimate observations to be dismissed as fantasy.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

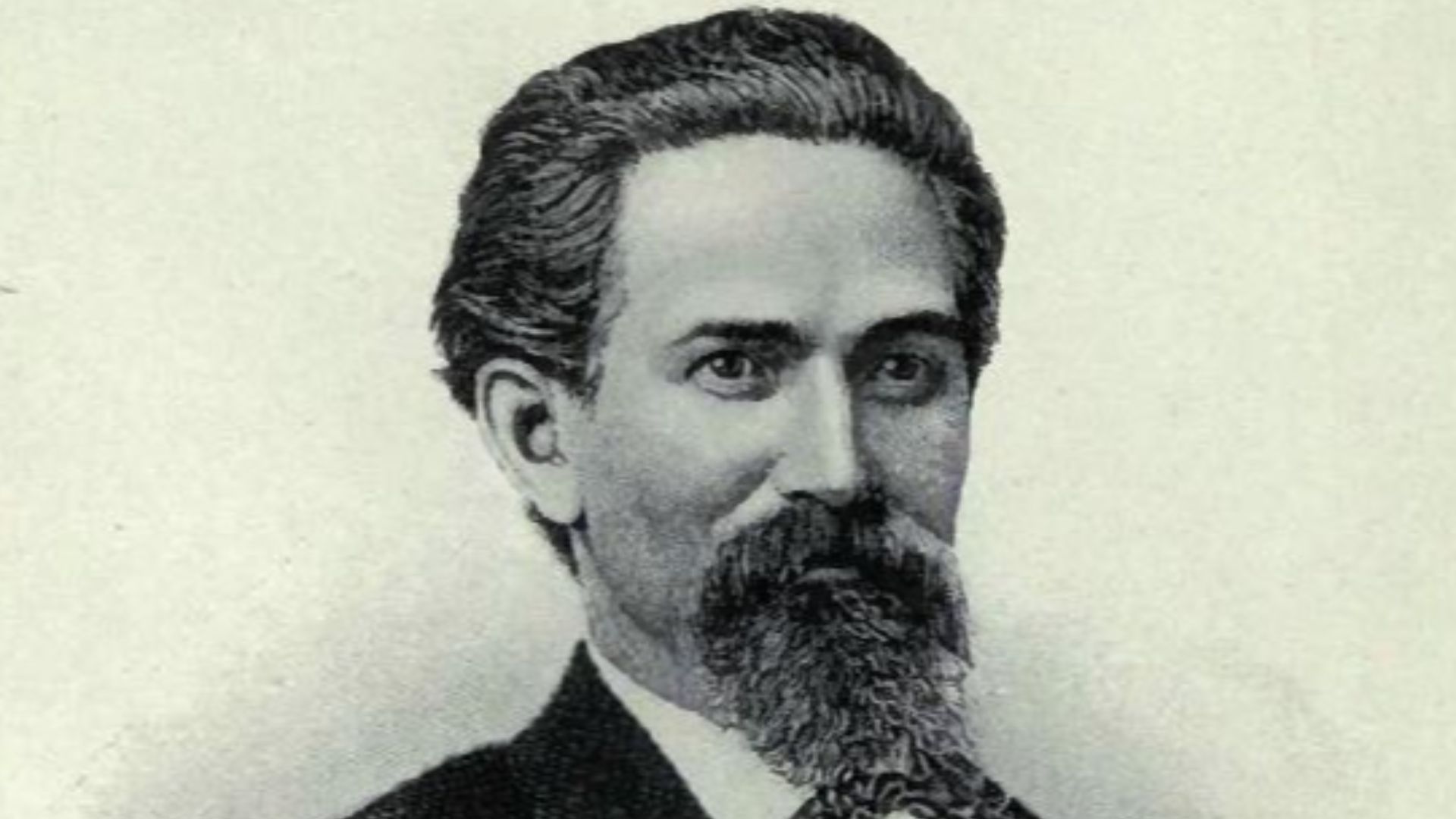

Early Expeditions

Despite gold rushes bringing thousands to Montana by the 1860s, Yellowstone remained virtually unexplored until 1869. That year, three Montana miners—Cook, Folsom, and Peterson—conducted the first organized expedition through the region. Their detailed journals documenting geysers and hot springs were rejected by mainstream publishers as implausible fiction.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Washburn Exploration

In 1870, Surveyor General Henry Washburn led an expedition with Nathaniel Langford and Lieutenant Gustavus Doane. They named Old Faithful for its regular eruptions and explored previously undocumented thermal features. During a campfire discussion near the Madison River, several members allegedly proposed preserving the region as a public park.

Everts Survival

During the Washburn expedition, 54-year-old Truman Everts became separated from the group without supplies or weapons. Lost for 37 days as winter approached, he survived by eating a single thistle plant variety, drinking from hot springs, and sleeping beside thermal vents for warmth.

Scientific Survey

Ferdinand Hayden's 1871 survey represented an important scientific milestone that forever changed American conservation. Unlike previous expeditions, Hayden's 34-member team included specialists in geology, botany, zoology, and topography. The group meticulously documented Yellowstone's features while camping at what's now called "Earthquake Camp" near Yellowstone Lake.

William Henry Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

William Henry Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

Artistic Documentation

What convinced Congress to protect Yellowstone? Visual evidence proved decisive. Thomas Moran's stunning watercolors and oil paintings captured the area’s surreal beauty in vivid color, while William Henry Jackson transported heavy glass photographic plates through rugged terrain to document geysers and canyons.

Thomas Moran, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Moran, Wikimedia Commons

Congressional Debate

The bill to establish Yellowstone faced significant opposition from development interests. Some legislators couldn't comprehend setting aside such vast resources simply for preservation. Wyoming's territorial status actually helped the park's creation, with no state government advocating for local control or development rights.

Erik Whalen, Wikimedia Commons

Erik Whalen, Wikimedia Commons

Grant's Decision

Did you know President Ulysses S Grant never actually visited Yellowstone? On March 1, 1872, he signed legislation creating America's first national park despite having no personal experience with the region. Grant's motivations included genuine conservation values alongside political calculations.

Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Boundary Creation

Yellowstone's boundaries were drawn primarily along straight lines rather than natural features, creating a roughly rectangular park of 3,437 square miles. The boundaries protected most thermal features but arbitrarily cut across ecosystems and wildlife migration routes. Approximately 96% lies within Wyoming, with small portions extending into Montana and Idaho.

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

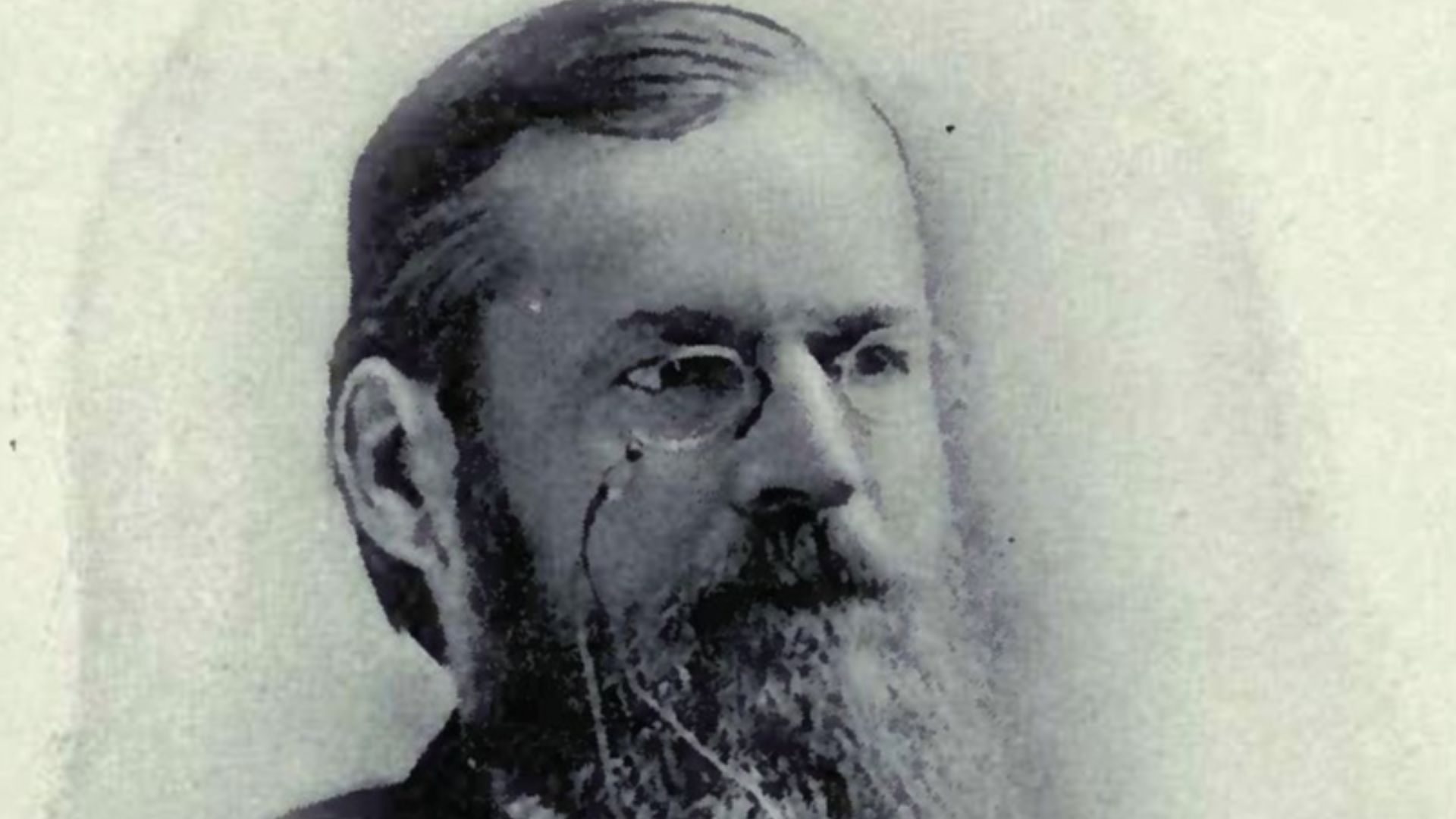

Native Displacement

The myth of an "uninhabited wilderness" justified the forced removal of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands within Yellowstone. Park Superintendent Philetus Norris actively worked to eliminate native presence, spreading false rumors that tribes feared the geothermal features.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Military Management

Facing rampant poaching and vandalism, in 1886, the US Army assumed control of Yellowstone for the next 30 years. Cavalry troops established Camp Sheridan (later Fort Yellowstone) at Mammoth Hot Springs. Military engineers constructed roads, bridges, and buildings still used today.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

First Infrastructure

Early visitors to Yellowstone endured challenging conditions that modern tourists would find unimaginable. The first stagecoach entered in 1878, while the Northern Pacific Railroad reached the north entrance in 1883, bringing wealthy tourists in increasing numbers. Initial accommodations were primitive tent camps.

F. Jay (Frank Jay) Haynes, Wikimedia Commons

F. Jay (Frank Jay) Haynes, Wikimedia Commons

Tourism Beginnings

The first full year of operation (1873) saw only 500 brave visitors enter Yellowstone. Early tourists required significant wealth and fortitude—typical tours lasted 5 days and cost approximately $40 (equivalent to over $1,000 today). A milestone moment arrived in 1883.

National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection, Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection, Wikimedia Commons

Conservation Pioneers

Harry Yount, hired as Yellowstone's gamekeeper in 1880, is considered America's first national park ranger. Working alone in the vast wilderness, he quickly realized one person couldn't protect such an immense area. His recommendation for "a small and reliable police force" laid the groundwork for the ranger service.

William Henry Holmes (1846–1933)[2], Wikimedia Commons

William Henry Holmes (1846–1933)[2], Wikimedia Commons

Ecological Research

Yellowstone functioned as America's first natural laboratory, where scientists could study undisturbed ecosystems. The controversial wolf reintroduction in 1995 triggered what ecologists call a "trophic cascade"; wolves reduced elk populations, allowing willows and aspens to recover, which then supported beaver colonies.

William Henry Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

William Henry Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

Development Challenges

The tension between preservation and tourism has defined Yellowstone's history. Should visitors experience wilderness on its own terms or with modern comforts? Early road construction was deliberately planned to showcase dramatic views while concealing human infrastructure. The 1988 fires burned 36% of the park, shocking the public.

Preservation Battles

In 1978, UNESCO designated Yellowstone a World Heritage Site, recognizing its global significance. Surprisingly, from 1995 to 2003, it was placed on the "In Danger" list due to mining threats, invasive species, and tourism pressures. Just outside park boundaries, conservationists have fought numerous proposals that would harm Yellowstone's ecosystem.

Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons

Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons