The Red Stone Legacy

Every culture leaves marks, some in writing, others in stone. Here, the red quarries in southwestern Minnesota, USA whispered their own tale, one guarded fiercely through struggle and time.

The Ancient Plains Where Pipestone Quarry Took Shape

Glacial ice once covered the prairie, grinding down layers of Sioux quartzite. When the ice retreated, valleys formed across today’s Minnesota. In one exposed seam lay red argillite, later called catlinite, a geological deposit that dates back over one billion years.

The Rare Red Stone Found Only At Pipestone

Catlinite occurs only in a small geological band within Pipestone County. It sits beneath hard quartzite layers, and to remove it, you need to be careful. When freshly quarried, it measures about 2 on the Mohs hardness scale, soft enough to carve intricate detail before curing.

Twyla Baker, Wikimedia Commons

Twyla Baker, Wikimedia Commons

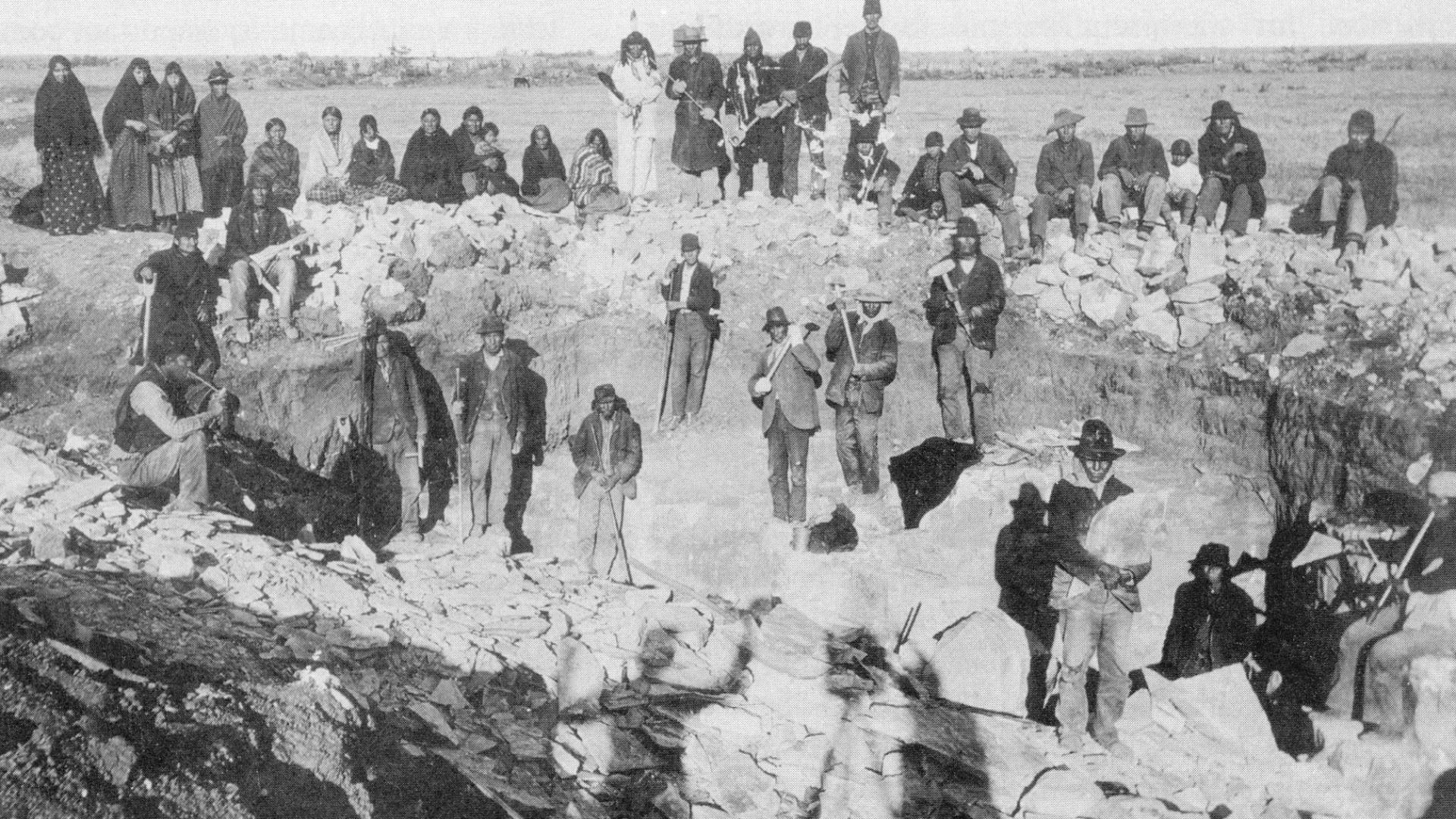

Tribes That First Quarried The Sacred Stone

Archaeological surveys show quarrying activity here for at least 3,000 years. Tools found include hammerstones and antler picks. The Dakota, Lakota, and Ojibwe each maintained quarrying traditions, with pits passed down through generations within their respective families.

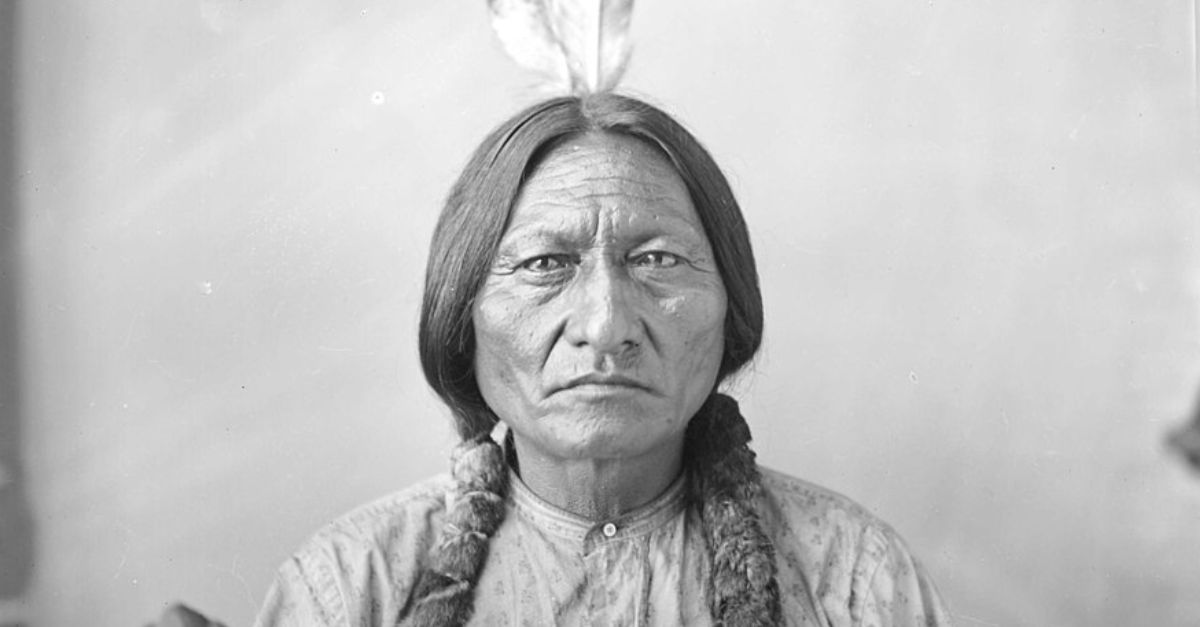

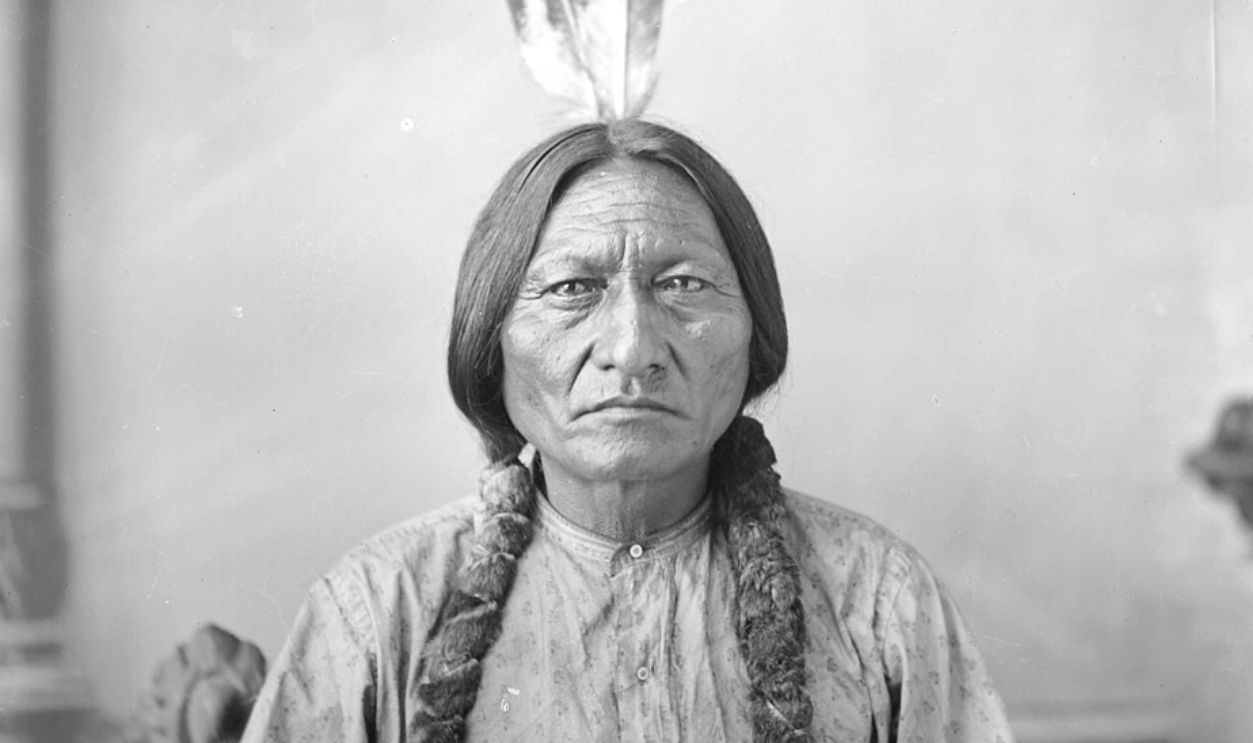

Earl Alonzo Brininstool, Wikimedia Commons

Earl Alonzo Brininstool, Wikimedia Commons

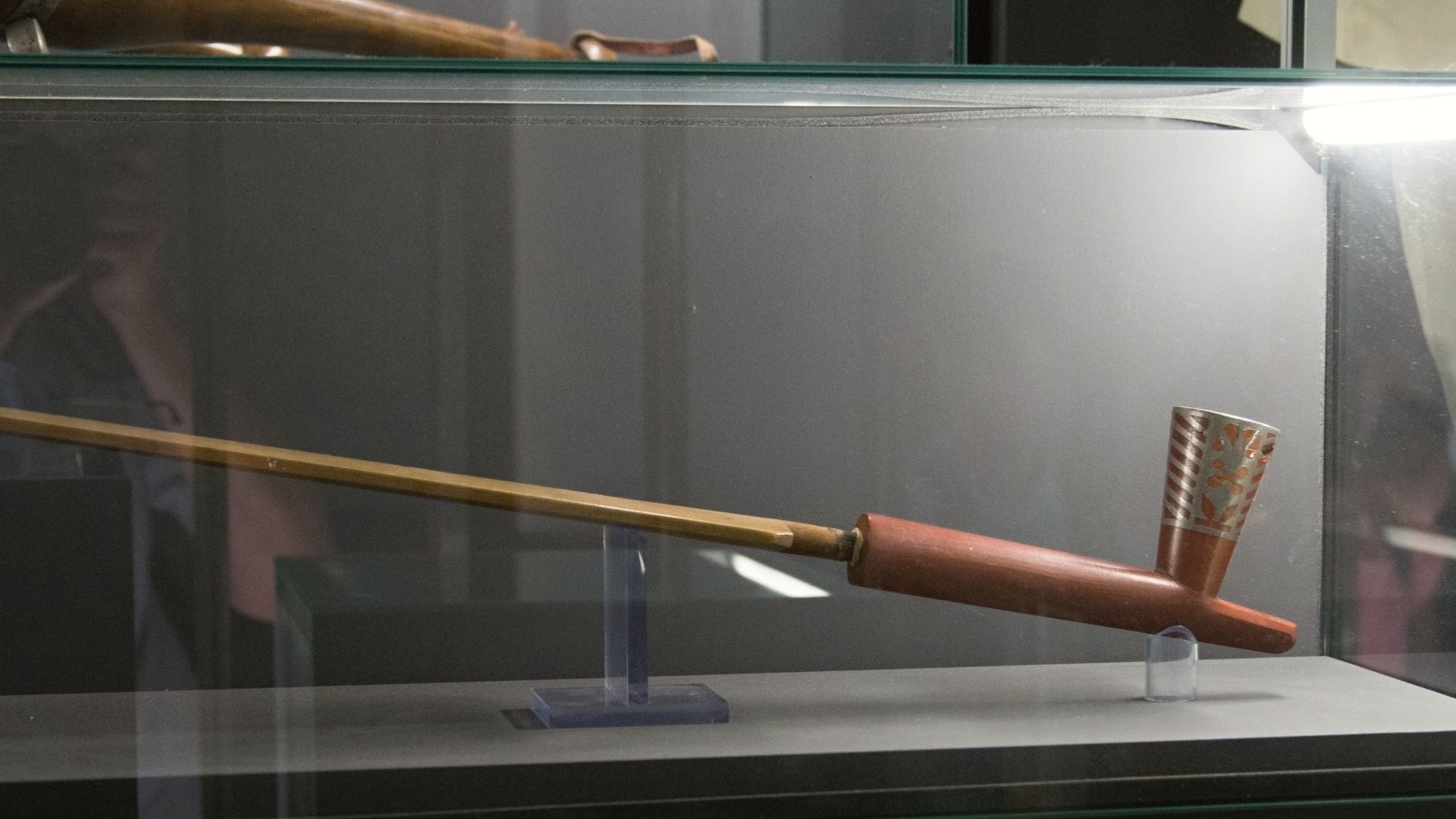

Ceremonial Pipes That Traveled Thousands Of Miles

Pipestone pipes have been excavated from burial mounds across North America. Artifacts appear in sites in the Midwest and Great Plains, including Ohio and Illinois. Their wide distribution proves the quarry’s central role in pre-Columbian trade networks.

Museum staff, Wikimedia Commons

Museum staff, Wikimedia Commons

How Generations Passed Quarrying Traditions By Hand

The removal process began with stripping quartzite layers before extracting catlinite. Metal wedges, struck with hammers, were used to split stone seams. Hand tools were used to shape blocks into portable sizes. Generational continuity is confirmed through stratified pit layers, which are studied by archaeologists.

The Yankton Dakota And Their Sacred Rights At Pipestone

The Yankton Dakota negotiated the 1858 treaty specifically to secure rights to quarry. Article VIII guaranteed them “free and unrestricted use” of the quarry lands. One square mile was designated as reservation territory surrounding the quarry to create a legally recognized boundary.

Spiritual Beliefs That Made The Quarry Untouchable

Dakota oral tradition ties the stone to ancestral sacrifice. The red coloration symbolized blood, binding human life to the quarry. Pipes carved from catlinite became instruments for prayer. These beliefs made quarrying a spiritual obligation rather than a simple craft.

Early European Encounters With Pipestone Quarry

French fur traders recorded stories of a red stone quarry by the 1600s. By the 1700s, explorers marked it on regional maps. Written accounts describe both the stone’s physical properties and Native restrictions placed on quarry access for outsiders.

Joseph Drayton (1795-1856), member of Charles Wilkes's expedition., Wikimedia Commons

Joseph Drayton (1795-1856), member of Charles Wilkes's expedition., Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin’s 1830s Paintings Of The Quarry

In 1836, George Catlin visited Pipestone and created detailed paintings of its cliffs and workers. His writings accompanied the artworks, describing quarry rituals and stone carving. The mineral later received the name “catlinite” in recognition of his documentation.

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

George Catlin, Wikimedia Commons

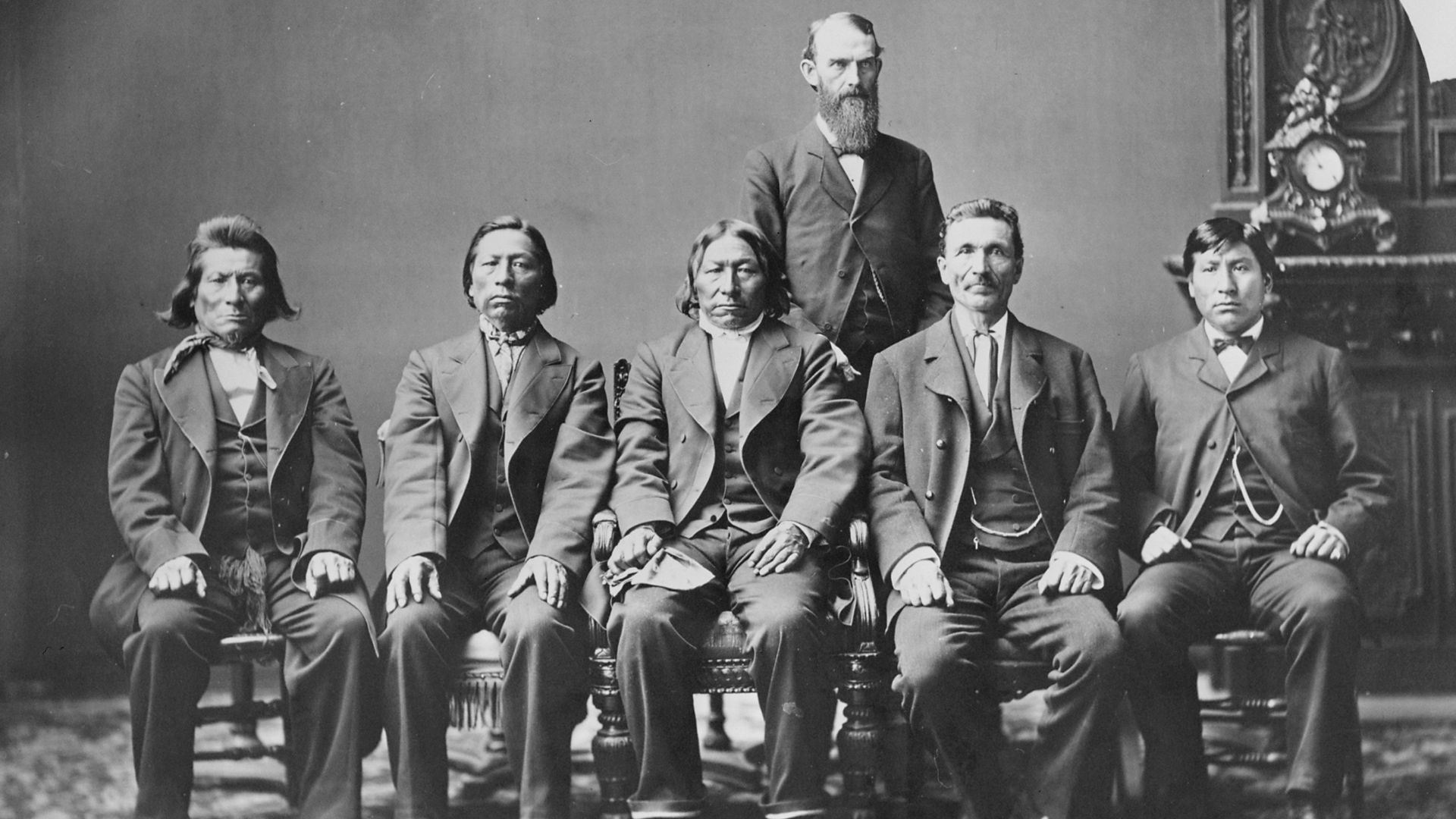

The US Treaty Of 1858 Promising Quarry Access Forever

About 22 years later, in 1858, the Yankton Dakota signed a treaty in Washington, DC, ceding over eleven million acres of land. Within that agreement, one square mile at Pipestone Quarry was specifically reserved. This provision formally acknowledged the quarry’s sacred value while establishing legal protection for Native access.

Photographer from New York, Wikimedia Commons

Photographer from New York, Wikimedia Commons

Article VIII: The Legal Language That Shaped The Future

Article VIII of the 1858 treaty granted Yankton Dakota “free and unrestricted use” of Pipestone Quarry. Its wording became central to later disputes, as courts debated whether the article guaranteed perpetual ownership or merely the right to quarry. That phrasing influenced legal battles lasting well into the twentieth century.

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

Settler Encroachment Begins Around The Quarry Lands

By the 1860s, Euro-American settlers moved into Pipestone County. Homesteaders staked claims adjacent to the quarry despite federal designations. Town development increased demand for surrounding farmland. Encroachment quickly undermined the intent of the 1858 treaty’s protected boundary.

Homestead Patents Granted Illegally On Quarry Grounds

Records show federal agents issued homestead patents within the reserved quarry lands. These patents, which violated treaty terms, remained on file. Families constructed farms and houses on land originally excluded from settlement under the treaty’s reservation clause.

Pierce, C.C. (Charles C.), 1861-1946, Wikimedia Commons

Pierce, C.C. (Charles C.), 1861-1946, Wikimedia Commons

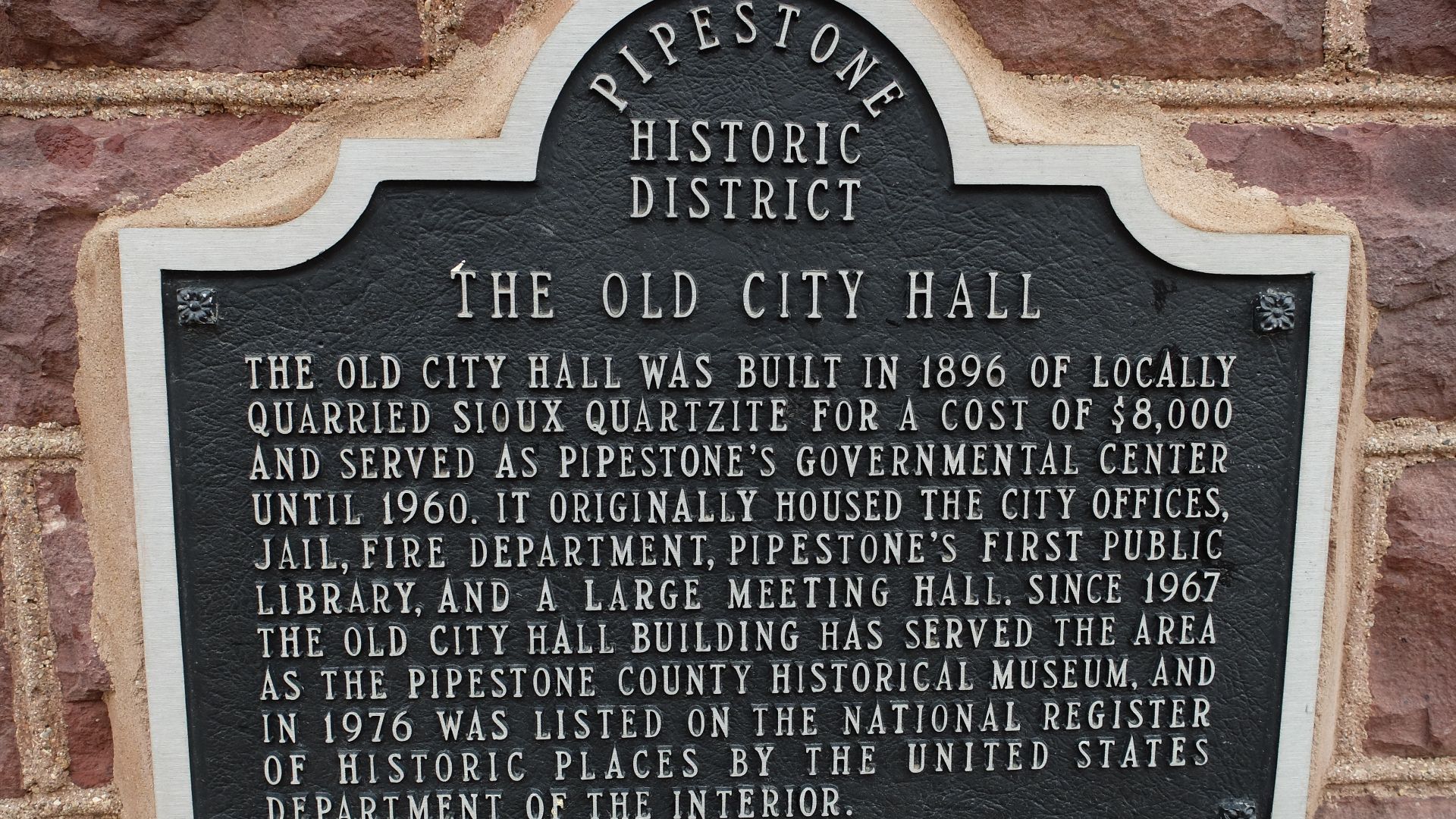

Local Pipestone Officials Ignoring Federal Promises

The newly established town of Pipestone was incorporated in 1883. Local leaders, including the mayor, authorized construction inside the reservation zone. Municipal boundaries overlapped with quarry lands, disregarding federal obligations. Town expansion directly conflicted with the Yankton Dakota treaty protections.

The Building Of The Pipestone Indian School On Sacred Land

Come 1892, the federal government opened the Pipestone Indian School. The campus sat within the quarry reservation’s borders. Native children from across the Plains attended under assimilation policies. School buildings consumed large portions of the land reserved for quarrying.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Government Ambiguity Over “Use” Versus “Ownership”

Federal authorities interpreted Article VIII as a right of access, not ownership. This narrowed reading allowed land allocations for non-Native use. Court cases later reinforced this distinction, leaving quarrying rights intact but stripping broader control from the Yankton Dakota.

Legal Battles Over Treaty Rights In The Late 1800s

Disputes arose between the Yankton Dakota and settlers over access to quarries. Lawsuits questioned whether the treaty guaranteed permanent land possession. Courts consistently upheld quarrying rights but refused to restore the surrounding land to tribal jurisdiction. This legal stance persisted into the 20th century.

Native Quarrying Continues Despite Rising Hostility

Despite legal and physical obstacles, Native families maintained quarrying. Pits remained active throughout the 19th century. Blocks of catlinite were extracted using traditional methods. Continuity of work is evident in pit records and stone artifacts dated across successive decades.

Settlers’ Failed Attempts To Fully Seize The Quarry

Settlers sought exclusive rights to extract catlinite during the late 19th century. Applications for mining patents were submitted but denied. Federal officials recognized the treaty obligation, preventing settlers from legally monopolizing the quarry despite surrounding land disputes.

How Oral Tradition Preserved The Quarry’s History

Stories describe the quarry as a place where life and sacrifice are intertwined. These narratives survived generations despite displacement. Recorded oral histories in the late 1800s captured versions of these accounts, ensuring cultural continuity even as federal policies disrupted Native communities.

Congressional Action Creating Pipestone National Monument In 1937

In 1937, Congress designated the quarry area as Pipestone National Monument. The law reaffirmed Native quarrying rights while placing the site under federal protection. The National Park Service assumed jurisdiction to strike a balance between preservation mandates and treaty obligations to Native communities.

Quarry Permits Restricted To Native Americans Only

Current law limits quarrying permits to members of federally recognized tribes. The system ensures stone is quarried by hand using traditional methods. Dozens of active permits are issued annually, with waiting lists maintained to regulate access to the limited pits.

Unknown photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Tribes Still Quarry The Stone By Hand

Today’s Native quarriers continue using wedges, hammers, and chisels. Machinery remains prohibited to preserve traditional practice. The process requires clearing quartzite layers before reaching catlinite seams. Annual yields are modest, and this reflects both the stone’s rarity and the effort required.

Today’s Monument Balances Tourism With Sacred Tradition

The National Monument hosts nearly 70,000 visitors each year. Interpretive trails, exhibits, and demonstrations highlight quarrying methods. Native quarriers actively work within view of tourists to provide both cultural education and direct continuity of practice within a protected environment.

English: NPS Photo, Wikimedia Commons

English: NPS Photo, Wikimedia Commons

Pipestone Quarry As A Living Symbol Of Survival And Faith

The quarry remains both a working site and a cultural landmark. Catlinite pipes continue to be used in Native American ceremonies today. Federal protections coexist with enduring tribal traditions, making Pipestone a rare example of treaty rights still honored in practice.

National Park Service Digital Image Archives, Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service Digital Image Archives, Wikimedia Commons