Faith Meets Scrutiny

Centuries ago, a brilliant scholar sat down to untangle strange marvels that puzzled his world. He wasn’t swayed by faith alone. Instead, he pulled apart legends, showing how reason could silence superstition.

Manuscript Discovery

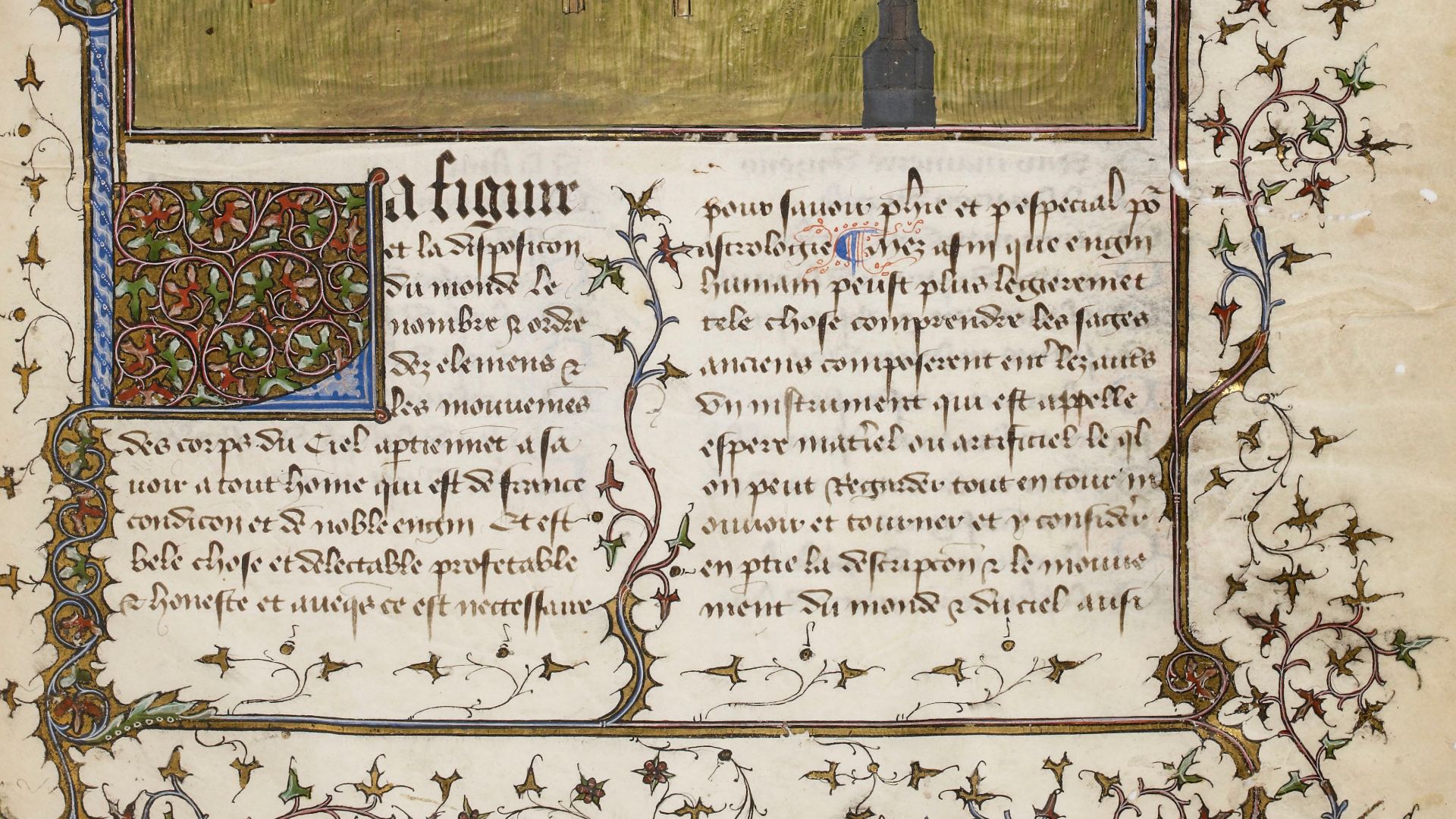

The treatise on "unexplained phenomena," written between 1355 and 1382 by Norman scholar Nicole Oresme, has sent shockwaves through religious and academic circles worldwide. It's a 670-year-old document that tends to demolish one of Christianity's most beloved relics, the Shroud of Turin.

Nicole Oresme / Aristotle, Wikimedia Commons

Nicole Oresme / Aristotle, Wikimedia Commons

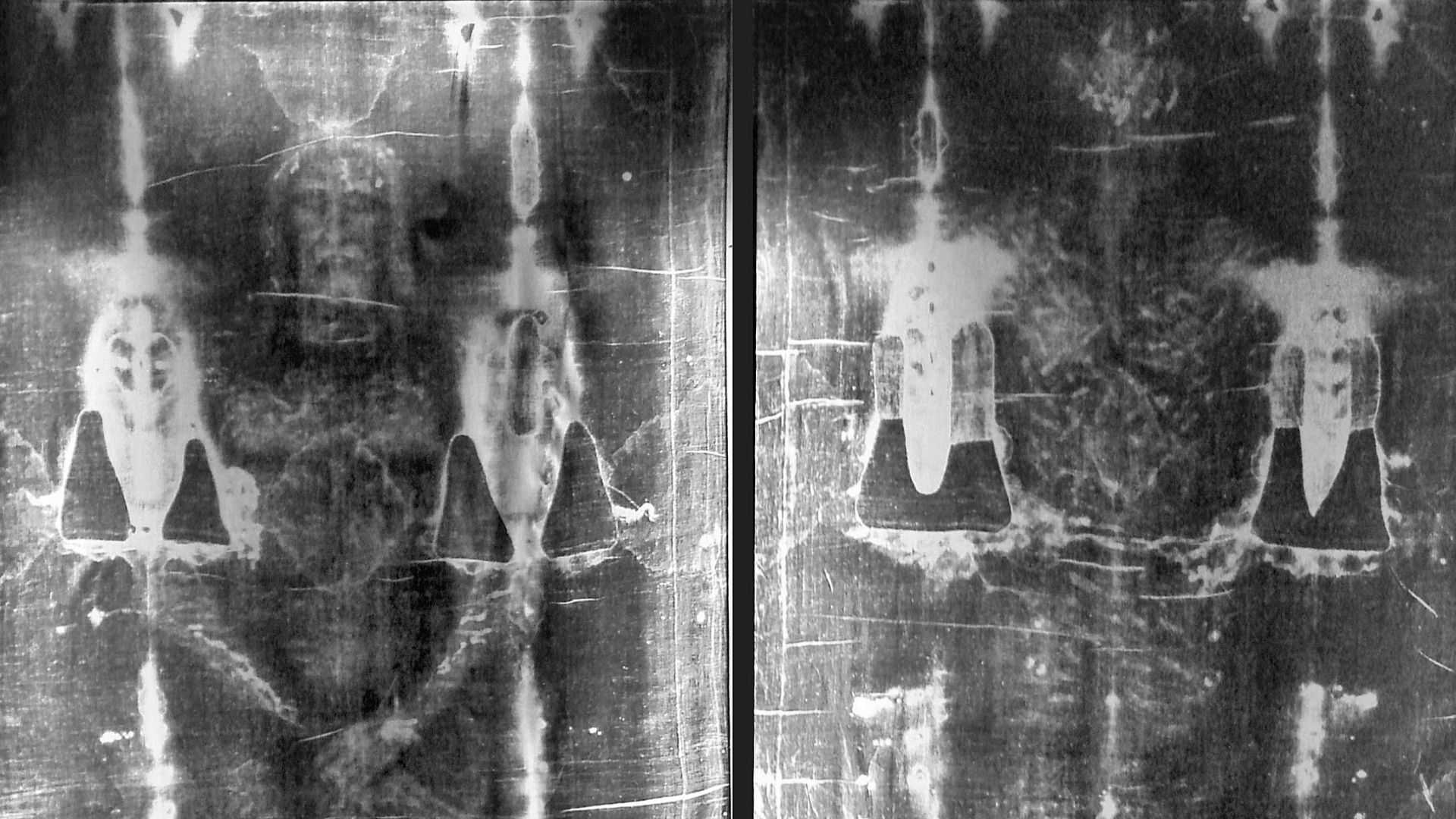

The Shroud Of Turin

This is basically a length of linen cloth bearing the faint image of a man who appears to have suffered physical trauma consistent with crucifixion. Many Christians believe it to be the burial shroud that covered Jesus of Nazareth after his crucifixion.

Giuseppe Enrie, 1931, Wikimedia Commons

Giuseppe Enrie, 1931, Wikimedia Commons

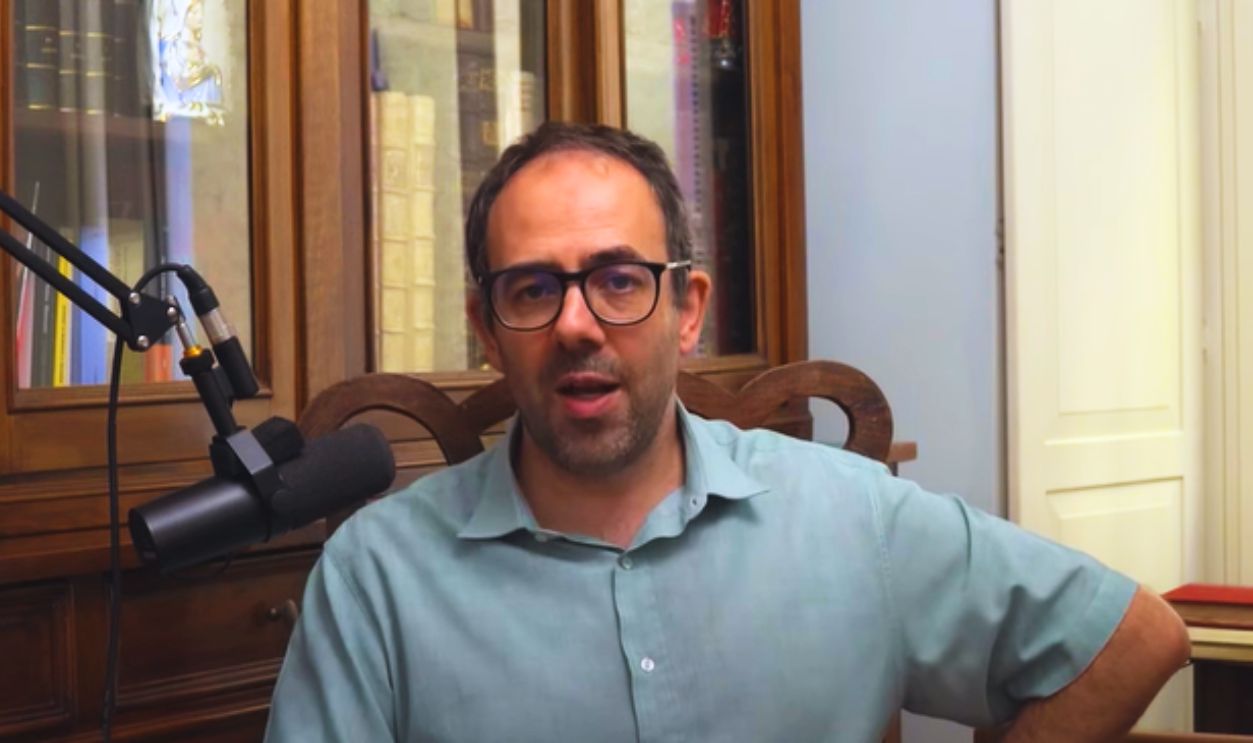

Sarzeaud's Research

Dr Nicolas Sarzeaud, a researcher in history at the Universite Catholique of Louvain, Belgium, and fellow of the Villa Medicis French Academy in Rome, made this discovery. His analysis revealed that a respected 14th-century philosopher had already exposed the Shroud as fraudulent centuries before modern science got involved.

Academic Publication

The academic world rarely gets this excited about medieval manuscripts, but Sarzeaud's paper has created unprecedented buzz. Leading Shroud expert Professor Andrea Nicolotti of the University of Turin called the discovery “particularly important”. The publication represents a watershed moment in Shroud studies.

Le Suaire : entretien avec Andrea Nicolotti, historien by Absinners

Le Suaire : entretien avec Andrea Nicolotti, historien by Absinners

Treatise Dating (1355–1382)

The manuscript dates precisely between 1355 and 1382, with scholars believing Oresme likely wrote about the Shroud around 1370 after learning of the fraud as a scholar to the King of France. This timing is important because it places Oresme's condemnation just fifteen years after the cloth first appeared publicly.

Dianelos Georgoudis, Wikimedia Commons

Dianelos Georgoudis, Wikimedia Commons

Mirabilia Subject

Medieval scholars referred to unexplained phenomena as "mirabilia," meaning "wonderful things" or “marvels”. Oresme's treatise systematically examined various mysterious physical and psychological phenomena reported throughout medieval Europe, applying rational analysis to distinguish genuine mysteries from fraudulent fabrications.

Nicole Oresme / Aristotle, Wikimedia Commons

Nicole Oresme / Aristotle, Wikimedia Commons

Oresme's Identity

Nicole Oresme (1320–1382) was one of medieval Europe's most brilliant minds. He was a French philosopher, mathematician, physicist, economist, and theologian who served as Bishop of Lisieux and translated Aristotelian works for King Charles V of France. His credentials were impeccable.

Gillot Saint-Evre, Wikimedia Commons

Gillot Saint-Evre, Wikimedia Commons

Rational Method

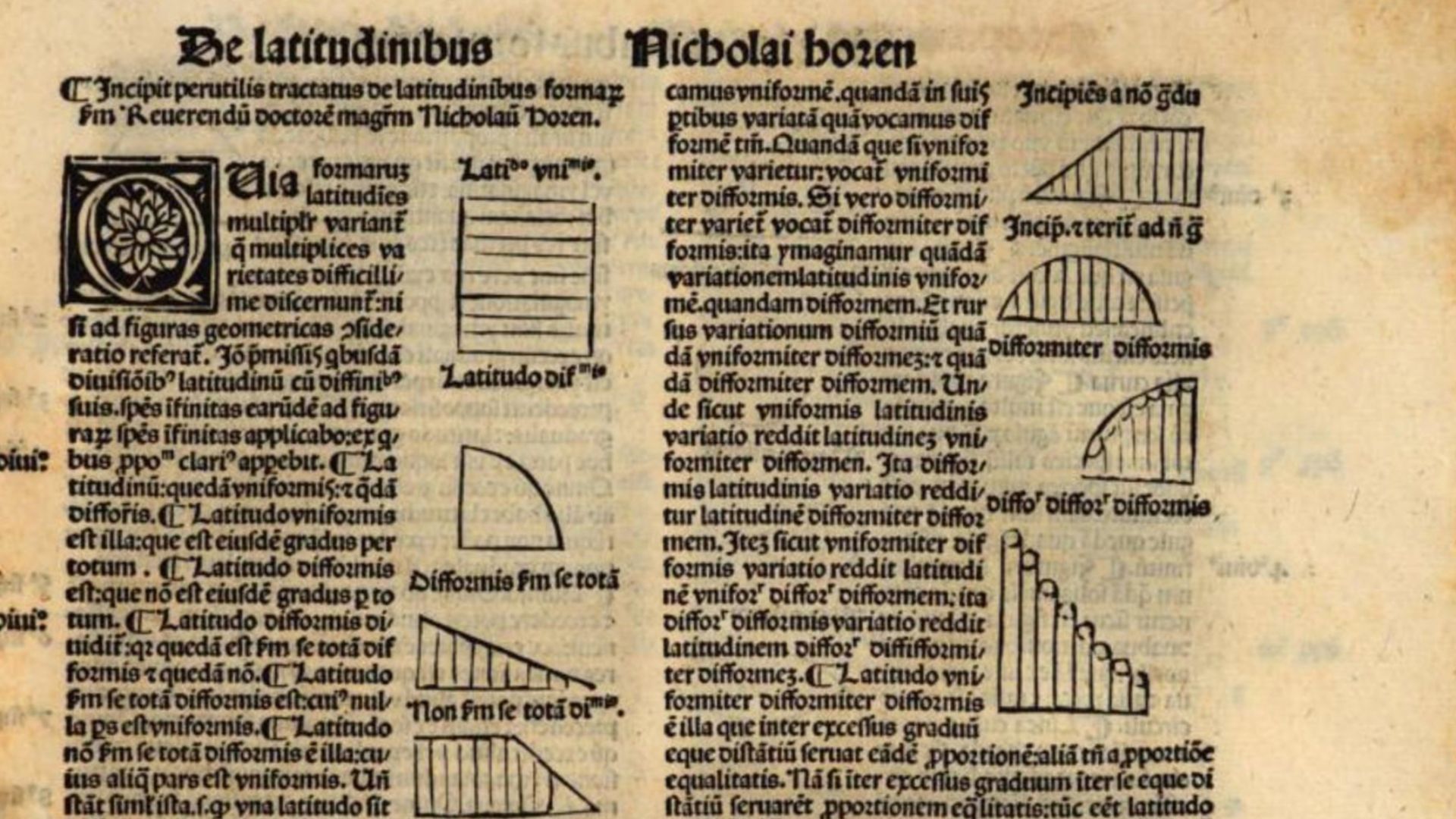

What made Oresme's approach revolutionary was his insistence on providing brilliant explanations for unexplained phenomena, rather than interpreting them as divine or demonic. He also possessed a systematic rating of witnesses according to factors such as their reliability while cautioning against rumors.

Bassano Politi / Nicole Oresme, Wikimedia Commons

Bassano Politi / Nicole Oresme, Wikimedia Commons

Evidence Standards

Oresme developed what we'd now recognize as peer review and fact-checking protocols. He insisted that extraordinary claims required extraordinary evidence, systematically cross-referenced multiple sources, and demanded corroborating testimony from credible witnesses. He argued that simply because "good people" claimed certain events had happened did not make them true.

Natural Explanations

This man took what scholars call a "naturalist's approach" to the unexplained, seeking rational explanations grounded in observable natural processes. He pioneered the principle that natural phenomena have natural causes, even when those causes aren't immediately apparent. This philosophical foundation became essential for later scientific development.

Nicole Oresme (artist unknown), Wikimedia Commons

Nicole Oresme (artist unknown), Wikimedia Commons

Clerical Deception

Oresme's manuscript reveals intriguing insider knowledge about how medieval clergymen systematically deceived faithful believers to extract monetary offerings from their churches. He wrote that "many clergy men thus deceive others, in order to elicit offerings for their churches," exposing a widespread pattern of religious fraud.

Financial Motives

The manuscript exposes the cold, calculating business model behind medieval relic fraud. Churches discovered that displaying supposed holy artifacts attracted pilgrims who paid substantial fees for viewing privileges, purchased blessed items, and made generous donations. Oresme understood that economic incentives drove clerical deception.

Shroud Example

In his treatise, the researcher specifically states: “This is clearly the case for a church in Champagne, where it was said that there was the shroud of the Lord Jesus Christ”. This direct reference to the Shroud's location in the Champagne region identifies the Lirey church without ambiguity.

Arthur Forgeais (1822-1878), Wikimedia Commons

Arthur Forgeais (1822-1878), Wikimedia Commons

Patent Fraud

Oresme didn't mince words when describing the Shroud. He called it a "patent" example of clerical fraud, meaning the deception was so obvious and blatant that it required no sophisticated analysis to detect. The word "patent" in medieval usage meant "open" or “evident”.

Contemporary Knowledge

Sarzeaud's analysis shows that knowledge of the Shroud fraud was "widespread news, reaching as far as Paris," allowing Oresme to cite it confidently. He knew his readers would understand the reference. This indicates that educated medieval society was well aware of the controversy surrounding the cloth.

Anonymous (Category:Artists)Unknown author., Wikimedia Commons

Anonymous (Category:Artists)Unknown author., Wikimedia Commons

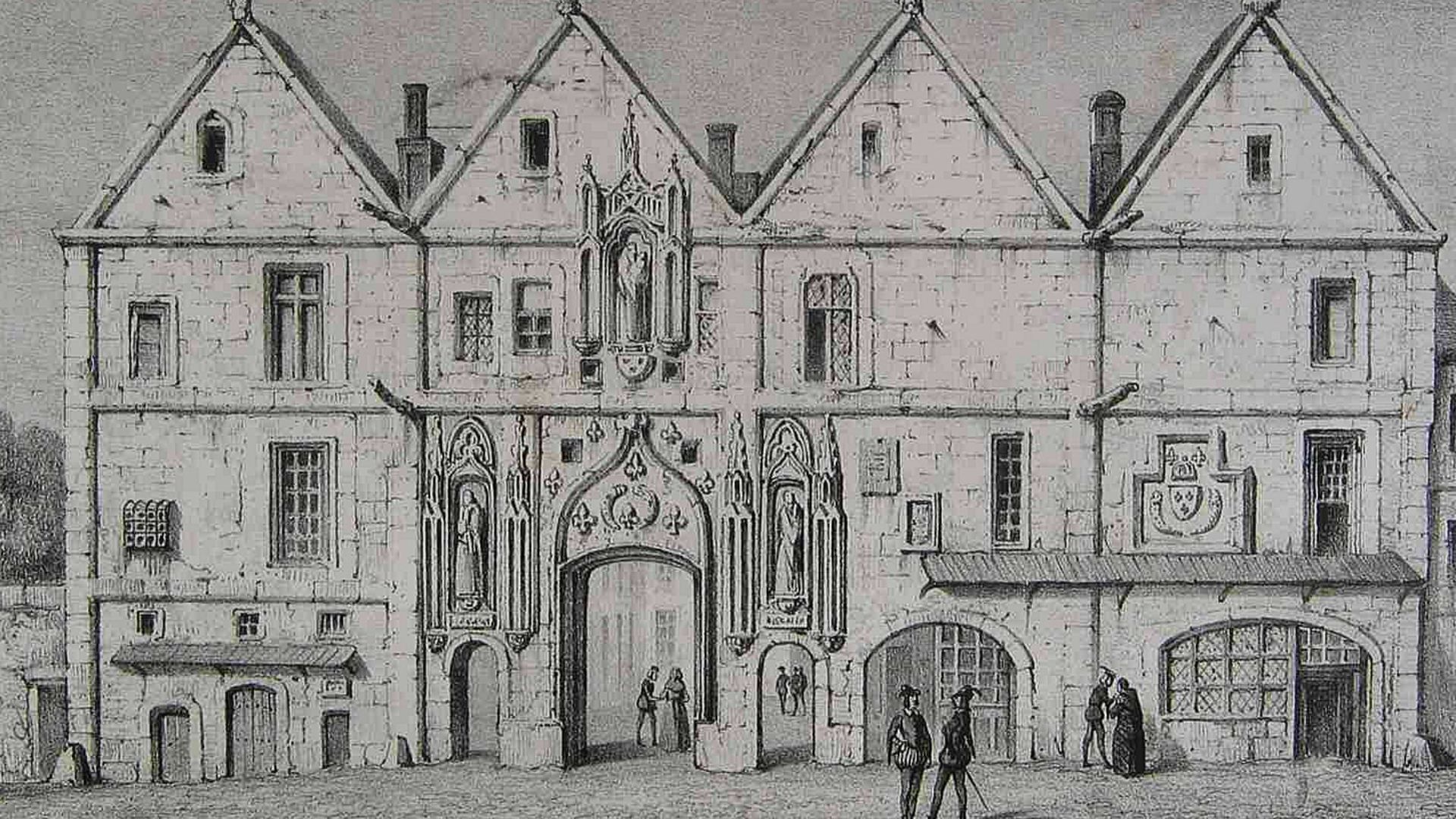

Oresme's Birth

Well, Nicole Oresme emerged from the humblest possible medieval origins, born around 1320–1325 in the tiny village of Allemagne (now Fleury-sur-Orne) near Caen in Normandy's Diocese of Bayeux. His peasant family possessed so little wealth that young Nicole qualified for the royally subsidized College of Navarre in Paris.

Lithographie Nouveaux d'après Pernot, Wikimedia Commons

Lithographie Nouveaux d'après Pernot, Wikimedia Commons

Paris Education

At the University of Paris, Oresme studied under Jean Buridan, the well-known philosopher and logician who founded the French school of natural philosophy and encouraged questioning of Aristotelian doctrines. Buridan's influence proved transformative, teaching Oresme to challenge established authorities.

Nicolas Regnesson (1624–1670), Wikimedia Commons

Nicolas Regnesson (1624–1670), Wikimedia Commons

Academic Rise

By 1342, at roughly age 22, this young man had already achieved regent master status in arts at the University of Paris. His rapid advancement reflected not only extraordinary scholarly ability but also his growing reputation as an original thinker capable of addressing complex theological and philosophical questions.

Étienne Colaud, Wikimedia Commons

Étienne Colaud, Wikimedia Commons

Theology Studies

In 1348, while the Black Death ravaged Europe, Oresme began theological studies at Paris, eventually receiving his doctorate in 1356 before becoming grand master of the prestigious College of Navarre that same year. His theological training provided intimate knowledge of church doctrine, practices, and politics.

Pierart dou Tielt (fl. 1340-1360), Wikimedia Commons

Pierart dou Tielt (fl. 1340-1360), Wikimedia Commons

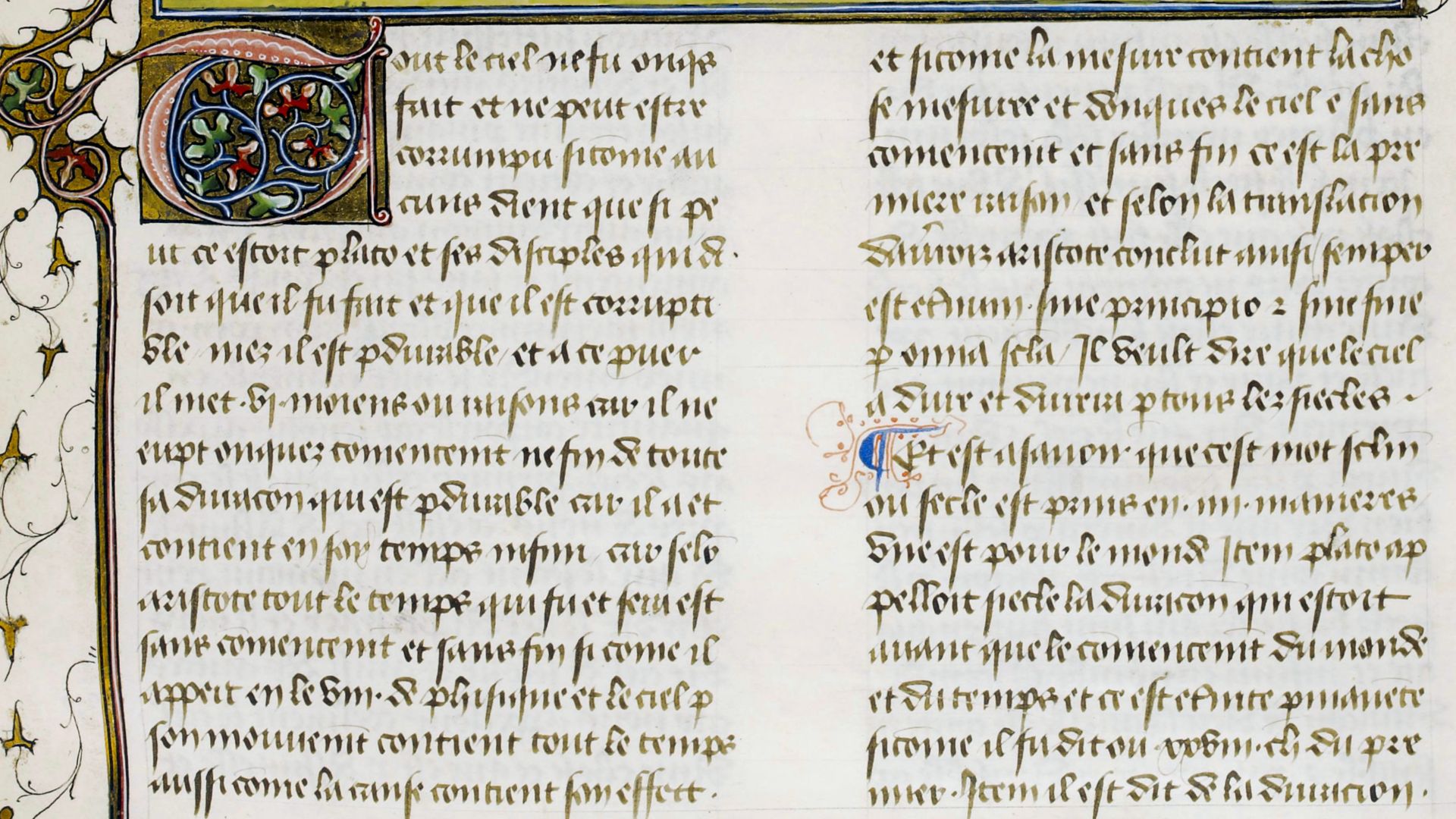

Royal Advisor

King Charles V of France recognized Oresme's exceptional talents and appointed him as royal advisor on various matters, establishing a close friendship that continued throughout their lives. From 1369 onward, at the king's request, Oresme translated numerous Aristotelian works from Latin into French.

AnonymousUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

AnonymousUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Scholarly Works

He authored more than thirty-four books and treatises covering economics, mathematics, physics, musicology, psychology, astronomy, and theology, making him one of history's greatest polymaths. His economic theories anticipated modern concepts by centuries, while his mathematical innovations included coordinate geometry and fractional exponents.

De Moneta

In De Moneta, Oresme argues against the idea that rulers have the unrestricted right to manipulate currency for profit and highlights the social harm of such practices. He anticipates what later became known as Gresham’s Law and stresses that money primarily belongs to the community.

Maxime Cambreling, Wikimedia Commons

Maxime Cambreling, Wikimedia Commons

Bishop Appointment

With royal support, Oresme was appointed Bishop of Lisieux in 1377, reaching the pinnacle of ecclesiastical authority and making his criticism of clerical fraud even more significant. As a bishop, he possessed insider knowledge of church operations, financial practices, and the political pressures that influenced religious decision-making.

The original uploader was Osbern at French Wikipedia., Wikimedia Commons

The original uploader was Osbern at French Wikipedia., Wikimedia Commons

Bishop Of Lisieux

He was formally consecrated as bishop in 1377. Though his bishopric duties centered in Lisieux, Normandy, Oresme kept strong connections to the University of Paris and the French royal court. During this period, he continued to support King Charles V of France as a royal counselor.

Death Legacy

Oresme passed away on July 11, 1382, at Lisieux, leaving behind an intellectual legacy that influenced scientific and philosophical thought for centuries. His rational approach to investigating alleged miracles established important precedents for later scientific methodology, while his economic theories shaped modern understanding of monetary systems.

The Shroud’s First Appearance

Talking about the Shroud, it burst onto the medieval scene around 1354 when it mysteriously appeared in the possession of French knight Geoffroi de Charny at his modest fief of Lirey, near Troyes in north-central France. No historical record explains how Charny acquired this cloth.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Geoffroi's Mystery

Geoffroi de Charny was a famous knight who fought valiantly during the early years of the Hundred Years' War, eventually dying heroically at the Battle of Poitiers while defending King John II of France. Despite his chivalric reputation, Charny maintained absolute secrecy about the Shroud's origins.

Virgil Master (illuminator), Wikimedia Commons

Virgil Master (illuminator), Wikimedia Commons

Lirey Church

In 1353, Charny founded a small collegiate church at Lirey specifically to house religious relics and deliver spiritual services for the local community. Curiously, his detailed Act of Foundation, still preserved in the Troyes archives, makes absolutely no mention of possessing Christ's burial cloth.

ArchivesNationalesBot, Wikimedia Commons

ArchivesNationalesBot, Wikimedia Commons

Early Exhibitions

Public exhibitions of the Shroud began around 1357, shortly after Charny's demise, when his widow, Jeanne de Vergy, and son, Geoffroi II, displayed the piece to attract pilgrims and generate substantial revenue for their church. These displays proved highly lucrative.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Bishop Investigation

Bishop Henri de Poitiers of Troyes launched an official investigation into the Shroud's authenticity, reportedly discovering that the cloth was "cunningly painted" after finding the contemporary artist who had created it. His investigation concluded that the supposed relic constituted deliberate fraud designed to deceive faithful pilgrims.

Church Opposition

Bishop Pierre d'Arcis of Troyes wrote a lengthy memorandum to Pope Clement VII at Avignon in 1389, denouncing the Shroud as a forgery and describing how his predecessor had identified the artist who painted it. D'Arcis reported that the cloth bore "the double imprint of a crucified man”.

Sebastiano del Piombo, Wikimedia Commons

Sebastiano del Piombo, Wikimedia Commons

Papal Response

Rather than supporting his bishop's investigation, Pope Clement VII chose political compromise over truth, issuing bulls in 1390 that allowed continued Shroud exhibitions while carefully avoiding any definitive statement about the cloth's authenticity. The pope ordered Bishop d'Arcis to keep silent about the fraud under threat of excommunication.

Secundo Pia, Wikimedia Commons

Secundo Pia, Wikimedia Commons

Savoy Purchase

In 1453, Marguerite de Charny, Geoffroi's granddaughter, transferred the Shroud to Duke Louis I of Savoy in exchange for valuable territorial grants, including the castle of Varambon. This massive exchange indicated the cloth's perceived value as a diplomatic currency and religious asset.

Marguerite De Charny

Her first husband was Jean de Bauffremont, who died at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 during the Hundred Years' War. After becoming widowed, Marguerite married Humbert de Villersexel, Count of Montrevel, in 1418. During their marriage, there were ongoing conflicts and instability in the region.

Marguerite De Charny (Cont.)

Because of this, Marguerite and Humbert took measures to protect the Shroud of Turin by moving it from its original home in Lirey to safer places, including the castle of Montfort. Humbert de Villersexel died in 1438, leaving Marguerite a widow for the second time.

Duke Louis I

Louis I and his wife, Anne of Lusignan, treated the Shroud with great reverence, viewing it as a dynastic and religious symbol. Soon after acquiring it, Louis I issued a medal in honor of the Shroud, reflecting its importance to the family.

the lost gallery, Wikimedia Commons

the lost gallery, Wikimedia Commons

Turin Transfer

The Savoy family shifted the Shroud to their new capital city of Turin in 1578, where it has remained ever since in the specially constructed Chapel of the Holy Shroud designed by architect Guarino Guarini. This transfer established the relic's permanent association with Turin.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Savoy Family

The Savoy family, also known as the House of Savoy, is a historic European royal dynasty based initially in the Savoy region (now parts of modern France, Italy, and Switzerland). It played an important role in preserving, promoting, and enhancing the Shroud's status through centuries of European history.

Giuseppe Duprà, Wikimedia Commons

Giuseppe Duprà, Wikimedia Commons

Modern Photography

Photographer Secondo Pia produced the first photographic images of the Shroud in 1898, making a startling discovery that changed modern perceptions of the medieval relic. When developed, his photographic negatives showcased much clearer images of the human figure than were visible to the unaided eye.

Scientific Testing

The Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) conducted extensive scientific examination in 1978, employing advanced analytical techniques including microscopy, spectroscopy, photography, and chemical analysis to investigate the cloth's properties and condition. Their comprehensive testing detected no evidence of paint, pigment, or artistic materials on the fabric.

Carbon Dating

Three independent laboratories conducted radiocarbon dating tests in 1988 using samples from the Shroud, with the University of Arizona, Oxford University, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology all reaching identical conclusions. Their analysis determined that the linen dated to between 1260 and 1390 CE.

Baah Thomas, Wikimedia Commons

Baah Thomas, Wikimedia Commons

Statistical Problems

Subsequent statistical research of the 1988 radiocarbon data highlighted significant inconsistencies that challenged the reliability of the medieval dating conclusions. The most recent 2020 analysis found that adjusting results from two laboratories by just ten years would resolve data inconsistencies, while an 88-year adjustment would make all results statistically agree.

National Cancer Institute, Unsplash

National Cancer Institute, Unsplash

Data Controversies

In 2017, following legal pressure, the British Museum released raw data from the 1988 radiocarbon testing, highlighting troubling patterns. Statistical examination showed a systematic spatial gradient in dates along the sampled area, suggesting the tested material might have come from different time periods.

Scientific Validation

Professor Andrea Nicolotti, the world's leading Shroud expert at the University of Turin, emphasized that Oresme's opinion carries special importance "because it comes from a person who was not personally involved in the dispute—and therefore had no interest in supporting his own position”.