When The Ice Melts, The Past Unfreezes

Among 56 artifacts uncovered across nine melting ice patches was a leather-wrapped bundle that surfaced during environmental assessment work in Mount Edziza Provincial Park. The rest? Some dated back 3,000 years, others as far as over 7,000.

A Serendipitous Encounter In The Ice

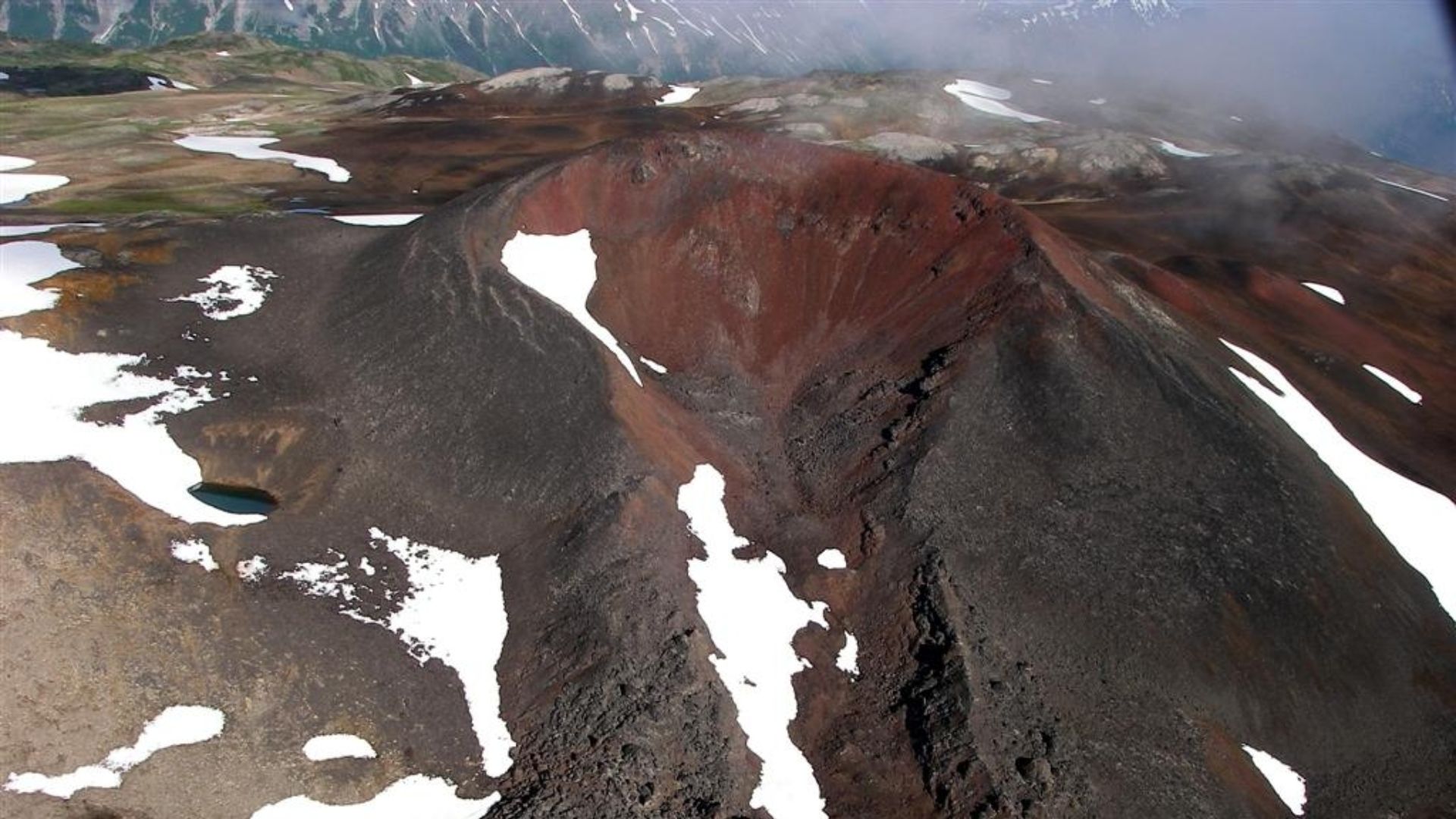

In 2019, a routine environmental assessment in Mount Edziza Provincial Park led to an unexpected archaeological breakthrough. As part of a cultural heritage review commissioned by the Tahltan Nation and the British Columbia government, surveyors documented the effects of climate change on alpine landscapes. Amid melting ice, they spotted something.

A Bundle Preserved By Time And Terrain

The standout artifact was a compact, leather-wrapped bundle that emerged from a high-altitude wetland, nestled within the park’s volcanic terrain. This cold, icy, marshy environment likely acted as a natural vault that preserved the organic materials for thousands of years.

Jagged Ridge Imaging, Wikimedia Commons

Jagged Ridge Imaging, Wikimedia Commons

Radiocarbon Dating Anchors The Timeline

Shortly after recovery, radiocarbon testing placed the bundle’s origin around 1000 BCE. This date situates it within a dynamic period of cultural development among Indigenous communities, the ancestors of the Tahltan. The dating’s precision helped researchers contextualize the artifacts within broader patterns of seasonal migration and spiritual practice.

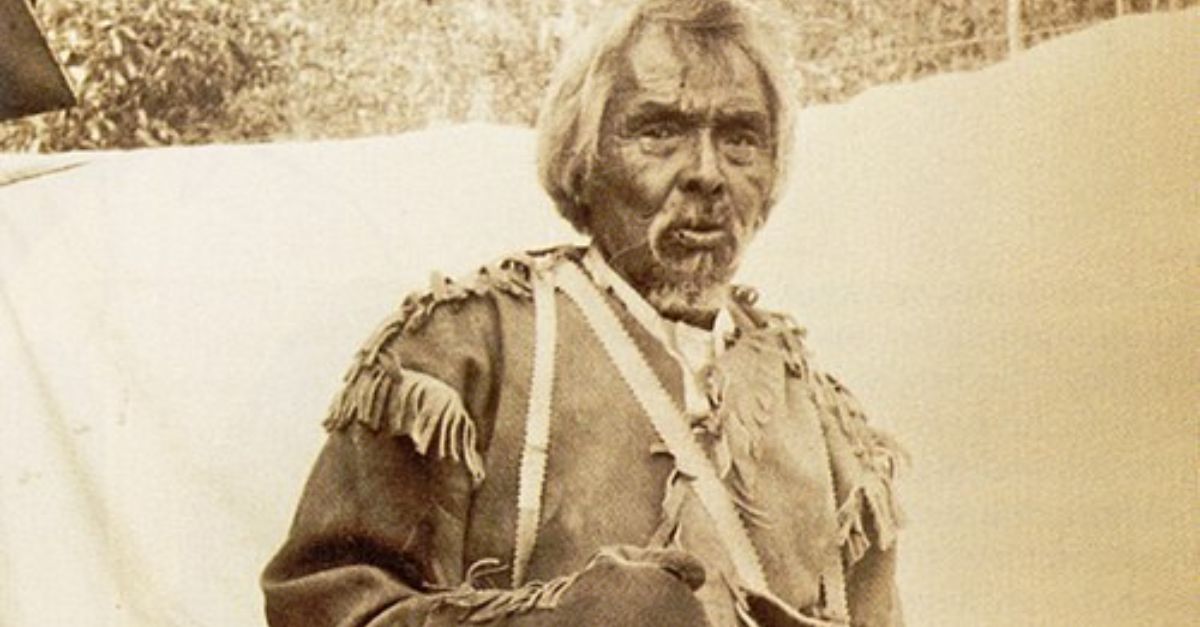

Andrew Jackson Stone (1859–1918), Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Jackson Stone (1859–1918), Wikimedia Commons

But Who Are The Tahltan People?

The Tahltan are a Dene-speaking Indigenous people whose ancestral territory spans northwestern British Columbia, centered around the Stikine River and the volcanic landscapes of Mount Edziza. For over 10,000 years (with obsidian use from that era and perishable artifacts from ~7,000 years onward), they lived in harmony here.

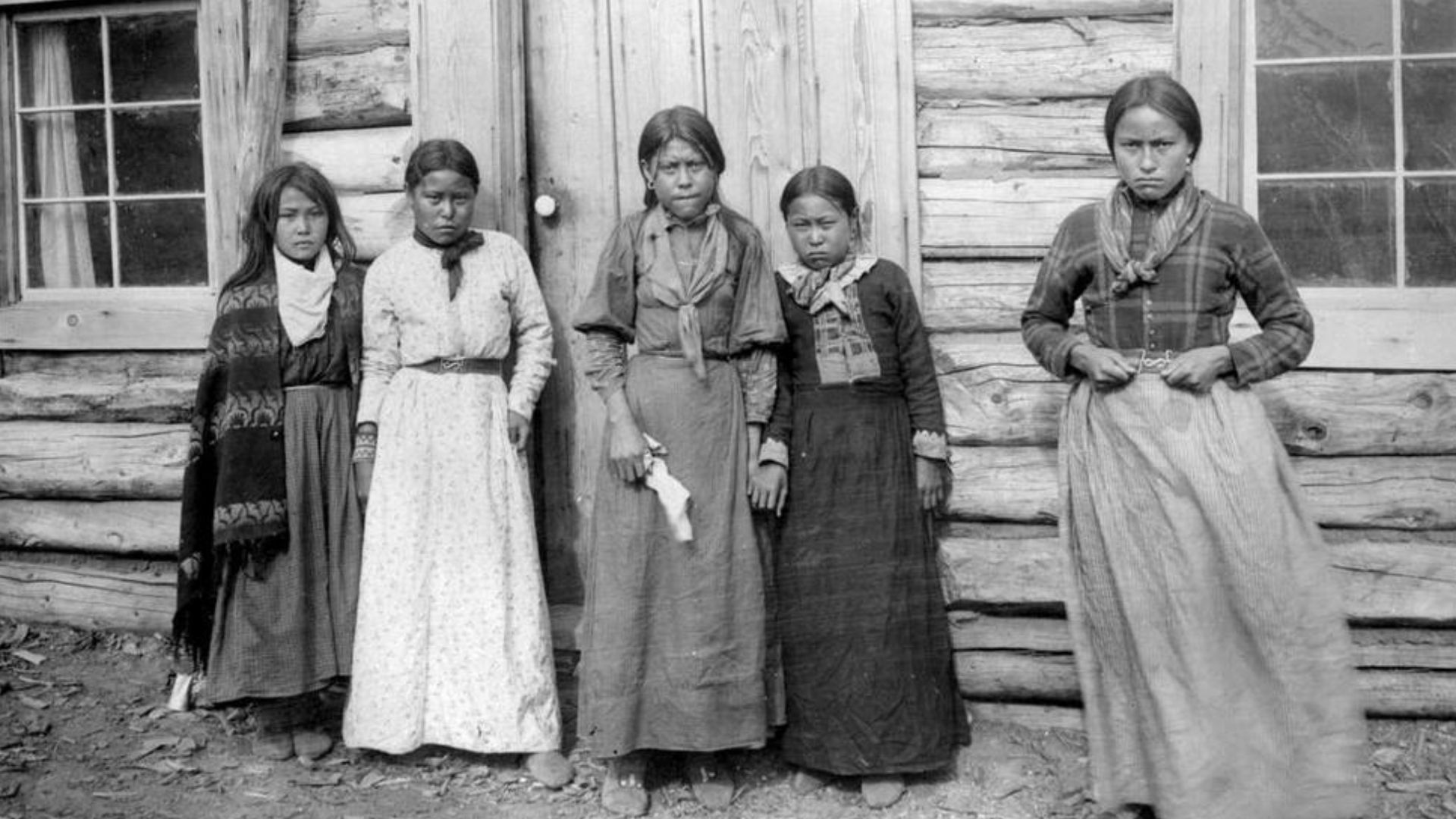

Andrew Jackson Stone, Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Jackson Stone, Wikimedia Commons

How Did They Look And Live?

Tahltan people traditionally wore garments made from animal hides. Their appearance—moccasins, woven blankets, and beaded accessories (some post-contact) were common. The Tahltan lived in communal dwellings during summer fishing seasons and lean-to shelters during winter hunts. Their architecture was made from spruce and pine poles with bark roofs.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

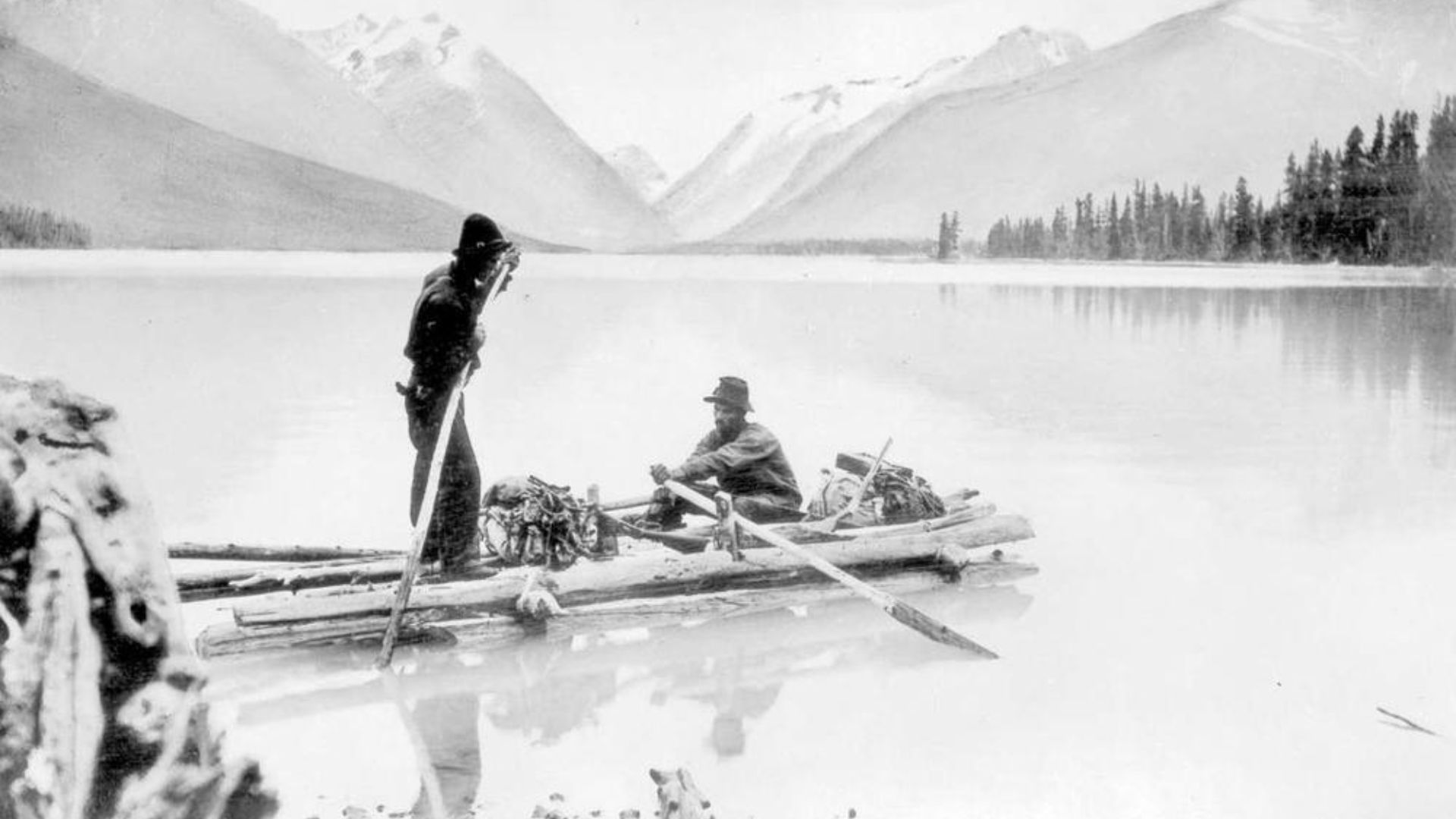

What Did They Do?

This lot had skilled hunters, fishers, and traders. They spent summers in large villages where salmon was smoked and preserved, and winters in dispersed family camps for trapping and hunting. Obsidian from Mount Edziza was a cornerstone of their economy—used to craft blades and exchanged across vast trade networks.

Andrew Jackson Stone, Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Jackson Stone, Wikimedia Commons

Who Were The Main Members Of The Community?

Tahltan society was divided into two main clans: the Crow (Tsesk’iya) and the Wolf (Ch’ioyone). Each clan had hereditary chiefs, family leaders, and ceremonial roles. Women held significant power, passing down names and property. Clan leaders managed hunting territories and resolved disputes, while elders preserved oral traditions and spiritual knowledge.

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

Who Probably Owned The Bundle

The leather-wrapped bundle found in Mount Edziza possibly belonged to someone with ceremonial duties, such as a clan leader or elder; its construction suggests it may have been a sacred offering, maybe marking a seasonal rite or honoring the spirits of the land.

The Tahltan Today

Today, the Tahltan Nation continues to thrive, represented by the Tahltan and Iskut First Nations. They are stewards of their territory, defenders of cultural heritage, and leaders in Indigenous governance—evolving from ancient alpine hunters into contemporary guardians of tradition and land. Now back to the bundle uncovered recently.

The Leather Bundle Was Unique

This find contained no stone tools or durable materials typically associated with ancient artifacts. Instead, it was composed entirely of animal hide and wooden sticks. The absence of utilitarian components was unusual, and because of that, it suggested some intention—was it symbolic or the perfect icy accident?

The Wrapping Was Intentional

The animal hide had been tightly wrapped around the sticks to form a compact and deliberate structure. The thing about leather is that over time, it hardens naturally. Here, centuries later, that same property was observed, and it evidently shielded the interior from environmental decay since the inside remained intact.

David Palazón, Tatoli Ba Kultura, Wikimedia Commons

David Palazón, Tatoli Ba Kultura, Wikimedia Commons

The Sticks Were Also Not A Random Collection

Inside the bundle, the wooden sticks were uniform, meaning deliberate shaping could have taken place before the burial. Some were even peeled. Their alignment suggested a purposeful arrangement, possibly ceremonial or ritualistic. If only they could talk, they would tell us exactly their use.

The Sticks Bore No Evidence Of Practical Use

If a stick were a weapon, it would have been sharp, right? And perhaps spoon-shaped if it were for eating or cooking! Here, this collection bore no marks of wear—no chipping, sharpening, or abrasion. Their smooth surfaces and consistent dimensions led researchers away from utilitarian interpretations.

The open draft, Wikimedia Commons

The open draft, Wikimedia Commons

The Positioning Was Also A Point To Note

The bundle was found lying horizontally in the marsh, oriented toward a nearby body of water. This specific placement may hint at intentional positioning, potentially linked to ritual geography in broader Indigenous contexts where water and wetlands were seen as liminal spaces—thresholds between the physical world and spiritual realms.

British Columbia Department of Mines, Wikimedia Commons

British Columbia Department of Mines, Wikimedia Commons

Mount Edziza Seems Like The Ideal Liminal Landscape Of Meaning

Mount Edziza’s volcanic terrain and high-altitude wetlands have long held ceremonial value for the Tahltan people. These terrains are not merely ecological zones but feasible spiritual corridors, reinforcing that this find may be a sacred offering from the Tahltan Central Government (2021) and The Narwhal (2021).

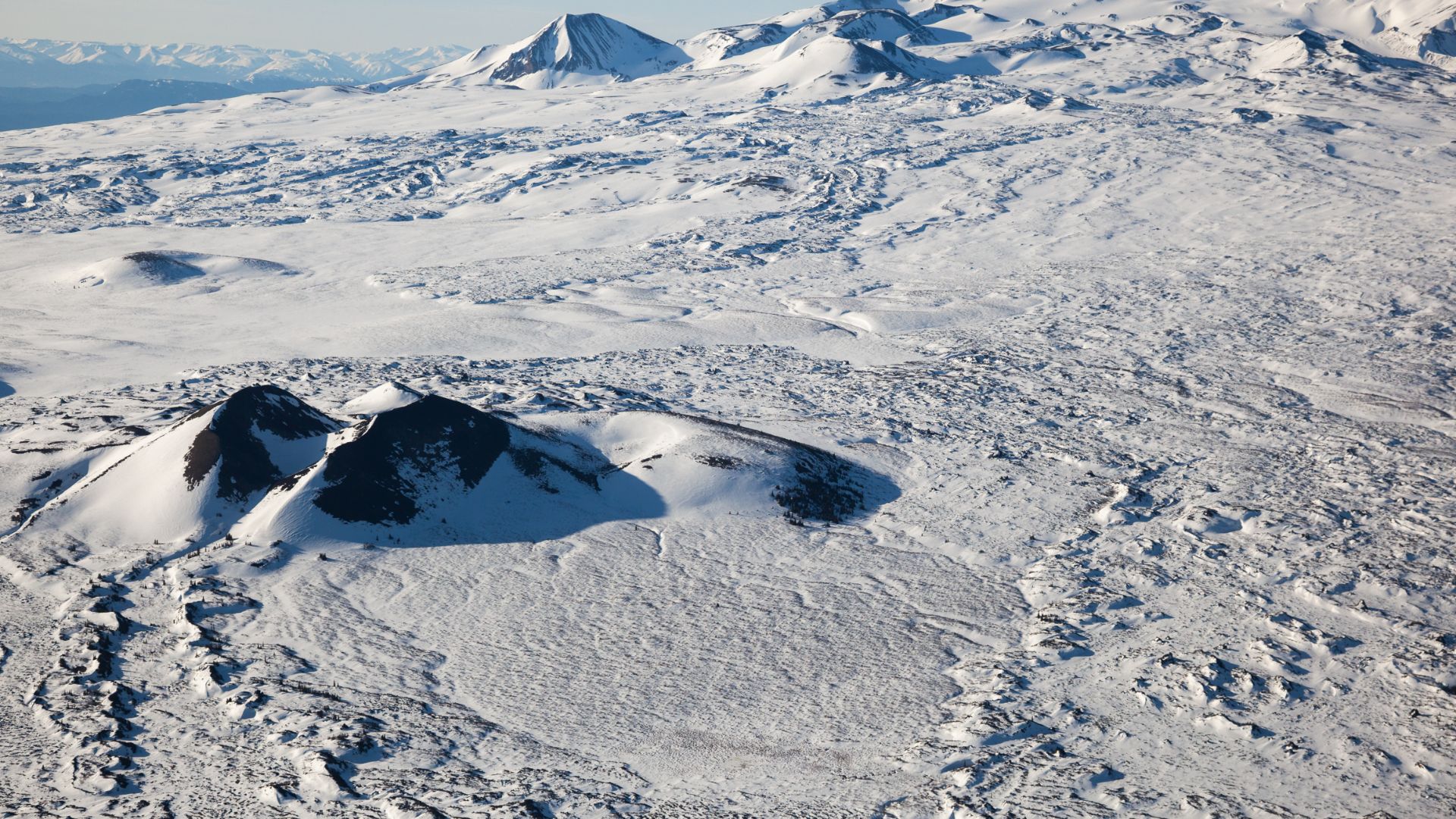

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

The Bundle Was Part Of A Larger Archaeological Pattern

This bundle was not one or two, but one of 56 perishable artifacts recently uncovered in Mount Edziza’s melting ice patches. The other items that the ice uncovered included birch bark containers, stitched hide boots, antler tools, and more, we are about to get into—some dating back over 7,000 years.

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

First, The Birch Bark Containers

Birch bark was a prized material back then. It was lightweight, waterproof, and pliable. Two standout birch bark containers were found among the perishable artifacts. One, dating back approximately 2,000 years, was folded with two rows of visible stitching along one side.

Doug Coldwell, Wikimedia Commons

Doug Coldwell, Wikimedia Commons

These Were No Ordinary Containers

The stitching material, likely sinew or plant fiber, was still preserved in some of the holes, showcasing the artisan’s skill and the container’s durability. The other container, estimated to be over 1,400 years old, had sticks stitched into its sides, maybe a reinforced basket to carry heavier loads.

Then, The Stitched Hide Boots

The hide boots were remarkably dated, approximately 6,200 years old. These were stitched from varying thicknesses of animal skin to reflect the ingenuity of early alpine travelers. These boots were evidently tailored to withstand the demands of moving in that mountainous terrain and keep one warm in that icy climate.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

The Antler Ice Picks

A 5,300-year-old antler tool with a sharpened point and hammer-like end was also among the 56. Their uses? Just two (maybe three): For navigating ice, crafting other tools….and maybe rituals. Antler, a renewable resource, was valued for its strength and versatility, and in these regions, it was a survival tool.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Walking Staffs

The wooden staff’s function appears obvious; hiking aids. But just hold that thought because beyond walking aids, staffs may have been symbolic in Indigenous traditions; perhaps for ceremonial or status markers. Could it be that the owners were traveling on spiritual journeys? Moving through sacred terrain or marking realm boundaries?

Jakub Hałun, Wikimedia Commons

Jakub Hałun, Wikimedia Commons

Projectile Shafts

Purported to once be part of arrows or spears, these shafts were straight, balanced, and durable, for accuracy and survival. But beyond utility, projectile weapons could feasibly be tied to rites of passage or seasonal hunting excursions. They could mark hunting camps or ceremonial deposits honoring successful hunts.

Obsidian Artifacts

Mount Edziza is rich in obsidian, a volcanic glass that’s beautiful to look at. This means that the Tahltan’s ancestors made obsidian items for trade or adornment. Obsidian is also sharp, perfect for making cutting tools. The abundance of obsidian tools and flakes found indicates it was a major quarry site.

Everything Else Included

Fragments of cordage—twisted plant fibers or sinew—were also found here. Some artifacts resembled frames or shallow containers. There were also scattered remains of animal bone or broken tools and a few unidentified organic objects. All these clearly had a function which we have yet to uncover.

Marco Chemello (WMIT), Wikimedia Commons

Marco Chemello (WMIT), Wikimedia Commons

Toward Cultural Reclamation And Stewardship

The Tahltan Nation is now working to preserve and interpret these finds, with ongoing plans for a museum in their territory. The bundle and all the other artifacts are housed in climate-controlled conditions to ensure their longevity. More than relics, they are vessels of memory.

Richard N Horne, CC BY-SA 4.0,Wikimedia Commons

Richard N Horne, CC BY-SA 4.0,Wikimedia Commons