A Golden Era

Off the coast of Israel, a diver discovered a gold coin, the first of over 2,000 to be found. He could see Arabic script on the coin, which had plunged into the Mediterranean near Caesarea, named after the Roman emperor. Media hype said the discovery rewrote history. But did it?

Beneath The Surface

The coins are genuine, and they’re no fool’s gold. But the claim they’ve overturned historical assumptions perhaps goes a bit far. So let’s look at the undisputed facts, the various interpretations, and what we really do know or don’t know about Ceasarea and its waters.

A Taste Of History

Scuba diver Zvika Fayer was in the depths when he saw a wrapper, the kind that encases edible chocolate coins. Nearing the flickering glow, he realized what it was: a real gold coin. Pushing away the sand, he saw more of them—and this was no chocolate. This was history.

Israel’s Ancient Underwater Treasure: The Caesarea Gold Coin Discovery, Lahiru sankalpa

Israel’s Ancient Underwater Treasure: The Caesarea Gold Coin Discovery, Lahiru sankalpa

In The Deep Blue Sea

It was early 2015, and Fayer and his friends were doing what they liked best: swimming among the fishes and submerged ruins of long-past history. This was perfectly legal, as Israel’s government allows such exploration of many archaeological zones beneath the sea.

Israel’s Ancient Underwater Treasure: The Caesarea Gold Coin Discovery, Lahiru sankalpa

Israel’s Ancient Underwater Treasure: The Caesarea Gold Coin Discovery, Lahiru sankalpa

Golden Hour

A tremendous storm had hit Caesarea the night before, lashing the ancient port city and stirring up the depths of the nearby Mediterranean. It was within these depths that Fayer gazed at the artifacts with increasing astonishment. He could see they were real gold, and had Arabic writing.

In The Beginning

Historians knew the port town had started around the 4th century BC as a place where Phoenicians and Greeks could trade. Then, Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, took it over in the 1st century BC. And then the Romans showed up, with their love of constructing roads and more.

Paying Tribute

An empire needs its middle management, so the Romans gave the region to biblical baddie Herod the Great, who gratefully changed the port’s name from Straton’s Tower to Caesarea, a nice little tribute to Roman dictator Julius Caesar. And infrastructure projects followed.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

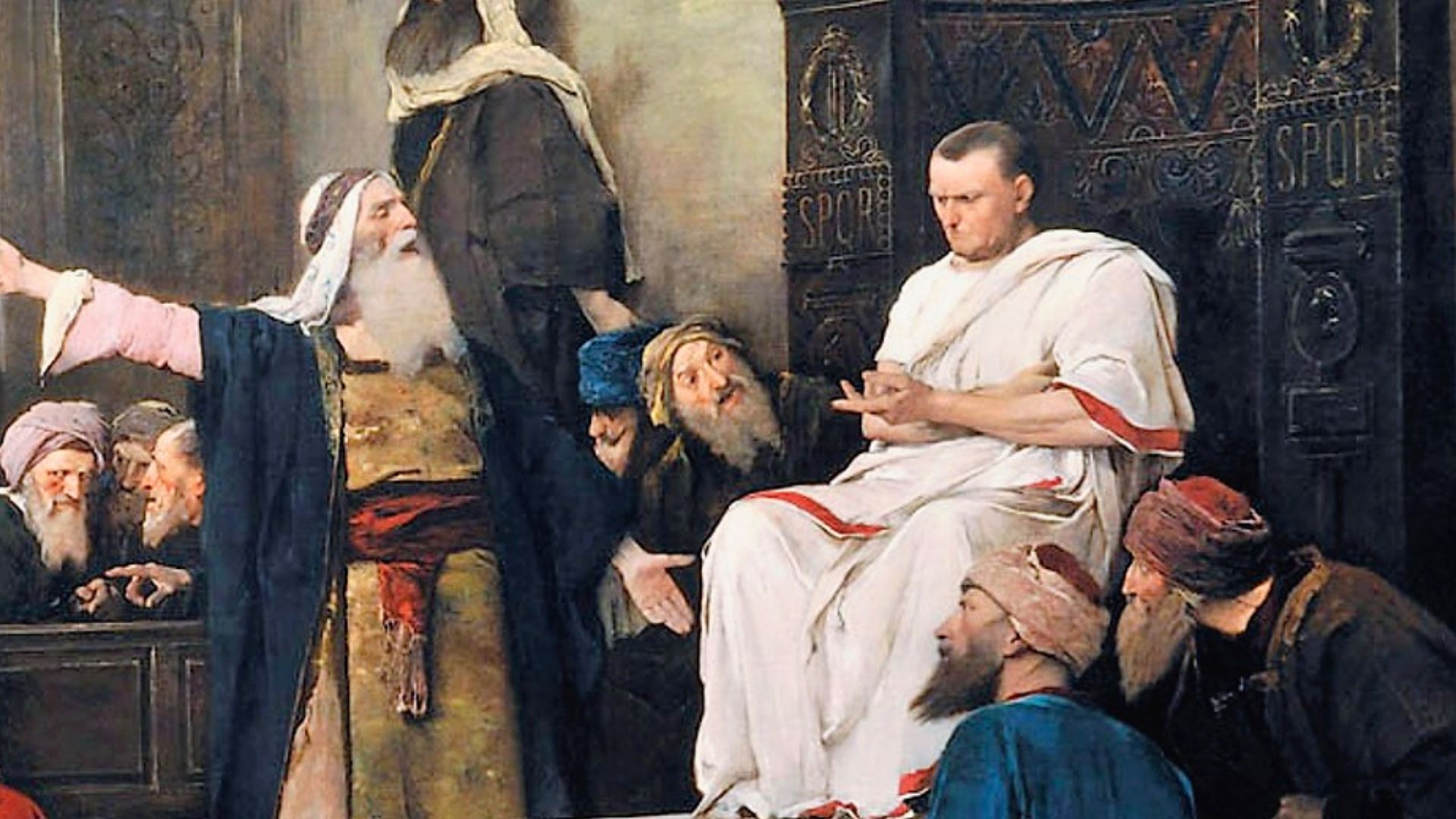

Expansion Project

Herod ordered breakwalls for a larger harbor, and gave the city a race track and amphitheatre. After Caesarea became Judea’s capital, another biblical baddie, Pontius Pilate, called it home. And after the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in AD 70, Caesarea grew even more important.

Mihály Munkácsy, Wikimedia Commons

Mihály Munkácsy, Wikimedia Commons

Unrecorded History

But nothing is forever. The Roman Empire fell, Muslim invaders took over Caesarea in AD 640, and (says one article) historians assumed the port withered, save for looters checking out ruins, and then fishermen who took up residence in the 19th century. But the gold coins say otherwise.

Shout It Out

But first, Fayer had to get archaeologists to take notice. He had no intention of squirrelling away the coins for himself, so he and his friends called city officials, who contacted the Israeli Antiquities Authority (IAA), who turned out to be a little hot under the collar. They started yelling.

Carpioco Silvia, Wikimedia Commons

Carpioco Silvia, Wikimedia Commons

Stormy Weather

According to Fayer, the archaeologists berated them for bringing the coins up to the surface. Fayer and friends explained how one storm had dislodged the coins, but another storm could bury the coins again—in fact, a bad storm was already approaching. The IAA calmed down.

Ancient Treasures Discovered Off Coast of Caesarea, CBN Israel

Ancient Treasures Discovered Off Coast of Caesarea, CBN Israel

Retrieval Mission

Fayer and his friends were allowed to go back underwater and bring back more coins, and then even more a few days after that. Eventually, the count exceeded 2,000 coins, and they were in incredible shape. The 24-karat gold coins had a 95% purity and dated to 1,000 years ago.

The Caesarea Gold Treasure, israelarchaeology

The Caesarea Gold Treasure, israelarchaeology

Coins Of The Realm

And who has coins like that? Not country bumpkins of the caliphate. It looked like some cosmopolitan trading was going on here. Analysis showed the coins were minted in Cairo and Palermo, and neither Egypt nor Sicily were next door. But both places belonged to an empire.

Ancient Treasures Discovered Off Coast of Caesarea, CBN Israel

Ancient Treasures Discovered Off Coast of Caesarea, CBN Israel

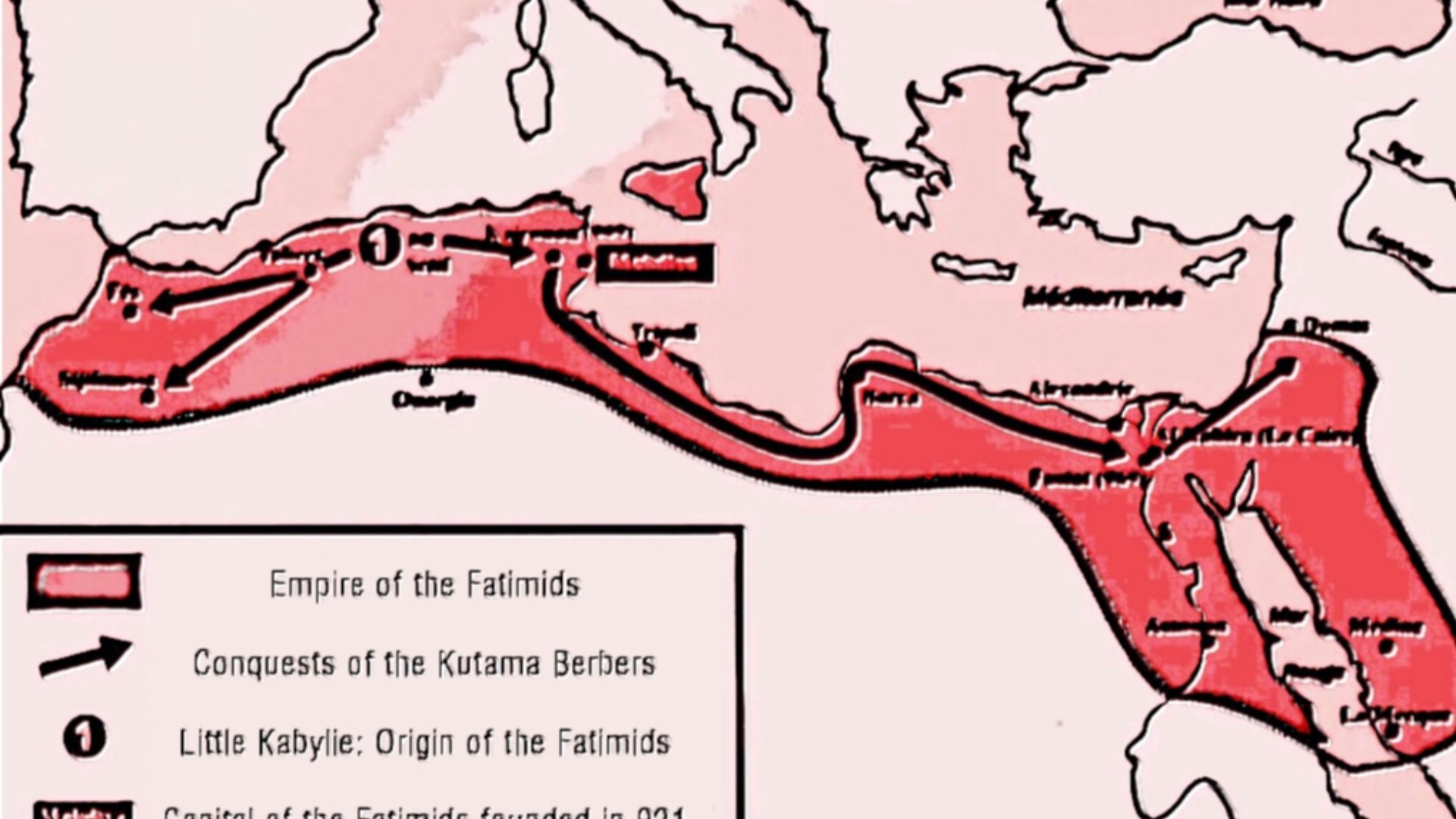

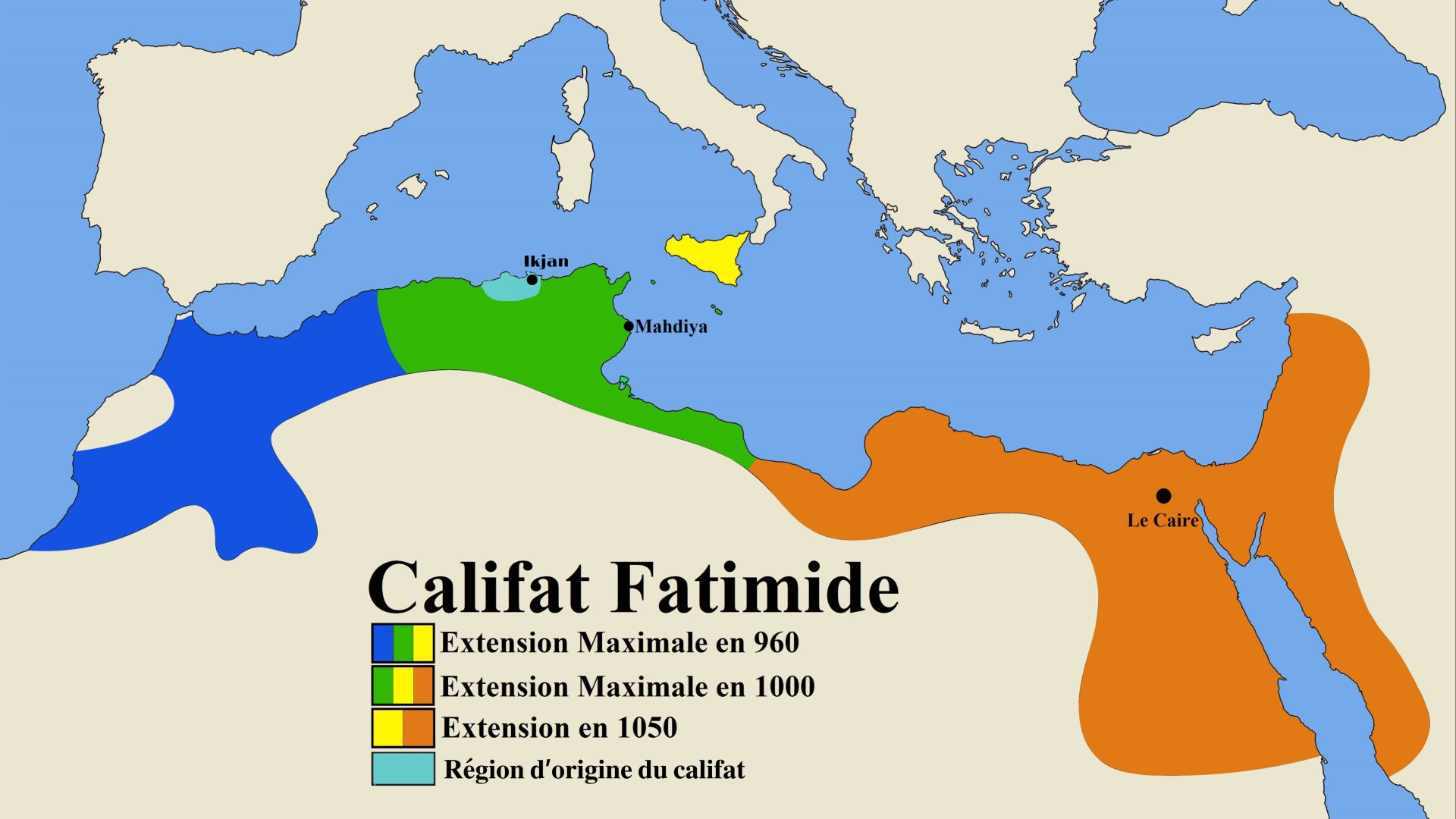

The Sicilian Connection

Around AD 1000, the Islamic Fatimid Dynasty owned some serious real estate in the Eastern Mediterranean, which helps explain the Egyptian and Sicilian connections. When the coins weren’t dropping into the sea, the townsfolk of Caesarea must’ve been pocketing a lot of them.

Death And Taxes

One dinar would pay a soldier for a month, so 2,000 of these coins would pay for a small army. Or maybe buy some foodstuffs or nice luxury goods. But another theory notes that Cairo was central HQ for the Fatimid government, so a ship could’ve been on its way to fork over taxes.

Safe Storage

It’s also possible the good folks of Caesarea were getting antsy as the threat of the Crusades loomed. Moving some of their wealth to safer regions might’ve been an important component of their financial planning. The absence of an actual shipwreck helps keep the question wide open.

Anchoring The Evidence

A nail and five untethered anchors were near the coins. The nail might have been part of a ship, or part of a chest that held this or some other bounty. But no big shipwreck was found. It’s also possible marauding pirates or a gusty storm knocked a treasure chest of coins overboard.

Ancient Treasures Discovered Off Coast of Caesarea, CBN Israel

Ancient Treasures Discovered Off Coast of Caesarea, CBN Israel

Trading Places

But these shiny dinars show that traders went to lots of places within the caliphate—and used the same currency to do so. And as buyers and sellers everywhere know, it’s important to be sure of what you’re getting. The coins showed toothmarks, a way to check if you’ve hit gold.

Israel’s Ancient Underwater Treasure: The Caesarea Gold Coin Discovery, Lahiru sankalpa

Israel’s Ancient Underwater Treasure: The Caesarea Gold Coin Discovery, Lahiru sankalpa

The Course Of History

And Caesarea isn’t doing too badly nowadays either. The coastal city offers tourists the chance to explore ancient ruins, visit a museum, and even hit the local greens to play some golf. You can ponder history as you pay for your drinks, not with gold dinars, but some paper shekels.

Revised Version

In between sips, think of how 2,000 coins helped to rewrite the story of Caesarea after it fell to Muslim invaders. With records hard to come by, it seemed the port had become just an obscure little village at best. But these shimmering gold coins have uncovered a much richer history.

ABRAHAM GRAICER, Wikimedia Commons

ABRAHAM GRAICER, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Change

But is this media hype? A BBC article quotes an IAA official as saying, “Before finding the coins, we had no idea that the community in Caesarea at that time was so large or so rich. So it changed what we believed about that time”. And the article makes some other startling claims.

Backwater Reputation

The article says that after 640, “records are spotty,” but “Caesarea faded from glory”—or so it was believed. The discovery of the coins “changed that story,” and refutes the idea the city turned into a backwater. But is that so? A lot was known before the coins, so let’s return to 640.

On A Roll

The Rashidun Caliphate was on a roll in the 630s. Islam’s founder, Muhammad, died in 632, but not before clashing with the Byzantine Empire—the eastern part of the old Roman Empire. Soon, Muhammad’s successors, Abu Bakr and later Umar ibn al-Khattab, launched a full-scale war.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Overshadowing Jerusalem

The Byzantine Empire was Christian, and Caesarea had become a major center of local church power and learning. For a while, it even had jurisdiction over Jerusalem, though Caesarea got demoted in 451. But the coastal town remained the provincial capital of Palaestina Prima.

The First Incursion

Things got dicey in the early 600s. The Sassanid Persians hit the Byzantines from 602 to 628, and in 614, they managed to take over Caesarea. The Byzantines managed to retake the city in 625, but their success was short-lived. In 640, a new attack—from Arab ranks—succeeded.

Piero della Francesca, Wikimedia Commons

Piero della Francesca, Wikimedia Commons

Signs Of Destruction

Archaeologists point to a “destruction layer” in the soil that may reflect the damage inflicted by both Muslim conquests, though there’s some debate about that. There’s also evidence some 4,000 captives were sent to Caliph Umar to be assigned as slaves throughout the Islamic empire.

The Waiting Game

The city was absorbed into the Rashidun Caliphate, though with far fewer residents. The population might have seen an uptick during the Umayyad Caliphate, with evidence of farming in the 11th century—before the Crusaders showed up. And that brings us back to the coins.

FamilyPedia - Wikia, Wikimedia Commons

FamilyPedia - Wikia, Wikimedia Commons

Quite A Sight

The gold coins feature two rulers, al-Hakim and son al-Zahir, spanning reigns from 996 to 1036. Even if the coins are sensational, how much more do they tell us about Caesarea before the Crusaders showed up? After all, we already have one description of this “fine city” from 1047.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

What Decline?

Nasir Khusraw was an Isma'ili poet and missionary for the Fatimid Caliphate. He described “running waters” and “palm-gardens,” along with strong walls and an iron gate. This doesn’t sound like a city in decline, but more like a major urban center fortified against all threats.

Rassam Arjangi, Wikimedia Commons

Rassam Arjangi, Wikimedia Commons

On A Crusade

Then, the Crusaders arrived. William of Tyre wrote the city was fortified enough that the invaders had to use catapults and other equipment to break down the defenses. It was 1101, and the Crusaders triumphed, looting the city, killing the men, and enslaving the women and children.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Back And Forth

The Crusaders turned the mosque into a church, and the Latin See of Caesarea was set up with 10 archbishops. Saladin, vowing to retake the infidels’ conquests, entered the city in 1187, but the Third Crusade pushed his forces out in 1191. More Crusades followed, and more threats.

Final Defeat

During the Seventh Crusade, in 1251, Louis IX ordered wall and moat fortifications. But it wasn’t enough. The Mamluk Empire, Muslim rulers of Egypt, became the new threat. In 1265, Sultan Baibars launched an all-out offensive on the city. Victorious, he ordered the city destroyed.

Guillaume de Saint-Pathus, Vie et miracles de Saint Louis, Wikimedia Commons

Guillaume de Saint-Pathus, Vie et miracles de Saint Louis, Wikimedia Commons

Off The Map

And the destruction was massive. No one lived in the fortified town or the Roman ruins for a long time. The Ottoman Empire took over the area in 1516, and a 1664 record mentions about 100 families. In the early 19th century, a traveler noted a few fishermen and their families.

Shining A Light

So, what do the coins really show? Excavations in the eastern part of the Fatimid Empire had been going on for quite a while, as the researchers’ preliminary paper notes. It was well known before the Caesarea find that gold dinars and part dinars dominated the empire’s coinage.

Ademdefrance, Wikimedia Commons

Ademdefrance, Wikimedia Commons

Worth The Visit

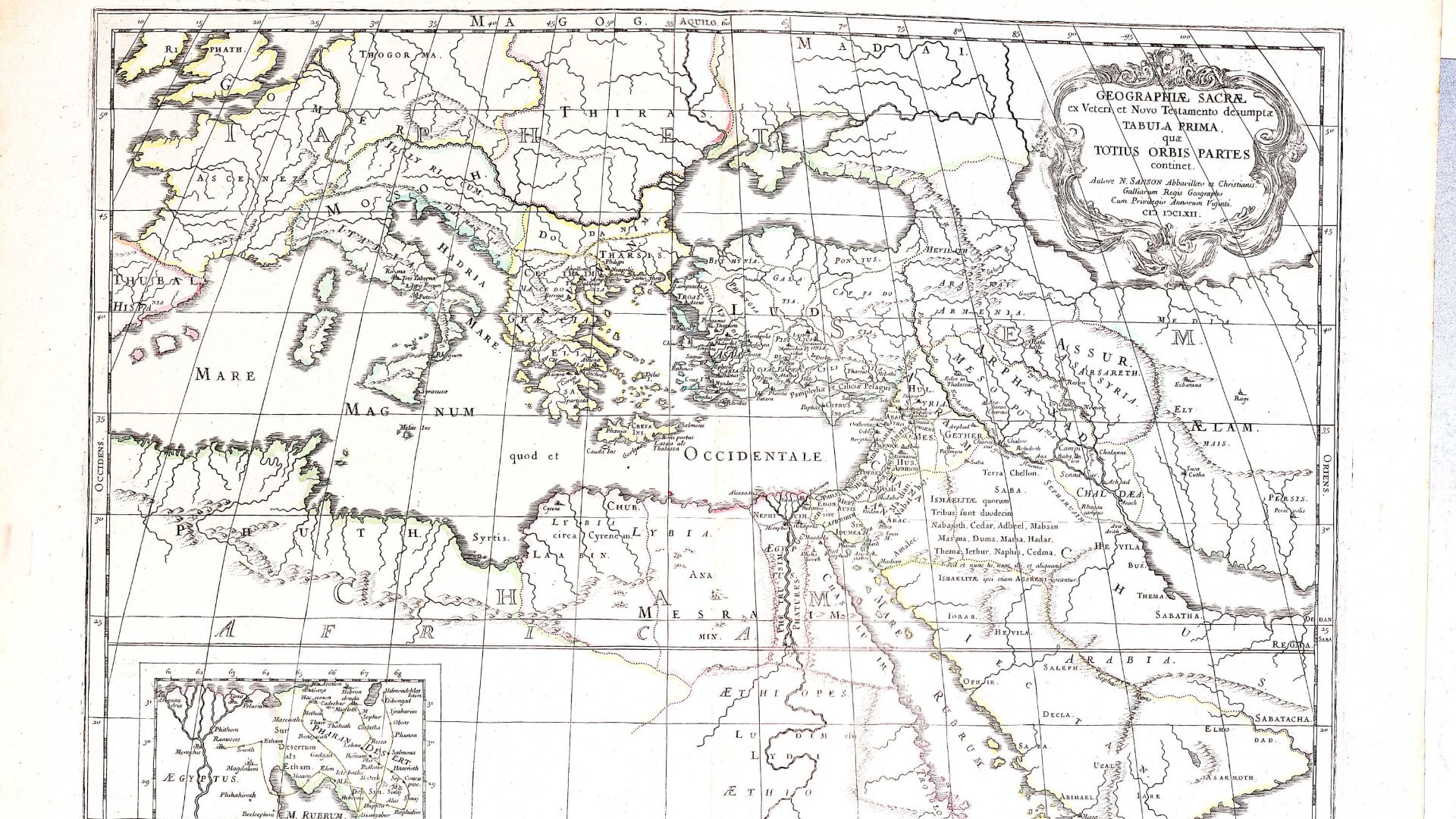

The “wealth and opulence” of Fatimid Cairo was also well documented, the paper acknowledges, with the empire’s coins making their way from North Africa to the eastern Mediterranean and back again. Trade was clearly a vital part of forging imperial prosperity.

Nicolas Sanson, Wikimedia Commons

Nicolas Sanson, Wikimedia Commons

Dinar Data

But 7.5 kg (16.5 lbs) of gold do provide a lot of data points on where coins were minted, ranging from North Africa to Yemen. But most were produced at four mints in Sicily, Tunisia, and Egypt. Where the gold for the coins came from is something that can be researched a lot more, though.

Finding The Source

The gold likely came mostly from the Kingdom of Ghana and a region that included Upper Egypt, but details are still to be determined. It’s a question that actual coins can help answer, filling in the gaps of documentation lost or never written to begin with. So, the coins do matter.

Not So Shabby

As for the history of Caesarea, the researchers note the Islamic conquests and the decline in population, but also mention the fortifications. There’s also archaeological evidence for the prosperity of the town in the 10th and 11th centuries, from brass objects and gold hoards.

Fall And Rise

So, there’s just not a lot of evidence that Caesarea was some “backwater” after 640. It’s possible the offending article mistakes the decline after the Crusaders were decisively defeated—after the time of the coins—for the period between the first Islamic conquests and the Crusades.

Unknown, 13th-century author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown, 13th-century author, Wikimedia Commons

Both Sides Of The Coin

So, even if the coins didn’t revolutionize our historical understanding of Caesarea, they do cast some golden shimmering light on the wealth of Caesarea and the Fatimid Empire it belonged to. It’s been a golden ticket to learn more, stirring up interest in an intriguing and long-ago era.

You May Also Like:

The Discovery Of A Sunken Japanese "Hell Ship"

The Priceless Treasures Of The Palmwood Shipwreck