Brittany's Sunken Past

Laser mapping revealed geometry where chaos should reign on the seafloor. Divers descended into cold Atlantic darkness and found organized rows of standing stones. These were coastal communities doing the impossible, and they were doing it centuries too early.

Seabed Anomaly

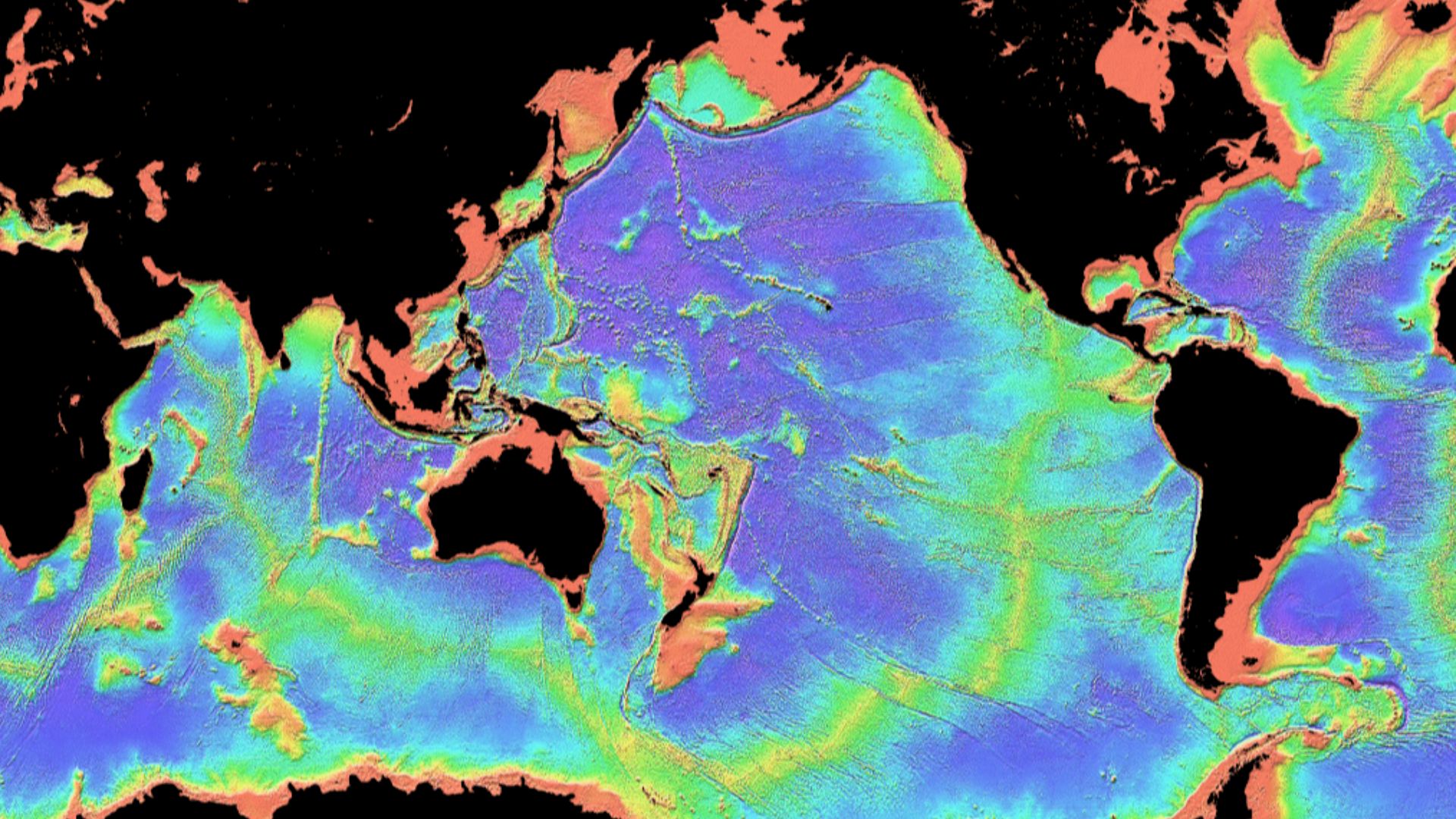

Retired geologist Yves Fouquet wasn't searching for ancient monuments when he scanned the latest seabed charts in 2017. He was simply studying the ocean floor off Ile de Sein. Then his eyes caught a perfectly straight line slicing across an underwater valley for nearly 400 feet.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Wikimedia Commons

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Wikimedia Commons

LIDAR Mapping

The breakthrough came through laser technology that pierces water to reveal what lies beneath. LIDAR bathymetry turned the murky depths of the Atlantic into crystal-clear digital maps, revealing geometric patterns on the seafloor that traditional sonar would have missed entirely. The linear anomaly Fouquet discovered measured exactly 120 meters long.

NOAA Ocean Exploration & Research, Wikimedia Commons

NOAA Ocean Exploration & Research, Wikimedia Commons

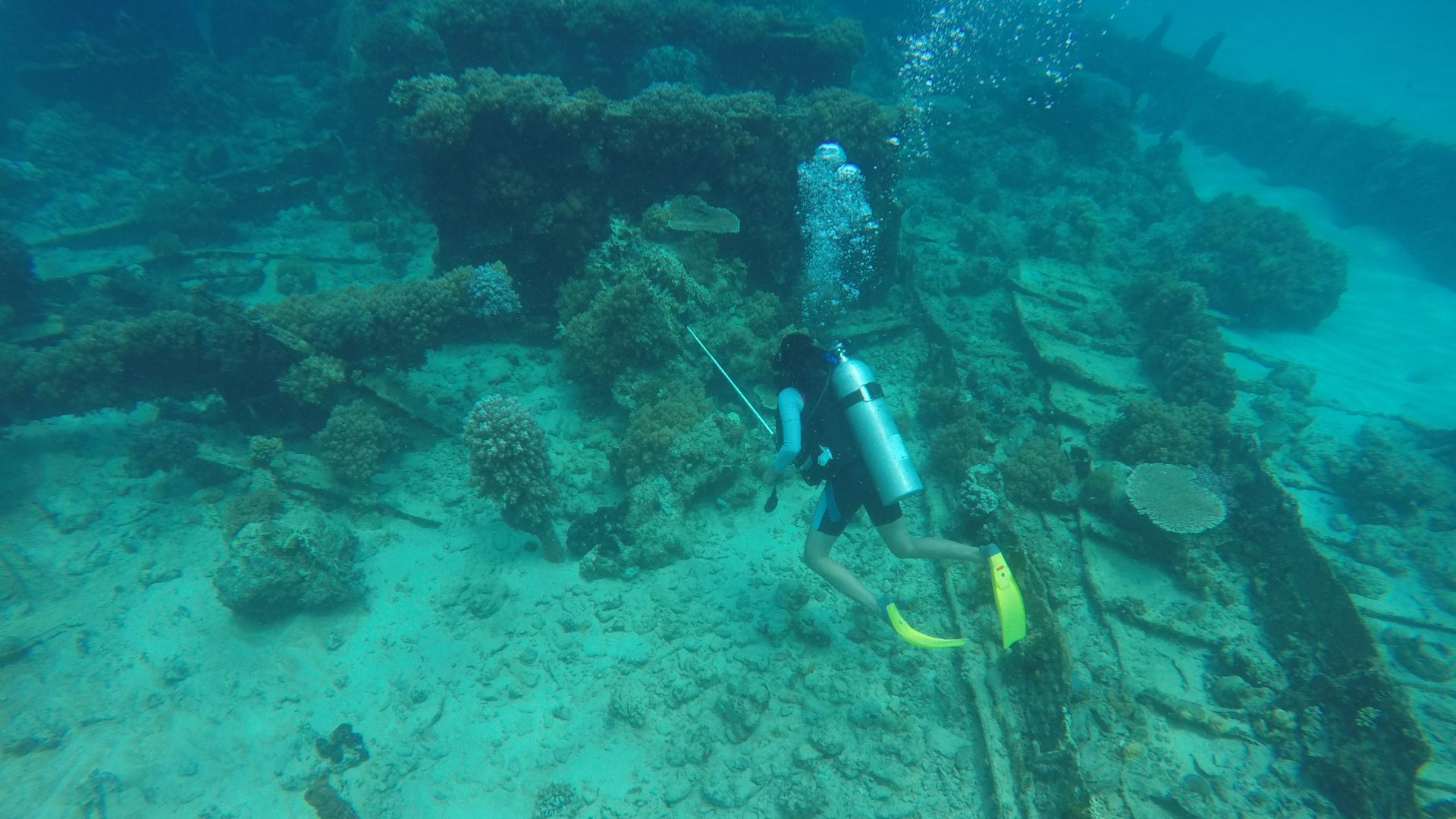

Diving Expeditions

Between 2022 and 2024, ten divers from the Societe d'Archeologie et de Memoire Maritime conducted 59 separate dives into the cold, turbulent waters. Timing was everything—they could only work during the winter months when dying seaweed improved underwater visibility from nearly zero to workable conditions.

Dwi sumaiyyah makmur, Wikimedia Commons

Dwi sumaiyyah makmur, Wikimedia Commons

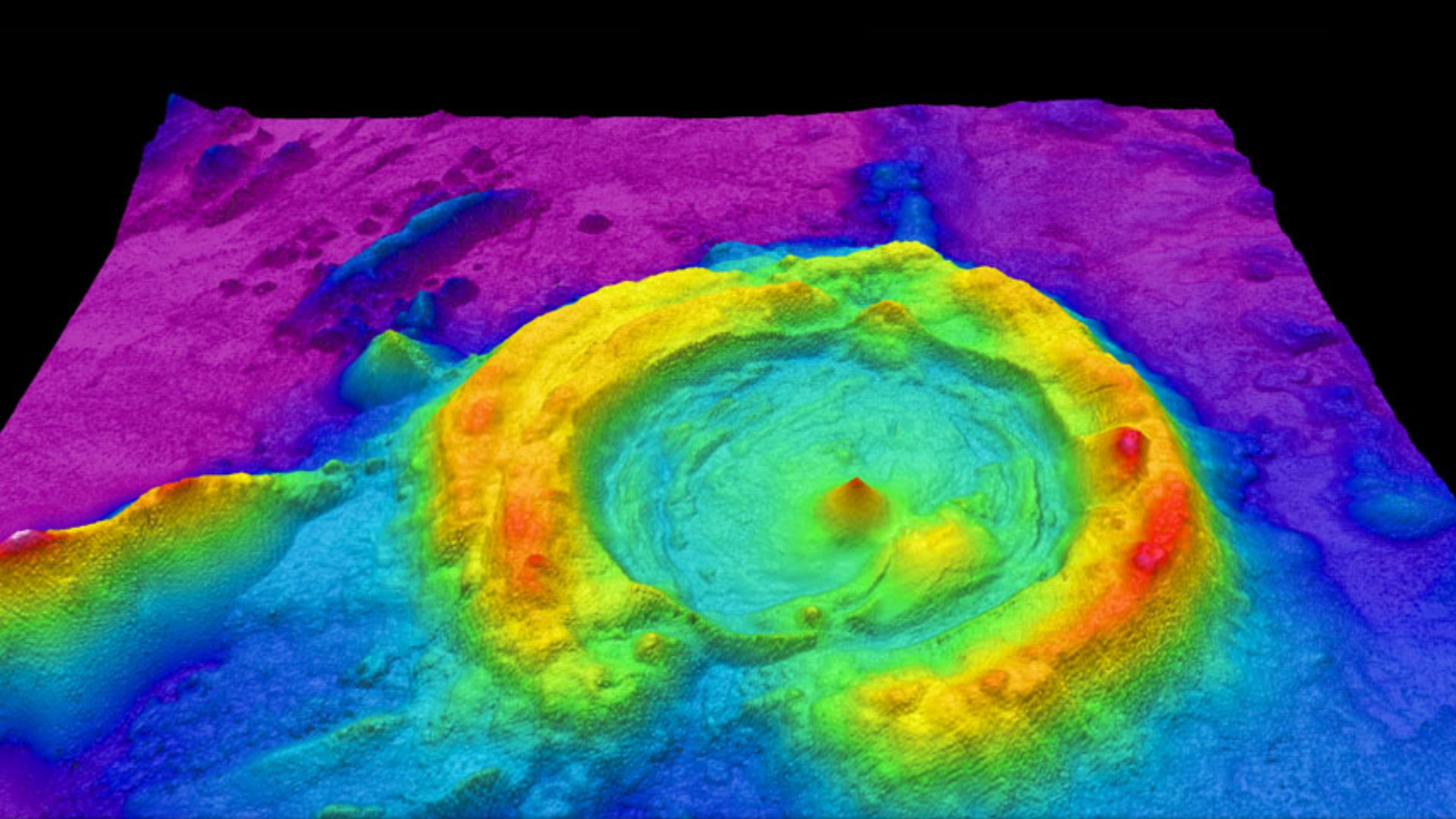

Granite Structure

What emerged from the depths defied all predictions: a massive wall averaging 20 meters wide at its base and standing up to 2.1 meters tall. The structure contains approximately 3,300 tons of carefully stacked granite blocks, each weighing several hundred kilos.

Dwi sumaiyyah makmur, Wikimedia Commons

Dwi sumaiyyah makmur, Wikimedia Commons

Monolith Rows

Rising from the wall's crest, more than 60 upright standing stones pierce through the stacked granite like sentinels frozen in time. These monoliths reach heights of 1.7 meters and are arranged in two parallel lines running the wall's entire length.

Construction Scale

Moving thousands of tons of granite without modern machinery required extraordinary planning, labor coordination, and probably months of sustained effort. The builders quarried 80% of the granite blocks from low-lying coastal areas, while the massive monoliths came from nearby reef formations.

Placement Precision

Every stone in the wall occupies its position with deliberate intent. The monoliths maintain consistent spacing and orientation along the entire 120-meter length, suggesting that the builders worked from a predetermined plan. Foundation stones were carefully selected for stability, with angular boulders wedged between larger slabs to create structural integrity.

NOAA (Maya Walton), Wikimedia Commons

NOAA (Maya Walton), Wikimedia Commons

Material Sources

Builders didn't simply use whatever rocks lay nearby. They deliberately selected specific granite types for different structural purposes. Small vertical slabs came from a single quarry, while the impressive monoliths originated from exposed reef outcrops that required specialized extraction techniques.

Bathtub brainstormer, Wikimedia Commons

Bathtub brainstormer, Wikimedia Commons

Dating Methods

Without organic materials like wood or bone for traditional radiocarbon dating, archaeologists turned to sea-level science for temporal answers. They used precise reconstructions of post-glacial sea-level rise in western Brittany to calculate exactly when the wall's current depth would have been in the intertidal zone.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center from Greenbelt, MD, USA, Wikimedia Commons

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center from Greenbelt, MD, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Approximately 7,500 Years

The wall was built between 5,800 and 5,300 BCE, making it one of Europe's oldest large-scale stone constructions. This timeframe places construction during a period of dramatic environmental change, when melting ice sheets raised sea levels at rates between 5.2 and 8.4 millimeters annually.

Roxanne Desgagnes roxannedesgagnes, Wikimedia Commons

Roxanne Desgagnes roxannedesgagnes, Wikimedia Commons

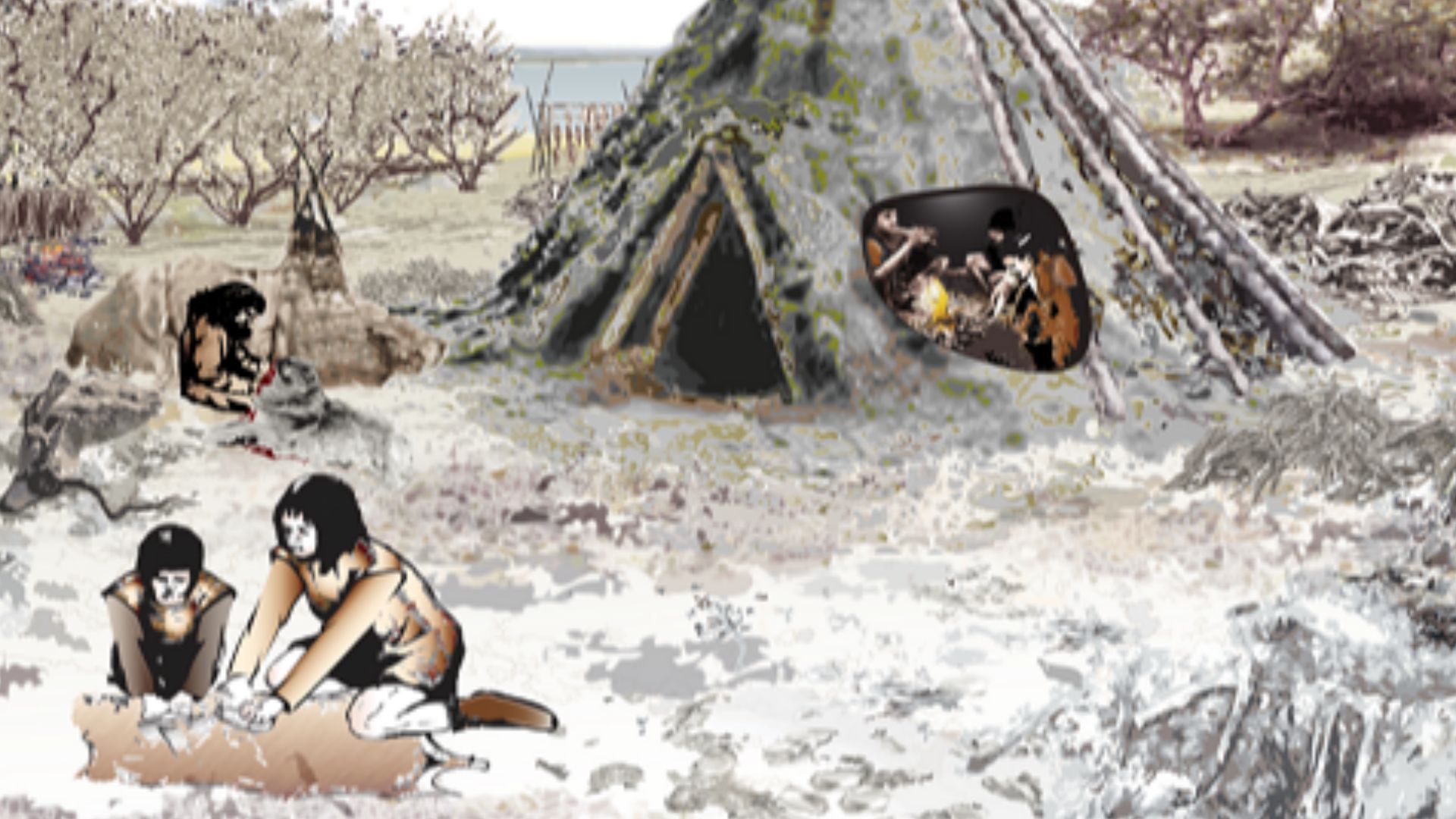

Mesolithic Period

The wall's construction falls at the twilight of the Mesolithic era, that "middle stone age" bridging Paleolithic cave dwellers and Neolithic farmers. Traditional archaeological thinking portrayed the people of this period as small, mobile bands with simple seasonal camps and minimal social hierarchy.

David Hawgood, Wikimedia Commons

David Hawgood, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Level

Global sea levels during the wall's construction sat roughly seven meters lower than today's Atlantic waterline. The last ice age's massive glaciers were still melting across North America and Scandinavia, feeding an inexorable rise that drowned coastlines worldwide. Brittany's coastal plains stretched far beyond current shorelines.

Pedro Lastra peterlaster, Wikimedia Commons

Pedro Lastra peterlaster, Wikimedia Commons

Hunter-Gatherer Societies

Rich archaeological evidence from nearby Hoedic and Teviec islands shows Mesolithic graves filled with shell ornaments, engraved bones, imported flint tools, and ochre pigments. These "fisher-gatherers" enjoyed sedentary or semi-sedentary lifestyles, returning seasonally to favored locations where shellfish, fish, and seabirds provided reliable sustenance.

Coastal Communities

The wall's builders weren't isolated primitives but participants in extensive maritime networks connecting Breton islands and mainland settlements. Evidence shows they mastered navigation through some of Europe's most dangerous waters, with powerful currents, dramatic tides, and sudden storms. Reaching Ile de Sein required sophisticated boat technology.

Social Organization

Building a 3,300-ton granite wall demands more than individual effort. It requires leadership, planning, task delegation, and sustained cooperation across months. Someone had to organize labor, coordinate quarrying operations across multiple locations, manage stone transport logistics, and direct construction in accordance with a unified design.

Colin Hunter, Wikimedia Commons

Colin Hunter, Wikimedia Commons

Technical Skills

Builders understood how to identify natural weaknesses in stone, where to insert wooden wedges, and how water expansion could split massive blocks. Transporting these giants across uneven coastal terrain demanded engineering solutions—likely wooden rollers, rope systems, lever arrangements, and carefully constructed pathways.

Fish Trap

One compelling theory interprets the wall as an elaborate coastal fish weir, a technology documented across northern European Mesolithic sites. The protruding monoliths could have supported frameworks of branches, sticks, and woven materials forming barriers and enclosures.

Gordon Leggett, Wikimedia Commons

Gordon Leggett, Wikimedia Commons

Tidal Engineering

Understanding tidal mechanics requires observational knowledge accumulated across generations of coastal living. The builders positioned their wall to exploit the dramatic tidal range characteristic of Brittany's Atlantic coast, where differences between high and low tide can exceed six meters. They calculated precisely where to place the structure.

Coastal Protection

The alternative hypothesis posits that the wall serves as defensive infrastructure against rising seas that threaten coastal settlements and lagoons. During the construction period, communities could literally watch the ocean advance inland within their lifetimes. Annual rises of 5 to 8 millimeters meant visible changes across decades.

Dual Theories

Archaeologists remain cautious about declaring a definitive purpose, acknowledging the wall might have served multiple functions simultaneously or different roles across its centuries of use. It could have operated as a fish trap during certain tidal conditions while also providing storm protection and territorial marking.

David Baird, Wikimedia Commons

David Baird, Wikimedia Commons

Carnac Comparison

Brittany's southern coast hosts over 3,000 standing stones at Carnac, stretching for 10 kilometers and representing the world's densest concentration of megalithic monuments. The submerged monoliths display striking similarities to Carnac's terrestrial menhirs with paired vertical stones, comparable heights, and deliberate spacing patterns.

Nicolas Raymond from Bethesda, Maryland, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Nicolas Raymond from Bethesda, Maryland, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Knowledge Transfer

The chronological overlap between the wall's construction and the arrival of Neolithic farming communities in Brittany raises fascinating questions about cultural transmission. Around 5,500–5,000 BCE, agricultural societies migrated into the region from continental Europe, encountering established Mesolithic coastal populations.

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

Megalithic Origins

Previously, scholars assumed monumental stone architecture emerged with Neolithic farming societies, tied to agricultural surplus and sedentary villages. This discovery proves that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers independently developed megalithic construction techniques, moving multi-ton stones and creating permanent monuments before agriculture reached Atlantic Europe.

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

Ys Legend

Local Breton folklore tells of Ys, a magnificent city swallowed by the Atlantic in the Bay of Douarnenez, just kilometers east of the wall's location. According to legend, King Gradlon ruled this prosperous coastal metropolis protected by massive dikes and gates until his daughter's folly unleashed the sea.