The Serpent Mountain Mystery

For nearly a century, 5,200 strange holes carved into a Peruvian mountainside baffled scientists worldwide. Wild theories emerged to include ancient aliens and lost civilizations. In 2025, archaeologists finally cracked the code that makes sense.

Bruno7, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Bruno7, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Gateway To Ancient Civilizations

Peru sits on South America's western edge, where the Pacific Ocean meets the towering Andes Mountains. This dramatic landscape of coastal plains and soaring peaks became home to some of history's most sophisticated civilizations—long before Europeans entered the picture.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

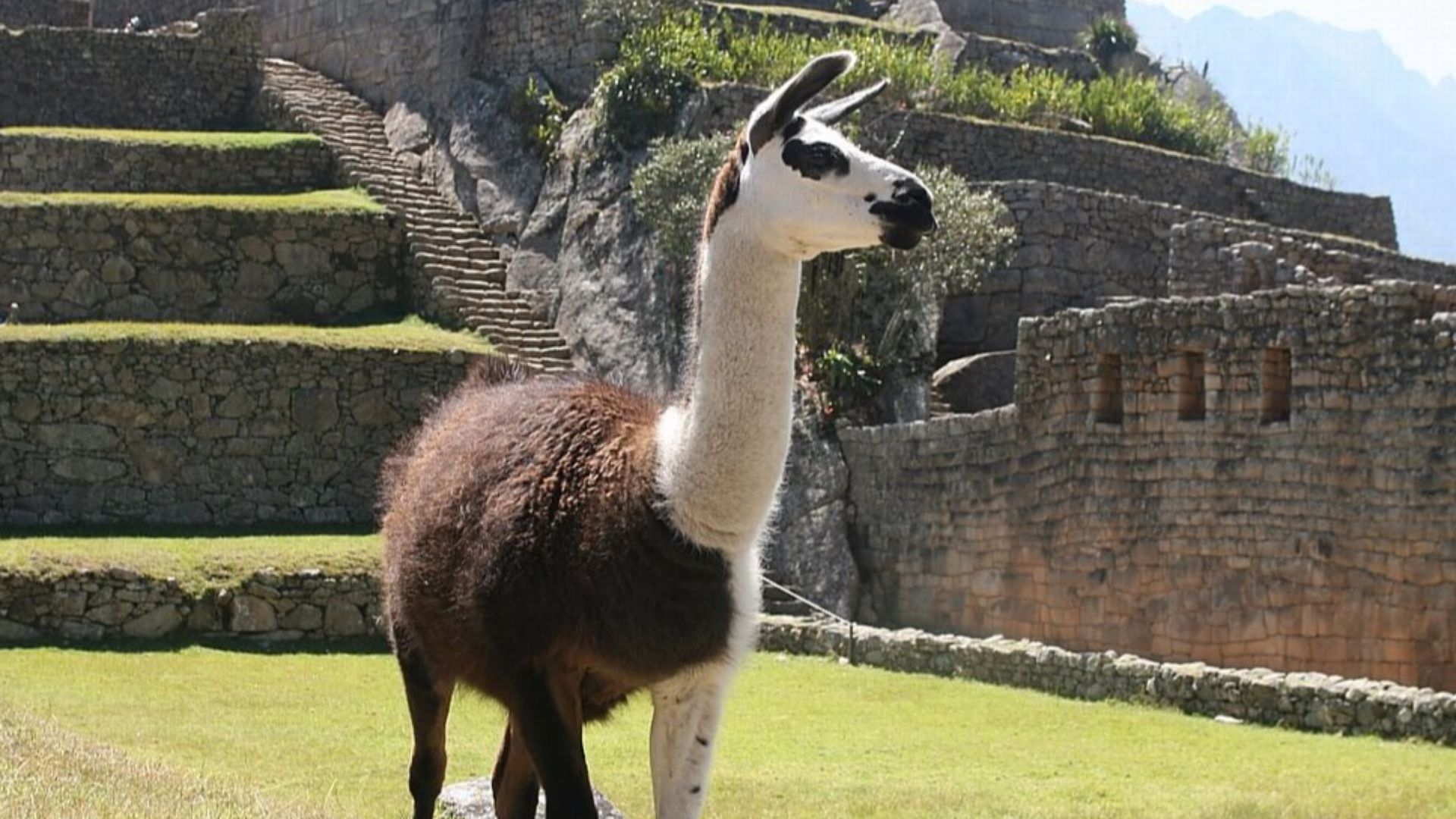

Peru's Archaeological Treasures

The place holds extraordinary ancient wonders: Machu Picchu's stone citadel perched in clouds, the massive Nazca Lines etched across desert floors, and Chan Chan's sprawling adobe city. Each site reveals ingenious societies that thrived with their unique abilities.

Martin St-Amant (S23678), Wikimedia Commons

Martin St-Amant (S23678), Wikimedia Commons

Where The Mystery Lies

The southern Pisco Valley marks the transition from Andean foothills to coastal plains, a fertile chaupiyunga zone where highlands meet the ocean. This rich environment nurtured ancient settlements and concealed a baffling mystery—thousands of enigmatic holes carved into the landscape.

Fer Quintana, Wikimedia Commons

Fer Quintana, Wikimedia Commons

First Sighting From Above

American geologist Robert Shippee and Lieutenant George Johnson soared above Peru in a small aircraft to photograph the landscapes below that contained the holes. They were quite precise in their shapes and depth, which made the mystery even more compelling.

TactualGalaxy, Wikimedia Commons

TactualGalaxy, Wikimedia Commons

The World Discovers The Mystery

Two years later, in 1933, the National Geographic Society published Shippee and Johnson's stunning aerial photographs. After the photographs were published, people started coming up with weird ideas and theories about what this could be. They wanted to know which civilization made this.

The Serpent Mountain

Locals called it Monte Sierpe—“Serpent Mountain”—because of the way it twisted along the ridge. The artificial band stretched about one mile long and ranged from roughly 46 to 72 feet wide. Visible from miles away, it dominated the landscape like a massive monument.

Staggering Numbers

Researchers counted approximately 5,200 individual holes. Each measured 1–2 meters wide and half a meter deep. The holes weren't randomly scattered. They formed roughly 60 distinct sections, separated by empty corridors like organized city blocks awaiting discovery.

Physical Characteristics Of The Holes

Workers had excavated each hole from natural hillside sediments. Some of these holes also featured partial stone wall linings for reinforcement. The sections were designed with a choice that suggested purposeful planning and mathematical organization, attributed to the intelligence of these people.

Why The Mystery Persisted

The remote Andean foothill location discouraged extensive expeditions. Even the ancient Andean peoples developed no writing system. Thus, it left no inscriptions or explanations carved in stone. Traditional ground-level archaeology couldn't comprehend the site's massive scale. The holes kept their secrets for decades.

nearsjasmine, Wikimedia Commons

nearsjasmine, Wikimedia Commons

The Research Drought

A lot of time went by with minimal investigation. The site's overwhelming scale defeated traditional archaeological methods. UCLA researcher Charles Stanish surveyed Monte Sierpe in the 2000s–2010s. In 2015, he proposed it functioned as an accounting or storage system, closer to the truth than anyone realized.

Aegis Maelstrom, Wikimedia Commons

Aegis Maelstrom, Wikimedia Commons

Modern Technology Arrives

Everything changed when drone technology matured in the 2010s. High-resolution aerial photogrammetry could now map entire archaeological sites in unprecedented detail. Drones revealed patterns that would finally unlock Monte Sierpe's ancient purpose after 90 years.

Shreesha Sharma, Wikimedia Commons

Shreesha Sharma, Wikimedia Commons

The Breakthrough Study

Dr. Jacob Bongers from the University of Sydney assembled an international research team, which included Charles Stanish from the University of South Florida. On November 10, 2025, they published their groundbreaking findings in the prestigious archaeological journal Antiquity, and the mystery was solved.

Drones Reveal Hidden Patterns

Comprehensive drone mapping exposed mathematical precision in the hole arrangements. One section contained exactly 9 consecutive rows with 8 holes each, totaling 72. Another featured 12 rows alternating between 7 and 8 holes. This was a deliberate calculation.

Microbotanical Analysis

Scientists extracted sediment samples from multiple holes and analyzed them under microscopes. They discovered ancient pollen grains from maize, the Andean staple crop, plus bulrush and willow reeds used for weaving baskets. Humans deposited this pollen intentionally.

Radiocarbon Dating Results

Charcoal fragments recovered from the holes were radiocarbon-dated, indicating construction between 1320 and 1405 CE. This timeframe falls squarely within the Late Intermediate Period, before the Inca conquest. The Chincha Kingdom built Monte Sierpe first. The Incas inherited it decades later.

The Chincha Kingdom (1000–1400 CE)

Long before Spanish arrival, the Chincha Kingdom dominated Peru's southern coast from 1000 to 1400 CE. This powerful civilization governed over 100,000 people across a significant coastal territory. They built cities while developing trade networks and created innovations that would astonish future archaeologists.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Chincha Society And Economy

Chincha society was organized into specialized groups working cooperatively. Seafaring merchants worked their way through Pacific currents in oceangoing vessels. Llama caravans trekked mountain passes connecting the coast to the highlands. Their traders exchanged corn, cotton, fish, textiles, and coca leaves across regional networks.

How The System Worked

The holes created a visual public marketplace regulating fair exchange. Specific hole quantities with maize equaled equivalent amounts of cotton or coca. Traders could see availability at a glance. Different section sizes likely represented different communities participating in this regulated barter economy.

Karthik jeyaraman, Wikimedia Commons

Karthik jeyaraman, Wikimedia Commons

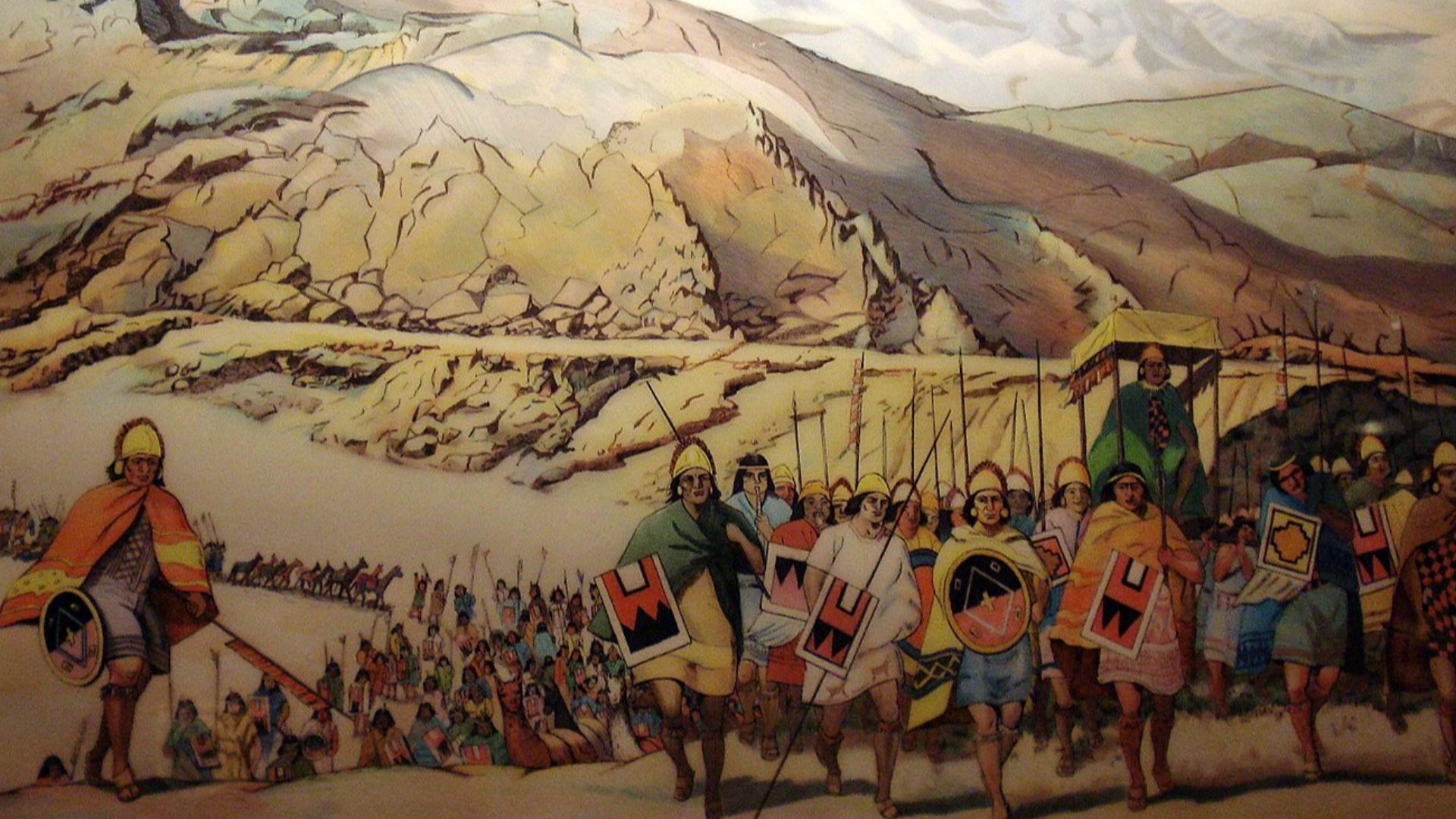

The Inca Conquest (1400–1470 CE)

Around 1400–1470 CE, Inca armies marched from their highland capital Cusco to absorb the Chincha Kingdom into their expanding empire. The Incas recognized Monte Sierpe's strategic position along pre-existing trade routes and decided to transform its original purpose.

Miguel Vera León from Santiago, Chile, Wikimedia Commons

Miguel Vera León from Santiago, Chile, Wikimedia Commons

Inca Empire's Administrative System

The Incas built history's largest pre-Columbian empire entirely without written language. They invented khipus—intricate knotted cords recording numerical data through knot types, positions, and colors. These devices tracked census data and resources across thousands of miles.

The Khipu Connection

Archaeologists had previously recovered a khipu with 80 cord groups from the Pisco Valley. When researchers compared drone maps to this khipu's structure, they noticed striking similarities. Monte Sierpe's hole patterns mirrored khipu counting methods and formed a "landscape khipu" carved into the earth.

gaspar abrilot from Santiago, Chile, Wikimedia Commons

gaspar abrilot from Santiago, Chile, Wikimedia Commons

Inca Tribute System (1470–1532 CE)

After conquering the Chincha, the Incas transformed the marketplace into a state-controlled tribute collection center. Each section's varying hole counts represented different communities' tax obligations. This became the empire's physical ledger, tracking resources and labor contributions without paper.

Spanish Colonial Period Evidence (1532–1825 CE)

Sediment analysis revealed citrus pollen inside the holes. Since Spanish colonizers introduced citrus to South America after 1532, this proves that the site remained active for centuries. Eventually, Spanish administrators abandoned it, and their written records replaced Indigenous landscape accounting systems.

Atlas Þə Biologist, Wikimedia Commons

Atlas Þə Biologist, Wikimedia Commons

Current And Future Research

Bongers' team plans test excavations, additional radiocarbon dating, and more sediment analyses. Researchers will study the types and origins of plants found in holes. It includes those with potential medicinal properties. They're studying more local khipus to explore numerical relationships with Monte Sierpe's design.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Headquarters, Wikimedia Commons

Current And Future Research (Cont.)

Bongers notes these are "hypotheses that can be further tested". Dr. Christian Mader from the University of Bonn calls the marketplace-to-tribute theory "interesting and convincing". This research counters pseudoarchaeology while honoring Indigenous innovation, proving sophisticated economies flourished without currency or writing.