Journey To The Bottom Of The World

On July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong stepped out onto the surface of the Moon. In that moment, NASA and the United States accomplished one of the greatest feats of ingenuity in human history. Not only did they make it to the Moon, but they returned the men who traveled there safely back to earth.

Discussions of the Moon Landings inevitably bring up a comparison. We’ve gone that far up—how far can we go down?

For a long time, there were fewer dives to the depths of the ocean than there were flights to the moon. That’s because the very bottom of the ocean is, in many ways, an even more hostile place than outer space.

But despite the challenges, humans have indeed ventured to the very bottom. In fact, the legendary bathyscaphe Trieste made it there a full nine years before Apollo 11 took flight, and the harrowing dive undertook by Jacques Piccard (the son of the craft’s inventor) and Don Walsh (a US Navy Lieutenant) left us with an incredible story to tell.

Into The Unknown

In 1960, in the bathyscaphe Trieste, Piccard and Walsh traveled to the floor of the Challenger Deep, a precipitous chasm at the bottom of the Mariana Trench. Located in the Pacific Ocean somewhat near Guam, this crescent-shaped depression is formed by the Pacific Plate being forced down into the Earth’s mantel by the encroaching Mariana plate.

It's one of the deepest places in the ocean, but it gets even deeper.

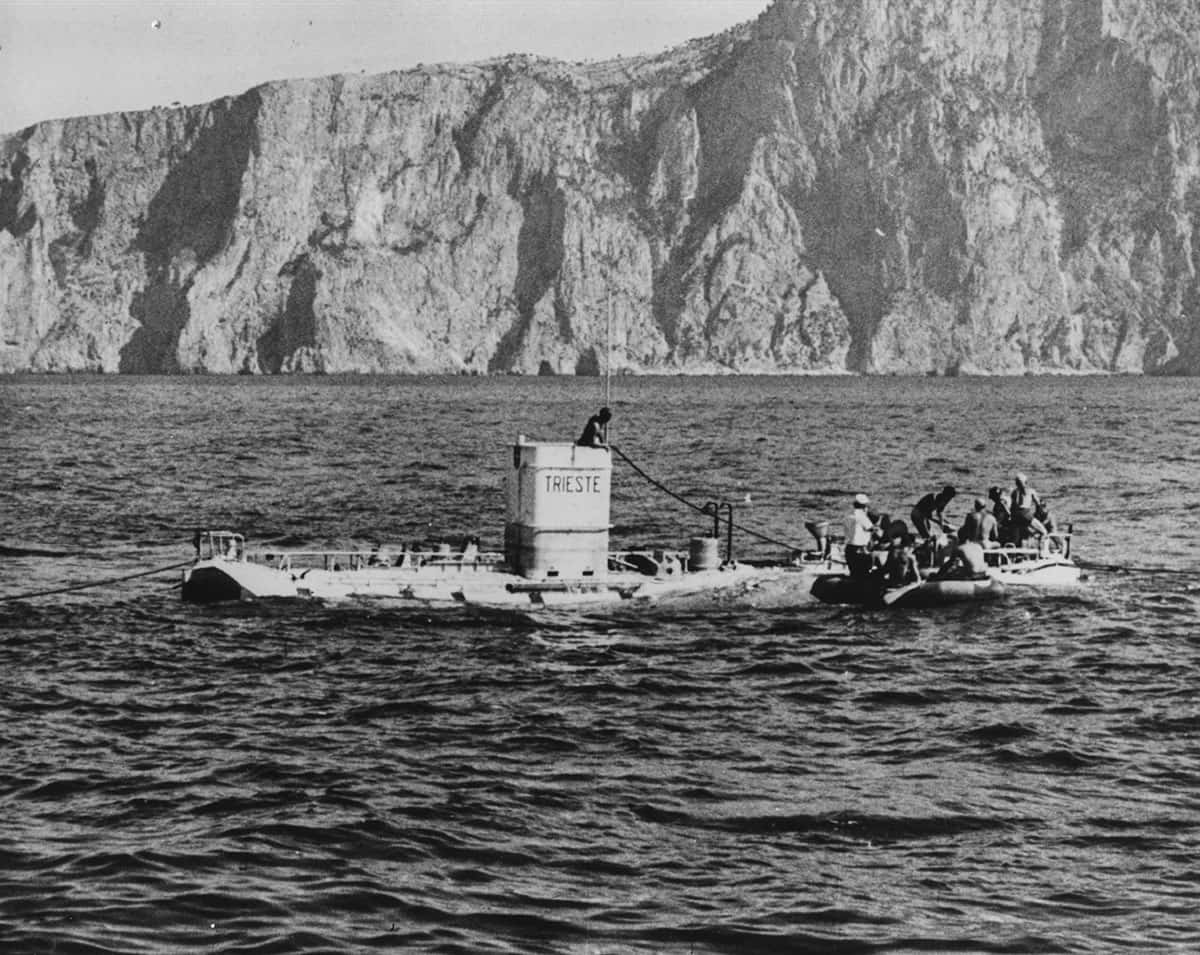

Getty Images Physicist Auguste Piccard and his son Jacques Piccard are part of a crew boarding a rowing boat after surfacing in the bathysphere 'Trieste' following a world record dive off the coast of Ponza, August 21st 1953.

Getty Images Physicist Auguste Piccard and his son Jacques Piccard are part of a crew boarding a rowing boat after surfacing in the bathysphere 'Trieste' following a world record dive off the coast of Ponza, August 21st 1953.

The Deep

The Mariana Trench is around 1,500 miles long, but most people only really care about a small section of it. A slot-shaped canyon about seven miles long and one mile wide. The Challenger Deep. This is where the floor of the Trench drops away and we find the very deepest part of the ocean. Though estimates vary, our best current guess gives it a depth of 35,755 to 35,853 feet.

That means that if Mount Everest were placed at the bottom of the Challenger Deep, its summit would still be over a mile beneath the surface. This is where the bathyscaphe Trieste ventured in 1960.

Don't Call It A Submarine

Most people assume that the Trieste was a submarine, but they’d be wrong. No submarine could ever make it to the Challenger Deep. It would be crushed long before making it that far down. The Trieste is what’s known as a bathyscaphe, a vessel designed exclusively for withstanding the immense pressure at the very bottom of the ocean.

The bathyscaphe was invented by a Swiss scientist named Auguste Piccard, who was an expert in buoyancy. He actually cut his teeth designing completely contrary vehicles: Hot air balloons. Before the bathyscaphe Trieste, Piccard actually set the record for the highest-ever balloon flight.

But after going higher than anyone ever had, he evidently wanted a change of scenery, and he set his sights on the deep.

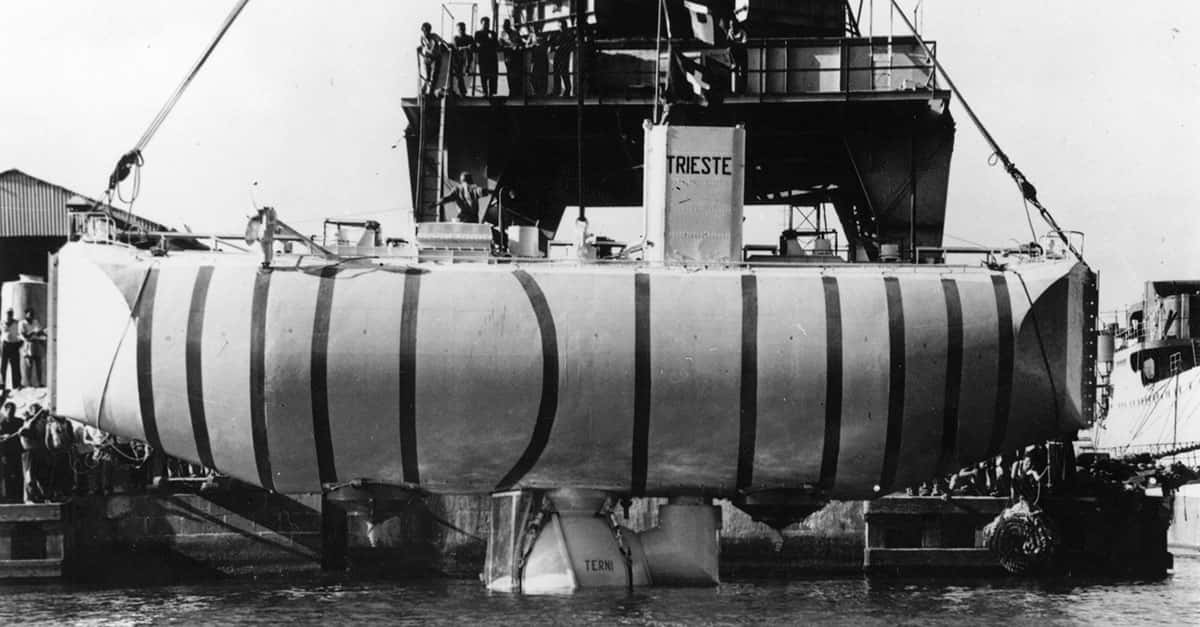

Naval History and Heritage Command

Naval History and Heritage Command

Gas Power

A bathyscaphe may look similar to a submarine, but it’s extremely different on the inside. The main distinction? It’s filled with gasoline.

It may seem like an odd choice, but the fact that gasoline is both lighter than water and effectively incompressible makes it perfect for the job. The former means it will float, and the latter means that it won’t be crushed under the weight of the ocean.

This also ensures that a bathyscaphe can dive freely, and doesn't need to be suspended from a cable at the surface—handy when you're going down over 30,000 feet.

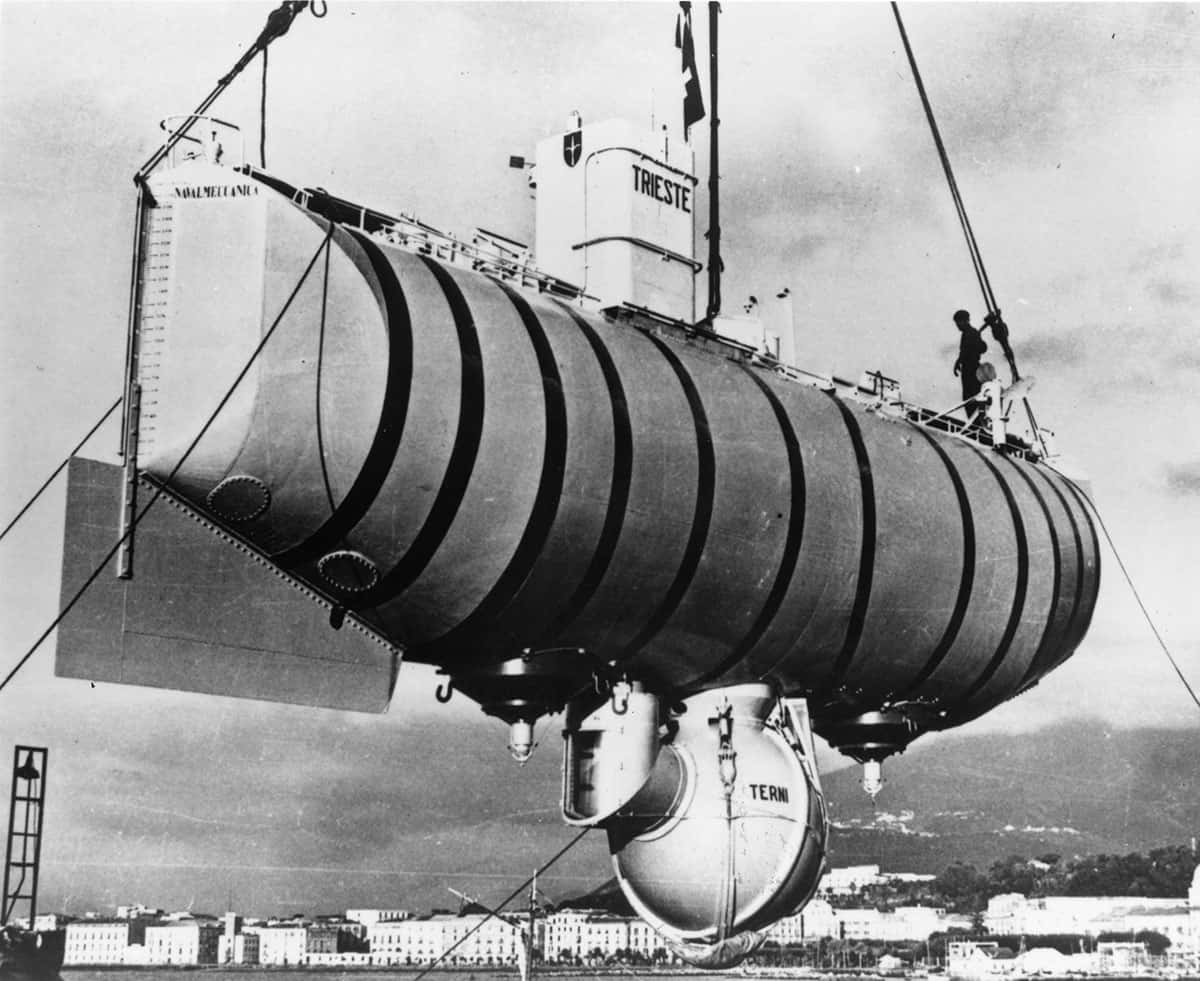

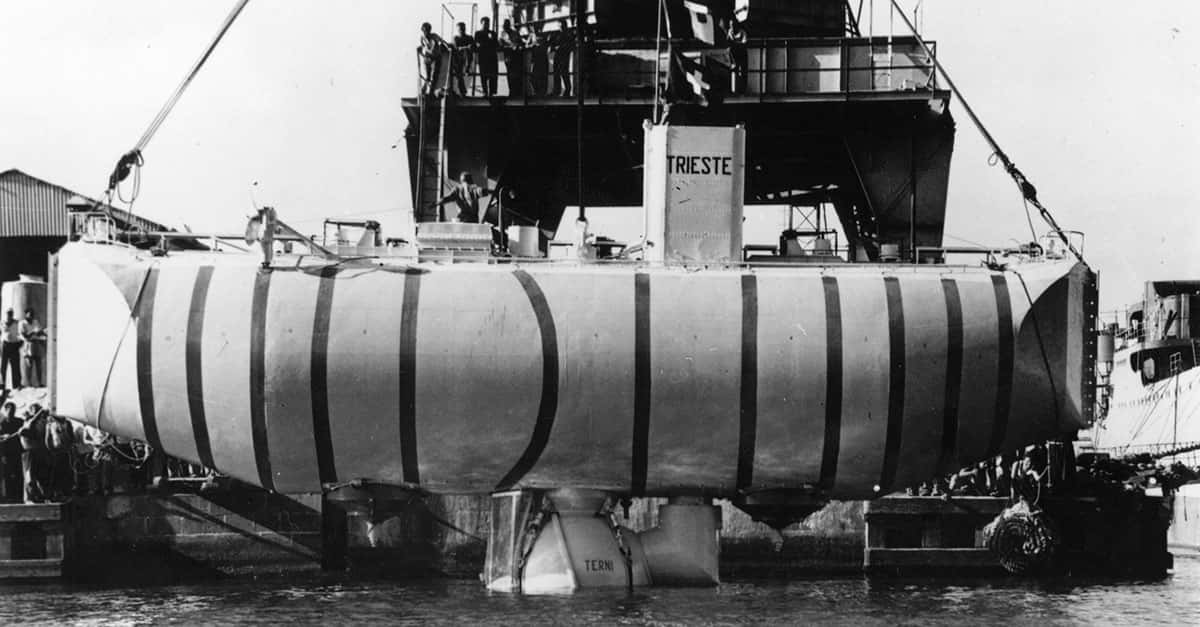

Getty Images The bathyscaphe 'Trieste' submersible research craft designed by Swiss physicist Auguste Piccard and his son Jacques.

Getty Images The bathyscaphe 'Trieste' submersible research craft designed by Swiss physicist Auguste Piccard and his son Jacques.

Trieste Me

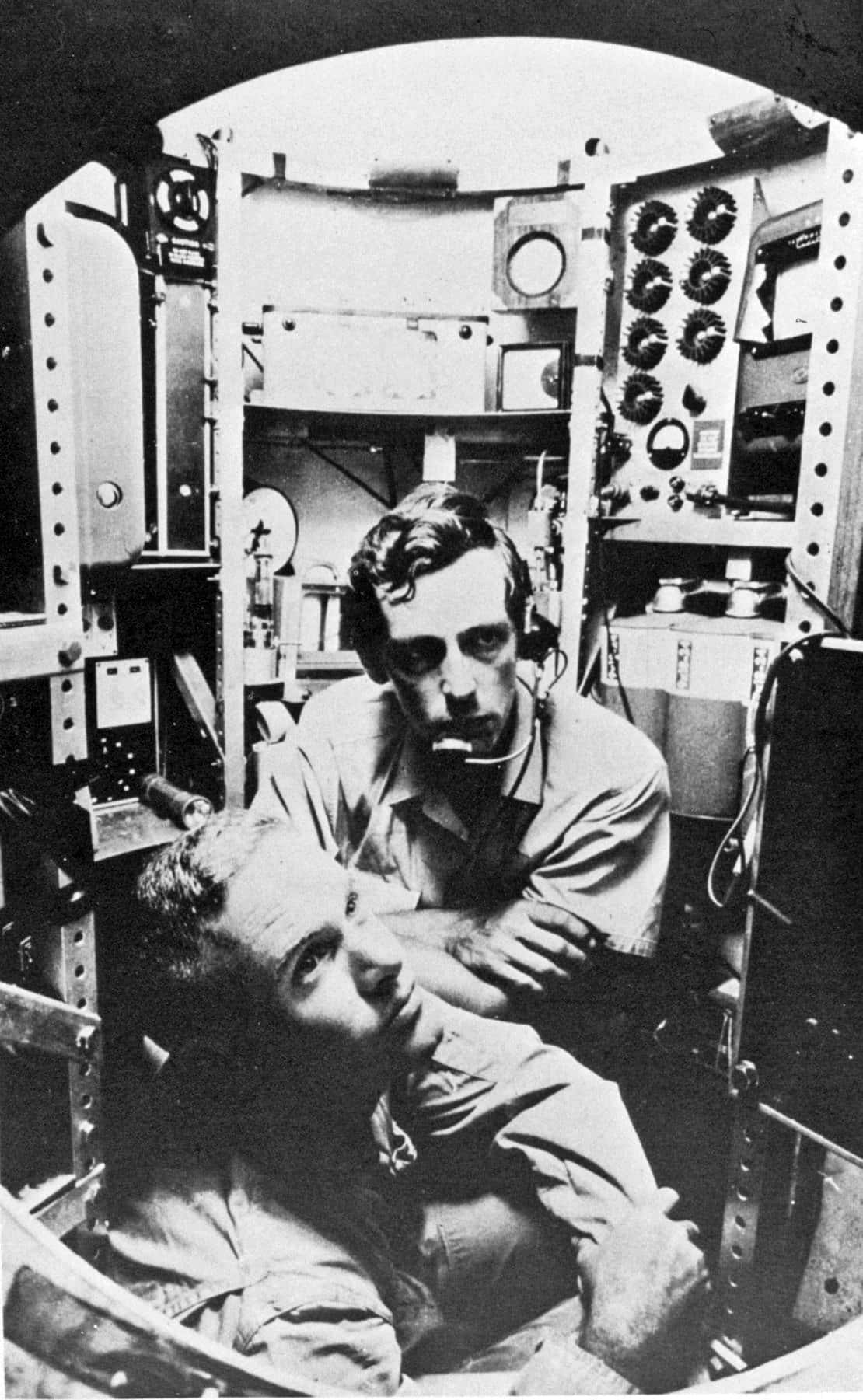

The vast majority of the Trieste's hull was basically a big bucket of gasoline. Underneath, however, there was a small, spherical compartment, about seven feet in diameter. This was where Piccard and Walsh sat. Unlike the rest of the vessel, the cockpit had to be ridiculously overbuilt, so that the crew—and the air they needed to breathe—could sit inside without being crushed under the weight of the ocean.

The Trieste was remarkably large for what seems like a straightforward task. Its 50-foot-long hull was filled with 22,000 gallons of gasoline. It carried 20,000 pounds of iron shot as ballast, and the metal walls of the cramped sphere that held Piccard and Walsh were five inches thick.

They could peek out of a tiny window made out of a cone of plexiglass—the only transparent material available at the time that could possibly withstand the pressure.

Getty Images 5th August 1953: Professor Auguste Piccard (1884 - 1962 ) launches his bathyscaphe'Trieste' at Castellamare di Stabia, Italy.

Getty Images 5th August 1953: Professor Auguste Piccard (1884 - 1962 ) launches his bathyscaphe'Trieste' at Castellamare di Stabia, Italy.

The Dive

On January 23, 1960, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh began their descent to the deepest part of the world. Before the Moon Landings, space agencies had sent many unmanned expeditions first, to make sure it was possible. Piccard and Walsh didn’t have that luxury. The Trieste was the first expedition to the Challenger Deep of any kind.

It took them four hours and 47 minutes to reach the bottom, but the trip was more eventful than they would have hoped. As they passed 30,000 feet, the entire craft suddenly shook violently: the acrylic viewing window cracked under the pressure.

Things weren't looking good for Walsh and Piccard.

Keep Going

However, after taking a minute to assess the situation, Walsh and Piccard decided to continue on. Thankfully, the cabin did not de-pressurize: as Walsh later put it, “if the cabin’s shell had been breached, we’d have been puddles of red mush.”

A little shaken but undeterred, they kept on going down until their instruments noted a depth of 37,799 feet (that number was later recalculated to be 35,814 feet). In a delightful surprise, their communication system actually worked, even at such an extreme depth, and they were able to make contact with the surface—though it took their messages a full seven seconds to get there.

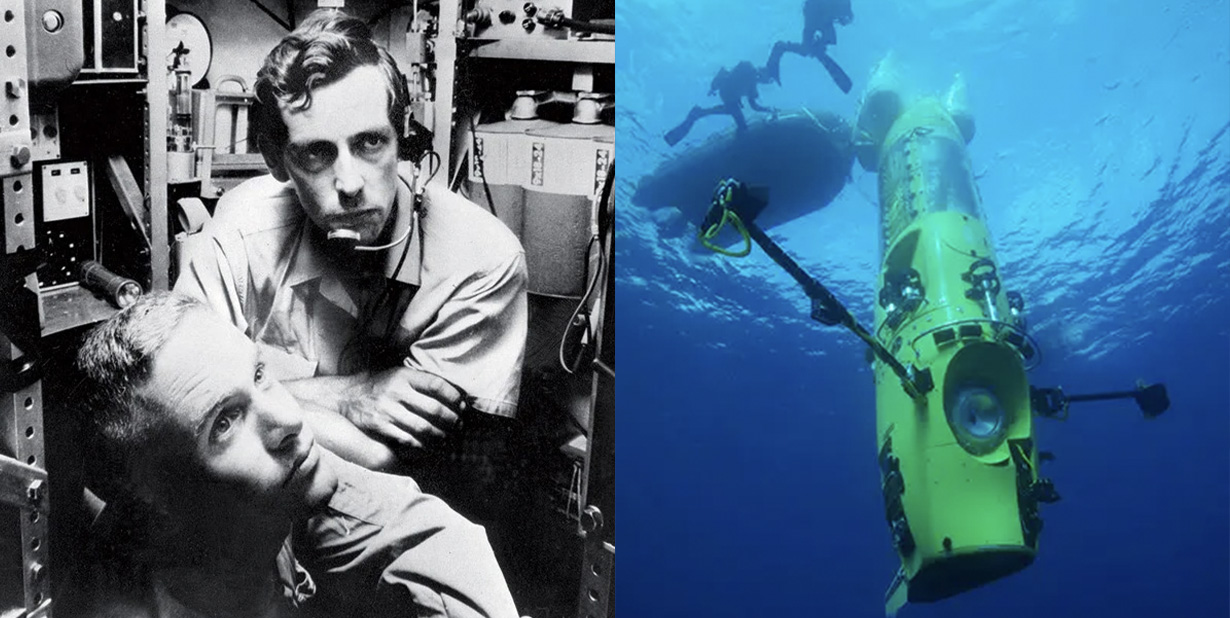

Wikimedia Commons Lieutenant Don Walsh, USN, and Jacques Piccard in the bathyscaphe TRIESTE.

Wikimedia Commons Lieutenant Don Walsh, USN, and Jacques Piccard in the bathyscaphe TRIESTE.

Life Finds A Way

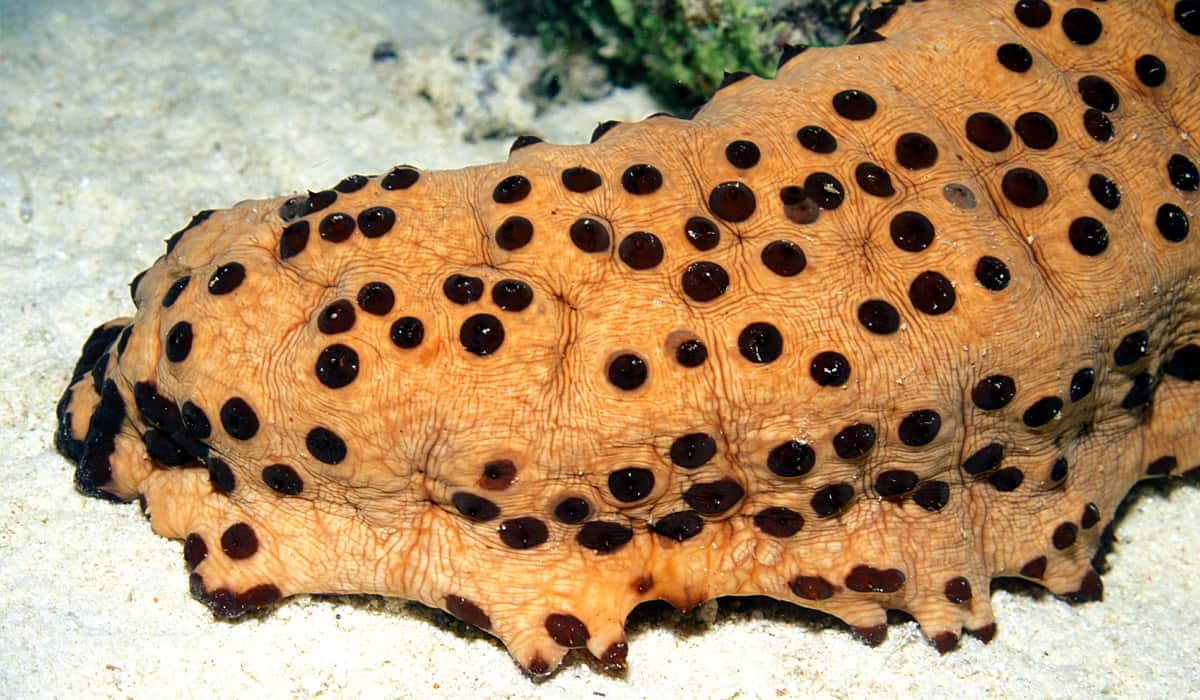

However, the biggest surprise was that Piccard and Walsh saw life among the ooze at the bottom of the Deep. They spent a while gazing at delicate shrimp-like creatures. They even noted seeing multiple flatfish—though, sadly, modern science now believes they mistakenly labeled a sea-cucumber or another kind of invertebrate, since the theoretical maximum depth a fish could survive is around 27,000 feet.

Still, finding any life at all in the Challenger Deep was more remarkable than anyone expected out of the voyage. If there were anywhere on Earth that life could not survive, it would be here—and yet life still managed to gain a foothold. It was a cause for excitement, but Walsh and Piccard could only relish the moment for so long.

The Trieste was sturdy, but it couldn't withstand the Challenger Deep indefinitely. After just 20 minutes—notably shorter than any of the Moon Walks—Piccard and Walsh jettisoned the iron shot and began their ascent.

Following In Their Footsteps

The two men triumphantly broke the surface three hours and 15 minutes later. Auguste Piccard’s design had worked nearly perfectly. The Trieste had braved one of the most hostile places on Earth and come out the other side. The Challenger Deep had been explored.

No one would return until 2012, when Canadian filmmaker James Cameron made his own descent in a craft called the Deepsea Challenger—though Cameron didn’t make it quite as deep as Trieste had in the 60s.

No vessel would manage to make it deeper than Trieste until 2019, when the DSV Limiting Factor expedition performed four dives into the Challenger Deep. The expedition made four dives to the Challenger Deep, the deepest of which made it 50 feet further than the Trieste.

Worlds Apart, The Same Goal

President John F. Kennedy said that the US set the moon as a goal not because it was easy, but because it was hard. “Because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept.” The same inspiration drove the Trieste expedition. The US Navy’s aim was “to demonstrate that the United States possesses the capability for manned exploration of the sea down to the deepest part of its floor.”

In both cases, they met those goals. They proved that human ingenuity can take us to the ends of the Earth and beyond. To the most dangerous and inspiring places imaginable. But while the world was on hand to witness the moment that Neil Armstrong set his foot down on the moon, the Trieste reached the bottom of the ocean in obscurity.

Maybe it’s because we all grew up gazing at the moon, but the bottom of the ocean is an abstract. It’s obstructed by miles and miles and dark, foreboding water. But human beings have always wanted to go as far as possible. Whether it’s Everest, the Moon, or the Challenger Deep, we always seem to find a way.

But it takes a special kind of person, whether it was Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin or Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh, to take that first step.

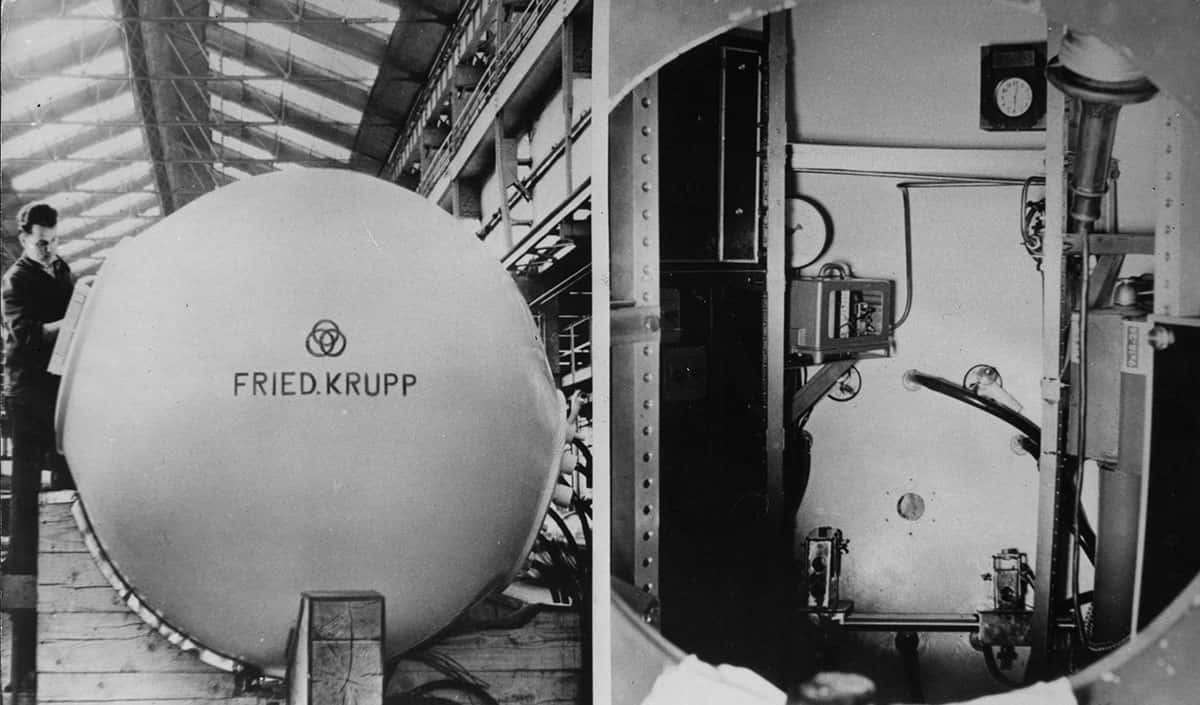

Getty Images 26th January 1960: Jacques Piccard's bathyscaphe Trieste at the Krupp factory in Essen. Built in 1953, by his father Auguste Piccard, Trieste set a world depth record on January 23, 1960.

Getty Images 26th January 1960: Jacques Piccard's bathyscaphe Trieste at the Krupp factory in Essen. Built in 1953, by his father Auguste Piccard, Trieste set a world depth record on January 23, 1960.