The Mysterious Desert Staircase

In Egypt’s desert north of Giza, a narrow staircase descends into solid limestone. It lacks inscriptions and visible chambers at the surface, yet its preserved form invites exploration of the Fourth Dynasty’s building techniques.

Otebig, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Otebig, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

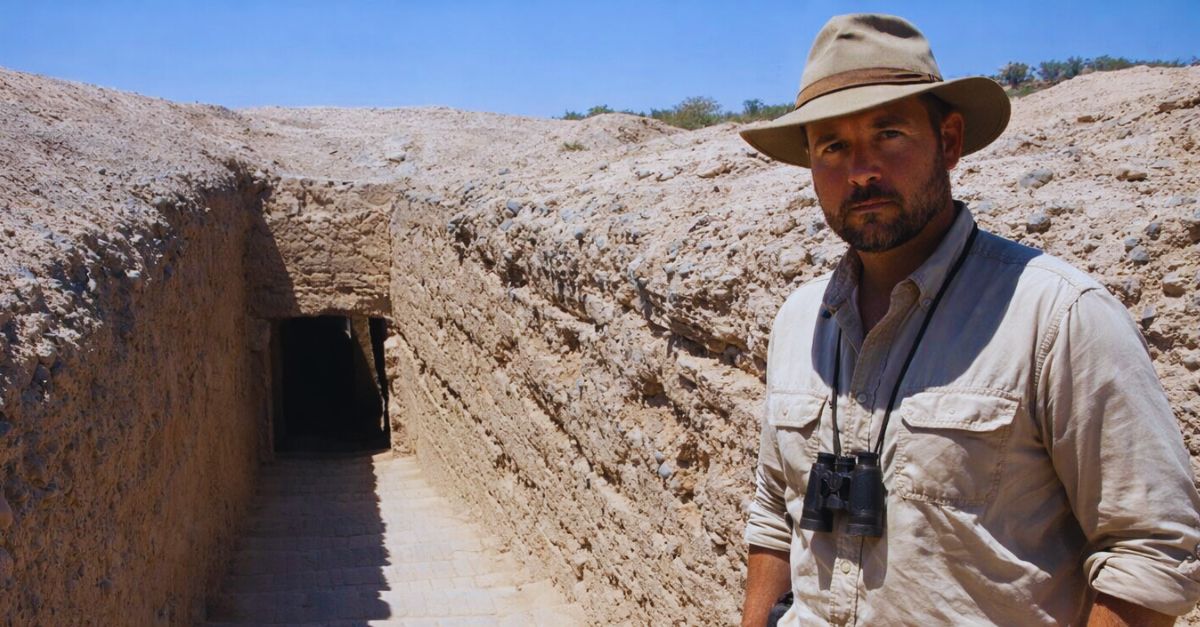

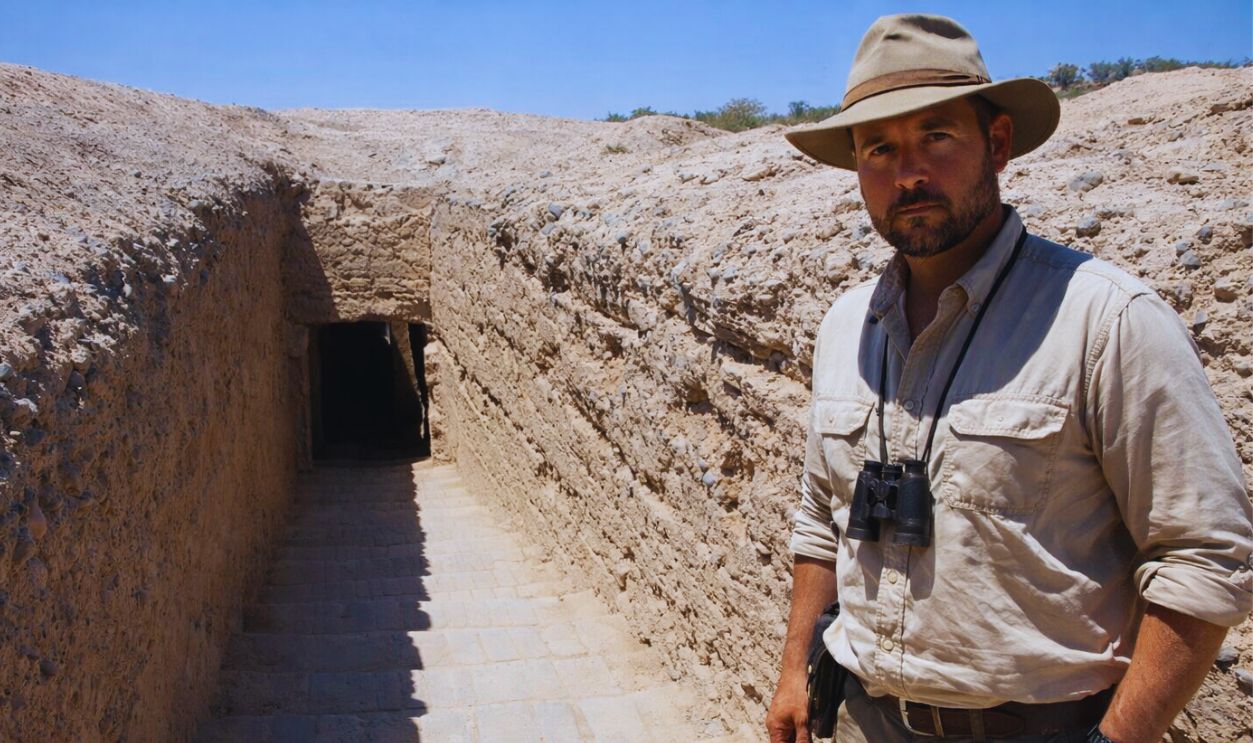

Discovery At Abu Rawash

The Pyramid of Djedefre sits eight kilometers north of Giza at Abu Rawash, Egypt's most northerly pyramid location. French Egyptologist Emile Chassinat excavated the site between 1900 and 1902, uncovering funerary settlements and statue fragments. Among the ruins lay a mysterious 49-meter channel carved into bedrock.

No machine-readable author provided. AhlyMan assumed (based on copyright claims)., Wikimedia Commons

No machine-readable author provided. AhlyMan assumed (based on copyright claims)., Wikimedia Commons

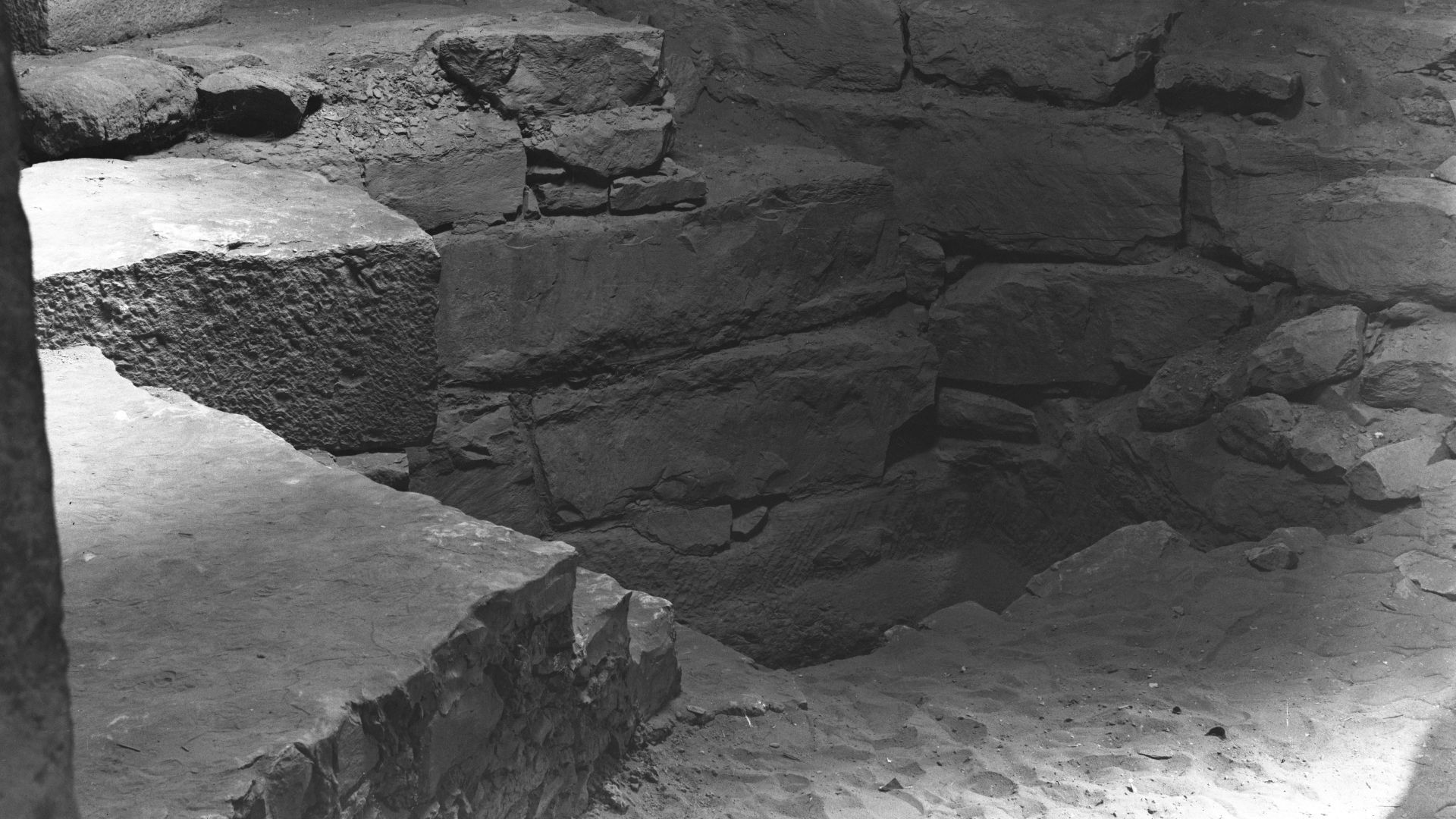

The Staircase That Leads Nowhere

A massive trench descends through limestone bedrock to a 20‑meter (65‑foot)‑deep shaft with a staircase that leads to a T‑shaped burial area containing an antechamber and chamber. For over a century, archaeologists have studied this elaborate descent and debated its innovative design in the context of Fourth Dynasty burial practices.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Who Built The Pyramid

Djedefre was Khufu's son and successor, ruling for just eight years between 2566 and 2558 BCE during Egypt's Fourth Dynasty. He chose Abu Rawash instead of joining his father at Giza. His cartouche, discovered in the burial chamber, confirmed the pyramid belonged to him.

Why The Location Matters

Abu Rawash sits on a high plateau offering sweeping views of the Nile Valley below. The site lies closer to Heliopolis, the ancient center of Ra worship, than Giza does. Proximity to the sun god's cult center likely influenced Djedefre's controversial decision to abandon his father's necropolis.

Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, Wikimedia Commons

Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, Wikimedia Commons

The Roman Well Theory

Some theories, often shared by tour guides, propose that the Romans dug the staircase centuries later as a step well. They occupied Egypt and frequently excavated deep into the limestone bedrock to reach underground water sources.

Why Egyptologists Remain Skeptical

Antoine Gigal, an experienced researcher into ancient Egypt, stated that she had never seen anything like this structure before. The scale, precision, and location align more with Fourth Dynasty techniques than typical Roman wells, as confirmed by ongoing analyses.

The Pit And Ramp Technique

The central excavated hole measures roughly 21 by 9 meters (69 by 30 feet) at the surface. This "pit and ramp" method represented architectural innovation not previously used on such a scale. Burial chambers were constructed within the pit before backfilling and building the pyramid superstructure overtop.

Viktor Lazić, Wikimedia Commons

Viktor Lazić, Wikimedia Commons

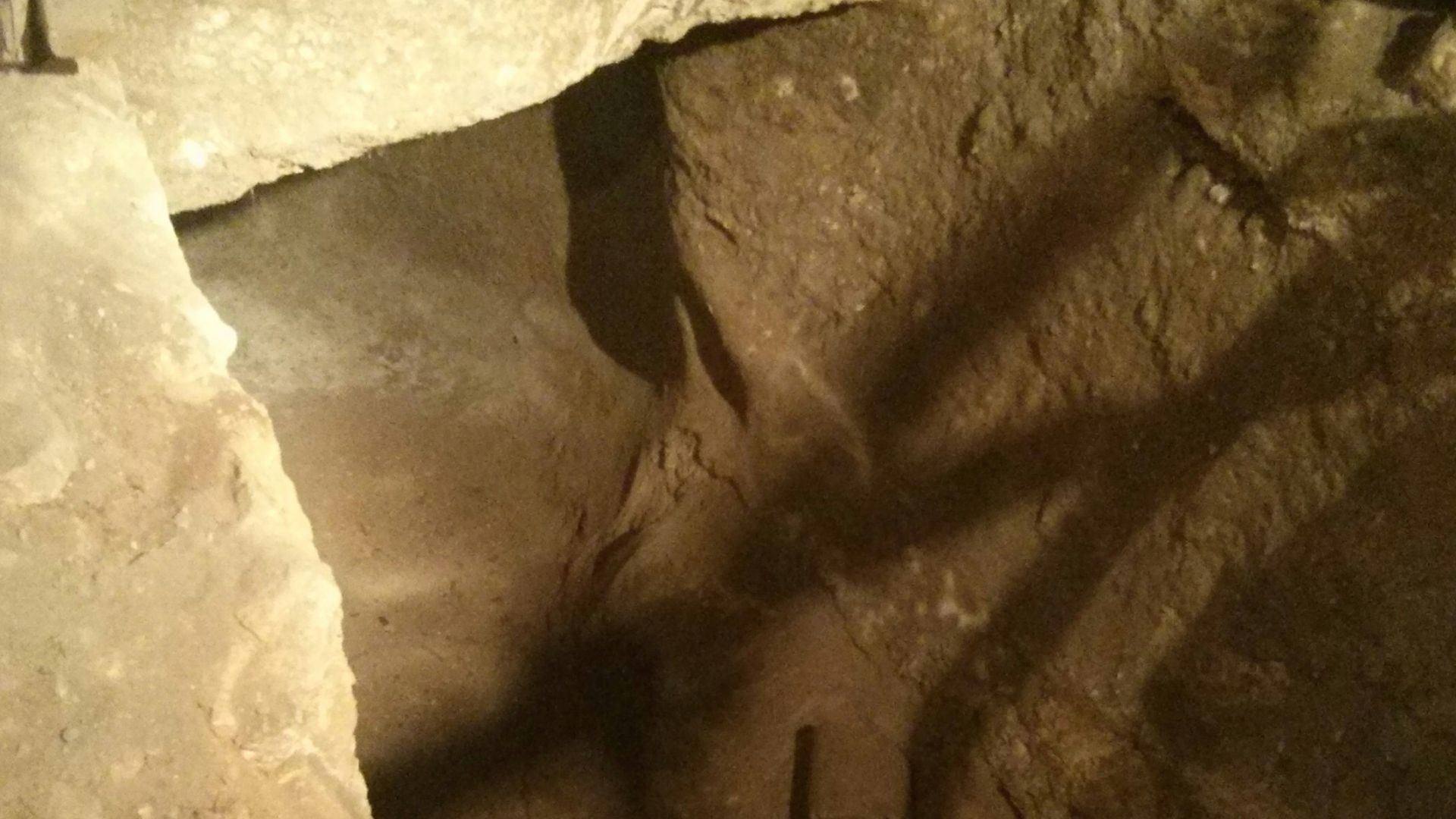

Chambers Built Below Ground

Unlike other pyramids where chambers sit inside the structure, Djedefre's burial rooms were carved beneath the pyramidal base. This unusual design choice has no clear explanation from surviving records. The technique echoes Third Dynasty methods seen at Djoser's Step Pyramid centuries earlier.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

The Descending Corridor

The sloping passage stretches 49 meters (161 feet) from the pyramid's north side down to the deep shaft. This approach followed the customary pyramid design, where northern entrances led to burial areas. A foundation deposit containing a copper axe blade was buried in the descending corridor during construction.

What The Shaft Dimensions Reveal

The central excavated hole measures roughly 23 by 10 meters (75 by 33 feet) at the surface. Depth reaches 20 meters (65 feet) straight down through solid limestone bedrock. The precision required to carve such dimensions without modern tools demonstrates remarkable engineering skill, regardless of who created it.

Siebenberghouse, Wikimedia Commons

Siebenberghouse, Wikimedia Commons

Natural Bedrock As A Foundation

Builders intentionally used a naturally occurring hillock as part of the pyramid's core structure. This technique saved labor while providing a stable foundation for the monument above. The bedrock mound still visible today formed the pyramid's heart before limestone blocks were added around it.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

The Ruined State Today

Only about 12 meters (39 feet) of the structure remains standing after centuries of systematic quarrying. Romans and early Christians treated Abu Rawash as a convenient stone source due to its location near major crossroads. What once rivaled Menkaure's pyramid in size now barely rises above the bedrock platform.

Evidence Of Intentional Completion

Early archaeologists assumed the pyramid was never finished based on its ruined condition. Modern analysis published in 2011 confirmed the structure was substantially developed and likely completed before destruction. Statue fragments, boat pits, and temple remains prove that an active royal cult functioned here.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

The Missing Valley Temple

Most Fourth Dynasty pyramid complexes included valley temples connected by causeways to mortuary temples. Despite extensive excavation, no trace of a valley temple has been discovered at Abu Rawash. Either it was completely obliterated by quarrying, or Djedefre's complex never included one.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Red Quartzite Statue Fragments

Excavators discovered over 120 statue fragments dumped into what was likely a boat pit. Three painted heads carved from red quartzite depicted Djedefre himself, with one possibly representing the earliest known royal sphinx. Romans or Christians likely defaced these statues deliberately centuries after their creation.

The Satellite Pyramids

A small pyramid at the southwest corner may have been a cult pyramid or tomb for one of Djedefre's wives. Another recently discovered pyramid at the southeast corner contains a shaft leading to chambers where a limestone sarcophagus fragment was found. The sarcophagus possibly belonged to Hetepheres II, Djedefre's wife.

Limestone Layers Of The Plateau

The Giza Plateau consists of Middle Eocene-aged limestones from the Mokattam Formation. These same limestone layers extend to Abu Rawash and were used to construct pyramids throughout the region. The bedrock's varying hardness affected how structures weathered over millennia.

Jerome Bon from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

Jerome Bon from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

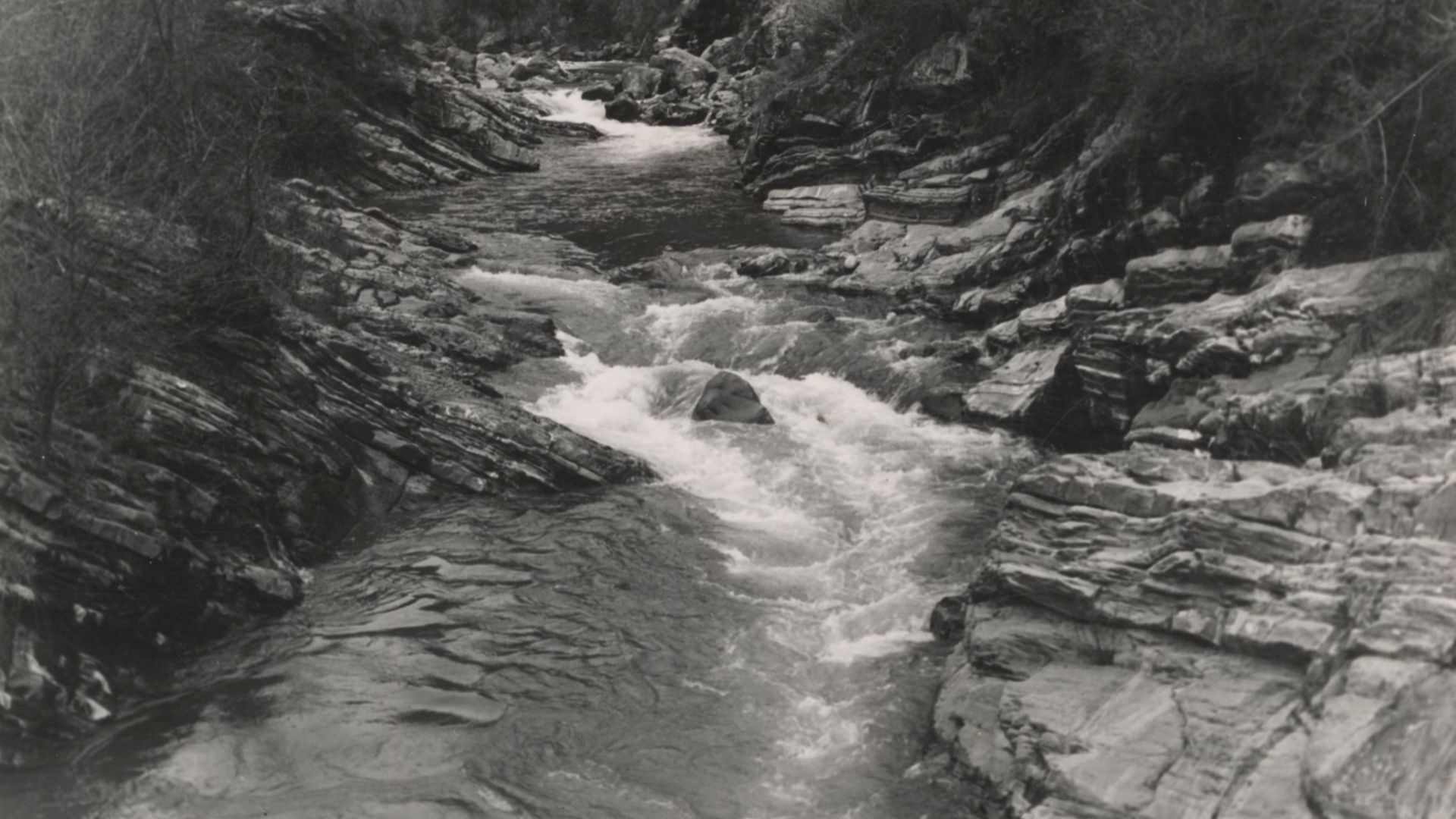

Geological Challenges Of Excavation

Nummulitic limestone in the area consists of layers with dramatically different resistance to erosion. Softer layers disintegrated faster than hard ones, causing uneven degradation visible throughout the site. Ancient workers had to navigate these varying stone qualities when carving the mysterious staircase.

WLU (t) (c) Wikipedia's rules:simple/complex, Wikimedia Commons

WLU (t) (c) Wikipedia's rules:simple/complex, Wikimedia Commons

The Water Table Question

If the Romans carved this as a well, they needed to reach the water table below. Modern groundwater studies show rising water levels on the plateau threaten conservation efforts. Whether ancient water tables sat at the 20-meter (65-foot) depth where the shaft terminates remains unknown.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Satellite Imagery Evidence

Modern researchers used satellite imagery to locate and analyze the staircase from overhead perspectives. Digital mapping revealed the precise alignment with other pyramid structures at the site. These aerial views helped distinguish Roman-era modifications from original Fourth Dynasty construction.

Expedition 20 Crew, NASA, Wikimedia Commons

Expedition 20 Crew, NASA, Wikimedia Commons

Alternative Theories About Purpose

Some scholars propose the shaft held symbolic significance for solar worship or afterlife journeys, while others view it as an innovative but transitional burial access design. The lack of connecting chambers or passages makes determining original intent nearly impossible.

Aidan McRae Thomson, Wikimedia Commons

Aidan McRae Thomson, Wikimedia Commons

Fourth Dynasty Mastabas Nearby

Approximately 50 mastaba tombs surround Djedefre's pyramid at some distance from the main structure. Unlike Giza's organized necropolis, these tombs were built haphazardly without apparent advance planning. Most feature external walls of large limestone blocks layered around bedrock cores.

Giovanni Marro, Wikimedia Commons

Giovanni Marro, Wikimedia Commons

The Experimental Nature Of The Era

Fourth Dynasty builders constantly experimented with pyramid design and construction techniques. Djedefre's complex represents a transitional phase between step pyramids and the smooth-sided pyramids that defined Egypt's Old Kingdom. The mysterious staircase may simply be an abandoned architectural experiment.

EgorovaSvetlana, Wikimedia Commons

EgorovaSvetlana, Wikimedia Commons

Why Documentation Matters Now

Only careful archaeological recording can preserve knowledge of this structure as erosion and modern development threaten the site. Three-dimensional scanning and photogrammetry document every visible detail before it potentially disappears. Future researchers will rely on these digital records if physical access becomes restricted.

The Enduring Mystery

After more than a century of study, no consensus exists about the staircase's true purpose or origin. Roman well or ancient Egyptian religious structure, the answer lies buried in lost records and eroded stone. What remains certain is that someone invested enormous effort carving this elaborate descent into solid bedrock for reasons we may never fully understand.