Origins Of Human Walking

An ancient fossil from Africa is rewriting the story of human evolution. Evidence of upright walking in this seven-million-year-old ape suggests our early ancestors adapted to new environments far earlier than previously believed.

Discovery Site In Chad's Djurab Desert

The fossil came from Toros-Menalla in the Djurab Desert of northern Chad, one of the most famous sites in human history. Deep sediment layers there preserve evidence spanning millions of years, creating an exceptional record of evolutionary changes. Scientists have made numerous discoveries at this location that help explain how our ancestors developed over time.

Gerhard Holub, Wikimedia Commons

Gerhard Holub, Wikimedia Commons

Toumai: Hope Of Life

On July 19, 2001, a Franco-Chadian team unearthed a nearly complete cranium in Chad's scorching desert. President Idriss Deby nicknamed the fossil "Toumai," meaning "hope of life" in the local Dazaga language—a name given to infants born before the dry season.

Office of the White House (Amanda Lucidon), Wikimedia Commons

Office of the White House (Amanda Lucidon), Wikimedia Commons

Seven-Million-Year-Old Ape Identified

Scientists determined the fossil dates back nearly seven million years to the late Miocene period, which made it far older than most known early human relatives. The age pushes our understanding of human ancestry back by approximately one million years from previous records.

Roger Witter, Wikimedia Commons

Roger Witter, Wikimedia Commons

The Late Miocene Period

The Miocene period lasted from twenty-three to five million years ago and saw major diversification among primates across Africa. Many evolutionary experiments occurred during this era that laid the groundwork for later human development, including the divergence between great apes and hominins.

Species Named Sahelanthropus Tchadensis

Paleontologist Michel Brunet and colleagues officially named the species Sahelanthropus tchadensis in 2002 and published their findings in the journal Nature. "Sahel" refers to the African region near the southern Sahara where the fossils were found, while "tchadensis" honors Chad. Combined, the name means "the Sahel man from Chad".

Ludovic Peron, Wikimedia Commons

Ludovic Peron, Wikimedia Commons

Analysis By The New York University Team

Scott Williams, an associate professor at New York University's Department of Anthropology, led a recent research team that studied leg bone fragments in unprecedented detail. Their 2026 analysis revealed specific structural features that support upright movement, published in the journal Science Advances.

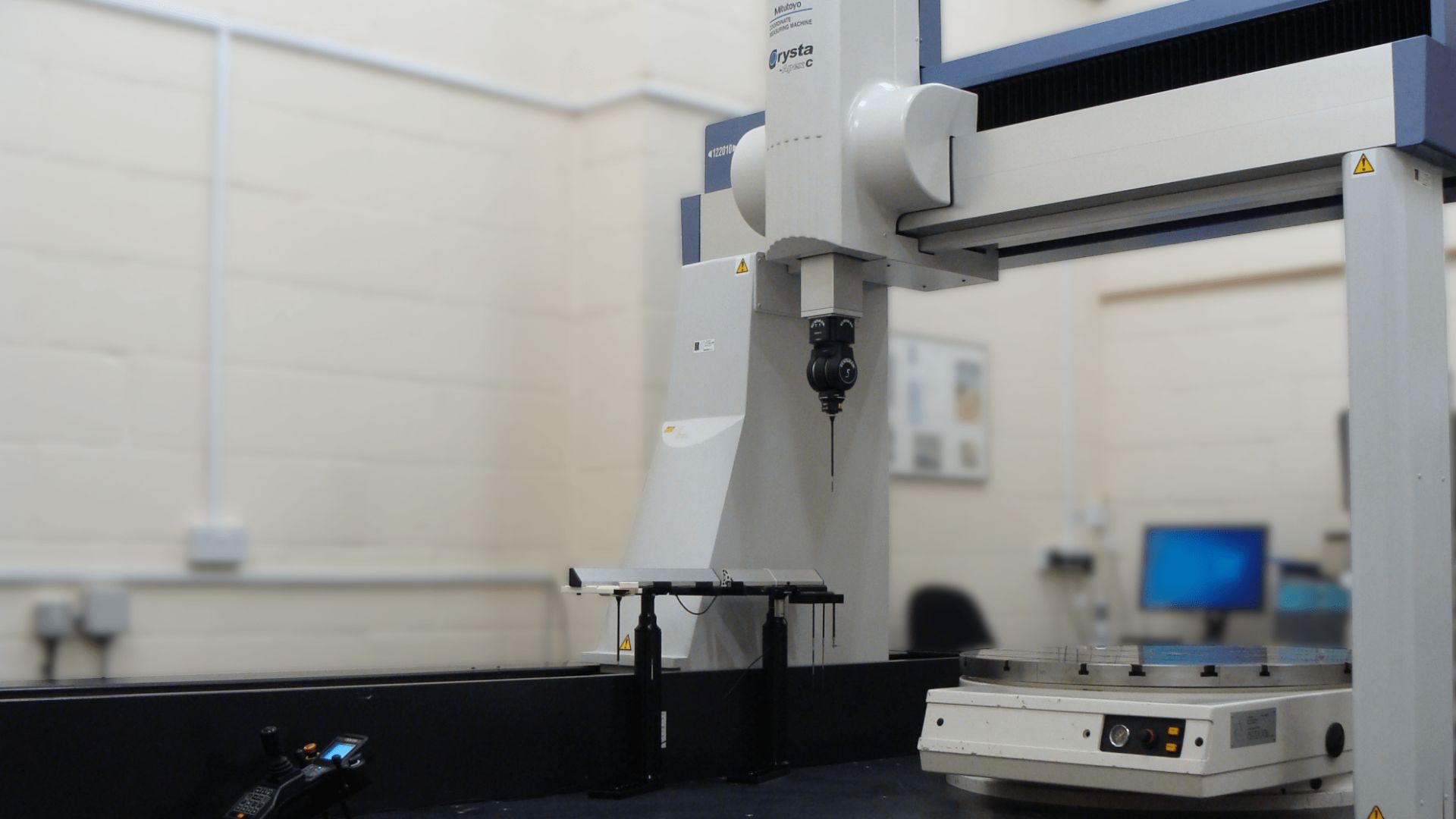

3D Imaging Unlocks Fossil Secrets

Advanced three-dimensional scanning technology allowed scientists to examine internal bone structures without causing damage to the precious fossils. These scans revealed subtle anatomical details beyond what the human eye can detect, including the precise architecture of the femur shaft. The technology made it possible to reconstruct leg anatomy with greater accuracy.

AB Technology (Newark) Ltd., Wikimedia Commons

AB Technology (Newark) Ltd., Wikimedia Commons

Earliest Evidence Of Upright Walking

Bone features linked to upright movement appear clearly in the femur and ulnae fossils associated with Toumai. The evidence shows early support for walking on two legs existed approximately 2.6 million years before Ardipithecus ramidus, a species once held as one of the earliest known walking human relatives.

National Science Foundation, Wikimedia Commons

National Science Foundation, Wikimedia Commons

Femoral Tubercle: The Smoking Gun

The fossil includes a small but significant bump called a femoral tubercle on the thigh bone—a feature appearing only in human relatives, not in apes. Williams and his team identified this structure using 3D geometric morphometrics and tactile examination of the bone surface.

William Daniel Snyder, Wikimedia Commons

William Daniel Snyder, Wikimedia Commons

Iliofemoral Ligament Supports Bipedalism

The iliofemoral ligament is the largest and most powerful ligament in the human body, connecting the pelvis to the femur. It prevents the hip from bending too far backward during upright movement. The presence of its attachment point in Sahelanthropus distinguishes the species from apes that move on all fours.

Paul Hermans, Wikimedia Commons

Paul Hermans, Wikimedia Commons

Femoral Antetorsion Aids Forward Movement

Scientists also confirmed a natural twist in the femur called femoral antetorsion. Such rotation helps orient the legs forward and makes walking more efficient by aligning knees and feet properly. Earlier studies had suggested this feature, but the new 3D analysis definitively confirmed its presence in Sahelanthropus.

Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

Gluteal Muscles For Hip Stability

Three‑dimensional modeling revealed buttock muscles similar to those found in early hominins like Australopithecus. These muscles were designed to stabilize the hips during standing and walking. They keep the pelvis level during a single‑leg stance, a function essential for bipedal locomotion—meaning the ability to move on two legs.

Wolfgang Sauber, Wikimedia Commons

Wolfgang Sauber, Wikimedia Commons

Limb Proportions Reveal Bipedal Adaptations

Apes typically possess long arms and short legs for knuckle-walking, while hominins display the opposite pattern to support bipedalism. Though Sahelanthropus had much shorter legs than modern humans, its limb ratios signal another evolutionary step toward upright walking.

Giles Laurent, Wikimedia Commons

Giles Laurent, Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Lake Chad Environment

Africa experienced major climate shifts seven million years ago as forests gradually gave way to open grasslands across large regions. Sahelanthropus inhabited a diverse landscape near what was then a much larger Lake Chad.

File:An evergreen lake chad shore.jpg: Coolthoom1 removing tilt: Hike395, Wikimedia Commons

File:An evergreen lake chad shore.jpg: Coolthoom1 removing tilt: Hike395, Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Lake Chad Environment (Cont.)

The ancient environment featured forests and rivers alongside wooded savannas. Thousands of vertebrate fossils recovered at the site revealed that the habitat supported giraffes, antelopes, monkeys, crocodiles, and hippopotami in a diverse ecosystem.

File:Waving fisherman on the lakechad.jpg: Coolthoom1 Removed tilt: Hike395, Wikimedia Commons

File:Waving fisherman on the lakechad.jpg: Coolthoom1 Removed tilt: Hike395, Wikimedia Commons

Skull Shows Mixed Ape-Human Features

The Toumai skull presents both human-like and ape-like characteristics. Small canine teeth resemble those of human relatives, while thick brow ridges reflect traits more common in ancient apes. A chimp-sized brain of approximately 320–380 cubic centimeters and a relatively flat face added to the mosaic of features.

Teeth Reveal Dietary Adaptations

Worn molars suggest a diet heavy in plant material, similar to that of chimpanzees, who consume fruit and young leaves with tender shoots. The jaw structure appears built for chewing tough vegetation like roots and fibrous plants.

Afrika Force , Wikimedia Commons

Afrika Force , Wikimedia Commons

Teeth Reveal Dietary Adaptations (Cont.)

Thinner molar enamel compared to later australopiths indicates Sahelanthropus had not yet adapted to harder foods. Open savannas contained grittier vegetation that required different dental structures for successful consumption and digestion over time.

Orrorin And Early Hominin Comparisons

Orrorin tugenensis lived approximately six million years ago in Kenya. It showed some bipedal features but remains controversial in classification among paleoanthropologists. Australopithecus appeared closer to four million years ago with clearer adaptations.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Orrorin And Early Hominin Comparisons (Cont.)

Scientists compare these species to trace gradual shifts in posture and anatomy. Movement patterns changed across different time periods as hominins evolved. This research helps establish connections between various ancient human ancestors and their environments.

Evanmaclean, Wikimedia Commons

Evanmaclean, Wikimedia Commons

Ongoing Scientific Debate Continues

Some experts question the conclusions because fossil material remains limited and the femur shaft lacks its ends—typically the most informative regions. Marine Cazenave from the Max Planck Institute argues that the femoral tubercle appears faint in a damaged area, providing weak evidence.

Rhoda Baer (Photographer), Wikimedia Commons

Rhoda Baer (Photographer), Wikimedia Commons

Arboreal Life Alongside Ground Walking

While adapted for bipedalism, Sahelanthropus likely spent significant time in trees foraging and seeking safety from predators. The ulnae show features consistent with substantial arboreal clambering, which suggests a mixed locomotor repertoire. Such dual adaptation may have characterized early hominins before fully committing to terrestrial life.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Significance Of The Chad Discovery

Finding Toumai in central Africa challenged the prevailing East African Rift theory for hominin origins, showing early human relatives had a wider geographic distribution. Before this discovery, nearly all early hominin fossils came from eastern and southern Africa.

Sani Ahmad Usman, Wikimedia Commons

Sani Ahmad Usman, Wikimedia Commons

Future Research Directions And Questions

Scientists plan further fossil searches across Africa to refine evolutionary connections between Sahelanthropus and later hominins. New discoveries of more complete specimens could clarify relationships between different early species and resolve ongoing debates about locomotion. Additional skeletal material—particularly from the pelvis, ankles, and spine—would provide definitive proof of habitual bipedalism.

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument staff (National Park Service), Wikimedia Commons

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument staff (National Park Service), Wikimedia Commons