Born From The Desert Dust

Thousands of years ago, in the arid sprawl, a culture began to stir. The Ancestral Puebloans, shaped by the Oshara and Picosa traditions, emerged like desert seeds after rain.

Oasis In The Desert

This group was one of the four main cultural groups in the American Southwest, alongside the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Patayan. Together, these cultures formed an Oasisamerica. While the Ancestral Puebloans primarily lived on the Colorado Plateau, their influence stretched across present-day New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado.

Cultural Flourishing Begins

Between 900 and 1150 CE, the Ancestral Puebloans experienced a cultural golden age. Known as the Pueblo II Era, this period saw trade routes expanding across vast distances, and domesticated turkeys became a common sight. Warm, stable climate conditions supported long-term settlement and agricultural success.

Luca Galuzzi (Lucag), Wikimedia Commons

Luca Galuzzi (Lucag), Wikimedia Commons

Stretching From Plains To Plateau

From the Colorado Plateau’s towering mesas to the Rio Grande in the south, their territory sprawled across regions that varied dramatically in climate and resources. The people adapted to these shifts and thrived where others might have faltered in the high-altitude woodlands and the fertile river valleys below.

Andreas F. Borchert, Wikimedia Commons

Andreas F. Borchert, Wikimedia Commons

They Got A Name They Never Chose

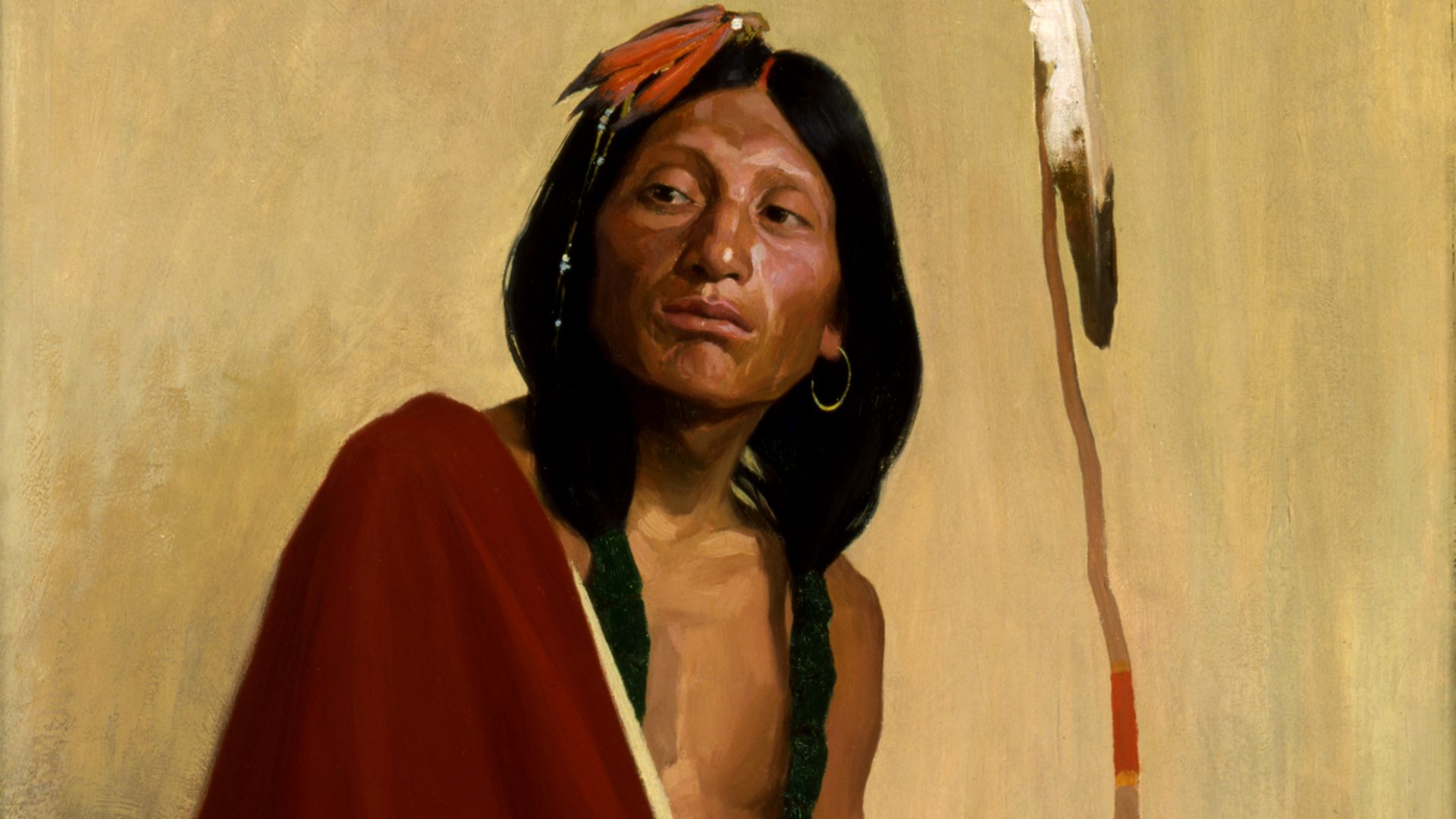

As their presence grew, so did the confusion about who they truly were. Spanish colonizers named them “Pueblo” for their clustered villages, while the Navajo later referred to them as “Anasazi”—a term laden with misunderstanding. Today’s Pueblo folks reject that label, favoring the Hopi term “Hisatsinom,” which means “ancient people”.

E. Irving Couse, Wikimedia Commons

E. Irving Couse, Wikimedia Commons

Villages That Clung To Stone

These people had humble pit houses as well as dizzying cliffside dwellings; their homes evolved in tandem with their stories. These structures, etched into sheer canyon walls, were fortresses, sanctuaries, and engineering marvels. Each stone was fitted with care, and each wall was a tribute to survival.

Andreas F. Borchert, Wikimedia Commons

Andreas F. Borchert, Wikimedia Commons

The Pulse Of The Kiva

At the heart of every village stood the kiva—a circular chamber sunk into the earth. But don’t mistake it for a simple room. These spaces pulsed with spiritual energy, housing rituals, storytelling, and community decisions. Their designs even mirrored the cosmos, and they even…

Followed The Stars

Celestial knowledge was a compass. Architecture danced with the heavens. Solstice alignments, equinox markers, and petroglyphs like the Sun Dagger proved that their skies were understood. Movement, planting, ceremony—everything was tied to the stars. You looked up, and you found direction.

Picture Rocks Sun Dagger by APOD Videos

Picture Rocks Sun Dagger by APOD Videos

Who Did They Believe In?

The religion of the Ancestral Puebloans was deeply spiritual, centered on harmony with nature and the guidance of unseen forces. They believed in divine spirits called kachinas, who influenced rain, crops, climate, and communal well-being. Rituals and masked dances connected the people with these powerful spiritual beings.

Museum Expedition 1904, Museum Collection Fund, Wikimedia Commons

Museum Expedition 1904, Museum Collection Fund, Wikimedia Commons

They Believed Not One But Many Kachinas

To be specific, the Pueblo people believed in over 500 kachinas. Kachinas resided with the tribe for half the year and could appear during sacred ceremonies. When men performed ritual dances wearing kachina masks, the spirit was believed to inhabit the performer, temporarily transforming him into a divine being.

Alan Levine, Wikimedia Commons

Alan Levine, Wikimedia Commons

Cultural Transmission Through Art

Kachinas were represented in carved wooden dolls ornately decorated with feathers, leather, and vibrant colors. Men gifted these dolls to girls, while boys received bows and arrows. These items taught children to recognize specific kachinas and their symbolic regalia, preserving spiritual knowledge and identity across generations within each Pueblo culture.

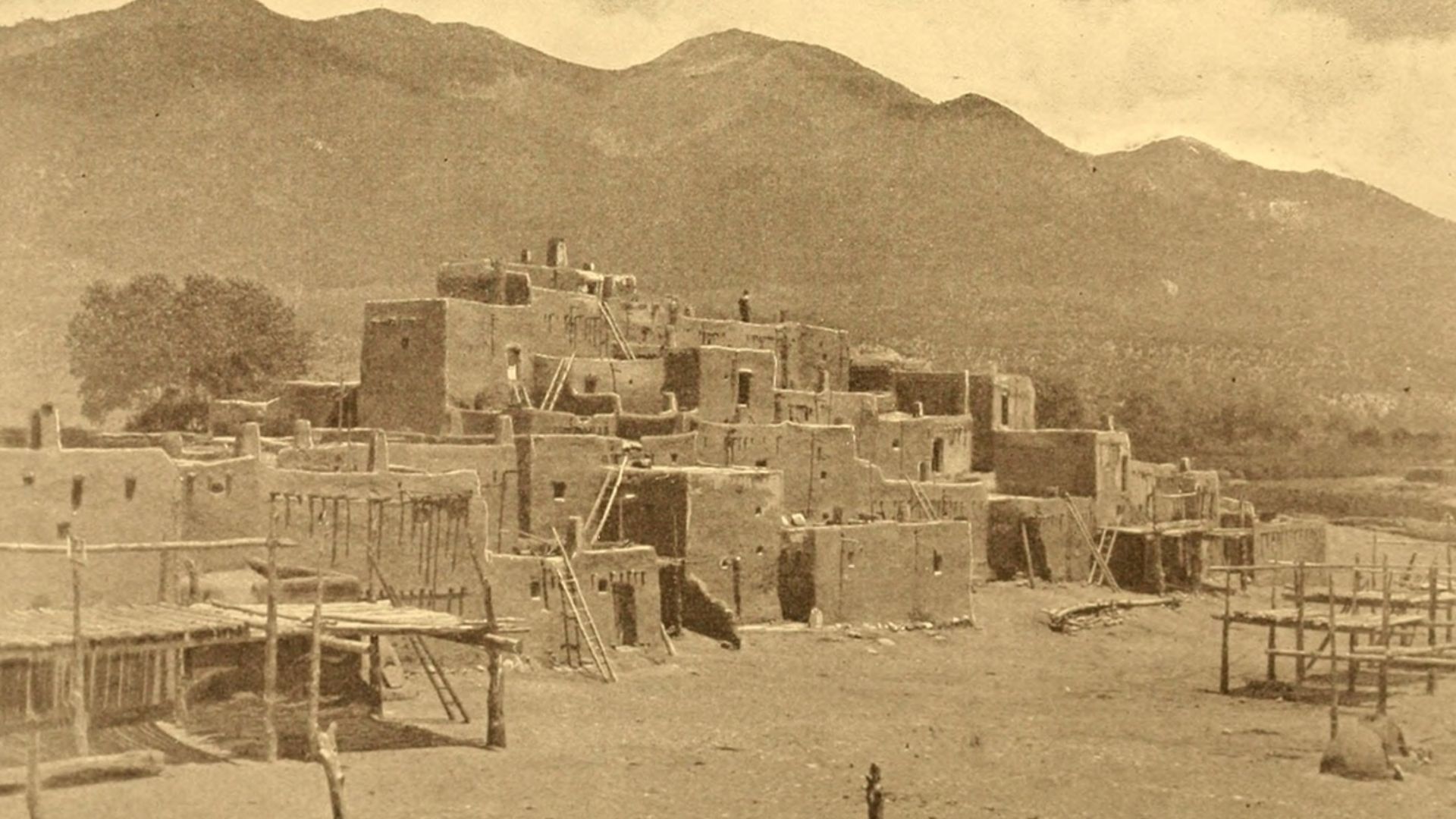

Let’s Talk Architecture

Their structures featured planned community spaces to showcase advanced organization and social cohesion. They used stone, adobe mud, and local materials to build apartment-style complexes that blended naturally with their environment and supported cooperative living across generations.

John Mackenzie Burke, Wikimedia Commons

John Mackenzie Burke, Wikimedia Commons

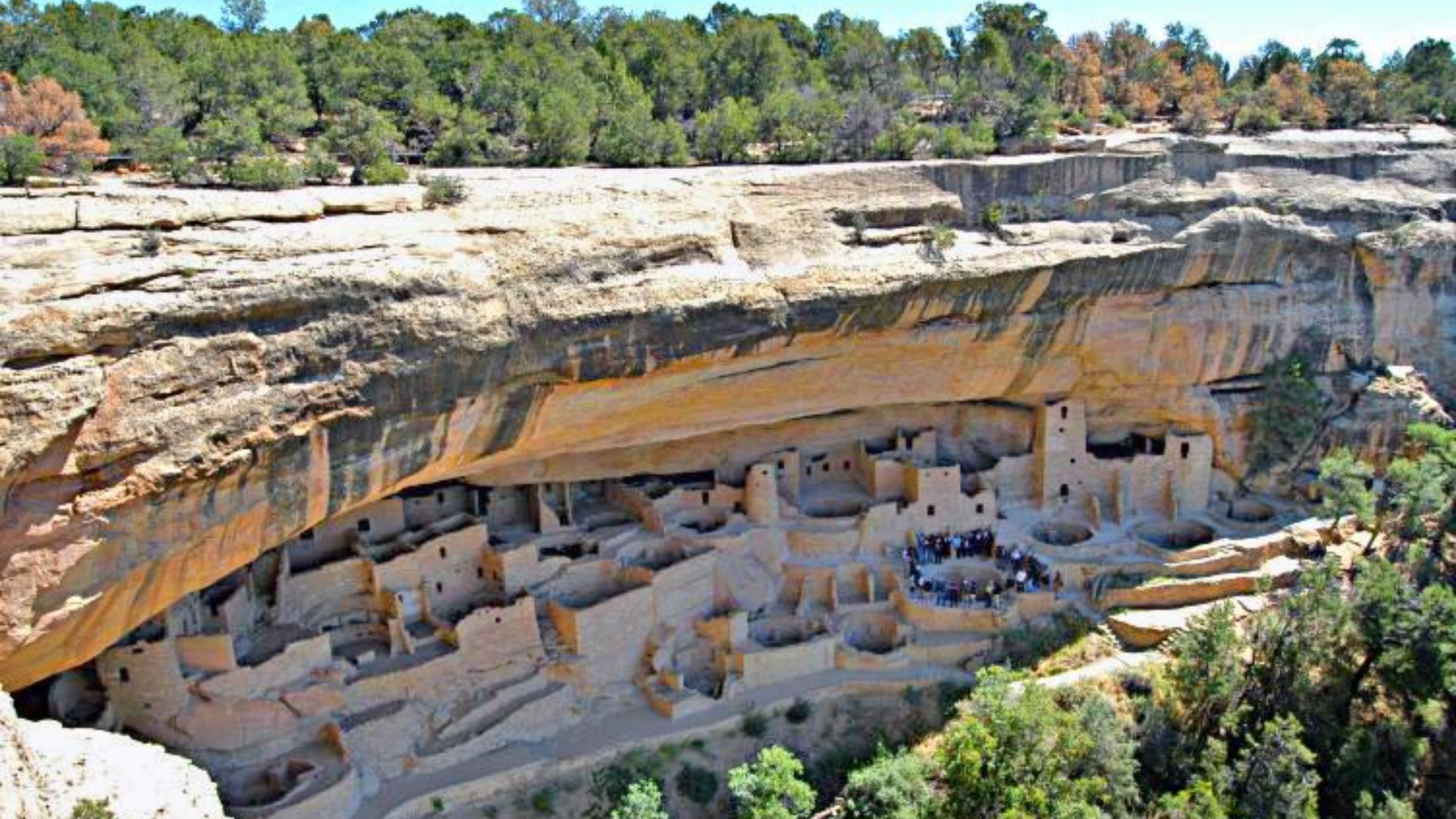

Acclaimed Cultural Sites

Famous Ancestral Pueblo population centers include Chaco Canyon and Bandelier National Monument. Mesa Verde was also part of this group. These sites, located in New Mexico and Colorado, highlight the Pueblo people’s ingenuity.

Influences And Innovation

Although rooted in local traditions, Ancestral Pueblo architecture incorporated design elements from distant regions, including contemporary Mexico. This cultural exchange enriched their building techniques and aesthetic expression. The blend of influences reveals a society that was not isolated but connected.

Scott Catron, Wikimedia Commons

Scott Catron, Wikimedia Commons

Inside A Typical Family Home

Pueblo homes were often massive, with over 100 rooms arranged in long rows and several stories high, designed to house large families. Built from adobe, these multi-story dwellings thrived in dry regions like New Mexico and Arizona. Most pueblos featured underground kivas for gatherings.

Wkgreen (talk) (Uploads), Wikimedia Commons

Wkgreen (talk) (Uploads), Wikimedia Commons

Roads Without Wheels

Beneath those same skies and homes, they carved roads across the plateau. Long and precise, these highways linked far-flung settlements to Chaco Canyon—an ancient superhighway network built for foot travelers. Just imagine walking miles to share a ritual with your loved ones.

Chaco Canyon’s Ceremonial Roads

The Chaco Road system, spanning over 180 miles, connected major great houses, such as Pueblo Bonito, to distant outlier sites and natural features. Built between 1000 and 1125 CE, these wide, engineered roads—complete with ramps and stairways—may have served both economic and ceremonial purposes, linking sacred spots and facilitating regional trade.

BoatingGirl, Wikimedia Commons

BoatingGirl, Wikimedia Commons

Division Of Labor Among Southwestern Tribes

Pueblo cultures saw men weaving textiles while women crafted pottery. Among the Dine (Navajo), men created intricate jewelry, and women specialized in weaving. Apache men focused on crafting tools for hunting and warfare, while Apache women developed skills as basket makers. Each community had distinct, complementary roles rooted in tradition.

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

When Baskets Told The Story

During the Early Basketmaker II era, containers were woven. These baskets carried more than just food, as they also carried tradition and technology. Their artistry bloomed alongside agriculture. Woven vessels overflowed, and the slow transformation from nomad to settler was sealed stitch by stitch. Speaking of agriculture, meet…

National Parks Service, US Department of the Interior, Wikimedia Commons

National Parks Service, US Department of the Interior, Wikimedia Commons

The Three Sisters—Corn, Beans, And Squash

The Pueblo people’s agriculture centered around the “three sisters”: corn, beans, and squash. These crops complemented each other nutritionally and physically—corn provided structure, beans added nitrogen to the soil, and squash shaded the ground. Together, they formed a balanced, sustainable farming system vital for survival in the Southwest.

Garlan Miles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Garlan Miles, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Farming Wasn’t Easy, Though

Farming took place at elevations between 6,000 and 7,000 feet, where the growing season averaged 150 days. Corn needed about 120 days to mature, but fluctuating temperatures—sometimes shifting 40°F in a day—made growing tricky. Sunlight was intense by day, but cool nights slowed growth, requiring adaptive farming techniques.

Bhanupratap59, Wikimedia Commons

Bhanupratap59, Wikimedia Commons

How They Adapted

As rainfall became seasonal, Ancestral Puebloans engineered check dams and terraces to manage runoff and prevent erosion. These interventions reflect proactive agricultural adaptation to demonstrate a working knowledge of hydrology tailored to each site’s microclimate. The systems also supported continued cultivation amid increasing environmental strain and diminishing water tables.

Jeffrey Beall, Wikimedia Commons

Jeffrey Beall, Wikimedia Commons

Engineering Moisture Control

Volcanic pumice acted like a natural sponge; it absorbed and slowly released water into the soil. Farmers used it as mulch and scattered it on plots to prevent total crop loss. Using digging sticks, they planted seeds deeply and widely to promote water retention. Each harvest required careful planning.

Benjamint444, Wikimedia Commons

Benjamint444, Wikimedia Commons

Rise In Internal Conflict

By the 13th century, isolated Ancestral Puebloan villages reportedly began raiding one another for food and supplies. These raids likely emerged from shrinking resources and inter-village competition. This reflected a breakdown in regional cooperation and suggested migration was a necessary measure to escape sustained localized warfare.

Thomas Moran, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Moran, Wikimedia Commons

Pressure From Influx Tribes

Numic-speaking groups—Utes, Paiutes, and Shoshones—migrated onto the Colorado Plateau, and this intensified competition for land. Simultaneously, Athabaskan-speaking Dine moved in from the north. Their arrival may have disrupted established Puebloan systems. It also accelerated migration as original settlers responded to increasing territorial pressure and unpredictable regional dynamics.

Albert Bierstadt, Wikimedia Commons

Albert Bierstadt, Wikimedia Commons

Resource Collapse And Conflict

Advanced sites, such as Chaco Canyon, experienced environmental exhaustion due to overuse. Deforestation and soil depletion led to food scarcity. This scarcity, in turn, may have sparked warfare over remaining resources, and it contributed to a survival-driven dispersal from once-prosperous centers into new, less contested regions.

SkybirdForever, Wikimedia Commons

SkybirdForever, Wikimedia Commons

Cowboy Wash Evidence

A 1997 excavation at Cowboy Wash near Dolores uncovered 24 dismembered skeletons showing signs of violence and cannibalism. The site was abruptly abandoned, but this information supported the theory that extreme social stress or warfare prompted migration. These remains suggest that direct conflict had reached deeply into community life.

Strategic Mesa Relocation

Near Kayenta, Arizona, late-13th-century communities abandoned canyon settlements for high mesas. Archeologist Jonathan Haas interprets this move as a deliberate defense strategy where the people were distancing themselves from vital water sources to protect against attacks. This suggests security outweighed agricultural convenience during periods of increasing social instability and conflict.

Sacred Ridge Massacre

The Sacred Ridge site near Durango revealed evidence of organized violence against a group, possibly ethnic. Archeologists Potter and Chuipka interpret this event as ethnic cleansing, signaling a deeper level of societal fracture. Such intense conflict may have prompted entire populations to flee ancestral homelands.

Multiple Theories, One Result

Whether warfare stemmed from starvation, ritual conflict, nomadic raids, or calculated invasions, all scenarios imply environments too hostile to sustain community stability. Migration appears not as collapse but as a strategic survival effort—an attempt to preserve cultural continuity in safer, more habitable regions.

Cliff Communities And Cultural Continuity

The Ancestral Puebloans relocated into cliff alcoves to construct defensible complexes, such as those found at Mesa Verde. These structures featured shared walls, towers, kivas, and T-shaped doorways. Some archeologists see this architectural continuity as evidence, and others attribute it to broader Pueblo cultural expressions.

Ericksmith2, Wikimedia Commons

Ericksmith2, Wikimedia Commons

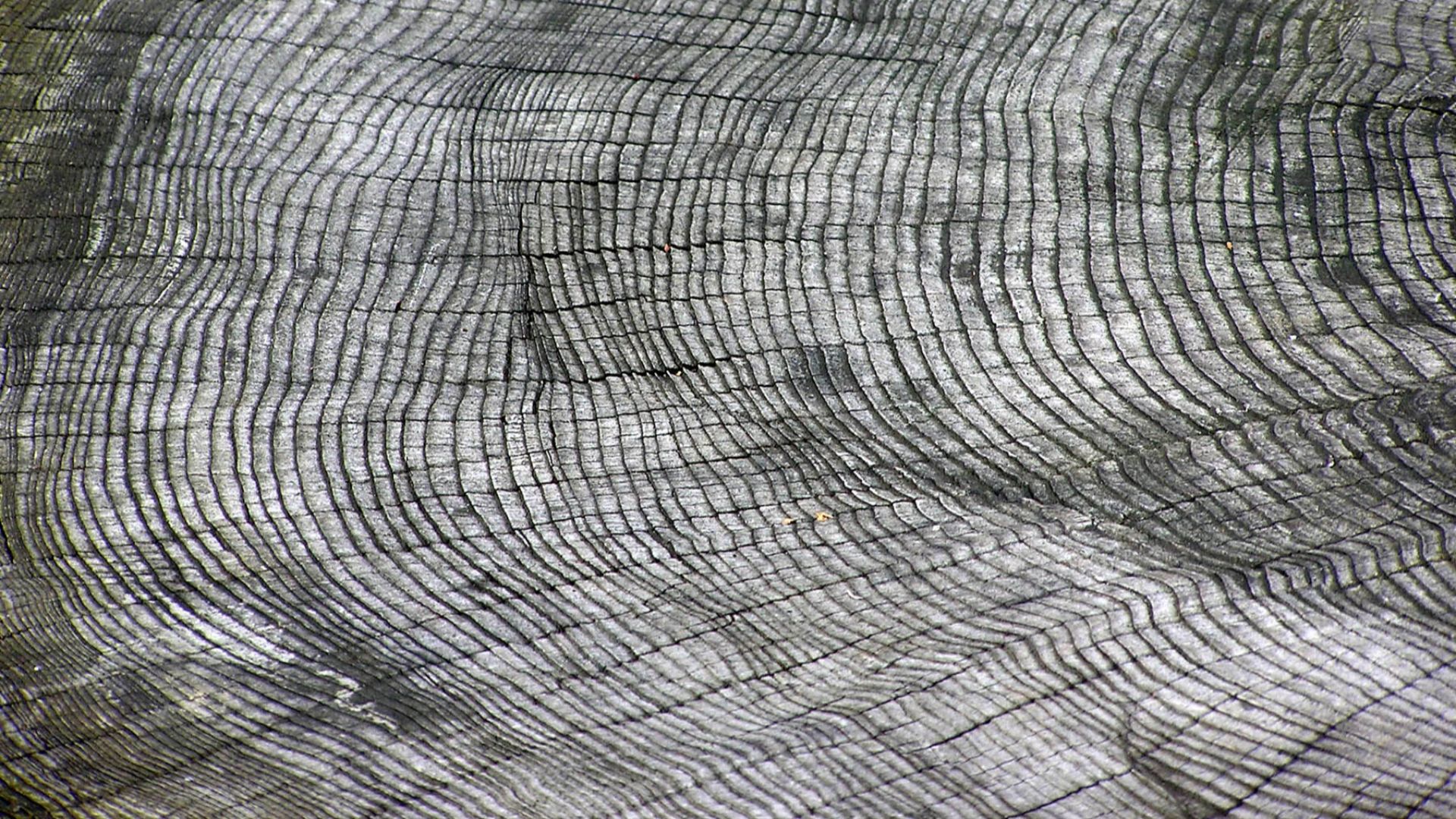

Climatic Disruption Documented

Post-1130, tree-ring data and settlement layers reveal a continent-wide drought phase. Western Mississippi Valley excavations reveal parallel climate patterns characterized by wetter winters and cooler summers. These precise climatic shifts correspond to sudden cultural changes in Chaco Canyon and other ancestral centers.

Arpingstone, Wikimedia Commons

Arpingstone, Wikimedia Commons

Systematic Abandonment Patterns

Sealed doorways, dismantled kivas, and intentionally scorched walls (especially in Chacoan sites) suggest ritual closure rather than hasty desertion. Roof dismantling, which required significant labor, points to organized decommissioning processes. These changes appear in both major ceremonial centers and smaller settlements during the late 13th-century diaspora.

National Park Service (United States), Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service (United States), Wikimedia Commons

Religious Recalibration

Astronomically aligned ceremonial buildings were systematically sealed with rock and mortar. Fire damage inside kivas required the removal of heavy roof beams, indicating deliberate ritual action. These structural acts correspond to oral traditions that describe ancestral attempts to spiritually realign with nature by relinquishing control over cosmic forces.

Karen Blaha from Charlottesville, VA, Wikimedia Commons

Karen Blaha from Charlottesville, VA, Wikimedia Commons

Water Table Decline

Archaeological soil profiles in overfarmed zones confirm declining water tables unrelated to rainfall levels. Settlements were relocated from these zones, not due to drought but rather due to unsustainable land-use cycles. This environmental degradation was met with decisive migration to better-hydrated areas to ensure agricultural continuity.

Brendakochevar, Wikimedia Commons

Brendakochevar, Wikimedia Commons

Migration Routes Identified

Material remains, including pottery typologies and isotopic analyses of timber sourcing, indicate distinct migration routes toward the Arizona and New Mexico river systems. These migrations aligned with more favorable hydrological zones, especially near dependable springs and high-water table basins. This indicated careful environmental scouting rather than random movement.

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Wikimedia Commons

Architectural Continuity Markers

T-shaped doorways and shared kiva designs appear in both ancestral sites and later Pueblo settlements. San Ildefonso oral tradition connects their lineage to Mesa Verde and Bandelier. Archeologist Stephen Lekson interprets these motifs as evidence of elite continuity rather than collapse, suggesting that Chacoan social influence extended beyond its peak.

Rationalobserver, Wikimedia Commons

Rationalobserver, Wikimedia Commons

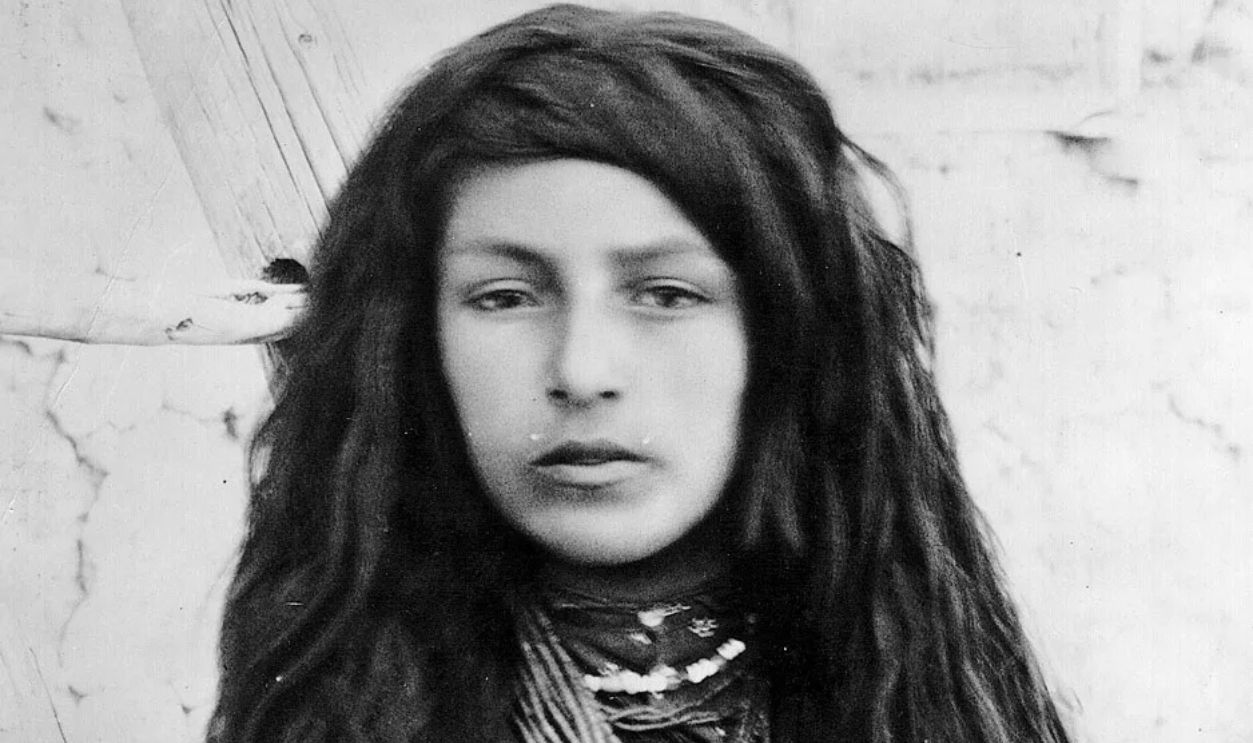

A Disappearance That Wasn’t

Around 1300 CE, the great cities began to empty. Was it drought? Resource collapse? Conflict? Maybe all of it. But here’s the twist—they didn’t vanish. They migrated. The Hopi, Zuni, and other Pueblo people are their living heirs. Their ceremonies, rituals, languages, and oral histories carry echoes of canyon footsteps.

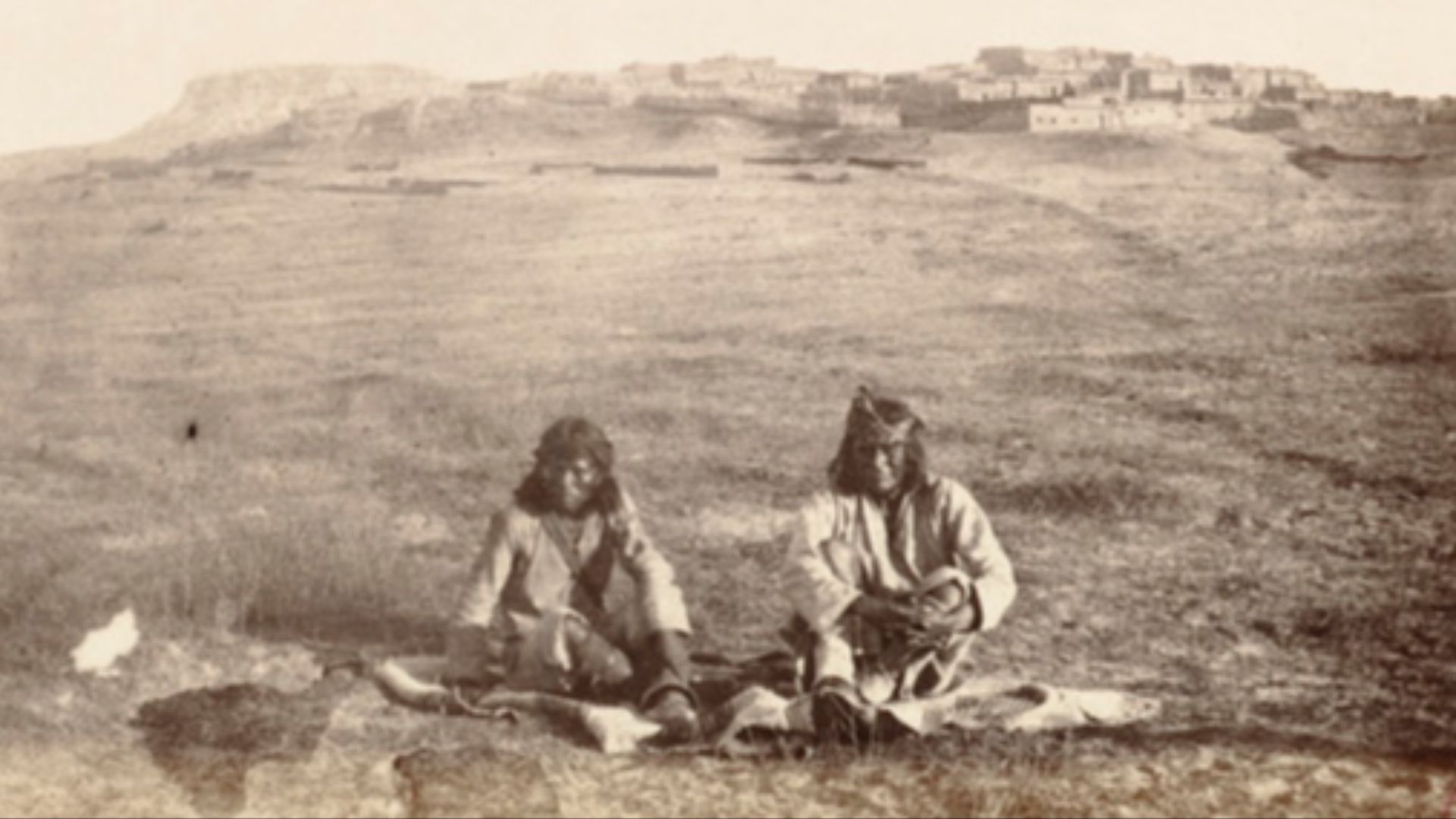

Gardner, Alexander, 1821-1882, Wikimedia Commons

Gardner, Alexander, 1821-1882, Wikimedia Commons

From Migration To Resistance

Long before the Pueblo Revolt, Ancestral Puebloans had already migrated from their original canyon homes to distant mesas, seeking refuge from warfare and environmental stress. This long history of adaptation and survival set the stage for 1680 when their descendants took the bold step of resisting colonial suppression.

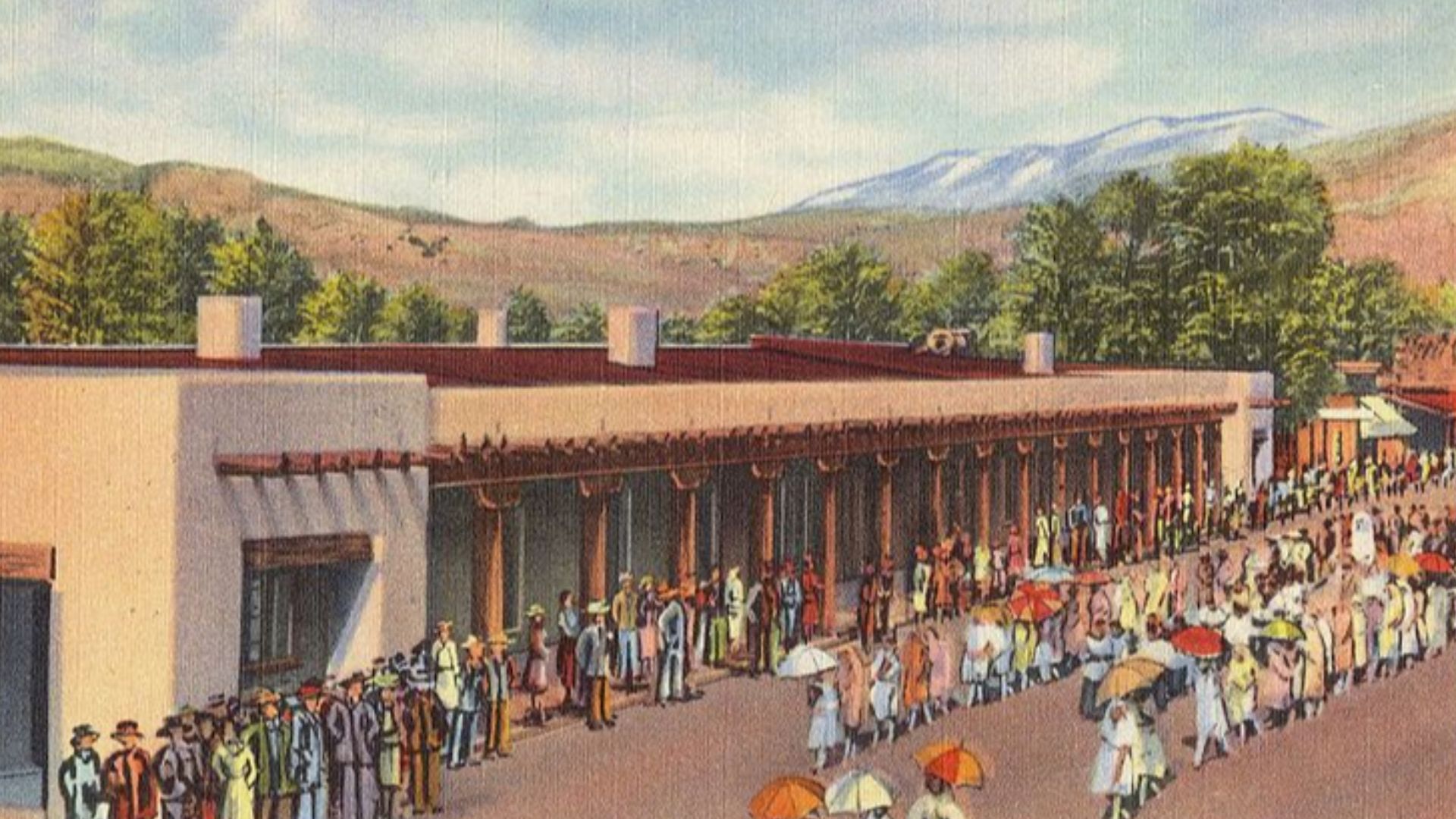

Loren Mozley for TRAP (USgov), 1936, Wikimedia Commons

Loren Mozley for TRAP (USgov), 1936, Wikimedia Commons

Spanish Oppression And Cultural Erasure

Imagine you’re minding your own business, and then someone wants to control you. Would you allow it? Well, for over a century, Pueblo communities endured violent Spanish incursions, which came with forced labor and religious persecution. Traditional practices were outlawed, rules changed, sacred items destroyed, and Catholic theocracies imposed.

Boston Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

Boston Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

The Resentment Grew Fast

The trauma of events like the Acoma Massacre fueled lasting resentment among the Pueblo people, and it deepened their determination to reclaim their ancestral identity and regain control of their lands and lives from the oppressive grip of Spanish colonial and religious domination.

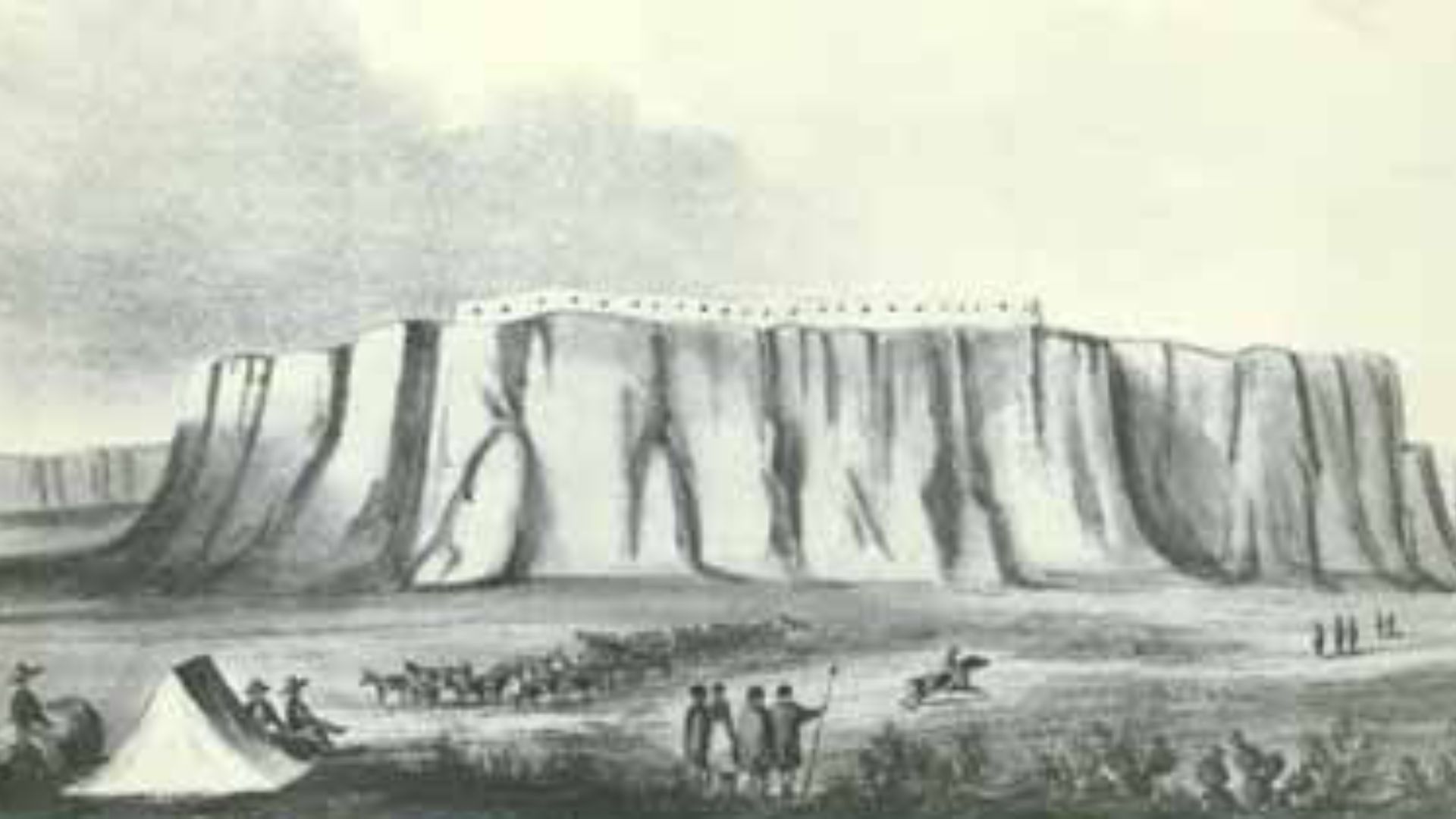

Graham, C.B., Wikimedia Commons

Graham, C.B., Wikimedia Commons

Pope And The Coordinated Uprising

In 1675, after being publicly punished by Spanish authorities, Tewa leader Pope began organizing a united resistance. Despite cultural and linguistic differences, over two dozen Pueblo communities joined forces. On August 10, 1680, they launched a coordinated uprising that killed 400 colonizers and expelled Spanish rule for twelve years.

The Architect of the Capitol, Wikimedia Commons

The Architect of the Capitol, Wikimedia Commons

Legacy Of The Revolt

The Pueblo Revolt remains one of the most successful Indigenous uprisings in North American history. Although the Spanish returned in 1692, the revolt led to a more tolerant approach to Pueblo customs. The event stands as a defining moment in Indigenous resilience and the enduring fight for cultural preservation.

Loren Mozley for TRAP (USgov), 1936, Wikimedia Commons

Loren Mozley for TRAP (USgov), 1936, Wikimedia Commons

Archaeological Consensus Gaps

While modern Pueblo people affirm continuity from Ancestral Puebloans, professional archeologists remain divided. Some support this view through artifact lineage and settlement mapping, but others await a broader consensus. Nonetheless, early scholars, such as Alfred V Kidder and J Walter Fewkes, documented oral histories that supported deliberate, structured southward migration.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

The Spirit That Still Walks With You

The Ancestral Puebloans may have moved on, but their spirit clings to the sandstone and sagebrush. You can hear it in the wind that sweeps through old dwellings and feel it in the sun that lights the kiva walls. Their story continues every time you wonder who came before you.

Wvbailey at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Wvbailey at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons