Archaeologists in southern Andalusia recently uncovered a massive stone tomb that dates back an astonishing 5,000 years. The structure, buried beneath layers of soil near the town of Teba, appears far more elaborate than most prehistoric graves found in the region. Early study shows that the people who built it invested significant effort in honoring their dead, leaving behind clues that hint at surprising connections beyond their community. As researchers examine the tomb’s layout and the objects discovered inside, a clearer picture of who these ancient people were—and how they interacted with the wider world—is beginning to emerge.

A Monumental Structure Hidden For Millennia

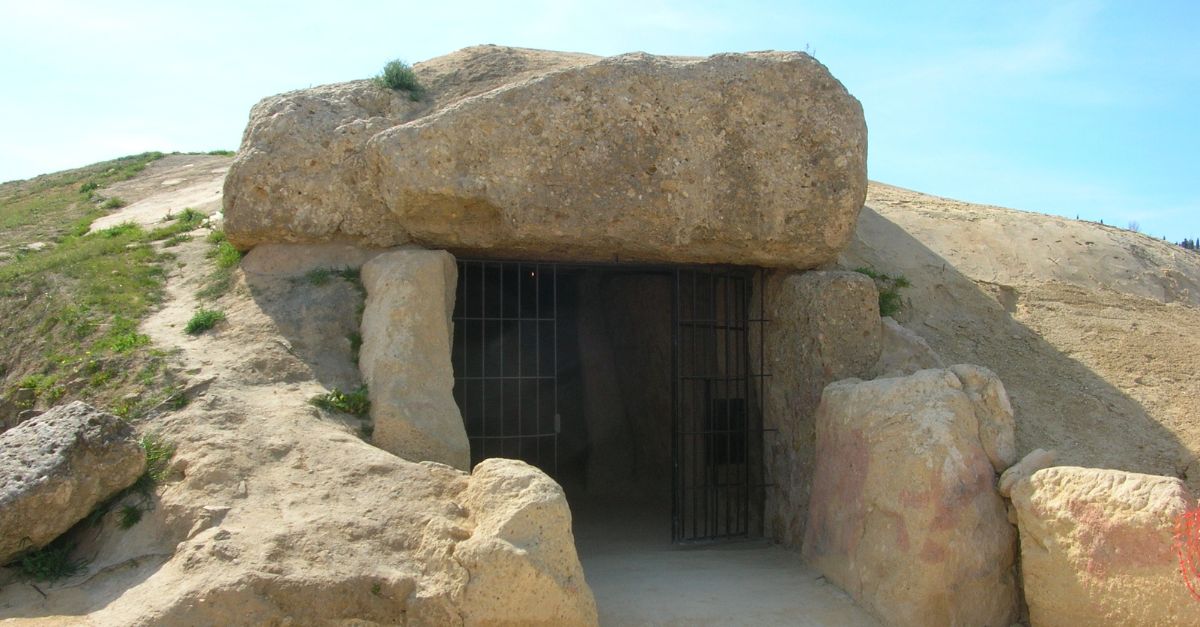

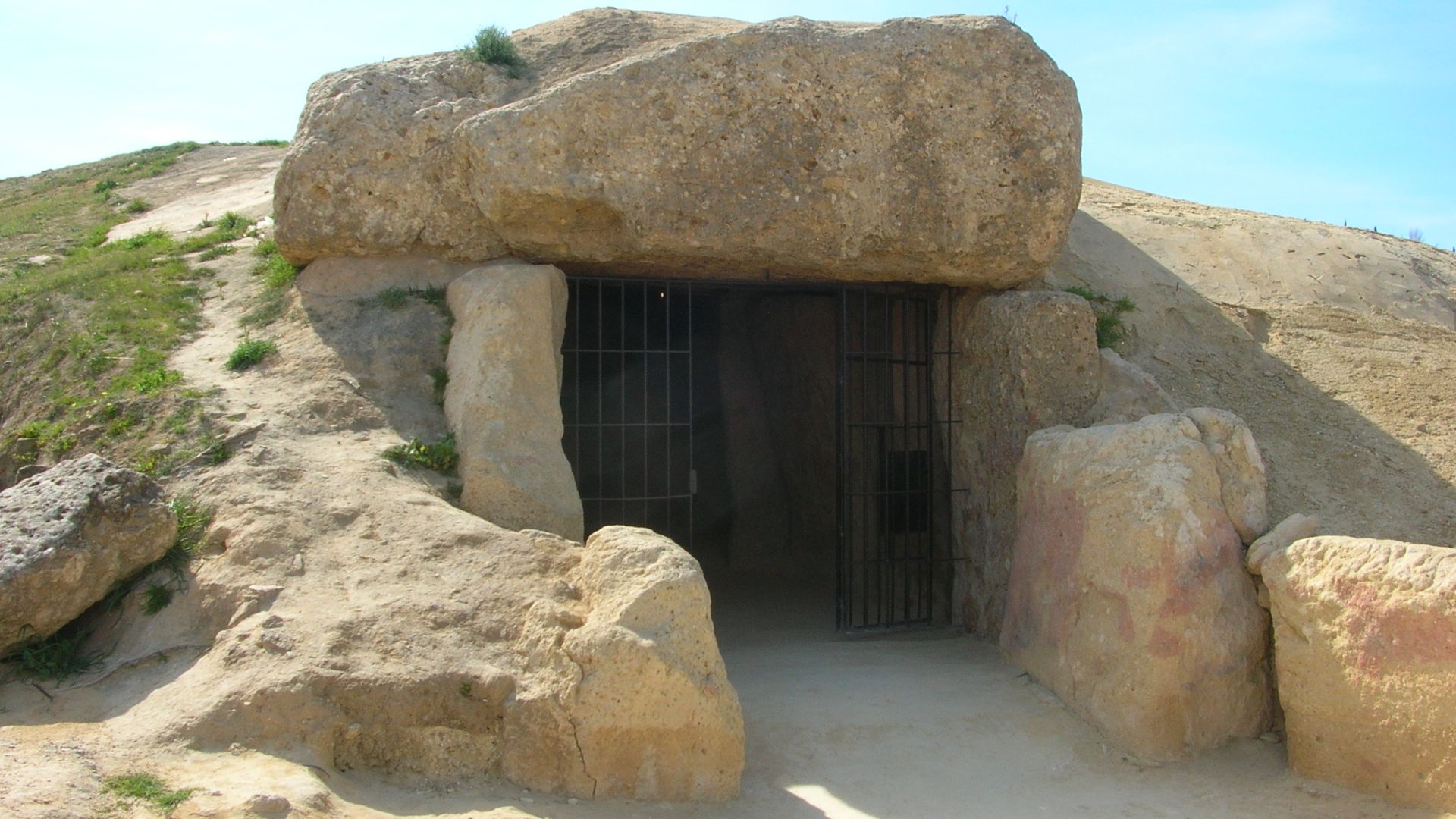

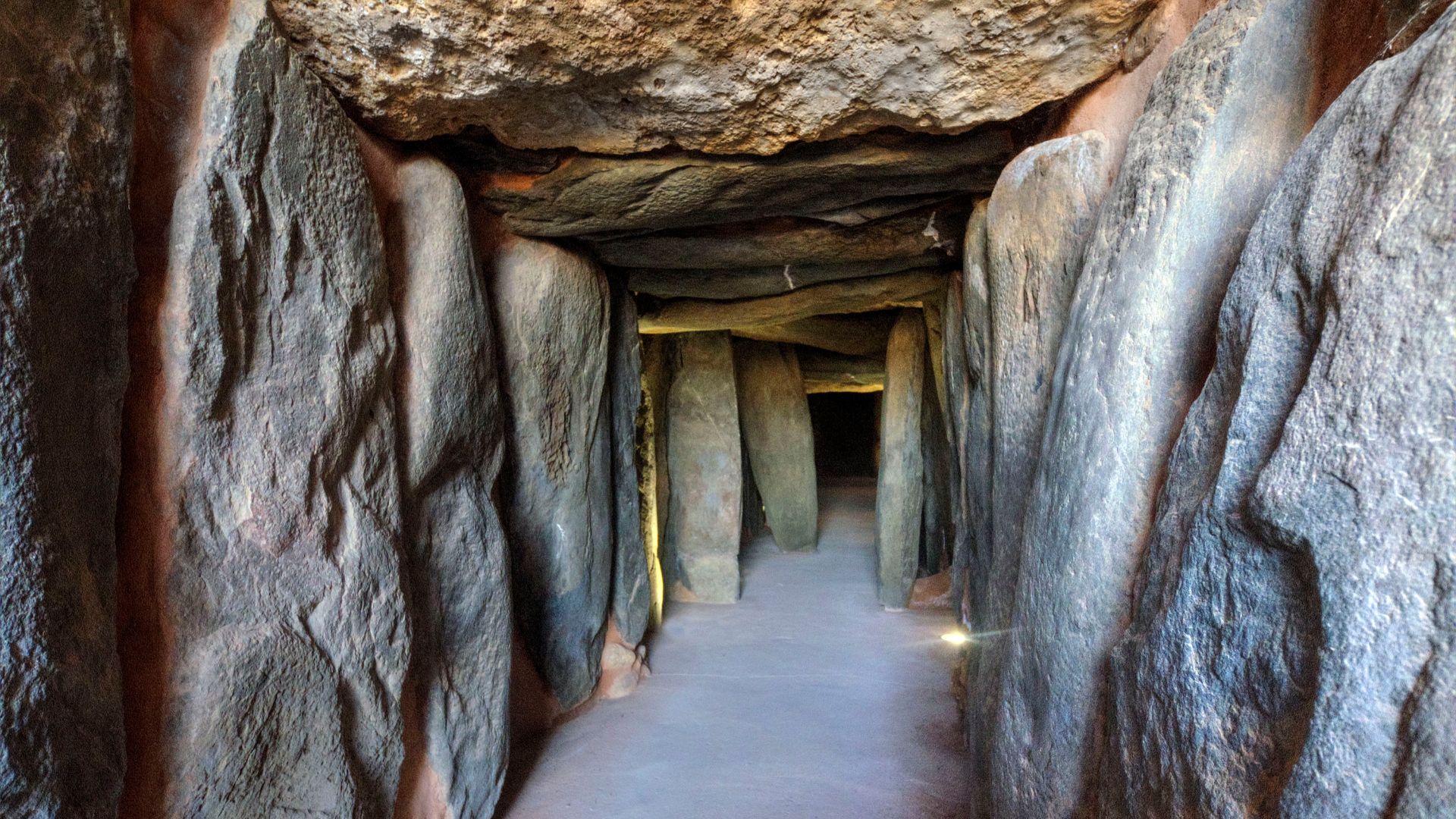

The Teba dolmen stands out because of its size, preservation, and complexity. The structure stretches about 13 meters from end to end and was originally covered by a tumulus, an earthen mound that helped protect the interior. Its builders placed upright stones called orthostats to form the walls, and they used large capstones to create a stable roof. Excavations revealed internal chambers and ossuaries, each used for placing human remains over multiple generations. This arrangement reflects a well-known tradition of collective burial practiced across Iberia during the late Neolithic and early Copper Age, when communities created long-lasting monuments to honor their dead.

Archaeologists found that the tomb likely served as a central gathering point for ritual activity, and the size of the monument suggests that the individuals buried there held importance within their community. The careful construction and reuse of the tomb show that people returned to this place repeatedly, maintaining continuity over time. Its excellent preservation helps researchers study construction techniques, burial organization, and long-term cultural practices with unusual clarity. Because many prehistoric structures in the region have been damaged by time or erosion, the Teba dolmen provides a rare and well-protected example of early engineering and community planning.

Angel M. Felicisimo from Merida, Espana, Wikimedia Commons

Angel M. Felicisimo from Merida, Espana, Wikimedia Commons

Exotic Grave Goods That Traveled Long Distances

Among the items recovered inside the tomb, archaeologists found flint arrowheads, large stone blades, and a halberd, all consistent with tools and weapons used during the Copper Age. Yet the most revealing discoveries were materials not native to inland Andalusia. Fragments of ivory, likely from elephant tusks, appear to have entered the region through early trade routes. Amber also appeared in the collection, a material associated with northern sources that spread through long-standing exchange networks. Seashells found inside the tomb offer additional evidence of contact with coastal communities, since the site lies far from the shoreline.

These findings confirm that early Iberian societies did not live in isolation. Instead, they participated in exchanges that moved goods of symbolic value over considerable distances. Such items were not only decorative; they carried social and ritual meaning. Their placement inside the tomb suggests that the people buried there, or the families who honored them, had access to materials that required established connections with other groups. Archaeologists view these goods as markers of identity and status. The presence of ivory, amber, and seashells strengthens the growing understanding that prehistoric Iberian communities formed wide networks that linked inland settlements with coastal regions and other parts of the peninsula.

What The Discovery Reveals About Early Iberian Life

The Teba dolmen gives researchers important clues about the structure and rituals of early Iberian communities. The monument shows that people organized themselves around shared burial rituals that helped maintain group identity. The presence of specialized stone tools, including finely crafted blades and a halberd, reflects both skilled workmanship and the activities central to daily life. These tools help researchers interpret broader patterns in farming, herding, and emerging metalworking. The careful placement of human remains inside the chambers suggests that the community viewed the tomb as a lasting space where memory and ritual merged.

As research continues, the dolmen’s architecture and grave goods will help refine the understanding of how early societies formed relationships beyond their local environment. The presence of imported materials confirms that travel and trade influenced cultural expression more than previously assumed. This discovery shows that communities living far from the coast still managed to access goods from distant sources, connecting them to a larger world. The Teba tomb stands as a well-preserved record of those interactions. It also serves as a reminder that long before modern trade, people built networks that shaped their beliefs, honored their dead with care, and linked inland and coastal worlds through shared traditions.