What The Middle Ages Left Behind

Despite popular opinions, the Middle Ages left behind objects that feel almost too extraordinary to be real. Some of their stuff even came covered in gold or carved to hold bones. But the best of the best are…

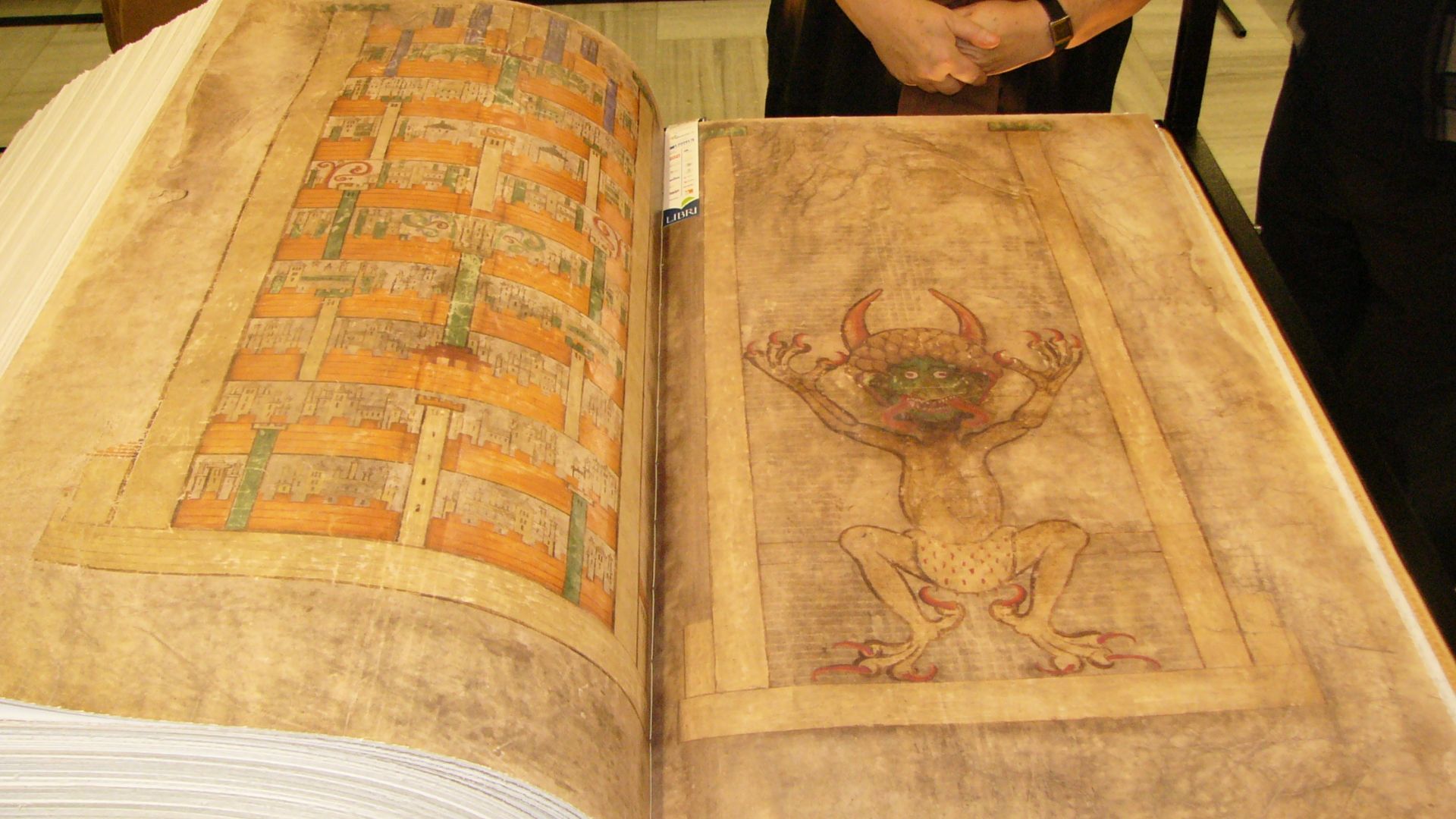

Codex Gigas (Devil’s Bible)

This 13th-century book is so massive it takes two people to lift it. It’s famous for a full-page drawing of the devil glaring from its parchment. Packed with medieval knowledge, myths say one monk wrote it in a single night with help from Satan.

Michal Manas, Wikimedia Commons

Michal Manas, Wikimedia Commons

Bayeux Tapestry

An embroidered strip nearly 230 feet long takes us back to 1066 and tells the story of the Norman Conquest of England. Scenes of battle, banquets, and preparation flow across linen panels. With so much action stitched in thread, it feels like a medieval storybook unfolding in fabric.

Staffordshire Hoard

In 2009, Terry Herbert found over 3,500 gold and garnet pieces buried in a field. The hoard had been underground for more than 1,000 years, and the items included select components of battle gear used by Anglo-Saxon warriors.

David Rowan, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

David Rowan, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Wikimedia Commons

Lewis Chessmen

Found on a beach in Scotland, these 12th-century walrus ivory chess pieces seem strangely human. One knight bites his shield, while others display brooding stares or sly grins. Experts believe they were made in Norway and were likely intended for use by a wealthy household.

Photograph © Andrew Dunn, Wikimedia Commons

Photograph © Andrew Dunn, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Jewel

It’s smaller than a matchbox, but it carried royal weight. Found in Somerset in 1693, the Alfred Jewel is made of gold, crystal, and enamel. A small inscription on it links it to King Alfred the Great, and scholars believe it guided fingers across sacred texts.

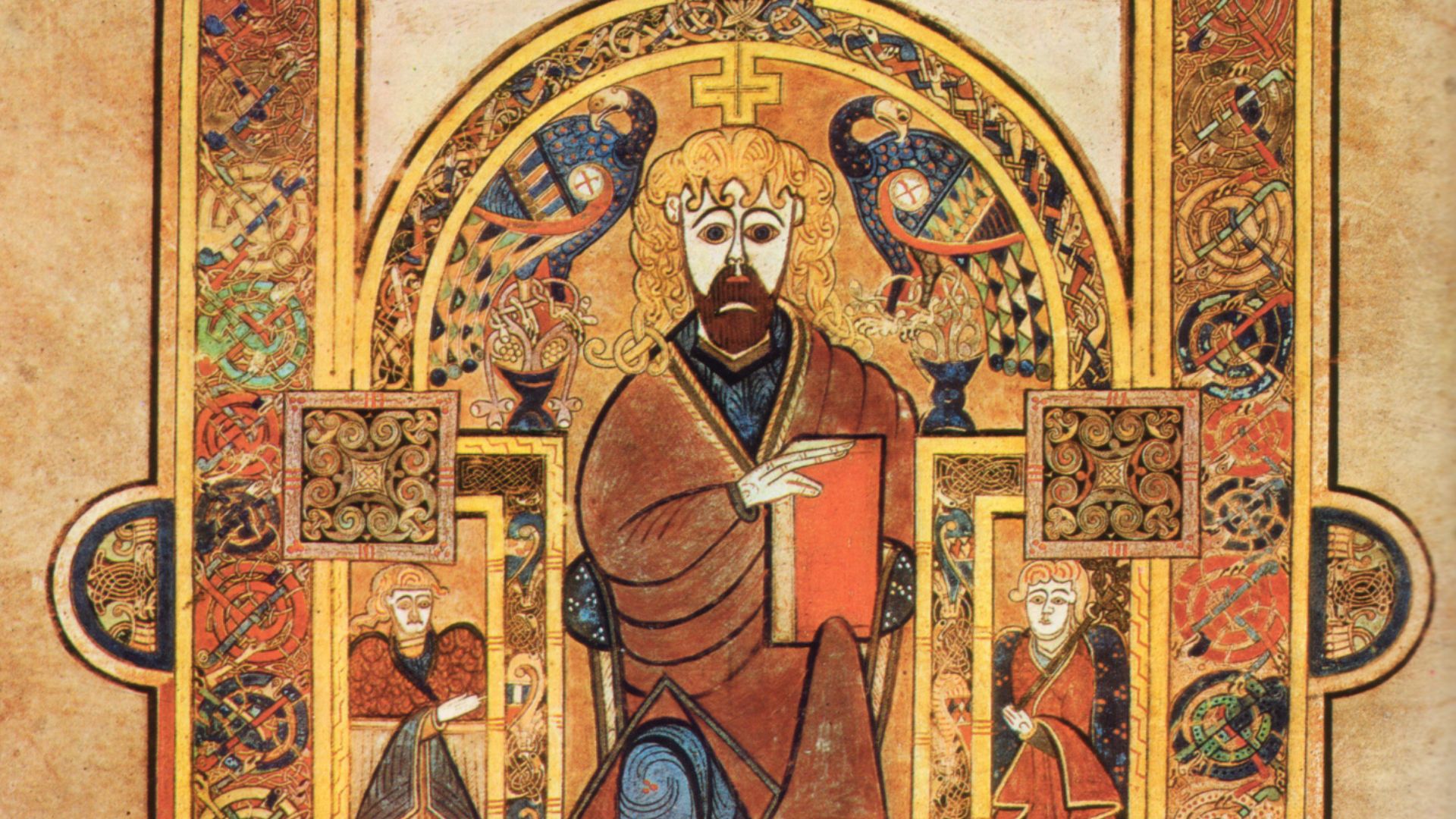

Book Of Kells

Created around 800 CE by monks in Scotland, the Book of Kells glows with swirling designs and jewel-bright colors. Every page of the Gospels bursts with detail. Even today, people still marvel at how artists achieved such dazzling beauty with natural pigments.

Unattributed, Wikimedia Commons

Unattributed, Wikimedia Commons

Westminster Retable

What once dazzled pilgrims now survives in fragments. Made in the 1200s for Westminster Abbey, this painted altarpiece was covered in gold and glass, and was hidden for centuries. Its restored pieces still hint at the splendor of royal worship that we nearly lost to time.

Unknown English painter, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown English painter, Wikimedia Commons

Otranto Cathedral Mosaic

The floor of this Italian cathedral is a storybook made of stone. Built in the 1100s, the Otranto mosaic includes biblical scenes, mythical beasts, and a tree connecting the stories. With thousands of pieces, it’s one of Europe’s largest surviving floor mosaics.

Holger Uwe Schmitt, Wikimedia Commons

Holger Uwe Schmitt, Wikimedia Commons

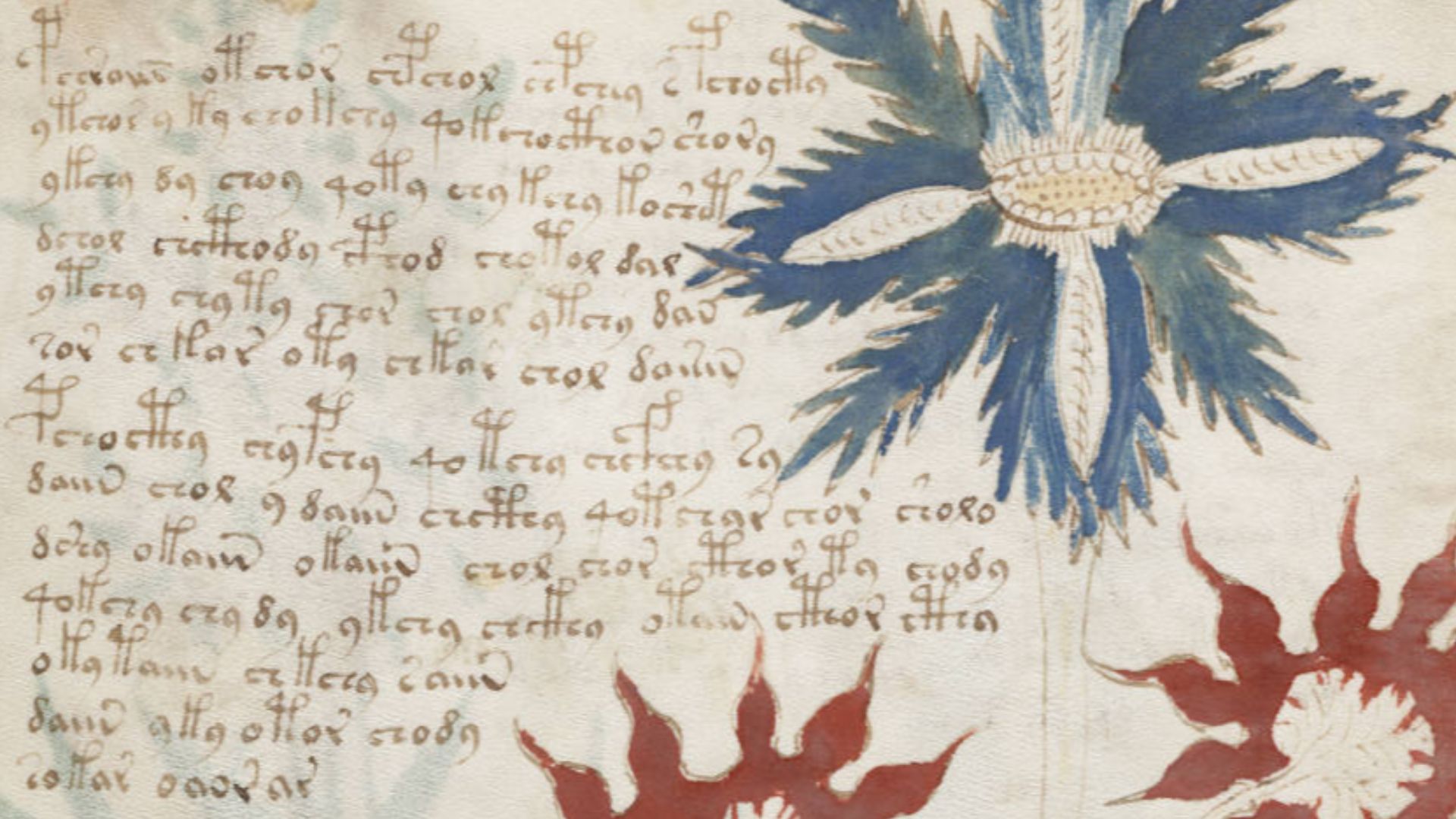

Voynich Manuscript

Its pages are packed with flowing script in no known language, surrounded by strange plants and odd human figures. Experts dated the manuscript to the early 1400s, and to date, no one can even read it. But that hasn’t stopped people from trying.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Sutton Hoo Helmet

This iron helmet was uncovered in a 7th-century ship burial in Suffolk, England. Decorated with bronze panels showing warriors and animals, it likely belonged to a powerful Anglo-Saxon leader. Only a few helmets from this period have survived in such detail.

Canterbury Cross

A metalworker in Anglo-Saxon England cast this small bronze cross more than 1,100 years ago. It carries intricate knotwork and traces of silver. When it was unearthed in Canterbury in 1867, the find later inspired interest in England’s early Christian art.

Storye book, Wikimedia Commons

Storye book, Wikimedia Commons

St Cuthbert’s Coffin Relics

When monks opened St Cuthbert’s wooden coffin centuries after his death, they found his body still intact. Alongside it were a comb, a cross, and one of the oldest gospel books in Europe. The coffin itself dates to the late 600s.

John Hamilton, Wikimedia Commons

John Hamilton, Wikimedia Commons

Durham Gospel Book

That tiny gospel inside St Cuthbert’s coffin is supposedly from 698. It’s the oldest known Western bookbinding—and one of the best-preserved books from the entire medieval world. You’ll notice how the red leather cover remained remarkably intact for over a thousand years.

Cloisters Cross

Carved from walrus ivory around 1150 CE, this monumental cross brims with miniature biblical scenes. Every inch teems with figures and inscriptions in a dense display of devotion merged with storytelling. Standing more than two feet tall, it is overwhelming with its sheer detail.

Holy Grail Of Valencia

Some believe this could be the real Holy Grail. The cup—made from agate—may date to the 1st century, but the base and handles were added during the Middle Ages. Today, it’s displayed in Valencia Cathedral and used during major religious ceremonies.

Vitold Muratov, Wikimedia Commons

Vitold Muratov, Wikimedia Commons

Aachen Throne Of Charlemagne

This stone throne didn’t sparkle, but it meant power. Historians believe that Charlemagne, king of the Franks and the first Holy Roman Emperor, ruled from Aachen and likely used this seat during his reign. Later emperors were crowned in it for centuries, continuing the tradition.

Berthold Werner, Wikimedia Commons

Berthold Werner, Wikimedia Commons

Cuerdale Hoard

A crumbling riverbank near Lancashire revealed this silver treasure in 1840. The Cuerdale Hoard included more than 8,000 Viking coins, bracelets, bars, and more. Experts think it was hidden around 905 CE—possibly by Norse exiles planning to retake Dublin from England.

multiple, unknown, Wikimedia Commons

multiple, unknown, Wikimedia Commons

Winchester Psalter “Hellmouth” Illustration

One of medieval art’s most terrifying images shows sinners being swallowed by a monster’s jaws. It appears in the Winchester Psalter, a 12th-century prayer book made for English royalty. The illustration warned readers about hell using vivid fear instead of gentle words.

from the Middle Ages, unknown, Wikimedia Commons

from the Middle Ages, unknown, Wikimedia Commons

Lindisfarne Gospels

On a remote English island, a single monk created this book by hand around 715 CE. The Lindisfarne Gospels combine Christian scripture with Celtic and Anglo-Saxon art. Its detailed pages and decorated letters remain a landmark of early medieval design and devotion.

Eadfrith of Lindisfarne (presumed), Wikimedia Commons

Eadfrith of Lindisfarne (presumed), Wikimedia Commons

Chalice Of Dona Urraca

This ornate chalice sits in Leon, Spain, and once belonged to a Castilian princess from the 11th century. Its cup is made of onyx, while the base holds pearls and gems. It has been housed in the Basilica of San Isidoro for centuries.

Locutus Borg (José-Manuel Benito Álvarez), Wikimedia Commons

Locutus Borg (José-Manuel Benito Álvarez), Wikimedia Commons

Pala d’Oro, St Mark’s, Venice

Few church decorations are this overwhelming. The Pala d’Oro—Italian for “Golden Cloth”—sits behind the altar in St Mark’s Basilica. Covered in gold and over 1,900 gems, it was built by Byzantine artists and expanded during the Crusades.

Dunstable Swan Jewel

A tiny white swan wearing a gold crown was once fastened to a noble’s clothing around 1400. This enamel badge came from England and showed loyalty to the House of Lancaster. The jewel was found near Dunstable and now rests in the British Museum.

Paul Hudson from United Kingdom, Wikimedia Commons

Paul Hudson from United Kingdom, Wikimedia Commons

Hunterian Psalter

Bright illustrations and bold colors fill this English prayer book from the 1100s. Its pages show angels, monsters, and scenes from scripture drawn with vivid detail. The book gets its name from William Hunter, a Scottish collector who donated it to a university.

AnonymousUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

AnonymousUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Coronation Mantle Of Roger II Of Sicily

The mantle was made in Palermo in 1133 or 1134, as recorded in its Arabic inscription. Lions and camels appear on the fabric, symbolizing power and conquest. Today, the mantle is displayed with the Imperial Regalia in Vienna.

MyName (Gryffindor) stitched by Marku1988, Wikimedia Commons

MyName (Gryffindor) stitched by Marku1988, Wikimedia Commons

Gloucester Candlestick

At first glance, it looks like metal vines tangled into a knot. The Gloucester Candlestick was crafted around 1110 CE and is filled with figures battling temptation. Designed for church use, it shows how medieval artists told spiritual stories through objects.

Unknown artistUnknown artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown artistUnknown artist, Wikimedia Commons