Hart Island

Hart Island holds the remains of over a million souls—unclaimed, unnamed, and largely forgotten. For more than a century, this potter’s field has been a quiet resting place for the city’s most vulnerable, from convicts and the homeless to victims of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Known for its mass graves and haunting history, the island now stands on the edge of a new chapter.

Location

Hart Island is located at the western end of Long Island Sound, in the northeastern Bronx in New York City. It is part of the Pelham Islands archipelago and is east of City Island.

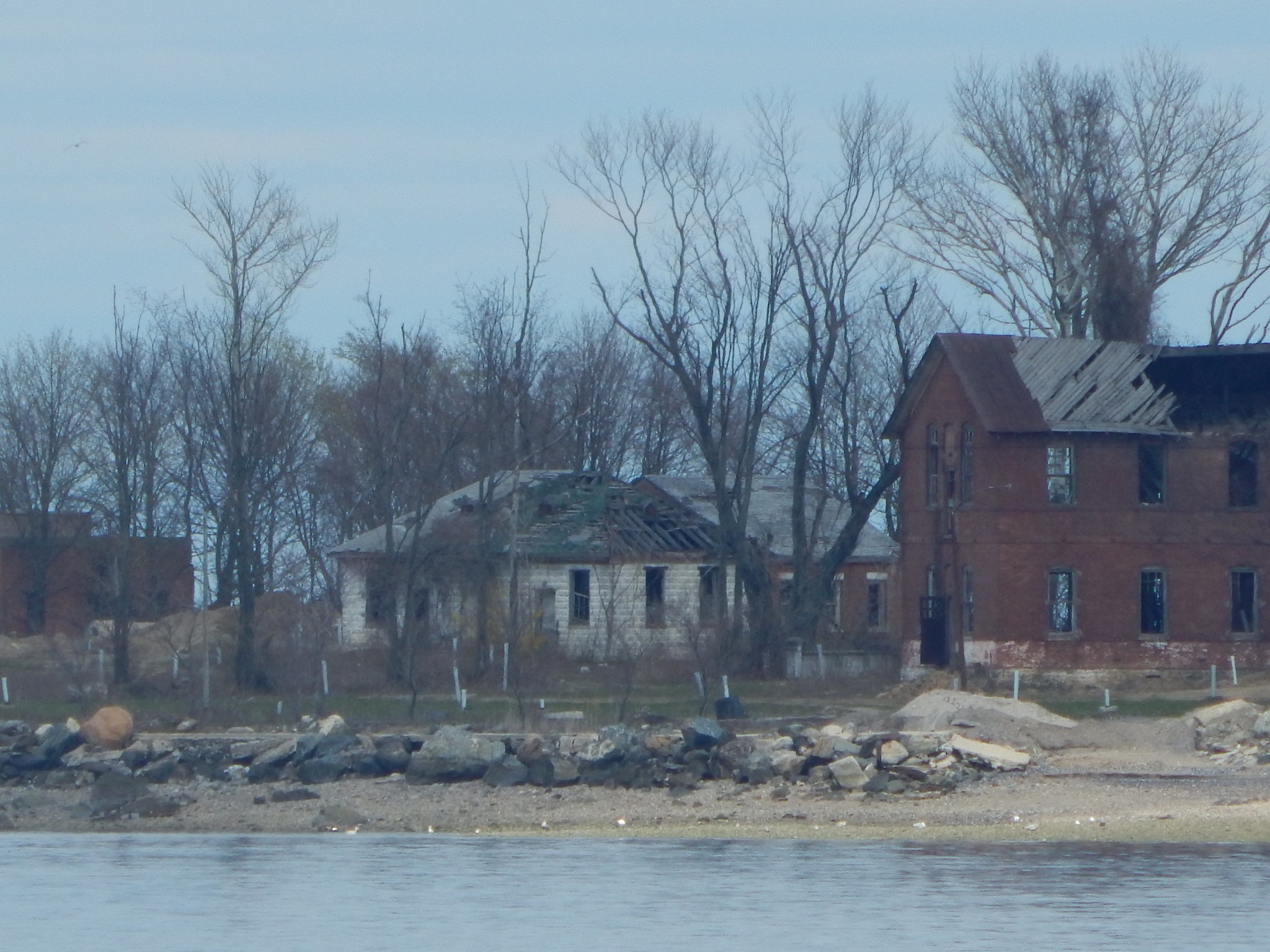

Doc Searls, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Doc Searls, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Geography

The small island measures approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) long by 0.33 miles (0.53 km) wide at its widest point. It is isolated from the rest of the city: there is no electricity and it can only be accessed by ferry.

Bjoertvedt, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bjoertvedt, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

History

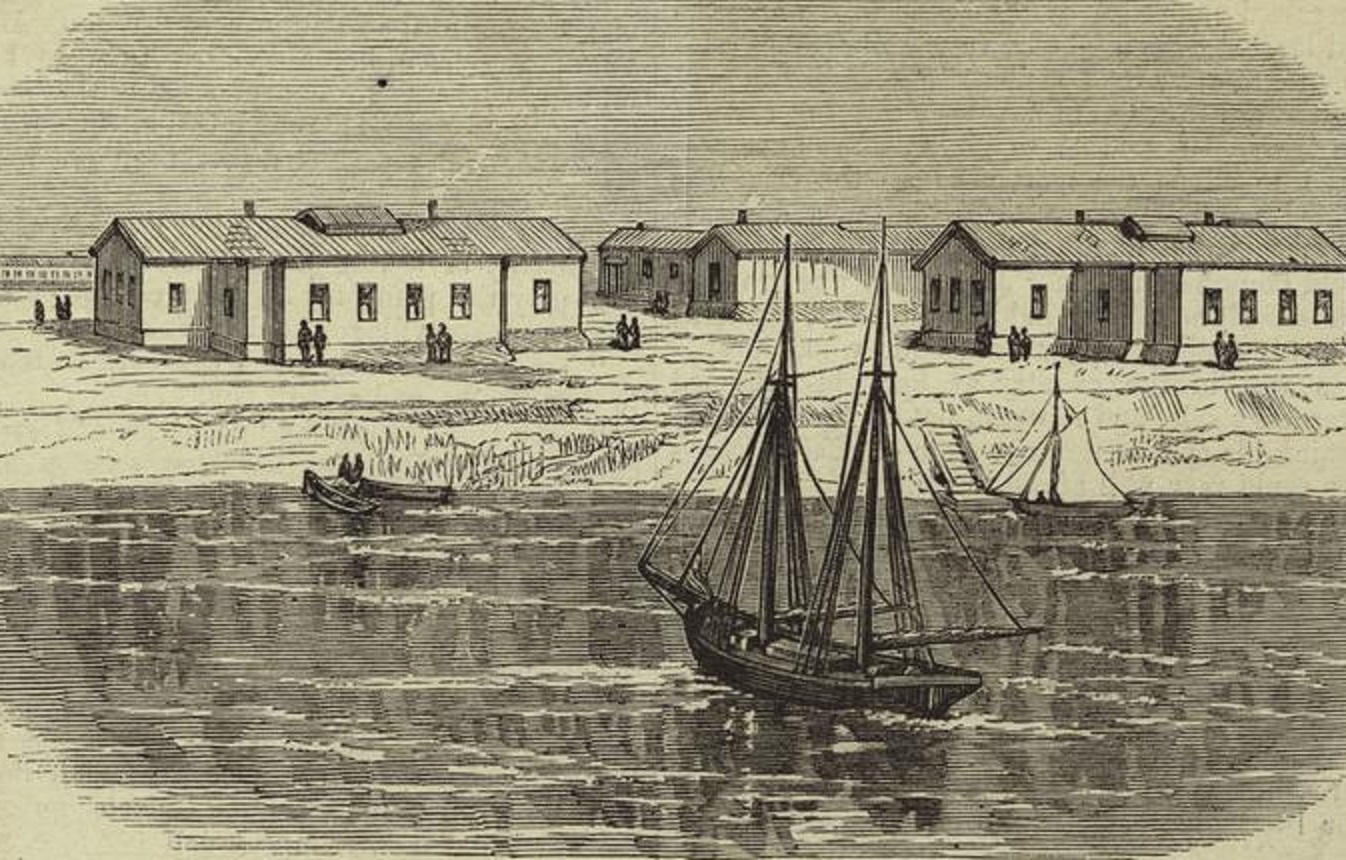

Before it became a public burial site, Hart Island had many previous uses. It was originally home to the Siwanoy tribe of Native Americans.

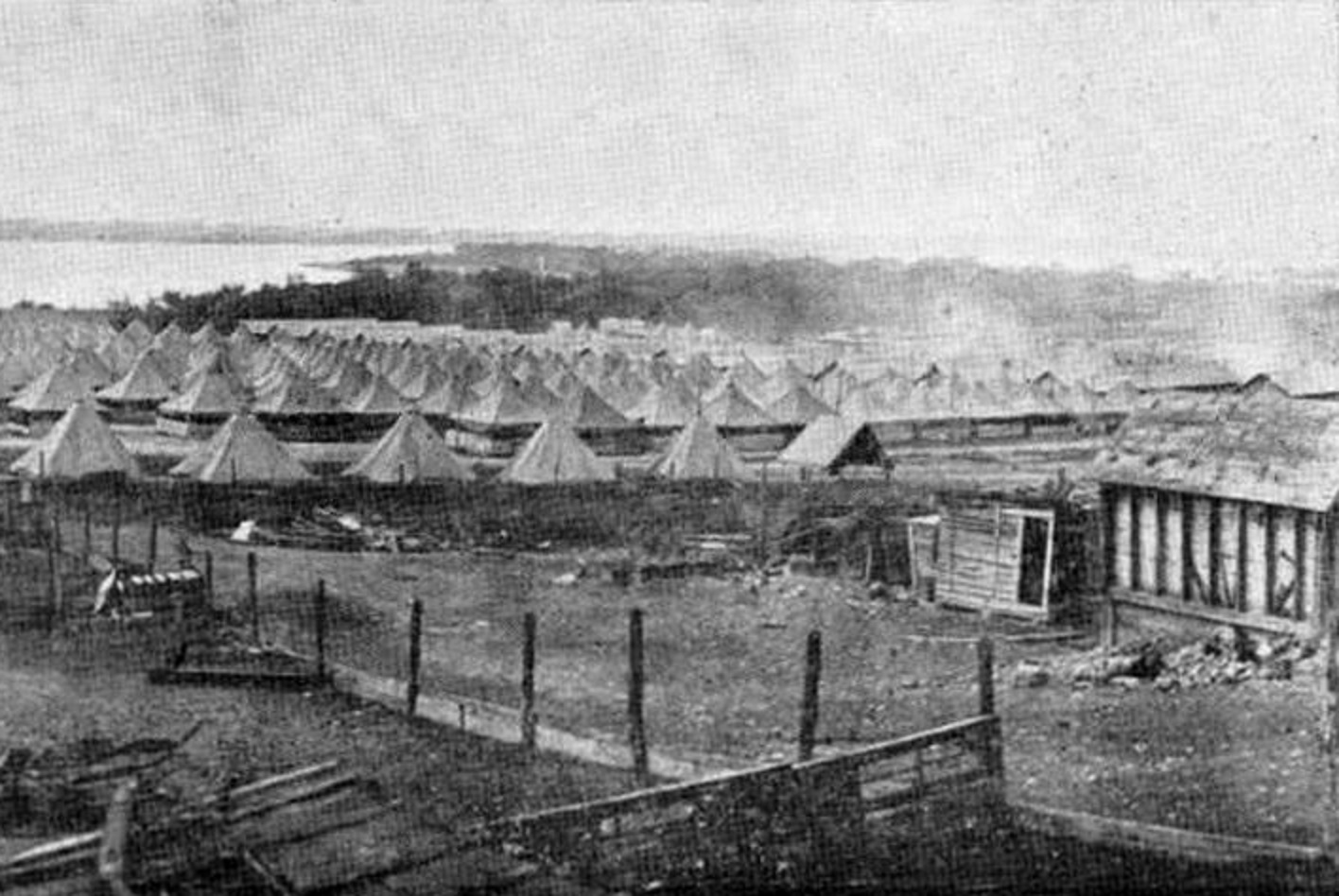

It later served as a military training site, a POW camp, a quarantine station, a psychiatric hospital site, an industrial school site, a workhouse site, a prison, and so much more.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Island of Exile

For much of its history, Hart Island has served as a burial ground for those society cast aside—whether troubled, impoverished, or infectious. It became a quiet, somber dumping ground for the unwanted, where the forgotten were laid to rest far from the city they once called home.

Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, Picryl

Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, Picryl

The First of the Burials

The first burials are said to have taken place way back in 1869, when the island was used as a public cemetery for poor people, or for people whose bodies were unclaimed after their demise.

This also included a lot of veterans.

Gravediggers

Before civilian contractors were hired in 2020, the gravediggers were inmates from the nearby Rikers Island jail. They were paid fifty cents an hour to bury bodies on the island.

Disease-ridden Bodies

In 1985, only a few years after AIDS was discovered in the U.S., the island became the final resting place for anyone who passed from the AIDS-related illness.

Fear of Contagion

In that year alone, sixteen people who died from AIDS were buried in isolated, deep graves at the remote southern tip of Hart Island. At the time, fear and misinformation led many to believe their remains could still spread the disease—even in death, stigma kept them at a distance.

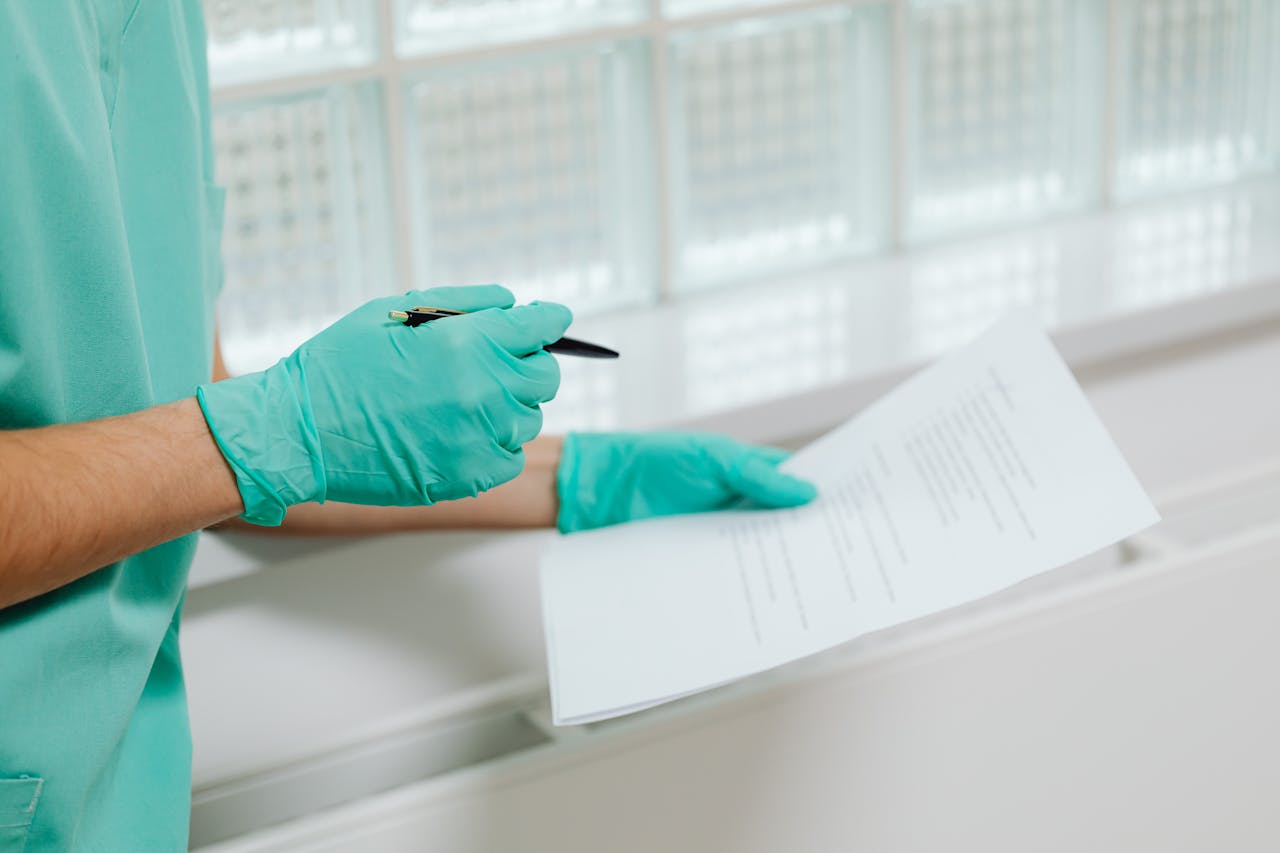

Burial of Disease-ridden Bodies

During the growing AIDS epidemic, diseased bodies were delivered in body bags and buried by inmates wearing protective jumpsuits.

When it was finally learned that the bodies could not spread HIV, the city started burying them in mass graves like the others.

The First Child

Hart Island is also the final resting place for the first child to pass in New York City of AIDS-related illness. The little one’s grave is marked as “SC (special child) B1 (Baby 1) 1985.”

Since then, thousands of people who have died of AIDS have been buried on Hart Island, but the precise number is unknown.

No More Residential Facilities

In 1991, the city ended all other uses of the island except as a public cemetery. The cemetery was allotted 131-acres.

At this point, the cemetery was provided mostly for diseased bodies, and bodies of unclaimed people.

Reputation

Hart Island is often called the largest tax-funded cemetery in the United States—and the largest of its kind anywhere in the world. It’s also considered one of the biggest mass graves in the country, a haunting reminder of those buried not with ceremony, but necessity.

The Burials: Trenches

Most of the bodies were buried in trenches, piled on top of each other. Diseased bodies were buried separately, or on remote parts of the island.

Eventually, basic wooden coffins were introduced.

The Burials: Babies

Babies are placed in coffins, which are stacked in groups of 100, measuring five coffins deep and usually in twenty rows.

The Burials: Adults

Adults are placed in larger pine boxes placed according to size, and are stacked in sections of 150, measuring three coffins deep in two rows and laid out in a grid system.

Coffin Specifics

There are seven coffin sizes used on Hart Island, ranging from just 1 to 7 feet in length. Each plain box is marked with an ID number, along with the person's age, ethnicity, and, when known, the location where their body was discovered—a quiet record of lives lost and stories untold.

Claiming Bodies

Bodies of adults are often dug up when families are able to locate their relative’s bodies through DNA, photographs and fingerprints that are kept on file.

This is most common after pandemics when bodies are buried quickly and unclaimed until a later date.

The U.S. National Archives, Picryl

The U.S. National Archives, Picryl

Unearthed Bodies

There was an average of 72 bodies being dug up and claimed per year from 2007 to 2009. As a result, the adults' coffins were staggered to speed up removal.

It was rare for children’s bodies to be unearthed.

The U.S. National Archives, Picryl

The U.S. National Archives, Picryl

Baby Burials

About half of the burials on Hart Island are of children under five, who passed in hospitals. These babies were identified prior to burial as the mothers signed papers authorizing a “City burial”.

Usually, the mothers were unaware of what that meant and didn’t realize their babies’ bodies were being buried in a mass public grave.

Unclaimed Bodies

A significant number of those buried on Hart Island are people whose families live overseas. Many of these families search tirelessly for answers, hoping to locate the final resting place of a loved one.

But the search is often difficult—Hart Island’s burial records have long been managed within the prison system, making access limited and navigation frustratingly complex.

Amputated Body Parts

Hart’s Island is also used to dispose of amputated body parts, which are placed in boxes labeled "limbs". These typically include body parts that do not have a body to match them with.

Global Environment Facility, Flickr

Global Environment Facility, Flickr

Regulations

Regulations specify that the coffins generally must remain untouched for 25 years, except in cases of unearthing.

After the 25 years though, the graves can be used again.

State Archives of North Carolina, Picryl

State Archives of North Carolina, Picryl

Reusing Burial Trenches

In the past, burial trenches were re-used after 25–50 years, allowing for sufficient decomposition of the remains.

Since then, however, historic buildings have been demolished to make room for new burials.

The Flu Pandemic

In 2008, during a severe flu pandemic, Hart Island was designated as the site for mass burials. A massive trench was prepared, capable of holding up to 20,000 bodies—a stark reminder of the island’s long-standing role in the city’s response to public health crises.

Covid-19 Pandemic

In 2020, Hart Island was once again the designated site for mass burials during the Covid-19 pandemic. It was initially set up as a “just in case” burial site if mortuaries were to become overwhelmed.

However, this happened quicker than expected.

Covid-19 Pandemic Burials

Preparations for mass graves began as early as the end of March 2020, not long after the Pandemic started.

Losses at home were increasing significantly, though the corpses were not tested for the virus.

Private Contractors

At this time, private contractors were hired to replace inmates, as the death toll was rapidly rising by the day, and fear of contagion was present once again.

Covid-19: Unclaimed Bodies

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of unclaimed bodies surged. In 2020 alone, it’s estimated that nearly 3,000 individuals were buried on Hart Island—one of the highest burial counts in its recent history.

Kuncoro Widyo Rumpoko, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Kuncoro Widyo Rumpoko, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Time Sensitive Matter

During the pandemic, NYC was inundated with bodies—not just from the virus.

Any bodies that were not immediately claimed were sent to Hart Island in their cheap wooden coffins, and buried on top of each other in the newly dug mass graves.

This was the only option as bodies were piling up quicker than the mortuaries could receive them.

Bodies Claimed in 2020

The mass graves were dug strategically to allow for easy exhumation, as the city recognized that not enough time was given for bodies to be claimed.

However, since 2020, only 32 bodies from Hart Island were claimed by loved ones.

Total Bodies Buried on Hart Island

Currently, the estimated total of bodies buried on Hart Island, since its beginning, is well over one million.

Even after the covid-19 pandemic has quieted, the island continues to bury unclaimed bodies. But that’s not its only purpose anymore.

Hart Island’s New Plan

For decades, the burials on Hart Island remained largely hidden from public view—a quiet secret few spoke about. But the COVID-19 pandemic brought the island into the spotlight, revealing its somber role in the city’s history. Now, what was once New York’s most forbidden place is being reimagined as a space for public access and remembrance.

Audley C Bullock, Shutterstock

Audley C Bullock, Shutterstock

Hart Island’s Guided Tours

In 2023, NYC Parks' Urban Park Rangers started offering free walking tours of the island twice per month.

Registration is required through an online form and participants will be selected by lottery.

Gravesite Visits

For people who wish to visit the final resting place of a loved one, the City offers private gravesite visits to Hart Island twice a month, on weekends.

Finding Loved Ones on Hart Island

Hart Island records are searchable through the Hart Island database, which allows the public to determine if a loved one is buried on the island.

Records previous to 1977 may not be found.

Burial Records

If someone was buried at Hart Island, their death certificate will say "City Burial" or "Hart Island" in the burial information.

Removing Remains from Hart Island

If a family confirms their loved one is buried on Hart Island and wants to move the remains elsewhere, they can work with a licensed funeral home to request a disinterment.

There’s no fee for this service, but it depends on whether the remains can be located and recovered without difficulty.

Final Thoughts

Hart Island, New York City’s potter’s field, is currently the burial site for millions of bodies—and counting—most of which are in unmarked mass graves.

Although it had numerous intriguing uses over the years, the island’s disposal of the unclaimed deceased remains its most well-known purpose.